Adoption for Tax Savings: Japanese Supreme Court Upholds Validity When "Intention to Adopt" Exists

Judgment Date: January 31, 2017

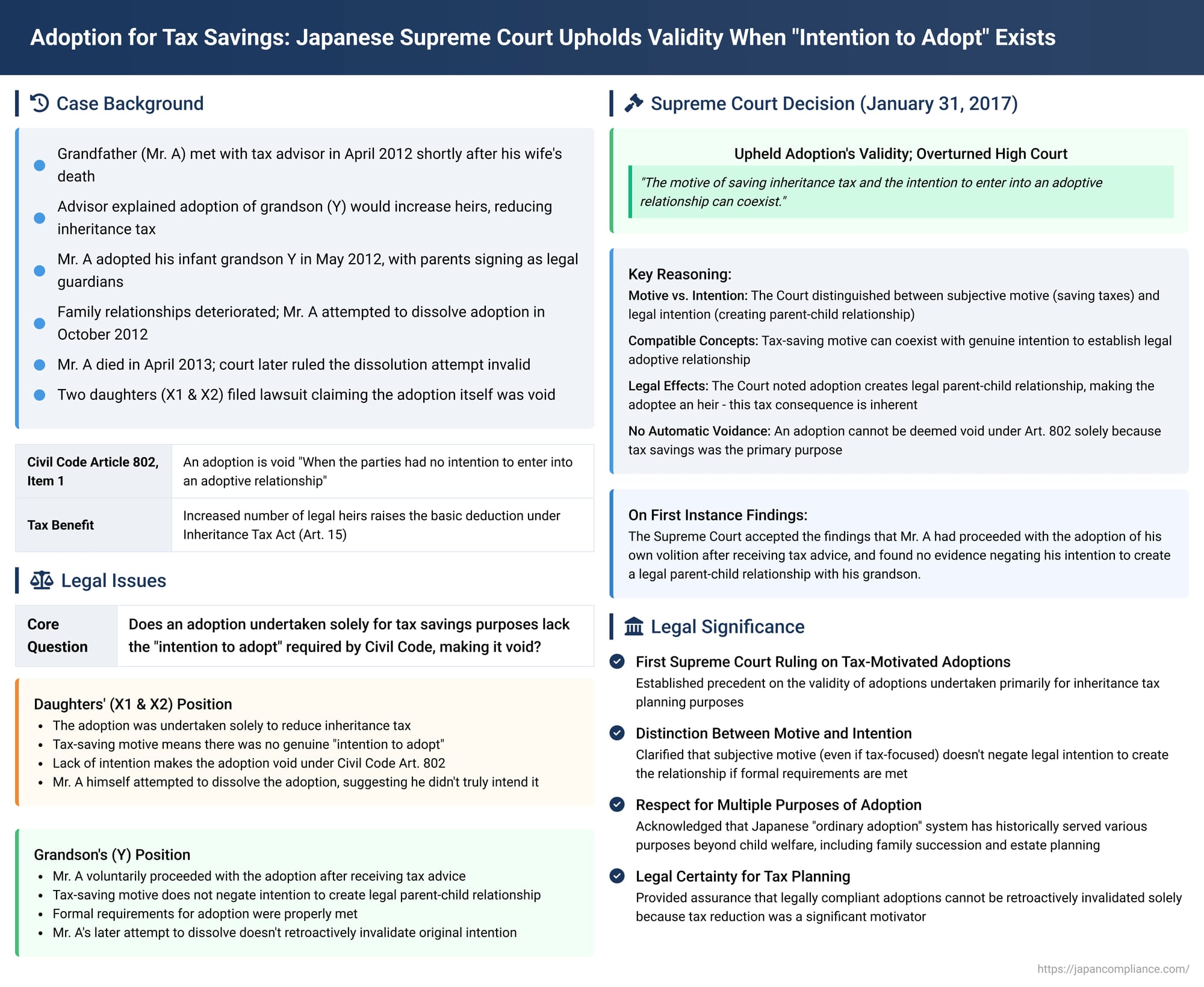

In a significant decision addressing the intersection of family law and tax planning, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan ruled on the validity of an adoption allegedly entered into solely for the purpose of reducing inheritance tax. The Court held that even if the primary motivation for an adoption is tax savings, the adoption is not automatically void for lack of "intention to adopt," provided the parties genuinely intend to establish a legal parent-child relationship. This ruling provides crucial clarity on the permissibility of what are commonly known as "tax-saving adoptions" in Japan.

Background: A Family Adoption and an Inheritance Tax Dispute

The case involved the estate of the deceased Mr. A, who passed away in 2013. Mr. A and his late wife (who predeceased him in March 2012) had three children: two daughters, X1 and X2 (the plaintiffs/respondents on appeal), and a son, B. The defendant/appellant, Y, was Mr. A's grandson, born to B and B's wife, C, in 2011.

The sequence of events leading to the dispute was as follows:

- Tax Advice and Adoption (April-May 2012): In April 2012, Mr. A, accompanied by his son B, daughter-in-law C, and infant grandson Y, met with a tax advisor at Mr. A's home. During this meeting, the advisor explained that if Mr. A adopted his grandson Y, it would increase the number of legal heirs. This, in turn, would raise the basic deduction applicable to Mr. A's estate under the Inheritance Tax Act (Article 15), thereby leading to a reduction in the overall inheritance tax liability.

Following this advice, an application for adoption was prepared. B and C, as Y's parents and legal guardians (holders of parental authority), signed the application on behalf of Y (the adoptee). Mr. A signed as the adopter. Mr. A's younger brother and his wife signed as witnesses. In May 2012, this adoption application was formally submitted to and accepted by the Setagaya Ward office in Tokyo, establishing a legal adoptive relationship between Mr. A and his grandson Y ("the subject adoption"). - Deteriorating Family Relations and Attempted Dissolution (June-October 2012): Around June 2012, the relationship between Mr. A and his son B soured, with B reportedly refusing contact from Mr. A. On October 7, 2012, Mr. A sent a written communication to B. In it, Mr. A claimed that the adoption of Y had been B's unilateral decision, that he (Mr. A) had not received a thorough explanation about it, and that he had no recollection of signing the adoption papers. Mr. A stated his intention to file for a dissolution of the adoptive relationship.

Subsequently, on October 12, 2012, Mr. A signed and submitted a notification of dissolution of the adoptive relationship with Y to the Setagaya Ward office, which was accepted. - Legal Challenges (2013-2014): In February 2013, Y (represented by his parents B and C) initiated a lawsuit against Mr. A, seeking a declaration that the dissolution of the adoption was invalid. Mr. A passed away in April 2013. Before his death, he had filed a counterclaim in Y's lawsuit, seeking a declaration that the original adoption itself was invalid.

Upon Mr. A's death, his counterclaim regarding the invalidity of the adoption automatically terminated. However, Y's lawsuit challenging the dissolution proceeded, with a public prosecutor stepping in as the defendant to represent the interests of Mr. A's estate. On March 10, 2014, a court ruled that the dissolution of the adoption was indeed invalid, primarily because it lacked the proper consent from Y's legal guardians (his parents, B and C). This judgment became final and binding on March 26, 2014. - Current Lawsuit by Daughters (X1 and X2): With the dissolution attempt having failed, Mr. A's daughters, X1 and X2, filed the present lawsuit. They sought a judicial declaration that the subject adoption of Y by Mr. A was void from the outset. Their central argument was that Mr. A lacked the genuine "intention to enter into an adoptive relationship" (縁組をする意思 - engumi o suru ishi), as required by Article 802, Item 1 of the Japanese Civil Code, because, they alleged, the adoption was motivated solely by the purpose of reducing inheritance tax.

The Legal Question: Intention to Adopt vs. Tax-Saving Motive

The core legal issue before the courts was the interpretation of Article 802, Item 1 of the Civil Code, which states that an adoption is void: "When the parties had no intention to enter into an adoptive relationship."

The question was whether an adoption undertaken "solely for the purpose of saving inheritance tax" automatically signifies a lack of this requisite intention, thereby rendering the adoption legally void.

Lower Court Rulings

- Tokyo Family Court (First Instance): This court dismissed the daughters' (X1 and X2) claim. It found that Mr. A had proceeded with the adoption after receiving advice from a tax advisor about the tax benefits. The court concluded that the adoption was based on Mr. A's will and found no sufficient evidence to suggest that Mr. A lacked either the intention to adopt Y or the intention to file the adoption notification at the time it was made.

- Tokyo High Court (Appellate Court): The High Court reversed the Family Court's decision. It found that the subject adoption had indeed been carried out solely for the purpose of reducing inheritance tax. Crucially, the High Court held that such a situation—an adoption motivated exclusively by tax savings—does fall within the scope of Civil Code Article 802, Item 1, meaning there was "no intention to enter into an adoptive relationship." Consequently, the High Court declared the adoption void, siding with X1 and X2. Y (the adopted grandson) then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Separating Motive from Intention

The Supreme Court disagreed with the Tokyo High Court's interpretation and reasoning. It reversed the High Court's judgment and reinstated the first instance decision of the Tokyo Family Court, which had upheld the validity of the adoption.

The Supreme Court's analysis focused on the distinction between the motive behind an adoption and the legal intention to create an adoptive relationship:

- Nature and Effects of Adoption: The Court began by stating the fundamental legal nature of adoption: it creates a legal parent-child relationship equivalent to that of a biological (legitimate) parent and child. A significant consequence of this is that an adopted child becomes a legal heir of the adopter.

- Source of Tax Benefits: The inheritance tax saving effect that arises from an adoption (such as an increased basic estate tax deduction due to a larger number of legal heirs) is a consequence of specific provisions within the Inheritance Tax Act itself.

- Defining "Adoption for Tax Saving": The Court characterized "adopting for the purpose of saving inheritance tax" as nothing more than entering into an adoption motivated by the desire to bring about such tax-saving effects.

- Coexistence of Motive and Legal Intention: This was the crux of the Supreme Court's reasoning. It stated: "The motive of saving inheritance tax and the intention to enter into an adoptive relationship can coexist." (相続税の節税の動機と縁組をする意思とは、併存し得るものである。)

- Conclusion on Validity: Based on this principle, the Court concluded: "Therefore, even in a case where an adoption is entered into solely for the purpose of saving inheritance tax, it cannot be immediately concluded that said adoption falls under 'when the parties had no intention to enter into an adoptive relationship' as stipulated in Article 802, Item 1 of the Civil Code."

Applying this to the facts of the case as established (presumably drawing from the first instance court's findings that Mr. A acted on his own will after receiving tax advice), the Supreme Court found no circumstances that would suggest a lack of intention on Mr. A's part to actually form an adoptive relationship with Y. The mere presence of a tax-saving motive, even if it was the predominant or sole motive, was not enough to invalidate the adoption as long as the intention to create the legal parent-child status was present.

Judgment and Reinstatement of First Instance Ruling

The Supreme Court found that the Tokyo High Court's judgment, which had equated a sole tax-saving motive with a lack of intention to adopt, contained a violation of law that clearly affected the outcome. The appeal by Y was therefore deemed to have merit. The Supreme Court reversed the High Court's decision and, in doing so, reinstated the original judgment of the Tokyo Family Court, which had dismissed the daughters' (X1 and X2) claim to invalidate the adoption. Thus, the adoption of Y by Mr. A was held to be legally valid.

Significance and Implications

This Supreme Court decision is of considerable importance in Japan for several reasons:

- First Supreme Court Ruling on "Tax-Saving Adoptions": It was the first time the nation's highest court directly addressed the validity of adoptions primarily motivated by inheritance tax reduction.

- Distinction Between Motive and Intention: The ruling clearly distinguishes between the subjective motive for an action (e.g., saving taxes) and the legal intention required to perform that action (e.g., the intent to create a legal parent-child relationship through adoption). It establishes that a strong, or even sole, tax-saving motive does not, by itself, negate the legal intention to adopt.

- Upholding a Traditional View of Ordinary Adoption: The decision aligns with the broad understanding of "ordinary adoption" (普通養子縁組 - futsū yōshi engumi) in Japanese civil law. Unlike "special adoptions" (特別養子縁組 - tokubetsu yōshi engumi), which are primarily focused on child welfare and aim to create a relationship virtually identical to a biological one (often severing ties with biological parents), ordinary adoptions have historically served a variety of purposes in Japan. These have included ensuring family succession (especially in the absence of a male heir), providing for old age, and, as seen in this case, estate planning. The Court's decision implicitly acknowledges this flexibility.

- Implications for Tax Planning: The ruling provides a degree of legal certainty for individuals considering adoption as part of their estate planning strategy. As long as the formal requirements for adoption are met and there is a genuine intent to establish the legal relationship of parent and child, the fact that tax reduction is a significant motivator will not, on its own, invalidate the adoption.

- "Intention to Adopt" Remains Key: It is important to note that the Court did not say that all tax-motivated adoptions are valid. The core requirement of Article 802, Item 1 of the Civil Code—the "intention to enter into an adoptive relationship"—must still be present. If it could be proven that the parties were merely feigning an adoption with no true intent to create a parent-child bond (e.g., a "sham" adoption solely on paper for an ulterior purpose unrelated to family ties), such an adoption could still be challenged as void. However, the desire to achieve a legal consequence of adoption (like becoming an heir and thus affecting tax calculations) is not inherently contradictory to intending the adoption itself.

This judgment navigates the delicate balance between respecting individuals' autonomy in family matters and addressing concerns about tax planning. While the Court focused narrowly on the civil law requirements for a valid adoption, the case inevitably touches upon broader discussions about the distinction between legitimate tax saving (節税 - setsuzei) and potentially abusive tax avoidance (租税回避 - sozei kaihi) – a complex area where legal lines can often be debated. The Supreme Court, in this instance, affirmed that as long as the legal form and intention for an adoption are met, the tax consequences that flow from that valid legal act are a matter for the tax laws themselves.