Administrative Delay vs. Public Order: A Japanese Supreme Court Case on 'Timing Discretion' in Permitting

Date of Judgment: April 23, 1982

Case: Damages Claim

Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, 1980 (O) No. 255

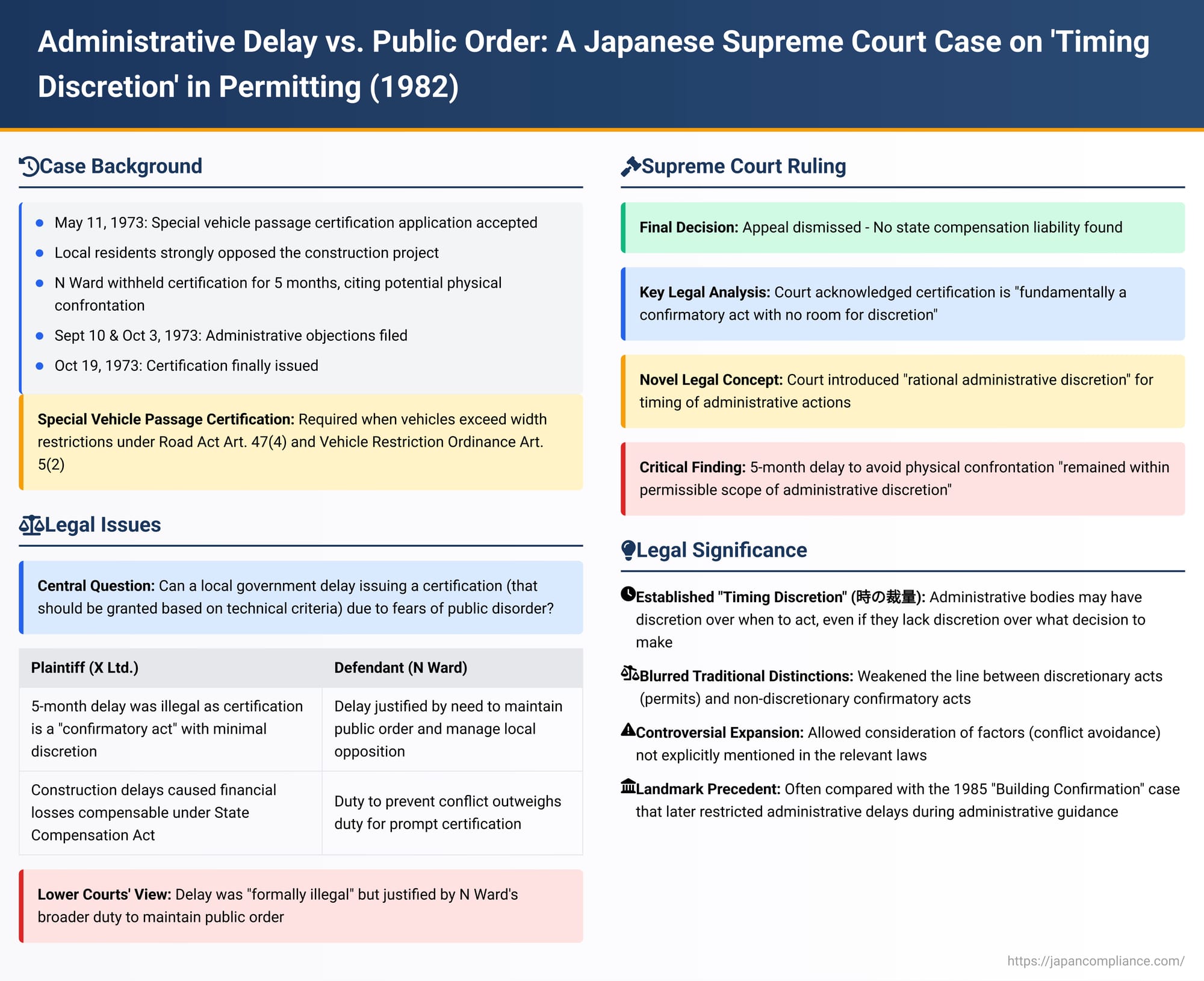

When businesses apply for necessary administrative approvals, there's a general expectation that such applications will be processed based on their legal merits and in a timely manner. But what happens when an administrative body delays a seemingly straightforward certification due to external pressures, such as intense local opposition to a project? A 1982 decision by the Supreme Court of Japan involving a "special vehicle passage certification" grappled with this issue, offering a nuanced perspective on administrative discretion, particularly concerning the timing of an agency's response, and its implications under the State Compensation Act.

The Factual Scenario: Construction, Opposition, and a Delayed Certification

The plaintiff, X Ltd., a real estate company, was embarking on the construction of a six-story apartment building. It had contracted with A Construction for the building work. A Construction, in turn, engaged B Reinforcement and C Transport to deliver essential construction materials to the site.

A problem arose: the vehicles designated for material transport exceeded the vehicle width restrictions stipulated by the Road Act (Article 47, Paragraph 4) and the Vehicle Restriction Ordinance (Article 5, Paragraph 2) for a local ward-managed road that was part of the access route to the construction site. Consequently, B Reinforcement and C Transport applied to Y, the N Ward of T City (the designated road administrator), for a "special vehicle passage certification" under Article 12 of the Vehicle Restriction Ordinance. This certification essentially acknowledges that a vehicle's non-compliance with standard restrictions is unavoidable due to its special structure or cargo. The application was formally accepted on May 11, 1973.

However, the certification was not forthcoming. The construction project faced significant opposition from local residents. Faced with this delay, on September 10, 1973, an administrative objection was filed under the (now old) Administrative Complaint Review Act, urging Y to take some action on the pending application. In response, Y informed the applicants that the certification would be "withheld" (or its processing "reserved") until amicable discussions between X Ltd. and the opposing residents led to a resolution, ensuring that the construction could proceed smoothly. Another similar objection was lodged on October 3, 1973.

Ultimately, Y issued the special vehicle passage certification on October 19, 1973. The entire process had taken approximately five months from the date the application was accepted.

X Ltd. subsequently sued Y (N Ward) under Article 1, Paragraph 1 of the State Compensation Act. X Ltd. argued that withholding the certification for over five months without any legally justifiable reason directly related to the certification criteria was illegal. This delay, X Ltd. claimed, led to significant construction delays and resultant financial losses.

The Legal Challenge and Lower Court Findings

The Tokyo District Court, as the court of first instance, acknowledged that the special vehicle passage certification under Vehicle Restriction Ordinance Article 12 is, by its nature, an act that typically leaves little room for administrative discretion. The road administrator is expected to objectively assess the facts against the criteria and either grant or deny the certification promptly. Therefore, the court found that withholding the certification for over five months was, "formally speaking, illegal".

However, the District Court then introduced a counter-argument. It reasoned that Y, as a local public entity, bears a responsibility for maintaining public order and ensuring the peace and tranquility of its residents (citing provisions of the Local Autonomy Act). The court concluded that prioritizing this broader duty to maintain local public order over the duty to promptly process the certification was, under the circumstances, an "unavoidable" course of action. The delay, in this view, was a necessary measure to fulfill this overarching responsibility, and this necessity "negated" the initial formal illegality. Consequently, X Ltd.'s claim for damages was dismissed.

The Tokyo High Court, on appeal, essentially agreed with the District Court's reasoning and upheld the dismissal. X Ltd. then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: A Nuance on Discretion

The Supreme Court, in its judgment on April 23, 1982, also dismissed X Ltd.'s appeal, thereby finding no grounds for state compensation. However, its reasoning diverged subtly but significantly from that of the lower courts.

Nature of the Special Vehicle Passage Certification:

The Court first analyzed the legal nature of the certification in question. It clarified that this certification, based on Road Act Article 47, Paragraph 4 and Vehicle Restriction Ordinance Article 12, is a determination of whether a vehicle's failure to meet specific dimensional standards (laid out in Articles 5 to 7 of the Ordinance) is "unavoidable due to the special structure of the vehicle or the special nature of the cargo it carries".

The Supreme Court emphasized that this "certification" (認定 - nintei) differs legally from a "permit" (許可 - kyoka), such as those under Road Act Article 47, Paragraphs 1 to 3, or Article 47-2, Paragraph 1, which lift a general prohibition on road use. The certification at issue, the Court stated, is "fundamentally of the nature of a confirmatory act (確認的行為 - kakuninteki kōi) with no room for discretion". This interpretation was based on the legislative history, the structure of the legal provisions, and the presence or absence of associated penalties.

Introduction of "Rational Administrative Discretion":

This is where the Supreme Court's reasoning took a pivotal turn. Despite characterizing the certification as fundamentally non-discretionary, the Court found that it would be inappropriate to conclude that all exercise of rational administrative discretion is entirely impermissible in this context. It pointed to two factors:

- The Vehicle Restriction Ordinance (Article 12, proviso) allows the road administrator to attach conditions to such certifications.

- The practical effect and utility of this certification system are almost indistinguishable from those of a permit system, where discretion is more commonly accepted.

Based on these considerations, the Court opined that when issuing such certifications, the exercise of "rational administrative discretion, including comparative balancing from a road administration perspective based on the specific circumstances of the case," could be permissible to some extent.

Application to the Delay in X Ltd.'s Case:

The Supreme Court then applied this framework to the facts. It noted that the N Ward's reason for withholding the certification for approximately five months was its assessment that granting it immediately would risk provoking a "physical confrontation" between X Ltd.'s representatives and the local residents opposing the construction project. The delay was a measure intended to "avoid this danger".

The Court acknowledged the five-month duration of the withholding but also observed that the Ward eventually did grant the certification once it determined that the initially anticipated risk of physical conflict had been averted.

Considering these specific circumstances—the reason for the delay (avoiding imminent conflict) and the eventual granting of the certification within a five-month period—the Supreme Court concluded that the N Ward's action of withholding the certification "remained within the permissible scope of the aforementioned administrative discretion". Therefore, the Court found no illegality as defined by Article 1, Paragraph 1 of the State Compensation Act, which requires an illegal act by a public official in the exercise of public power.

Dissecting the Decision: Key Principles and Implications

This Supreme Court decision is significant for its nuanced approach to administrative discretion and its potential ramifications for how administrative bodies handle applications in contentious situations.

- Flexibility in "Confirmatory Acts": Traditionally, Japanese administrative law, much like other legal systems, distinguishes between discretionary acts (like granting a permit based on broad criteria) and non-discretionary or "confirmatory" acts (where the agency merely verifies if specific, objective conditions are met). This ruling blurred that line by suggesting that even fundamentally confirmatory acts might allow for a degree of administrative discretion, particularly regarding their processing and timing when unique circumstances arise.

- The Concept of "Timing Discretion" (時の裁量 - toki no sairyō): Legal commentators have identified this case as prominently raising the issue of "timing discretion". This refers to an agency's discretion concerning when it performs an administrative act, such as issuing a certification. The Supreme Court, by upholding the delay, effectively permitted the N Ward to exercise discretion over the timing of the certification, influenced by factors (avoidance of local conflict) not explicitly mentioned as criteria in the Road Act or Vehicle Restriction Ordinance for the certification itself.

- Consideration of Extraneous Factors (Dispute Avoidance): The ruling is notable for allowing an administrative body to delay a technically due certification based on the risk of local conflict between a private applicant and opposing residents. While seemingly pragmatic, the PDF commentary accompanying this case raises questions about the general extent of an "authority to consider dispute avoidance" when administrative agencies make decisions. The primary purpose of the Road Act is road safety and maintenance, and incorporating "avoidance of physical confrontation" related to a construction project as a direct consideration under that Act could be seen as a significant expansion of its scope.

- Withholding Application Responses and "Administrative Guidance": Although the Supreme Court's judgment does not use the term "administrative guidance" (行政指導 - gyōsei shidō), the first-instance court's findings mentioned that the N Ward had attempted to mediate the dispute between X Ltd. and the opposing residents. This case is therefore often analyzed in the context of an agency withholding a formal response to an application while simultaneously engaging in informal administrative guidance aimed at resolving an underlying conflict related to the application's subject matter.

- Relation to the 1985 "Building Confirmation" Precedent: This 1982 decision is often compared with a leading Supreme Court judgment from 1985 (Showa 60.7.16, Minshu 39-5-989). The 1985 case concerned the withholding of a building confirmation (another type of largely confirmatory act) while administrative guidance was being provided to the applicant. In that later case, the Supreme Court held that withholding a building confirmation merely because administrative guidance is ongoing is illegal, unless there are "special circumstances where the applicant's non-cooperation with the administrative guidance can be said to be contrary to common sense notions of justice". Some scholars suggest that the 1982 ruling in X Ltd.'s case might be viewed as an instance where such "special circumstances"—specifically, the tangible risk of physical conflict—were implicitly found to exist, justifying the delay.

Impact on Administrative Practice

The 1982 Supreme Court decision has had a notable impact, particularly for local government administrations that frequently deal with development projects and associated local disputes.

- Legitimizing Delays for Dispute Management?: The ruling could be interpreted by some administrative bodies as providing a degree of legal cover for delaying even technically non-discretionary applications if such delays are aimed at mediating or preventing local conflicts. This is significant because the N Ward's standard processing time for such certifications is currently stated as about "one week," making the five-month delay in this case substantial.

- Concerns about Overreach: However, legal commentators express caution. The primary objectives of the Road Act and Vehicle Restriction Ordinance relate to road structure integrity and traffic safety. To broadly include "avoidance of physical confrontation between nearby residents and the applicant's side" as a primary consideration under these laws is arguably a considerable interpretive stretch. The extent to which this ruling can be applied to other types of administrative acts and different factual scenarios remains a complex question.

- Context of the Administrative Procedure Act (APA): After this ruling, Japan enacted its comprehensive Administrative Procedure Act in 1993, which includes general rules concerning the handling of applications and administrative guidance. Article 33 of the APA, which addresses the impropriety of disadvantaging an applicant for not complying with administrative guidance, is said to be influenced by the principles of the 1985 Supreme Court case on building confirmations. The 1982 decision provides an important case study when considering the application of these APA provisions and similar rules in local government administrative procedure ordinances.

- A Special Case?: It's also noted that this case had a peculiar institutional context. The N Ward, which delayed the special vehicle certification, did not actually have the authority to issue or deny the building confirmation for X Ltd.'s apartment project; that power rested with the T Metropolitan Government's architectural officials. The N Ward was, in effect, using its leverage over road access certifications to influence a broader construction-related dispute.

Conclusion: Navigating the Intersection of Administrative Duty and Social Realities

The Supreme Court's 1982 decision in X Ltd. v. N Ward offers a fascinating glimpse into the judiciary's attempt to balance an applicant's right to timely administrative action with an agency's perceived need to manage complex social situations and maintain public order. By acknowledging a degree of "rational administrative discretion," even in what is fundamentally a confirmatory act, particularly concerning the timing of that act, the Court opened the door for considering factors beyond the strict letter of the specific empowering statute.

While providing a pragmatic solution in a volatile local situation, the ruling also raises enduring questions about the appropriate limits of such discretion, the potential for misuse of administrative power to address issues outside an agency’s direct remit, and the balance between an individual's right to prompt administrative decisions and the broader community's interests. It remains a key case study in Japanese administrative law on the complexities of "timing discretion" and the challenges faced by public authorities operating at the dynamic intersection of legal duty and social reality.