Accounting in Flux: When Can Bank Directors Be Criminally Liable for Financial Statements in Japan? A Supreme Court Analysis

Case: Criminal Action for Violation of Securities and Exchange Act and Commercial Code

Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Judgment of July 18, 2008

Case Number: (A) No. 1716 of 2005

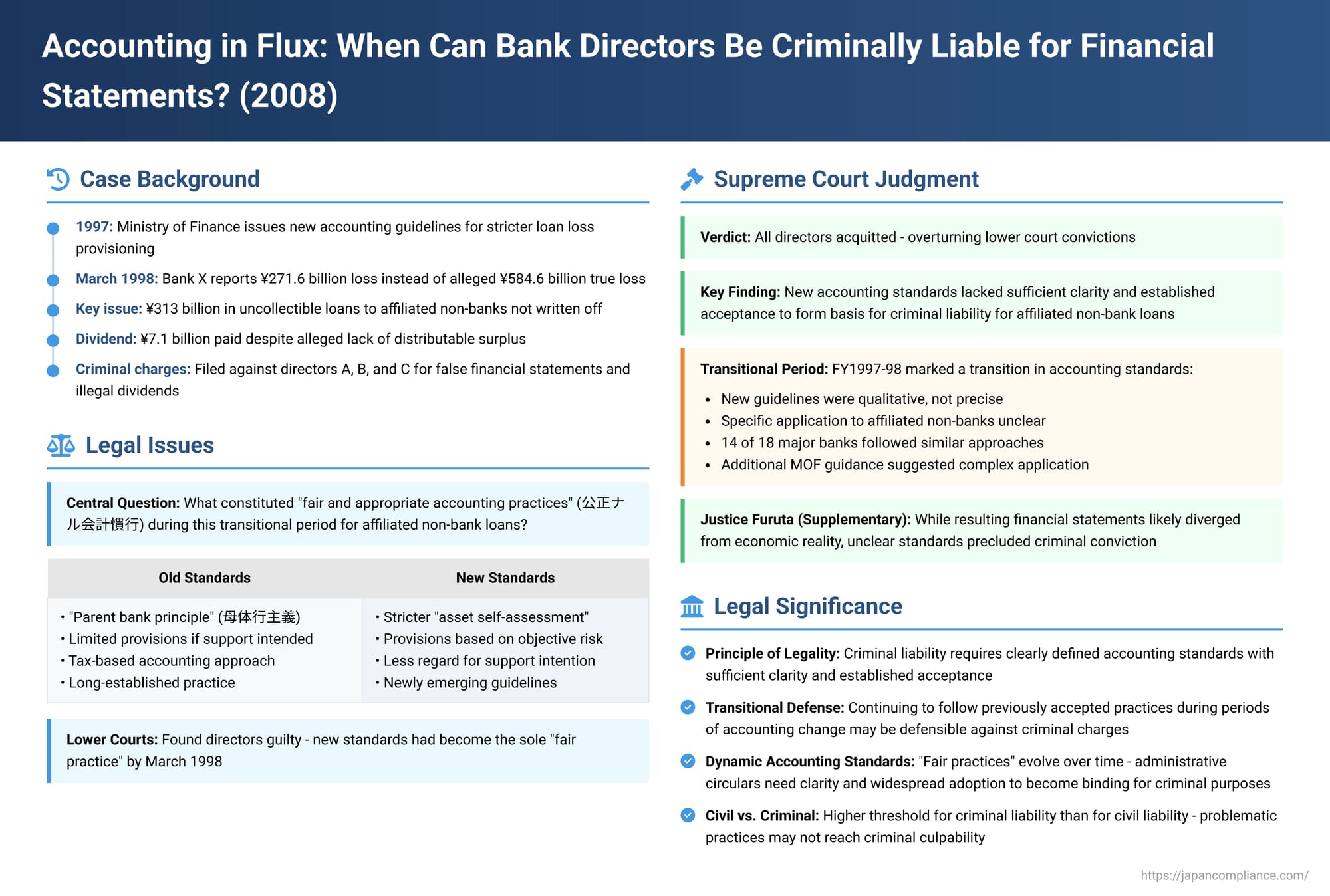

The integrity of financial reporting is a cornerstone of investor confidence and market stability. Directors of companies, especially banks, bear a heavy responsibility for ensuring that financial statements accurately reflect the company's financial position. But what happens when accounting standards themselves are in a state of flux, with new regulatory guidance emerging that may not be entirely clear or uniformly adopted across an industry? A landmark Japanese Supreme Court decision on July 18, 2008, addressed this very issue in the context of criminal charges brought against former representative directors of a major bank for allegedly submitting false financial statements and making illegal dividend payments during such a transitional period. The Court's acquittal of the directors hinged on its finding that the new accounting standards lacked sufficient clarity at the time to form the basis for criminal liability.

The Banking Crisis and Accounting Under Pressure: Facts of the Case

The defendants, A, B, and C, were former representative directors of Bank X. They faced criminal charges relating to Bank X's financial statements for the fiscal year ending March 1998. The prosecution alleged that:

- False Financial Statements: The directors had failed to make adequate write-offs or provisions for uncollectible loans amounting to approximately 313 billion yen. This, it was claimed, resulted in the bank understating its current net loss for the fiscal year. The prosecution asserted that the true net loss was approximately 584.6 billion yen, but it was reported as a much smaller 271.6 billion yen in the bank's securities report filed with the authorities. This constituted a violation of the Securities and Exchange Act for filing a securities report containing false statements on important matters.

- Illegal Dividend Payments: Despite allegedly having no distributable surplus (due to the understated losses), the directors were accused of proposing and securing shareholder approval for a dividend payment totaling approximately 7.1 billion yen (3 yen per share), by improperly drawing down voluntary reserves. This was alleged to be an illegal dividend payment in violation of the Commercial Code.

The core of the dispute lay in the interpretation and application of "fair and appropriate accounting practices" (公正ナル会計慣行 - kōsei naru kaikei kankō), particularly concerning loan loss provisioning for loans made to "affiliated non-bank financial institutions" (関連ノンバンク - kanren non-banku).

- Old Accounting Standards (Pre-1997/98 Changes): Traditionally, Japanese banks, in making provisions for bad loans, often followed accounting practices aligned with what was permissible for tax deductions. A key aspect was the "parent bank principle" (母体行主義 - botaikō shugi). Under this principle, if a bank expressed an ongoing intention to support an affiliated non-bank (often a subsidiary or closely related finance company), it would generally not make significant write-offs or provisions for loans to that affiliate, even if the affiliate was struggling. This approach was reflected in the "Settlement Accounting Standards" contained within a "Basic Matters Circular" issued by the Ministry of Finance (MOF), which regulated banks.

- New Accounting Standards (Emerging around 1997): The mid-1990s saw several financial institutions fail in Japan, prompting a push for greater transparency and soundness in bank accounting. The MOF spearheaded reforms:

- It urged financial institutions to conduct rigorous "asset self-assessment" (自己査定 - jiko satei) based on their own established criteria to determine the true quality of their loan portfolios.

- The MOF's "Asset Valuation Circular" (issued by the Banking Bureau in March 1997) emphasized that banks needed to make necessary write-offs and provisions even for borrowers they intended to continue supporting, if an objective assessment indicated a high probability of that borrower's future bankruptcy.

- In July 1997, the MOF Banking Bureau Director-General issued further circulars that formally amended the "Settlement Accounting Standards." These revised standards, which incorporated the principles of stricter self-assessment, were to be applied from the fiscal year ending March 1998.

- Various industry bodies, like the Japanese Bankers Association and the Japanese Institute of Certified Public Accountants (JICPA), also issued Q&As and practice guidelines to help banks implement these new approaches.

- Bank X's Accounting Treatment for FY Ending March 1998:

For its financial statements for the year ending March 1998, Bank X developed its own internal rules for asset self-assessment. However, for its loans to affiliated non-bank financial institutions, these internal rules effectively permitted an accounting treatment that was much closer to the old standards. Specifically, the bank largely avoided making significant write-offs or provisions for these affiliated non-bank loans, primarily on the grounds that it intended to continue providing financial support to these entities. This approach, while arguably deviating from the spirit and direction of the new MOF guidelines, was defended by the bank as a permissible interpretation during a transitional period when the new standards, particularly their application to the uniquely treated affiliated non-banks, lacked complete clarity and widespread, uniform adoption.

Lower Courts' Convictions: Strict Adherence to New Standards Demanded

The Tokyo District Court and subsequently the Tokyo High Court found defendants A, B, and C guilty on both charges. These lower courts held that by the time Bank X was preparing its financial statements for the fiscal year ending March 1998, the new accounting standards (i.e., the revised Settlement Accounting Standards as supplemented by the Asset Valuation Circular and related guidelines) had already become the sole prevailing "fair and appropriate accounting practice." They concluded that Bank X's adherence to older, more lenient methods for its affiliated non-bank loans constituted a deliberate violation of these established fair practices, leading to false financial statements and, consequently, illegal dividend payments.

The Supreme Court's Acquittal: New Standards Lacked Sufficient Clarity for Criminal Liability

The Supreme Court overturned the convictions by the lower courts and acquitted all three defendants (A, B, and C).

Reasoning of the Apex Court: The "Clarity" Test for Fair Accounting Practices in a Transitional Period

The Supreme Court's decision hinged on its assessment of the prevailing accounting standards at the specific time (March 1998) and particularly their applicability to loans to affiliated non-banks:

- New Standards Were Qualitative and Lacked Specificity for Affiliated Non-Banks: The Court found that the new accounting standards, while emphasizing more rigorous self-assessment by financial institutions, were largely qualitative in nature, providing broad guidelines rather than precise, quantitative criteria that could be uniformly and immediately applied across all situations. This lack of specificity was particularly pronounced concerning the treatment of loans to affiliated non-bank financial institutions. These entities had historically been treated differently under the "parent bank principle." The new guidelines did not offer sufficiently clear, concrete, or measurable rules on how to assess and provision for these specific types of loans in a way that entirely displaced the older, established practices.

The Court noted that the MOF itself had issued further administrative communications (such as a non-publicly disclosed "April 1997 Administrative Contact") concerning affiliated non-banks, suggesting that the application of the new, stricter self-assessment principles to these entities was complex and perhaps not as rigidly mandated as for ordinary borrowers. The Court concluded that actual asset valuation for these loans under the new qualitative guidelines was "not easy." - A Period of Transition in Accounting Practices: The Supreme Court characterized the period around the March 1998 fiscal year-end as one of transition in bank accounting standards. It was not yet unequivocally clear or universally understood within the banking industry that the older, tax-law-influenced approach for valuing loans to affiliated non-banks was entirely impermissible and that the new, more stringent self-assessment standards had to be strictly and immediately applied to them for the purpose of criminal law.

- No Immediate Illegality in Following Prior Accepted Practices (for these specific loans under criminal law scrutiny): Given this lack of definitive clarity and the transitional nature of the accounting environment at that specific time, the Supreme Court determined that Bank X's decision to use an accounting treatment for its affiliated non-bank loans that was largely consistent with previously accepted "fair accounting practices" (i.e., the tax-law based approach factoring in ongoing parental support) could not be deemed immediately or unequivocally illegal for the purposes of establishing criminal liability. Even if this approach deviated from the general direction of the new MOF guidelines, the new guidelines themselves lacked the requisite precision and established acceptance with regard to these specific types of loans to serve as a clear basis for criminal charges.

- Widespread Similar Practices Among Other Banks: The Court also took note of the fact that many other major Japanese banks, in their financial statements for the same March 1998 period, had also not fully provided for anticipated future support losses to their affiliated non-bank institutions in the strict manner implied by the newest guidelines. For instance, of 18 major banks, 14 (including Bank X) had not set aside provisions for future support losses to affiliated non-banks. This widespread practice indicated a lack of uniform understanding and application of the new, less precise standards across the industry at that time, further supporting the view that these standards had not yet solidified into the sole binding "fair accounting practice" for these specific types of loans.

Justice Furuta's Supplementary Opinion: Justice Furuta, in his supplementary opinion, reinforced the majority's reasoning. He particularly emphasized the historical context of the "parent bank principle" and the inherent difficulty in deeming loans to affiliated non-banks (to whom continued financial support was pledged) as definitively uncollectible under the then-prevailing tax-based accounting norms. He noted that while the new MOF guidelines aimed for greater objectivity, the specific guidance for affiliated non-banks was not sufficiently clear or binding at that point to criminalize Bank X's accounting treatment for these loans. Justice Furuta did acknowledge, however, that Bank X's resulting financial statements likely presented a picture that diverged significantly from the underlying economic reality of its loan portfolio, which, while not meeting the threshold for criminal conviction given the unclear accounting standards, was nonetheless problematic from a financial disclosure and transparency standpoint.

Analysis and Implications: Defining "Fair Accounting Practices" in Law

This 2008 Supreme Court judgment is of considerable importance, as it was the first time the Court directly addressed the interpretation of "fair and appropriate accounting practices" (as referenced in the then-Commercial Code Article 32, Paragraph 2, and now implicitly required by Companies Act Article 431 and the Company Calculation Rules Article 3) in a criminal proceeding, especially concerning the normative weight of administrative circulars.

- Administrative Circulars and "Fair Accounting Practices":

A key takeaway is that the Supreme Court did not deny the possibility that administrative circulars, such as the MOF's "Settlement Accounting Standards," could serve as evidence of, or indeed constitute, "fair accounting practices." The pivotal issue in this case was not whether circulars can have such status, but whether the new circulars and guidelines at that specific point in time (FY 1997/98) had achieved sufficient clarity, established acceptance, and practical applicability—especially for complex situations like loans to affiliated non-banks—to render adherence to previously accepted practices criminally unlawful.

This raises important considerations from the perspective of the principle of legality in criminal law (罪刑法定主義 - zaikei hōtei shugi), which demands that criminal prohibitions be clearly defined. If vague or ambiguously evolving administrative guidance were to become the basis for criminal prosecution without a high degree of certainty and foreseeability, it would undermine this fundamental legal principle. The Supreme Court, by acquitting the directors, appeared sensitive to this, effectively requiring a high threshold of clarity and establishedness before a new accounting practice (particularly one derived from administrative guidance rather than direct legislation or definitive professional accounting standards) could be considered the sole binding "fair practice" for criminal law purposes, especially when it represented a departure from long-standing prior practices. - The "Transitional Period" as a Defense:

The Court's emphasis on the "transitional period" was crucial. When accounting standards are undergoing significant change, directors and companies that continue to rely on previously accepted and understood practices may have a valid defense against criminal charges of intentional or grossly negligent false accounting, particularly if the new standards are complex, lack detailed application guidance for specific scenarios, or have not yet achieved widespread and uniform understanding and implementation within the relevant industry. - "Fair and Appropriate Accounting Practices" – A Dynamic Concept:

The concept of "generally accepted accounting principles" or "fair and appropriate accounting practices" is not static; it evolves with changes in business complexity, financial instruments, and societal expectations for transparency. In Japan, the sources for these practices include the Companies Act itself, the detailed Company Calculation Rules (a Ministry of Justice ordinance), and, very importantly, "generally accepted corporate accounting standards and other corporate accounting practices."

For listed companies, accounting standards promulgated by the Accounting Standards Board of Japan (ASBJ)—which was established after the events in this case—and, where adopted, International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), now play a paramount role. For unlisted companies, the framework can be somewhat more varied.

This Supreme Court case occurred during a period when the MOF's administrative circulars held very significant sway in bank accounting. The judgment suggests that for a new accounting method introduced via such guidance to displace an older, established practice and become the sole legally binding "fair practice" (especially for purposes of criminal law), it must be demonstrably clear, well-understood by practitioners, and practically implementable. Significant ambiguity or a lack of uniform adoption during a transitional phase can preclude a finding of criminal intent or gross negligence if directors followed a previously accepted method, even if that method is later seen as less aligned with the ultimate goals of the new guidance. - Distinction between Civil and Criminal Liability:

It is important to remember that this was a criminal case. The Supreme Court acquitted the directors of criminal charges. On the very same day, it also issued a decision in a related civil case, dismissing an appeal by different plaintiffs who were seeking to hold these same directors civilly liable for illegal dividend payments. The Tokyo High Court had already found the directors not liable in that civil case, and the Supreme Court upheld that outcome.

Generally, the standard of proof and the level of culpability required for criminal liability (often requiring specific intent, or at least a high degree of recklessness for certain financial offenses) are higher than for establishing civil liability for breach of a director's duty of care (which can be based on simple negligence). Justice Furuta's supplementary opinion highlighted this by noting that while Bank X's accounting practices at the time might not have met the threshold for criminal illegality due to the lack of clarity in the prevailing accounting standards for affiliated non-bank loans, they were nonetheless highly problematic from the perspective of financial transparency and likely presented a picture that diverged significantly from the bank's true economic condition. - The Post-Judgment Accounting Landscape:

Since the events of this case and the 2008 Supreme Court judgment, the landscape of accounting standard-setting in Japan has evolved considerably. The role of the ASBJ has become central, and accounting standards (especially for listed companies and financial institutions) are now much more detailed, formalized, and often aligned with international norms. This has reduced the kind of ambiguity regarding "fair accounting practices" that was at the heart of the Bank X case. However, the underlying principles articulated by the Supreme Court – particularly the need for clarity and established acceptance of an accounting standard before it can form the basis for severe sanctions like criminal liability, especially during transitional periods – remain pertinent for any emerging or highly specialized accounting issues that may not yet be covered by definitive, universally accepted standards.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's acquittal of the former Bank X directors on July 18, 2008, was a significant decision that underscored the importance of clarity and established practice in the application of accounting standards, particularly when criminal liability is at stake. The Court found that during the transitional period in question (the fiscal year ending March 1998), the new, stricter accounting guidelines for loan loss provisioning, especially as they pertained to complex situations like loans to affiliated non-bank financial institutions, lacked the requisite clarity and uniform adoption across the banking industry to render the defendants' adherence to previously accepted (albeit less conservative) practices criminally culpable. This judgment highlights a crucial aspect of the rule of law: for "fair and appropriate accounting practices," particularly those derived from evolving administrative guidance, to form the basis of criminal sanctions, they must be sufficiently clear, well-understood, and unequivocally applicable, leaving little room for reasonable alternative interpretations or reliance on established prior norms. While emphasizing financial transparency, the ruling also acknowledged the challenges faced by corporate management when navigating periods of significant regulatory and accounting change.