Administrator's Powers and Tenant's Set-Off Rights in Secured Real Property Revenue Execution: A 2009 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

Case Name: Claim for Rent, etc.

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Case Number: Heisei 19 (Ju) No. 1538

Date of Judgment: July 3, 2009

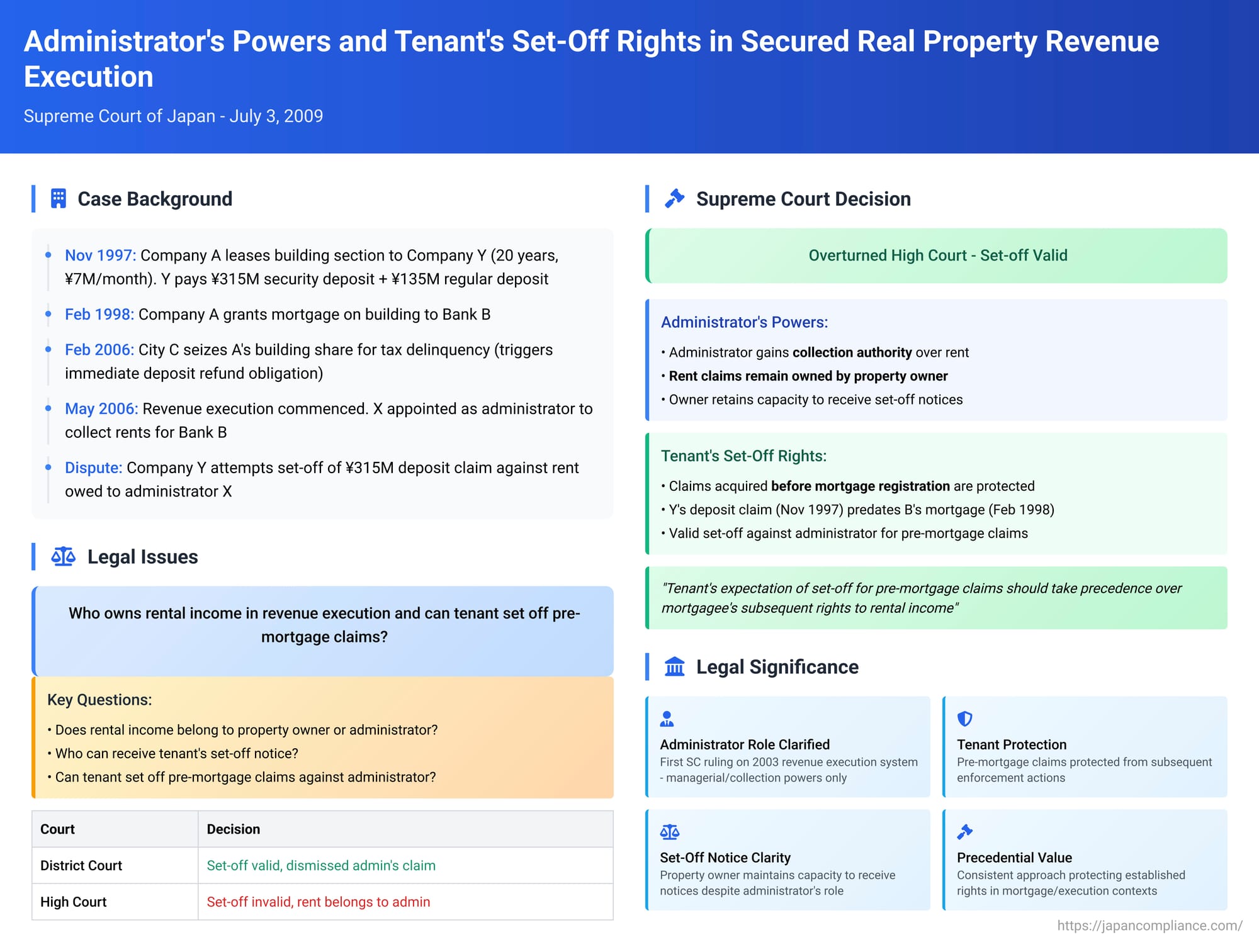

This article analyzes a landmark Japanese Supreme Court judgment dated July 3, 2009. The decision provides crucial clarifications on the scope of an administrator's powers in a "secured real property revenue execution" (tanpo fudōsan shūeki shikkō)—a mechanism allowing mortgagees to collect revenue from mortgaged property—and a tenant's right to set off pre-existing claims against rent payments due to the administrator. This was one of the first Supreme Court rulings to interpret the then relatively new revenue execution system introduced by the 2003 amendments to Japan's security and execution laws.

Factual Matrix: Lease, Deposits, Mortgage, and Set-Off

The case involved a complex interplay of agreements and enforcement actions:

- The Lease and Deposits:

- On November 20, 1997, Company A, a co-owner of a building, leased a section of it to Company Y (the tenant, appellant in the Supreme Court) for a 20-year term. The monthly rent was JPY 7 million.

- Upon concluding the lease, Company A received from Company Y a substantial "security deposit" (hoshōkin) of JPY 315 million (with a specific repayment schedule in installments from the 11th to the 20th year of the lease) and a regular deposit (shikikin) of JPY 135 million.

- Mortgage and Subsequent Agreements:

- On February 27, 1998, Company A granted a mortgage on the building to Bank B.

- Later, Company A and Company Y agreed that if Company A faced attachment or other enforcement actions from its other creditors, Company A would lose the "benefit of time" for the repayment of the security deposit, meaning the refund would become immediately due and payable.

- Triggering Events and Revenue Execution:

- On February 14, 2006, City C, a tax authority, placed a seizure on Company A's share in the building due to tax delinquency. This event triggered the clause making Company A's security deposit refund obligation to Company Y immediately due.

- On May 19, 2006, secured real property revenue execution proceedings were commenced against the building based on Bank B's mortgage. Mr. X (the appellee in the Supreme Court) was appointed as the administrator (kanrinin) to manage the property and collect its revenue.

- Attempted Set-Off:

- Company Y made some partial rent payments to Mr. X, the administrator.

- Subsequently, Company Y notified Company A (the lessor) of its intention to set off (sōsai) its outstanding security deposit refund claim (the active claim or jidō saiken) against the remaining rent owed (the passive claim or judō saiken). This attempted set-off became the focal point of the dispute.

- Mr. X then sued Company Y for the unpaid portion of the rent and associated late payment charges.

The Legal Battleground: Key Issues at Stake

The case raised several critical legal questions regarding the revenue execution process:

- Does the rental income generated after the commencement of a revenue execution accrue to the property owner or to the court-appointed administrator?

- Who is the proper party to receive a tenant's notice of set-off concerning rent claims subject to revenue execution—the owner or the administrator?

- Can a tenant validly set off a claim they hold against the property owner (such as a security deposit refund that became due before the mortgage was registered) against rent payments that are being collected by the administrator under a revenue execution?

Lower Courts' Divergent Paths

- Kofu District Court (First Instance): The District Court found the set-off by Company Y to be valid and dismissed Mr. X's (the administrator's) claim for unpaid rent.

- Tokyo High Court (Appellate Court): The High Court reversed this decision in part. It reasoned that rental income arising after the revenue execution commenced belonged to the administrator, Mr. X, not Company A. Therefore, there was no mutuality of debts between Company Y's claim against Company A and the rent owed to Mr. X, rendering the set-off ineffective. Alternatively, the High Court suggested that Mr. X was the only proper recipient of the set-off notice. It thus partially upheld Mr. X's claim.

Company Y appealed the High Court's unfavorable ruling to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Clarifications

The Supreme Court, in its judgment on July 3, 2009, overturned the High Court's decision concerning the disallowed set-off and ultimately upheld the first instance court's dismissal of the administrator's claim. The Supreme Court's reasoning was delivered in two main parts:

I. On the Administrator's Powers and Ownership of Rental Income:

- Nature of Revenue Execution: Secured real property revenue execution is an enforcement method where the execution court seizes the mortgaged property, thereby divesting the owner of their rights to manage it and collect its revenue. These rights are then entrusted to a court-appointed administrator.

- Administrator's Collection Authority: As the administrator acquires the right to manage and collect revenue, tenants become obligated to pay rent to the administrator, not the property owner. This mechanism is designed to ensure that the property's income is reliably applied towards satisfying the secured creditor's claim. However, the administrator is not granted the power to dispose of the property itself.

- Ownership of Rent Claims: Crucially, the Supreme Court held that the administrator acquires the authority to exercise the rights to collect revenue (such as rent claims), but the rent claims themselves remain vested in the property owner even after the revenue execution has commenced. This principle applies equally to rent installments that fall due after the commencement of the execution.

- Recipient of Set-Off Notice: Consequently, the property owner does not lose the capacity to receive a tenant's notice of set-off where the rent owed by the tenant is the passive claim in the set-off. In this case, Company A, as the lessor and co-owner, remained competent to receive Company Y's notice of set-off.

II. On the Tenant's Right to Set Off Pre-Mortgage Claims Against the Administrator:

- Protection of Tenant's Expectation of Set-Off: The Supreme Court reasoned that when a tenant acquires a claim against their lessor (the property owner) before a mortgage is registered on the leased property, the tenant's expectation of being able to set off this claim against future rent payments should be protected and should take precedence over the mortgagee's subsequent rights to the rental income. This drew an analogy from a prior Supreme Court ruling concerning a tenant's right to set off against a mortgagee exercising direct subrogation rights over rental income (Sup. Ct., March 13, 2001, Minshū Vol. 55, No. 2, p. 363).

- Assertion of Set-Off Against Administrator: Therefore, even after revenue execution commences, a tenant can validly assert a set-off against the administrator if the active claim (the tenant's claim against the owner) was acquired before the mortgage registration and is being set off against rent claims (the passive claim).

- Application to the Case: In this instance, Company Y acquired its security deposit refund claim against Company A when the lease was signed in November 1997, which was before Bank B's mortgage was registered in February 1998. The conditions for set-off (mutuality of matured debts) were met when Company Y declared its intention to set off. Thus, Company Y could validly assert this set-off against Mr. X, the administrator.

The Supreme Court concluded that the rent claimed by Mr. X had been extinguished by Company Y's partial payments and the valid set-off.

Analysis and Significance

This 2009 Supreme Court judgment carries significant weight for several reasons:

- Administrator's Role Defined: It was a pioneering Supreme Court decision clarifying the administrator's role in the relatively new secured real property revenue execution system. The ruling establishes that while the administrator has the power to collect and manage rents, the underlying rental claims still belong to the property owner. This distinction is vital for issues like set-off and determining the proper parties for legal notices.

- Tenant Protection for Pre-Mortgage Claims: The decision strongly protects tenants who have claims against their lessor (e.g., for security deposit refunds) that arose before the lessor mortgaged the property. Their ability to set off these claims against rent is preserved even when a revenue execution administrator steps in to collect rent for a mortgagee. This upholds the general principle that a mortgage should not retroactively impair superior pre-existing rights.

- Guidance on Set-Off Notices: By confirming the owner's capacity to receive a set-off notice, the judgment provides clarity. Legal commentary suggests that the administrator might also be considered a proper recipient of such a notice, given their authority to manage and collect the rent.

- Analogical Reasoning: The Court's reliance on precedents from mortgage subrogation cases to determine set-off rights in revenue execution proceedings shows a consistent approach to protecting tenant expectations. However, some commentators have questioned the direct applicability of these precedents due to differences in the statutory foundations of subrogation versus revenue execution.

- Distinction from Regular Deposits (Shikikin): The case specifically involved a large, long-term "security deposit" (hoshōkin) with a defined repayment schedule. The commentary suggests that the principles might apply differently to regular deposits (shikikin), which are typically held to cover damages or unpaid rent and are automatically set off upon termination of the lease and vacation of the premises.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's July 3, 2009, decision provided essential clarifications on the then-novel secured real property revenue execution system in Japan. It delineated the administrator's powers as primarily managerial and collection-oriented, with the underlying rental income claims remaining with the property owner. Most importantly, it robustly defended a tenant's right to set off claims against the lessor that predate a mortgage registration, even when rent is being collected by an administrator for the benefit of the mortgagee. This ruling offers critical guidance for tenants, landlords, mortgagees, and administrators involved in such execution proceedings, emphasizing the enduring strength of prior-established rights.