Adherence to Drug Package Inserts: Japan's Supreme Court on Medical Standards vs. Prevailing Custom

Date of Judgment: January 23, 1996 (Heisei 8)

Case Reference: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, 1992 (O) No. 251

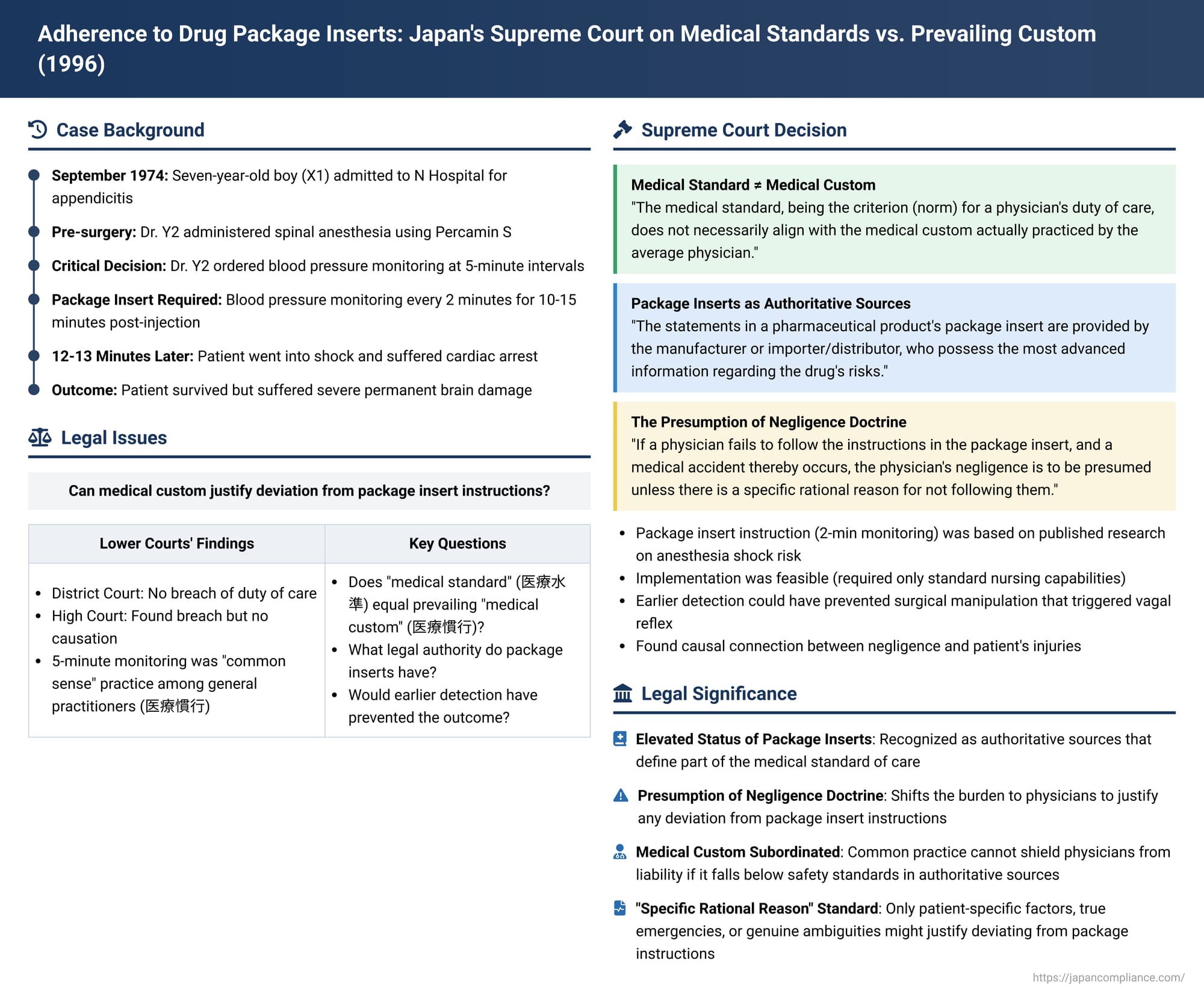

In a landmark judgment delivered on January 23, 1996, the Supreme Court of Japan provided crucial clarifications on the standard of care expected of physicians, particularly concerning their adherence to the instructions and warnings contained in pharmaceutical package inserts (能書 - nōgaki). The "Spinal Anesthesia Shock Case," as it is often known, addressed the conflict that can arise when prevailing medical custom diverges from the explicit guidance provided by drug manufacturers. The Court's decision underscored the primacy of information in package inserts in defining the appropriate medical standard, establishing a presumption of negligence if such instructions are disregarded without specific rational justification.

Factual Background: An Appendectomy and Anesthetic Tragedy

The case involved X1, a seven-year-old boy at the time of the incident in September 1974 (Showa 49). X1 was admitted to N Hospital, operated by Y1 (a medical corporation), complaining of abdominal pain and fever. He was diagnosed with appendicitis, and surgery was scheduled to be performed by Dr. Y2.

Prior to the appendectomy, Dr. Y2 administered spinal anesthesia to X1 using a drug called Percamin S. Approximately 12 to 13 minutes after the injection of the anesthetic, X1 suddenly went into a state of shock and suffered cardiac arrest. Although his life was saved, he was left with severe and permanent neurological damage due to hypoxic brain injury (脳機能低下症 - nōkinō teikashō).

X1 and his parents, X2 and X3, subsequently filed a lawsuit against the hospital operator Y1 and the physician Dr. Y2, seeking damages totaling approximately 93.98 million yen, based on claims of breach of contract or tort (medical negligence).

Lower Court Proceedings: A Focus on Medical Custom vs. Package Insert

The journey of the case through the lower courts revealed differing perspectives on Dr. Y2's duty of care:

First Instance (Nagoya District Court, judgment May 17, 1985):

The District Court dismissed the plaintiffs' claims, finding no breach of the duty of care by Dr. Y2 in relation to the medical accident.

High Court (Nagoya High Court, judgment October 31, 1991):

The High Court's findings were more nuanced. It acknowledged a critical piece of evidence: the package insert for Percamin S. This document explicitly stated in its "Side Effects and Countermeasures" section, under blood pressure management, that blood pressure should be measured once before injecting the anesthetic, and then at 2-minute intervals for 10 to 15 minutes following the injection.

Despite this clear instruction, Dr. Y2 had instructed the attending nurse to monitor X1's blood pressure at 5-minute intervals during the surgery. The High Court found that at the time of the incident (1974), monitoring blood pressure at 5-minute intervals was indeed the "common sense" practice among general practitioners. Based on this, the High Court initially concluded that, judging by the "medical standard of the time" (which it appeared to equate with this common practice), Dr. Y2 could not be deemed negligent for ordering 5-minute checks.

However, the High Court then introduced a different line of reasoning. It stated that physicians have a "natural duty" to observe the precautions detailed in the package inserts of the drugs they use. From this perspective, Dr. Y2's failure to adhere to the 2-minute monitoring interval specified in the Percamin S insert constituted a breach of his duty of care.

Despite finding a breach of duty on this ground, the High Court ultimately rejected the plaintiffs' claim due to a lack of causation. It reasoned that it was not clear whether monitoring blood pressure every 2 minutes would have enabled earlier detection of X1's deteriorating condition, especially since the collapse was sudden. The plaintiffs appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision (January 23, 1996)

The Supreme Court partially overturned the High Court's judgment, specifically regarding the liability of Y1 (the hospital operator) and Dr. Y2, and remanded this part of the case for further proceedings. (The appeal concerning another doctor involved in resuscitation efforts was dismissed). The Supreme Court's reasoning on the duty of care, medical standards, and the role of package inserts was highly significant:

1. Medical Standard as the Norm for Duty of Care:

The Court began by reaffirming its established jurisprudence (citing its decision of June 9, 1995, in the Retinopathy of Prematurity case – Case 42② in the PDF source) that the "medical standard" (医療水準 - iryō suijun) prevailing at the time of treatment serves as the benchmark for determining a physician's duty of care. It also reiterated that this medical standard is not a monolithic, nationwide absolute, but should be determined by considering various factors, including the physician's specialty, the nature of the medical institution where they practice, and the characteristics of the medical environment in the region.

2. Medical Standard vs. Medical Custom – A Crucial Distinction:

The Supreme Court then drew a critical distinction that became a cornerstone of this judgment:

"The medical standard, being the criterion (norm) for a physician's duty of care, does not necessarily align with the medical custom (医療慣行 - iryō kankō) actually practiced by the average physician. Therefore, even if a physician performs a medical act in accordance with medical custom, it cannot be immediately said that they have fulfilled their duty of care according to the medical standard."

This statement directly challenged the High Court's initial inclination to equate the "common sense" practice of general practitioners with the legally required medical standard.

3. The Authoritative Role of Pharmaceutical Package Inserts:

The Court then focused on the significance of the information provided in drug package inserts:

- Source of Highest Information: "The statements in a pharmaceutical product's package insert (能書 - nōgaki) are provided by the manufacturer or importer/distributor, who possess the most advanced information regarding the drug's risks (side effects, etc.). This information is provided for the purpose of ensuring the safety of patients receiving the drug, by conveying necessary details to the physicians and other medical professionals who will use it."

- Presumption of Negligence for Non-Adherence: This led to the Court establishing a new legal principle: "Therefore, if a physician, in using a pharmaceutical product, fails to follow the instructions for use stated in said document [the package insert], and a medical accident thereby occurs, the physician's negligence is to be presumed unless there is a specific rational reason (特段の合理的理由 - tokudan no gōriteki riyū) for not following them."

4. Application to the Percamin S Case:

Applying these principles to the specific facts, the Supreme Court found Dr. Y2 negligent:

- Clarity and Basis of the Package Insert Instruction: The package insert for Percamin S had, since 1972 (Showa 47) – two years before X1's surgery – explicitly included the instruction for 2-minute interval blood pressure monitoring for 10-15 minutes post-injection. This instruction was not arbitrary; it was based on specific research by a Dr. Kitahara, published in 1960 (Showa 35), indicating a heightened risk of spinal anesthesia shock (characterized by a sudden drop in blood pressure potentially leading to cardiac arrest) during this critical period. The purpose of frequent monitoring was precisely to detect and manage such a life-threatening side effect promptly.

- Feasibility of Adherence: The Court noted that implementing 2-minute blood pressure monitoring was not an unduly burdensome task. It did not require highly specialized knowledge or advanced technology, only the presence of a regular nurse capable of performing blood pressure measurements. There was no indication of any particular obstacle preventing Dr. Y2 from following this instruction in X1's case.

- Lack of "Rational Reason" for Deviation: Given the clear, safety-critical instruction in the package insert and the feasibility of its implementation, the Supreme Court found that Dr. Y2 had no "rational reason" for deviating from the 2-minute monitoring requirement and opting for 5-minute intervals instead.

- Medical Custom Does Not Excuse: The Court explicitly rejected the notion that the prevailing "common sense" or medical custom of 5-minute intervals among general practitioners at the time could excuse this deviation. It stated: "Even if general practitioners at that time did not follow these written precautions and considered 5-minute blood pressure monitoring to be common sense and practiced it as such, this merely describes the prevailing medical custom of the average physician at the time. Performing medical acts in accordance with such custom alone does not mean that the duty of care based on the medical standard required of a medical institution has been fulfilled." The medical standard, informed by the package insert's safety warning, demanded more.

5. Causation – Reversing the High Court:

The Supreme Court also disagreed with the High Court's finding on causation. It reasoned that X1's blood pressure had begun to drop shortly after 4:40 PM, before the acute vagal reflex was triggered by surgical manipulation (traction on the appendix) around 4:44-4:45 PM. The Court stated that had Dr. Y2 adhered to the 2-minute monitoring schedule, it was highly probable that the initial blood pressure decline and the developing hypoxia would have been detected earlier (e.g., around 4:42 PM or 4:43 PM). Such early detection would likely have led Dr. Y2 to take corrective measures and, crucially, to refrain from proceeding with the surgical manipulation that acted as a trigger for the vagal reflex, which exacerbated the shock state and led to cardiac arrest and subsequent brain damage. Therefore, the Supreme Court found a causal link between Dr. Y2's negligence (failure to ensure 2-minute monitoring) and X1's severe neurological injury.

A supplementary opinion by Justice Kabe Tsunetake strongly reinforced the majority's view, criticizing the High Court for incorrectly equating the "medical custom" of average practitioners with the normative "medical standard" that should guide the assessment of negligence. Justice Kabe emphasized that the package insert's directive for 2-minute monitoring was clear, based on medical research, and easily achievable, thus forming part of the expected medical standard for Dr. Y2.

Analysis and Implications: Elevating Package Inserts in Medical Law

The Supreme Court's decision in the "Spinal Anesthesia Shock Case" has had a profound and lasting impact on medical malpractice law and medical practice in Japan:

- Primacy of Package Inserts: This ruling significantly elevates the legal status of pharmaceutical package inserts. They are no longer just advisory documents but are recognized as containing critical safety information that forms a key component of the expected medical standard of care.

- Medical Custom Subordinated to Safety Norms: The judgment clearly establishes that prevailing medical custom cannot be used as a shield against liability if that custom falls below the standard of care dictated by authoritative sources like package inserts, especially when those inserts provide scientifically-backed safety protocols that are feasible to implement. The "average" practice does not define the "acceptable" or "legal" standard if it compromises patient safety based on known risks.

- The "Presumption of Negligence" Doctrine: The introduction of a "presumption of negligence" for deviating from package insert instructions without a "specific rational reason" is a major legal development. This effectively shifts a burden to the physician or medical institution to justify any such deviation if a patient suffers harm.

- Defining "Specific Rational Reason": While the Court found no rational reason in this instance, subsequent case law has explored what might constitute such a reason. This typically involves patient-specific factors (e.g., known allergies to alternative safer drugs, unique physiological conditions making the standard instruction harmful), true emergencies precluding strict adherence, or perhaps genuine ambiguity in the insert itself. However, mere inconvenience or adherence to a less vigilant local custom is unlikely to suffice.

- Reinforcing Physicians' Duty to Stay Informed: The decision implicitly reinforces the ongoing professional obligation of physicians to be fully aware of and understand the information provided in package inserts for the medications they prescribe and administer. This includes updates and new warnings issued by manufacturers, who hold the most comprehensive data on their products. (It's worth noting that since August 2021, paper package inserts in Japan have been largely phased out, with official drug information now primarily provided through the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) website, making access to up-to-date information even more critical).

- Impact on Medical Practice and Patient Safety: This ruling likely contributed to increased diligence among medical professionals in adhering to the guidelines in package inserts, thereby enhancing patient safety. It provides a strong legal incentive for prioritizing manufacturer's safety instructions over potentially outdated or less rigorous local customs.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1996 judgment in the Spinal Anesthesia Shock Case represents a watershed moment in Japanese medical jurisprudence. By clearly distinguishing between normative medical standards and prevailing medical customs, and by establishing the authoritative role of pharmaceutical package inserts in defining that standard, the Court significantly strengthened patient protection. The presumption of negligence for unexplained deviations from package insert instructions serves as a powerful reminder to the medical profession of their duty to prioritize patient safety by adhering to the best available information on drug administration, particularly the crucial warnings and precautions meticulously detailed by those who know the drugs best—their manufacturers. This case continues to be a vital reference point for understanding the contours of medical responsibility and the expected standard of care in Japan.