Adding New Grounds to Challenge Shareholder Resolutions: Too Late After the Deadline, Says Japan's Supreme Court

Judgment Date: December 24, 1976

Case: Action for Cancellation of Shareholders' Meeting Resolution (Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench)

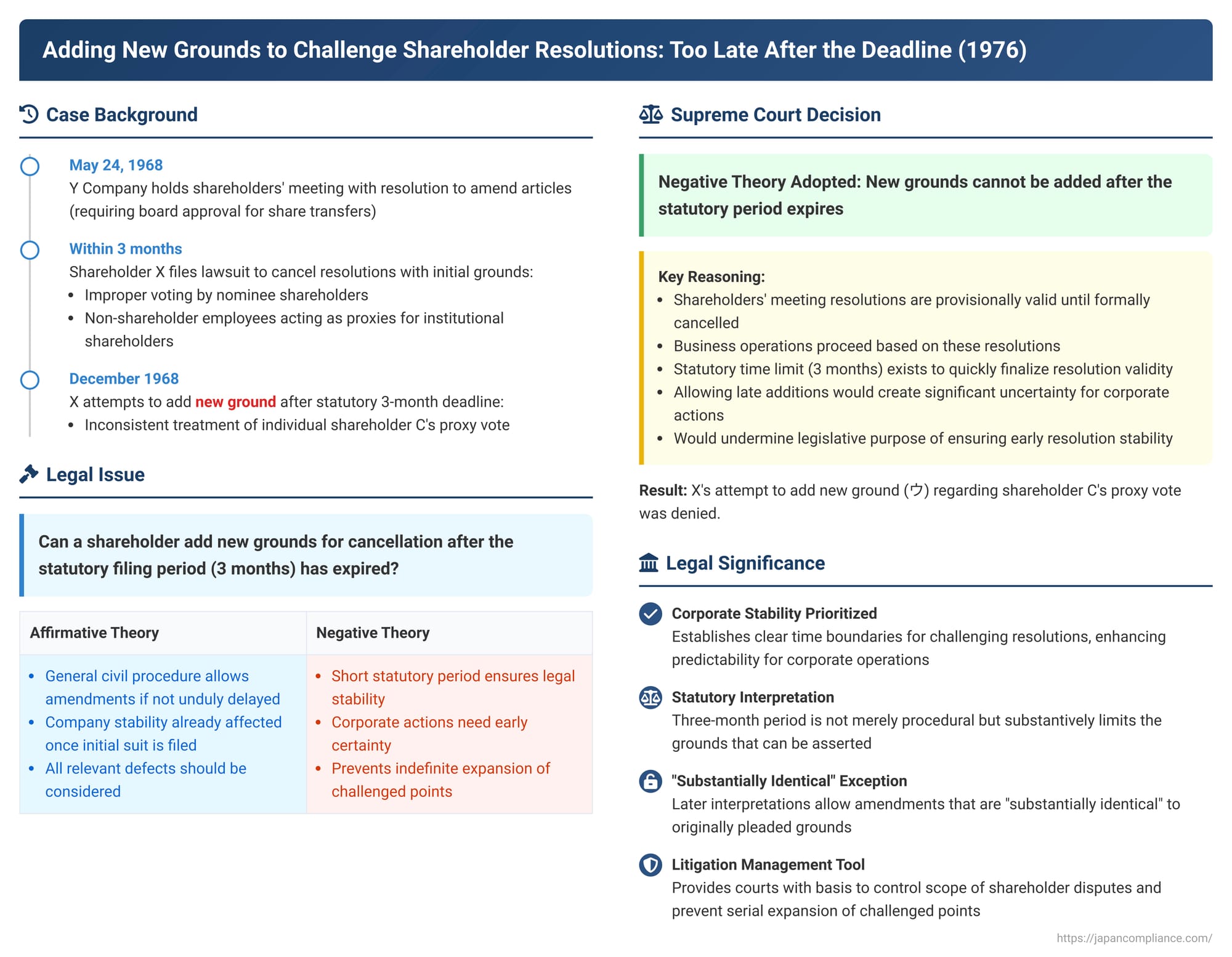

This 1976 Japanese Supreme Court decision addressed a crucial procedural question in corporate litigation: Once a shareholder has filed a timely lawsuit to cancel a resolution passed at a shareholders' meeting, can they later introduce new reasons or grounds for challenging that same resolution if the statutory deadline for initially filing the lawsuit has already passed? The Court's firm answer was no, emphasizing the need for legal stability and prompt clarification of corporate decisions.

Factual Background: A Challenged Resolution and Belated Allegations

The case involved Y Company and its shareholder, X.

- The Disputed Meeting and Initial Claims: On May 24, 1968, Y Company held a shareholders' meeting where resolutions were passed, including one to amend its articles of incorporation to require approval from the board of directors for any transfer of shares. X, a shareholder of Y Company, initiated a lawsuit to cancel these resolutions, arguing that the manner in which they were passed violated laws and the company's articles of incorporation.

X's initial allegations of defects included:- (ア) Y Company had improperly allowed registered nominee shareholders to exercise voting rights for shares that were beneficially owned by the deceased A. X contended that A's heirs (which included X) should have been recognized for voting purposes instead of the nominees.

- (イ) Y Company's articles of incorporation stipulated that only other attending shareholders could act as proxies for voting. Despite this, X alleged that non-shareholder employees were permitted to act as proxies for institutional shareholders, specifically Niigata Prefecture, Jōetsu City (both public entities), and B Corporation.

- Addition of a New Allegation: In December 1968, several months after the statutory three-month period for filing a cancellation suit had likely expired (counting from the May 24 resolution date), X sought to add a new ground for challenging the resolutions:

- (ウ) X claimed that Y Company's refusal to recognize a proxy vote for shares owned by another individual shareholder, C, was inconsistent with its allowance of non-shareholder employee proxies for the institutional shareholders mentioned in point (イ). This differential treatment, X argued, violated the principle of shareholder equality and constituted another reason for cancelling the resolutions.

The lower courts dealt with allegations (ア) and (イ). The key issue before the Supreme Court regarding this aspect of the case was the permissibility of adding allegation (ウ) after the statutory deadline.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: No New Grounds After Filing Period Expires

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal. In doing so, it laid down a clear rule regarding the addition of new cancellation grounds:

The Court held that it is not permissible for a shareholder to add new grounds for cancelling a shareholders' meeting resolution after the statutory period for filing such a suit (then three months from the date of the resolution, under Article 248(1) of the Commercial Code) has expired.

The Supreme Court provided the following rationale for this restrictive approach:

- A shareholders' meeting resolution, even if it contains defects, is treated as provisionally valid until it is formally cancelled by a court. The company's business operations proceed based on such resolutions.

- The statutory time limit for filing a cancellation suit is intended to bring clarity and certainty to the legal status of potentially flawed resolutions at an early stage.

- If shareholders were allowed to introduce new reasons for cancellation indefinitely (as long as it wasn't deemed unduly late in a general litigation sense), it would become very difficult for the company to predict whether a resolution might ultimately be overturned. This would lead to significant instability in the execution of corporate decisions.

- Allowing such late additions would undermine the legislative purpose of the short statutory filing period, which is to quickly finalize the validity of resolutions. Therefore, the statutory period must be interpreted as a limit on asserting the defects themselves.

Based on this, the Supreme Court affirmed the lower court's decision not to allow the late addition of allegation (ウ) concerning shareholder C.

(The Supreme Court also addressed allegation (イ) regarding proxy qualifications for institutional shareholders, finding that allowing employees of such entities to act as proxies, even if articles generally restrict proxies to other shareholders, was permissible. This was because these employees act under the direction of the shareholder entity, pose no risk of disrupting the meeting, and denying this would effectively disenfranchise such institutional shareholders. This part of the reasoning also supported the overall dismissal of X's appeal.)

Analysis and Implications: Prioritizing Legal Stability

This Supreme Court decision solidified the "Negative Theory" (否定説 - hitei setsu) in Japanese corporate law, which disallows the addition of new grounds for cancelling a shareholders' meeting resolution after the statutory filing period has lapsed.

1. The Nature of the Lawsuit and the Time Limit:

A lawsuit to cancel a shareholders' meeting resolution (now governed by Article 831(1) of the Company Law, which maintains the three-month limit) is considered to have a single object of litigation (sosho-butsu), even if multiple defects are alleged. Therefore, adding a new ground is viewed as an amendment to the existing claim, not the filing of a new lawsuit. The core issue is how the purpose of the strict three-month time limit should influence the permissibility of such amendments.

2. Arguments for the "Negative Theory" (Disallowing Late Additions):

The primary justification, as emphasized by the Supreme Court, is legal stability. Companies need to be able to rely on their resolutions and proceed with business. Allowing new challenges to surface long after the fact would create uncertainty. Proponents also argue that the three-month period is generally sufficient for diligent shareholders to identify and articulate any alleged defects in a resolution.

3. Arguments for the "Affirmative Theory" (Allowing Late Additions):

Conversely, proponents of allowing later additions question whether company law needs to impose stricter limits on amending claims than general civil procedure rules (which generally permit amendments if they are not overly delayed and do not unfairly prejudice the other party). They argue that once a cancellation suit is filed within the statutory period, the company's legal stability is already somewhat compromised, and the marginal benefit of preventing later additions of grounds might not outweigh the plaintiff shareholder's interest in having all relevant defects considered by the court.

4. Impact of Subsequent Civil Procedure Reforms:

Later reforms in Japanese civil procedure aimed at promoting speedier trials and earlier clarification of legal and factual issues (e.g., through enhanced preparatory proceedings and planned trial schedules) share some of the underlying goals of the Negative Theory (i.e., early issue identification). However, it's debatable whether these general procedural improvements strengthen or weaken the case for the Negative Theory in the specific context of company law; proponents of the Affirmative Theory might argue that robust general procedures make specific restrictive interpretations of the Company Law less necessary.

5. Practical Considerations in Cancellation Suits:

Shareholder resolution cancellation suits are sometimes filed in the context of internal management disputes or, historically, were used as harassment tactics by so-called "special shareholders" (sokaiya). In such situations, plaintiffs might be inclined to raise a multitude of alleged defects, sometimes serially. The Negative Theory provides courts with a tool to manage the scope of litigation and prevent an indefinite expansion of disputed points. Given that shareholders' meetings can be complex, and many aspects could potentially be challenged, requiring plaintiffs to clearly state all factual bases for their nullification claim at the outset is arguably reasonable.

6. The Nuance of "Substantial Identity":

Even under the generally accepted Negative Theory, it has long been understood that amendments or clarifications that are "substantially identical" to the originally pleaded grounds may still be permissible after the three-month period. More recent interpretations suggest a potentially broader allowance if the core factual basis of the dispute was evident in the initial claim, even if the specific legal characterization or additional facts are introduced later.

For instance, one lower court case (later referenced by commentators as consistent with a more flexible approach even under the Negative Theory) allowed an additional claim where the overarching theme of the lawsuit was the company's unfair management of the meeting, even though the newly added defect was of a different legal type than initially pleaded. Another case permitted an added assertion that a company's explanation at a meeting was factually false, deeming it closely related to an initial claim of failure to provide an adequate explanation. Conversely, attempting to add a claim that a different shareholder was a conflicted party, when the original claim only identified another specific shareholder as conflicted, was disallowed even if a "conflicted party" claim was part of the initial suit. The key determinant often seems to be how the court perceives the "core of the dispute" and whether the new allegation introduces a fundamentally new factual basis or merely a different legal perspective on already presented facts.

7. The Court's Finding on Proxy Qualifications for Institutional Shareholders:

Separately, but also relevant to the overall dismissal of X's appeal, the Supreme Court addressed X's allegation (イ) concerning proxy voting. It upheld the High Court's view that when shareholders are public entities like prefectures or cities, or other corporations, it is permissible for their employees to act as their proxies at a shareholders' meeting, even if the company's articles of incorporation generally limit proxies to "attending shareholders." The rationale was that such employees are acting under the direction and control of the shareholder entity, represent the shareholder's will, and do not pose a risk of disrupting the meeting in the way an unrelated third party might. Denying this right would, in practice, make it very difficult for such institutional shareholders to exercise their voting rights and have their views reflected in resolutions.

Conclusion: Ensuring Promptness and Certainty in Corporate Litigation

The 1976 Supreme Court decision firmly established that new grounds for seeking the cancellation of a shareholders' meeting resolution cannot be introduced after the statutory three-month period for initiating such a lawsuit has passed. This rule underscores the strong emphasis in Japanese corporate law on achieving legal stability and ensuring that the validity of corporate actions can be determined promptly. While this promotes certainty for companies in their ongoing operations, the nuanced possibility of amending claims that are "substantially identical" to those initially pleaded provides a narrow avenue for adjustments. The judgment also offered a pragmatic interpretation regarding the ability of employees to represent institutional shareholders as proxies, facilitating their participation in corporate governance.