Aesthetic Appeal vs. Inventive Step: Japan's Supreme Court Clarifies Design Protection Standards in the Flexible Hose Case

Judgment Date: March 19, 1974

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Case Number: Showa 45 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 45 (Action for Rescission of a Trial Decision)

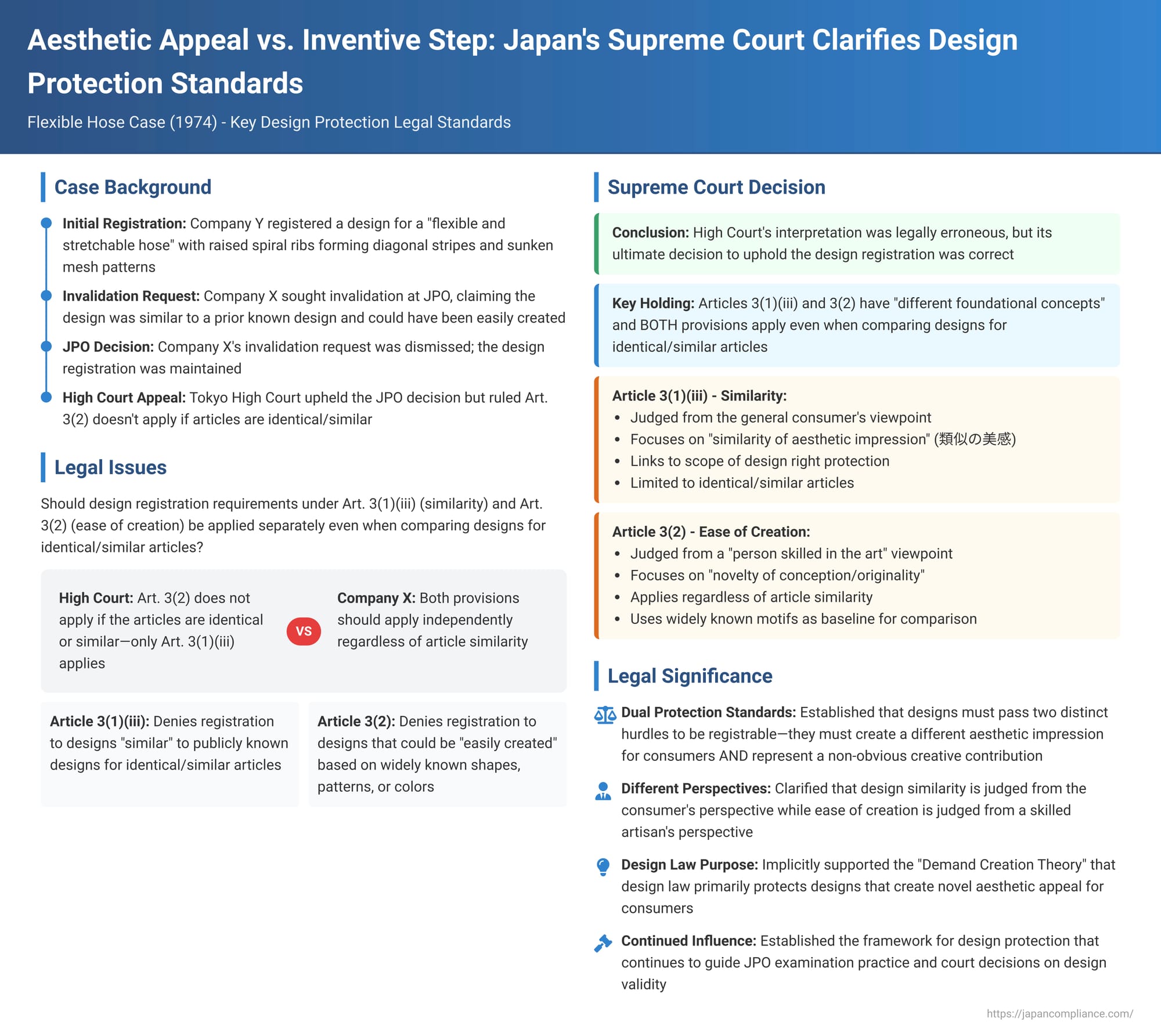

The "Flexible Hose case" (可撓伸縮ホース事件 - Katō Shinshuku Hōsu Jiken), decided by the Japanese Supreme Court in 1974, is a foundational judgment that meticulously delineated the distinct criteria for assessing the registrability of industrial designs under Japanese Design Law. The Court clarified the relationship between Article 3, Paragraph 1, Item 3 (which denies registration to designs "similar" to publicly known designs for identical or similar articles) and Article 3, Paragraph 2 (which denies registration to designs that could have been "easily created" by a person skilled in the art based on widely known shapes, patterns, or colors). This decision established that these are two independent hurdles, each with its own perspective and purpose, even when the articles in question are the same.

The Design in Question: A Flexible Hose and an Invalidation Challenge

The case centered on a registered industrial design owned by Company Y (the appellee before the Supreme Court). The article to which this design pertained was a "flexible and stretchable hose" (the "Registered Design").

Company X (the appellant before the Supreme Court) sought to invalidate Company Y's Registered Design. Company X filed an invalidation trial with the Japan Patent Office (JPO), arguing primarily on two grounds:

- Similarity to a Prior Design (Article 3(1)(iii)): Company X alleged that the Registered Design was similar to a previously known design (the "Cited Design") for the same type of article, and therefore should not have been registered under Article 3, Paragraph 1, Item 3 of the Design Law.

- Ease of Creation (Article 3(2)): Company X also contended that the Registered Design could have been easily created by a person skilled in the art based on the Cited Design and other publicly known design elements, making it unregistrable under Article 3, Paragraph 2 of the Design Law.

The JPO dismissed Company X's invalidation request. Company X then appealed this JPO decision by filing a lawsuit with the Tokyo High Court, seeking the cancellation of the JPO's trial decision.

The Lower Court's Interpretation: A Single Test for Same-Article Designs?

The Tokyo High Court also ruled against Company X, upholding the validity of the Registered Design.

- Regarding the similarity claim under Article 3(1)(iii), the High Court found that the Registered Design produced a "completely different design effect" (意匠的効果 - ishōteki kōka) compared to the Cited Design and, therefore, could not be considered a similar design.

- Regarding the ease of creation claim under Article 3(2), the High Court adopted a restrictive interpretation. It reasoned that Article 3, Paragraph 1 (which includes item iii) deals with the creativity of designs in relation to prior known designs for identical or similar articles. In contrast, it viewed Article 3, Paragraph 2 as addressing designs lacking creativity in relation to widely known shapes, patterns, etc., embodied in articles other than those identical or similar to the one in question. Therefore, the High Court concluded that when the articles of the compared designs are identical or similar (as was the case here, both being flexible hoses), the assessment of registrability requirements (specifically creativity-related aspects) should be conducted exclusively under Article 3, Paragraph 1. According to this view, Article 3, Paragraph 2 would have no application if the articles were the same or similar.

Dissatisfied with this reasoning, particularly the non-application of Article 3(2), Company X appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Two-Track Analysis: Distinguishing Similarity and Ease of Creation

The Supreme Court ultimately dismissed Company X's appeal, meaning the Registered Design remained valid. However, while it affirmed the High Court's conclusion on the specific facts, it significantly corrected the High Court's legal interpretation regarding the applicability of Article 3, Paragraph 2.

1. On Design Similarity (Article 3(1)(iii))

The Supreme Court briefly affirmed the High Court's finding that the Registered Design was not similar to the Cited Design, stating that this determination was " justifiable and can be upheld." It did not delve into a detailed re-evaluation of the aesthetic comparison on this point.

2. On Ease of Creation (Article 3(2)) – The Core Clarification

This was where the Supreme Court provided its most significant pronouncements:

- Interpretation of Article 3(1) (Novelty and Similarity): The Court first explained that for a design to be refused registration under Article 3, Paragraph 1 (due to identity or similarity with a design publicly known, or described in a distributed publication, before the application), two conditions must generally be met:

- The article to which the applied-for design pertains must be identical or similar to the article of the prior known design.

- The design itself (the aesthetic creation) must also be found to be identical or similar.

- Interpretation of Article 3(2) (Ease of Creation / Non-Obviousness): The Court then sharply contrasted this with Article 3, Paragraph 2. It stated that Article 3(2) operates from a different perspective than Article 3(1). While Article 3(1) deals with the identity or similarity of designs as embodied in specific articles, Article 3(2) sets a standard based on abstract motifs – specifically, shapes, patterns, colors, or their combinations that were "widely known in Japan" (公然知られた形状、模様若しくは色彩又はこれらの結合 - kōzen shirareta keijō, moyō wしくは shikisai matawa korera no ketsugō) before the application. The registrability requirement under Article 3(2) is that the applied-for design could not have been "easily created" by a "person skilled in the art" (当業者 - tōgyōsha) based on such widely known motifs. Crucially, the Court emphasized that for the purpose of Article 3(2), the "identity or similarity of the articles to which these motifs are attached is not an issue at all."

- Fundamental Distinction Between Article 3(1)(iii) and Article 3(2): The Supreme Court further elaborated on this distinction:

- Article 3(1)(iii) (Similarity): This provision is linked to the scope of a design right. Under Article 23 of the Design Law, the effect of a design right extends not only to the registered design itself but also to designs that are "similar" to it. A similar design, in this context, is one that, when applied to an article identical or similar to that of the registered design, evokes a similar aesthetic impression (類似の美感 - ruiji no bikan) in the general consumer. Thus, Article 3(1)(iii), in determining unregistrability due to similarity to a prior known design, is concerned with the similarity of aesthetic impression from the viewpoint of the general consumer, specifically for designs pertaining to identical or similar articles.

- Article 3(2) (Ease of Creation): This provision, by contrast, removes the restriction of identical or similar articles. It addresses the novelty of conception or the originality of the design from the viewpoint of a person skilled in the art (a pertinent artisan), using socially widely known motifs as the baseline for comparison.

- The Court concluded that these two provisions have "different foundational concepts" (考え方の基礎を異にする規定 - kangaekata no kiso o kotonisuru kitei).

- Error in the High Court's Reasoning: Based on this distinction, the Supreme Court found that the Tokyo High Court's assertion—that Article 3(2) is inapplicable if the designs in question pertain to identical or similar articles—was an error in the interpretation of Article 3. The Supreme Court clarified that even for designs on identical or similar articles, the assessment of "similarity of aesthetic effect" under Article 3(1)(iii) and the assessment of "ease of creation" under Article 3(2) are not necessarily congruent. A design might be deemed dissimilar under Article 3(1)(iii) (because it creates a different overall aesthetic impression for the consumer) but could still be found to have been easily creatable under Article 3(2) by a skilled artisan. (The Court noted a proviso in Art. 3(2) that if a design is easily creatable from a prior design that is covered by Art. 3(1)(i), (ii) or (iii), then only Art. 3(1) applies, effectively meaning that if it's similar to a prior art design under Art. 3(1)(iii) and easily creatable from it, Art. 3(1)(iii) is the primary ground for refusal.)

Application of Corrected Law to the Flexible Hose Design Facts:

Despite finding a legal error in the High Court's reasoning about the applicability of Article 3(2), the Supreme Court ultimately upheld the High Court's decision to dismiss Company X's invalidation claim. The Supreme Court referred to the High Court's factual findings, which described the Registered Design as having raised spiral ribs forming prominent plain diagonal stripes, with the areas between these ribs featuring a sunken mesh pattern also forming diagonal stripes. The High Court had found that this combination of contrasting elements, repeated along the length of the hose, created a distinct aesthetic effect for the viewer, quite different from the Cited Design and other conventional flexible hoses. Based on these affirmed factual findings about its unique appearance and aesthetic effect, the Supreme Court concluded that the Registered Design possessed originality in its conception and could not be said to have been easily created by a person skilled in the art from the Cited Design or other widely known shapes, patterns, or colors. Thus, the Registered Design did not fall foul of Article 3(2) either.

The Purpose of Design Law: Creation, Confusion, or Demand Stimulation?

The Supreme Court's distinction between the consumer's viewpoint for assessing "similarity" under Article 3(1)(iii) and the skilled artisan's viewpoint for "ease of creation" under Article 3(2) sheds light on the underlying objectives of Japanese Design Law. Three main theories:

- Creation Theory (創作説 - sōsaku setsu): Posits that design law primarily aims to protect the creativity inherent in the design. Under this theory, "similarity" in Article 3(1)(iii) would also likely be judged from a skilled artisan's perspective, focusing on creative differences, much like Article 3(2). The High Court in the Flexible Hose case appeared to adopt this view.

- Confusion Theory (混同説 - kondō setsu): Argues that the main purpose is to prevent consumer confusion between articles due to similar designs, thereby maintaining orderly trade. "Similarity" here would be judged based on whether consumers are likely to confuse the articles themselves.

- Demand Creation Theory (需要説 - juyō setsu): Suggests that design law protects a design's function of attracting consumers and stimulating demand, thereby contributing to industrial development. "Similarity" under this theory would be assessed by whether the new design offers a novel aesthetic appeal to consumers compared to prior designs.

The Supreme Court, by differentiating the consumer's perspective (for aesthetic similarity) from the skilled artisan's perspective (for inventive step/originality), clearly rejected a purely "Creation Theory" approach for Article 3(1)(iii). While the judgment did not explicitly endorse either the "Confusion Theory" or the "Demand Creation Theory," its emphasis on "aesthetic impression" for the "general consumer," without specific mention of product confusion, makes it more aligned with the Demand Creation Theory. The "Confusion Theory" is less convincing because the Design Law contains separate provisions for novelty and creative step requirements (which are hard to explain under a pure confusion rationale) and a distinct provision (Article 5, Item 2) that directly addresses unregistrable designs likely to cause confusion with another person's business. Modern Japanese court practice in design similarity cases often focuses on the commonality of aesthetic impression without dwelling on "confusion" of articles.

The "General Consumer" Standard:

The Supreme Court referred to the "general consumer" as the subject for judging aesthetic similarity under Article 3(1)(iii). This should not be taken as any layperson, but rather a consumer who is reasonably observant and somewhat experienced in the specific field of the article in question. The JPO's Design Examination Guidelines also refer to the judging subject as "consumers (including traders)" and state this should be an "appropriate person according to the actual conditions of trade and distribution of the article."

"Similarity" in Registration (Art. 3(1)(iii)) vs. Infringement (Art. 23)

The Design Law, in Article 23, states that the effect of a design right extends to designs "similar" to the registered design. The Supreme Court in the Flexible Hose case linked its interpretation of "similarity" under Article 3(1)(iii) (aesthetic impression for consumers) to this scope of right, implying that similarity for infringement purposes (Article 23) is also judged from the consumer's aesthetic viewpoint. This understanding was later codified in a 2006 amendment to the Design Law, which added Article 24, Paragraph 2, stating that the similarity of a registered design and another design "shall be judged based upon the aesthetic impression that the designs evoke through the eye of their consumers." While directly guiding Article 23, this also informs the interpretation of Article 3(1)(iii).

A nuanced difference:

- Article 3(1)(iii) (for registration/novelty): This provision assesses whether an applied-for design is new compared to prior art designs. The focus is on whether the applied-for design possesses its own distinct aesthetic impression from the consumer's viewpoint. Its creativity is a separate question under Article 3(2).

- Article 23 (for infringement scope): This provision presumes the registered design is already novel and creative. The inquiry is whether an accused design shares the creative aesthetic characteristics of the registered design, thereby evoking a similar overall aesthetic impression. This often involves identifying the creatively distinctive parts (the "essential features" or "要部" - yōbu) of the registered design by considering prior art. If the aesthetic commonality between the registered design and an accused design stems only from well-known or commonplace features, infringement should not be found, as the Design Law protects creative forms.

Conclusion

The Flexible Hose Supreme Court decision is a landmark in Japanese design law for its critical clarification of the distinct yet complementary roles of design similarity and ease of creation as grounds for unregistrability. It established that Article 3, Paragraph 1, Item 3 (similarity to prior designs) is judged based on the overall aesthetic impression from the perspective of a general consumer, while Article 3, Paragraph 2 (ease of creation) is judged based on the inventive step or originality of conception from the perspective of a person skilled in the art, using widely known motifs as a reference. The Court confirmed that these are separate inquiries and that both can be applied even when the designs pertain to identical or similar articles. This ruling corrected a narrower interpretation by the lower court and has since guided the JPO and courts in applying these fundamental standards for design protection, emphasizing that a registrable design must not only be aesthetically different from what came before but must also represent a non-obvious creative contribution.