Adoption for Tax Breaks: A Valid Family Strategy in Japan? The Supreme Court Weighs In

Judgment Date: January 31, 2017 (Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench)

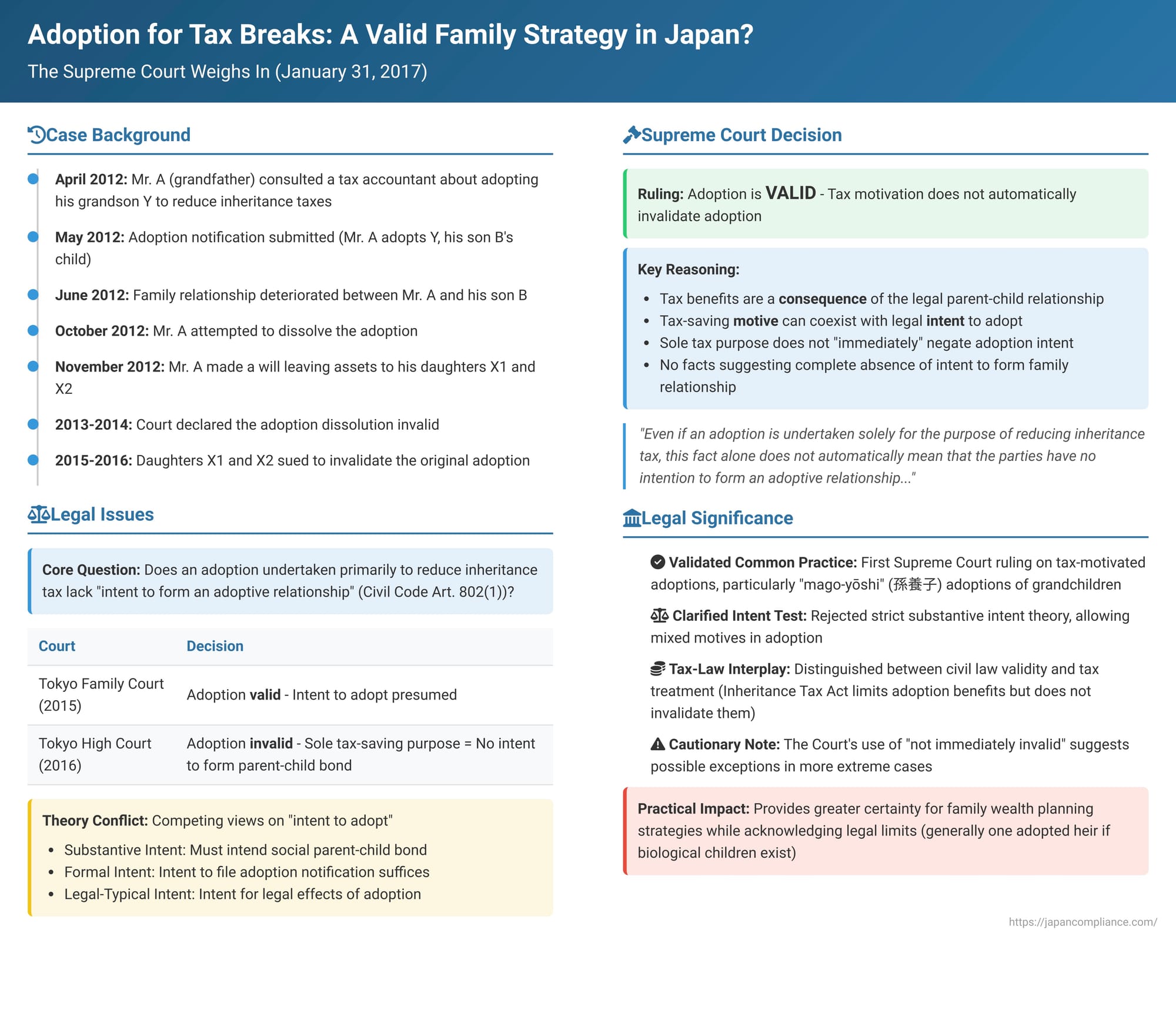

In a closely watched case with significant implications for estate planning and family law in Japan, the Supreme Court ruled in 2017 that adopting a grandchild primarily for the purpose of reducing inheritance tax does not automatically invalidate the adoption. This decision clarified that the motivation to achieve tax benefits can legally coexist with the fundamental intent required to form an adoptive parent-child relationship, offering a degree of reassurance to families employing such strategies, while also underscoring the nuanced interpretation of "intent" in Japanese adoption law.

A Family Affair: An Adoption and Its Aftermath

The case involved a family patriarch, Mr. A. He had two daughters, Ms. X1 and Ms. X2 (the plaintiffs who would later challenge the adoption), and an eldest son, Mr. B. The defendant, Y, was Mr. B's son, born in 2011, making him Mr. A's grandson.

Mr. A's wife passed away in March 2012. Just a month later, in April 2012, Mr. A, accompanied by his son Mr. B, B's wife, and his young grandson Y, met with a tax accountant. During this meeting, Mr. A received an explanation regarding the potential inheritance tax savings if he were to adopt Y. The primary benefit discussed was the increase in the basic estate deduction, which is calculated based on the number of statutory heirs.

Following this consultation, an official adoption notification form was prepared. Mr. B and his wife signed as the legal representatives of Y (who was a minor). Mr. A signed as the adopting parent. Mr. A's younger brother and his wife acted as witnesses to the adoption. The completed form was submitted to the ward office in May 2012, formalizing the adoption of Y by his grandfather, Mr. A.

However, the family dynamics soon soured. Around June 2012, Mr. A's relationship with his son, Mr. B, deteriorated, reportedly due to Mr. B's probing into alleged romantic affairs of Mr. A. By October 2012, Mr. A expressed a change of heart regarding the adoption. In a written statement to Mr. B, he claimed the adoption was Mr. B's unilateral decision, that he (Mr. A) had not been properly informed, had not actually signed the adoption form, and, given his age, would not be able to raise Y. On October 12, 2012, Mr. A submitted a notification to dissolve the adoption with Y. (Mr. B and his wife were not involved in preparing this dissolution document.)

The following month, November 2012, Mr. A executed a notarized will, stipulating that all his assets should be inherited by his daughters, Ms. X1 and Ms. X2.

The legal battles began shortly thereafter. Around February 2013, Y (represented by his parents, Mr. B and his wife) initiated a lawsuit against Mr. A to confirm the invalidity of the adoption dissolution, arguing it was improperly filed. Mr. A, in turn, filed a counterclaim in April 2013 seeking to confirm the invalidity of the adoption itself. However, Mr. A passed away before this counterclaim could be resolved, leading to its termination. The lawsuit concerning the dissolution's validity continued, with the public prosecutor eventually stepping in as the defendant after Mr. A's death. In March 2014, a court ruled that the adoption dissolution was indeed invalid because it lacked the consent of Y's legal representatives (his parents, Mr. B and his wife). This judgment became final.

With the adoption dissolution invalidated (meaning the adoption was, for the time being, legally intact), Mr. A's daughters, Ms. X1 and Ms. X2, launched the present lawsuit. They sought a court declaration that the original adoption of Y by Mr. A was invalid from the outset, primarily arguing that Mr. A lacked the genuine intent to form an adoptive relationship and the intent to file the adoption notification.

The Legal Challenge: Lower Courts Clash on "Intent to Adopt"

The validity of the adoption was fiercely contested in the lower courts, leading to conflicting outcomes:

- Tokyo Family Court (September 16, 2015): Dismissed the daughters' claim. The court presumed that Mr. A did possess the intent to adopt Y and that the adoption notification was based on his genuine will. Thus, the adoption was considered valid.

- Tokyo High Court (February 3, 2016): Reversed the Family Court's decision. The High Court found that the adoption was undertaken solely for the purpose of reducing inheritance tax, primarily for the benefit of Mr. A's heirs (and particularly his son, Mr. B). It concluded that neither Mr. A nor Y's parents (Mr. B and his wife) possessed the true intent to create a genuine parent-child relationship between Mr. A and Y. On this basis, the High Court declared the adoption invalid.

Y (the adopted grandson, through his representatives) then appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Verdict: Tax-Saving Motive Does Not Automatically Invalidate Adoption

In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court overturned the Tokyo High Court's ruling and reinstated the Tokyo Family Court's initial judgment. This meant the adoption of Y by his grandfather, Mr. A, was deemed valid.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was clear and direct:

- Nature of Adoption and Tax Effects: An adoption legally creates a legitimate parent-child relationship, and as a consequence, the adopted child becomes a legal heir of the adopter. The inheritance tax-saving effects associated with adoption (such as an increased basic deduction due to a larger number of heirs) are a result of specific provisions within the Inheritance Tax Act.

- Motive vs. Intent: Engaging in an adoption for the purpose of saving inheritance tax is simply a scenario where the adoption is motivated by the desire to achieve these tax benefits. The Supreme Court explicitly stated that a motive to save on inheritance tax and the legal intent to form an adoptive relationship can coexist.

- Sole Tax-Saving Purpose Not Conclusive: Therefore, even if an adoption is undertaken solely for the purpose of reducing inheritance tax, this fact alone does not automatically mean that the parties "have no intention to form an adoptive relationship" as stipulated in Article 802, Item 1 of the Civil Code (which is a ground for declaring an adoption invalid).

- Application to the Case: Based on the established facts, the Court found no circumstances that would suggest a lack of intent on Mr. A's part to form an adoptive relationship with Y. Thus, the condition for invalidity under Article 802, Item 1 was not met.

The "Intent to Adopt": A Complex Legal Concept

The core of this case revolved around the meaning of "intent to form an adoptive relationship" (縁組をする意思, engumi o suru ishi). Japanese law (Civil Code Article 802(1)) states an adoption is invalid if such intent is lacking. However, the precise nature of this requisite intent has been a subject of ongoing academic debate:

- Substantive Intent Theory (実質的意思説, jisshitsu-teki ishi-setsu): The traditional majority view, this theory posits that the parties must intend to create a relationship that is recognized as a parent-child bond according to societal customs and norms (e.g., involving care, upbringing, emotional connection).

- Formal Intent Theory (形式的意思説, keishiki-teki ishi-setsu): This view argues that an intent directed merely at the act of filing the official adoption notification is sufficient. Reasons include the formal nature of the registration, the difficulty of objectively determining "true" underlying intentions, and the principle that parties should be bound by their formal declarations.

- Legal-Typical Intent Theory (法律的定型説, hōritsu-teki teikei-setsu): An influential theory holding that the parties must intend the creation of the typical legal effects that the Civil Code associates with adoption (such as rights and duties concerning parental authority, support, and inheritance). If this intent, while present, is aimed at a purpose that lacks social appropriateness, the adoption might still be voided under Article 90 of the Civil Code (acts contrary to public order and morality).

Previous Supreme Court decisions had invalidated adoptions clearly undertaken for improper ulterior motives (e.g., draft evasion, disguising human trafficking). However, the Court had also upheld adoptions where inheritance was a significant motive, provided there was also an intention to create some form of familial or supportive bond. These varied precedents left the precise judicial stance on "intent" somewhat ambiguous, though often leaning away from a strict application of the substantive intent theory if it meant ignoring other valid personal or financial objectives.

Tax-Saving Adoptions in Japanese Law and Practice

This 2017 ruling was the Supreme Court's first direct judgment on the validity of an adoption motivated primarily by inheritance tax reduction. The practice of adopting, for example, a son's wife or grandchildren to increase the number of heirs and thereby reduce the taxable estate had become relatively common in Japan since the mid-1980s.

The Inheritance Tax Act itself acknowledges and, to some extent, regulates this practice:

- A 1988 amendment placed limits on the number of adopted children that can be counted for calculating the total inheritance tax liability (generally, one adopted child if the deceased has biological children, and two if not).

- The Act also contains a provision (Article 63) allowing tax authorities to disregard an adoption if it is deemed to result in an unfair reduction of the tax burden. However, this provision is reportedly difficult for tax authorities to apply in individual cases and, crucially, such a tax re-assessment does not invalidate the adoption itself under private (Civil Code) law.

The Supreme Court's 2017 decision aligns with this understanding that tax law may regulate the fiscal consequences of adoption, but the validity of the adoption as a family law act is a separate matter determined by the Civil Code.

The "Not Immediately Invalid" Caveat

It is noteworthy that the Supreme Court stated that a sole tax-saving motive does not "直ちに (tadachi ni - at once, immediately, directly)" render the adoption invalid. This phrasing suggests that while a tax-saving purpose alone is not a fatal flaw, there might be other accompanying circumstances in a different case that could negate the fundamental intent to form an adoptive relationship. However, in the present case, the Court found no such overriding circumstances.

Adopting Minors, Especially Grandchildren (孫養子, Mago-Yōshi)

The Supreme Court's decision affirmed the validity of this specific tax-motivated adoption of a minor grandchild. This has broader implications:

- Adult Adoptions: In adult adoptions, the relationship often centers on providing for mutual support or facilitating inheritance, making the adoption a "legal technique for financial provision."

- Minor Adoptions: The adoption of minors, particularly by grandparents, for such purposes raises distinct considerations because minors do not make the decision themselves. Some legal scholars argue for caution in applying purely contractual or financial reasoning to minor adoptions. They contend that the "intent to adopt" a minor should primarily encompass the intention to provide care and education, aligning with the modern understanding of adoption involving the assumption of full parental responsibilities. The Family Court usually has a role in approving adoptions of minors (Civil Code Art. 798), though adoptions by lineal ascendants like grandparents are an exception to this prior court approval requirement.

There are differing perspectives on whether primarily financial benefits, if no substantial harm occurs, are sufficient to deem a grandchild adoption as being in the child's interest, versus a view that emphasizes the adopter's commitment to the duties of parental authority and upbringing.

The Broader Context of Adoption in Japan

Japan's adoption system has historically been quite flexible, accommodating a wide range of motivations, some of which may not fit a "standard" image of a parent-child relationship. This flexibility arises from relatively lenient rules on who can adopt and be adopted, a simple notification-based procedure, and the broad legal effects that adoption entails. Consequently, judging the "intent to adopt" solely against a narrow, traditional concept of parent-child relations has proven difficult (e.g., adoptions between same-sex prison inmates for mutual support have been upheld).

Conclusion: Pragmatism in the Face of Financial Planning

The Supreme Court's 2017 decision brings a significant measure of clarity to the practice of "tax-saving adoptions" in Japan. It establishes that the motivation to reduce inheritance tax, even if it is the primary driver for the adoption, does not, by itself, nullify the essential legal intent to form an adoptive parent-child relationship. This ruling acknowledges the practical reality that financial planning and family formation can be intertwined.

While the decision provides a green light for such adoptions within the bounds of tax law limitations, it also implicitly leaves room for judicial scrutiny if other factors suggest a complete absence of any genuine intent to create a familial bond or if the adoption is a mere sham for entirely illicit purposes. The ongoing debate, especially concerning the adoption of minors for predominantly financial reasons, indicates that the societal and legal understanding of adoption's multifaceted purposes continues to evolve.