Accountability in Public Spending: Japan's "Senketsu" System and Official Liability

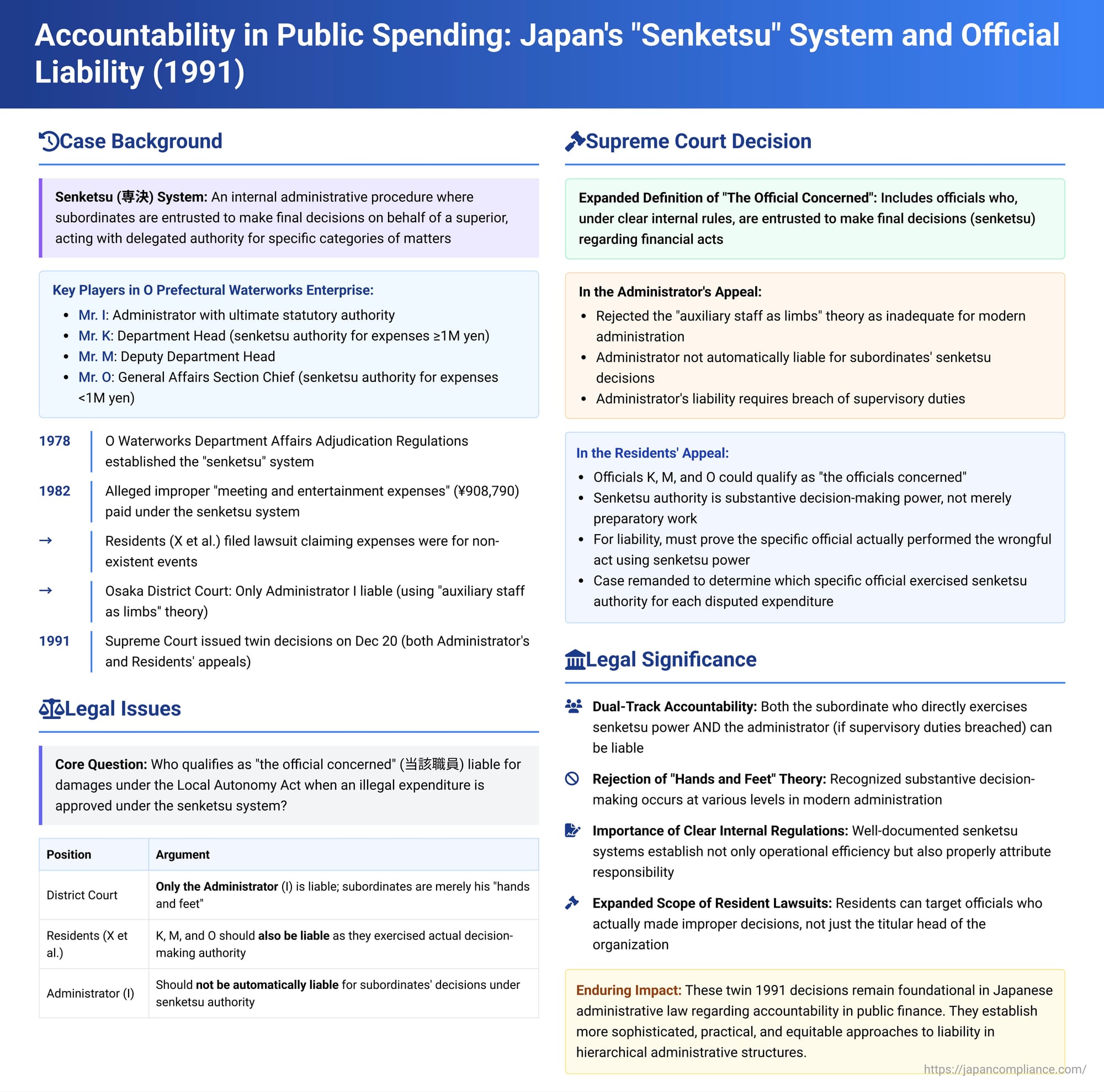

Ensuring that public funds are spent legally and responsibly is a cornerstone of good governance. When such funds are misused, determining who bears financial responsibility within a complex administrative structure can be challenging. Two landmark rulings by the Supreme Court of Japan on December 20, 1991, shed considerable light on this issue, particularly concerning a system of entrusted decision-making known as "senketsu." These cases, arising from allegedly improper entertainment expenses at a local public water utility, clarified who qualifies as "the official concerned" liable for damages under Japan's Local Autonomy Act.

The Factual Background: A Dispute Over Entertainment Expenses

The controversy centered around the O Prefectural Waterworks Enterprise, a local public entity established under Japan's Local Public Enterprise Act to manage water services for O Prefecture. Several key figures within its administration became central to the ensuing legal battle:

- Mr. I: The Administrator of the O Prefectural Waterworks Enterprise, the highest-ranking official with ultimate statutory authority over its operations and finances.

- Mr. K: The Head of the O Waterworks Department, a senior manager within the Enterprise.

- Mr. M: The Deputy Head of the O Waterworks Department.

- Mr. O: The General Affairs Section Chief within the O Waterworks Department.

A critical element of the Enterprise's internal governance was its "senketsu" (専決) system, detailed in the O Waterworks Department Affairs Adjudication Regulations (a 1978 directive). In Japanese administrative practice:

- "Kessai" (決裁) refers to the final decision-making authority, typically vested in the head of an organization, such as the Administrator (Mr. I).

- "Senketsu," as defined by these internal regulations, allowed designated subordinate officials to routinely make such final decisions on behalf of the Administrator for specific categories of matters, effectively acting with final authority for those items.

The Adjudication Regulations structured "senketsu" authority for budget execution based on the monetary amount involved. For instance, matters involving expenditures of one million yen or more (with some exceptions) were subject to the "senketsu" of the Department Head (Mr. K). For expenditures under one million yen, including conference and entertainment expenses, the General Affairs Section Chief (Mr. O) held "senketsu" authority.

The legal dispute was triggered by residents of O Prefecture (referred to as Plaintiffs X et al.). They alleged that several payments categorized as "meeting and entertainment expenses," made on May 31, 1982, were for non-existent events and therefore constituted illegal expenditures of public funds. These included:

- An expenditure of 230,420 yen at a venue identified as "Restaurant Y."

- Various other meeting and entertainment expenditures totaling 678,370 yen, detailed in an attachment to the first-instance court judgment.

The plaintiffs initiated a "resident lawsuit" under the provisions of Article 242-2, Paragraph 1, Item 4 of the Local Autonomy Act (as it existed at the time). This type of lawsuit allows residents to sue officials on behalf of the local government to recover damages caused by illegal financial acts. The suit targeted Administrator I, Department Head K, Deputy Department Head M, and General Affairs Section Chief O, seeking recovery of the total alleged illegal expenditure of 908,790 yen for O Prefecture.

The Journey Through the Lower Courts

The case first went before the Osaka District Court, which issued a mixed judgment:

- Claim regarding "Restaurant Y": This portion of the claim was dismissed outright. The court found that the plaintiffs had failed to satisfy a crucial procedural prerequisite: filing a resident audit request with the prefectural auditors concerning this specific expenditure before initiating the lawsuit.

- Claims against K, M, and O: These claims were also dismissed. The District Court reasoned that only the Administrator (Mr. I) possessed the ultimate legal authority for expenditures. Even if K, M, or O processed decisions under the "senketsu" system, they were not considered "the officials concerned" (当該職員 - tōgai shokuin) subject to liability under the Local Autonomy Act in this specific context. The court viewed their authority as not being a formal delegation that would make them primarily liable; they were merely auxiliary to the Administrator.

- Claim against Administrator I: For the non-"Restaurant Y" expenditures (the 678,370 yen), the District Court found Administrator I liable. The court applied a concept known as the "auxiliary staff as limbs" theory (補助職員手足論 - hojo shokuin teashi ron). Under this theory, the official who actually handled the "senketsu" for the problematic expenditures (in this instance, likely General Affairs Section Chief O for many items) was seen as merely acting as the "hands and feet" of Administrator I. Since the court found that I knew the expenditures were illegal, he was held directly responsible for the actions of his subordinates who were merely executing his will.

Both Plaintiffs X et al. (regarding the dismissals) and Administrator I (regarding his liability) appealed the District Court's decision. The Osaka High Court, however, upheld the lower court's judgment in its entirety, leading to further appeals to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Twin Decisions of December 20, 1991

The appeals culminated in two significant, related decisions by the Supreme Court's Second Petty Bench on the same day.

A. The Administrator's Appeal (Related Case)

In a decision concerning Administrator I's appeal against his liability (Case No. Heisei 2 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 137, as widely understood from legal commentaries on these rulings), the Supreme Court took a different stance from the lower courts on the basis of a superior's liability:

- Rejection of the "Auxiliary Staff as Limbs" Theory: The Supreme Court moved away from the "auxiliary staff as limbs" theory. It found this theory inadequate for complex administrative organizations where substantive decision-making occurs at various levels.

- Administrator as "The Official Concerned": The Court affirmed that the Administrator (Mr. I), as the official holding original statutory authority, clearly falls within the definition of "the official concerned."

- Liability in "Senketsu" Cases: Crucially, the Court ruled that when a "senketsu" system is properly established through internal regulations, the Administrator is not automatically or vicariously liable for illegal financial acts committed by a subordinate who is exercising "senketsu" authority. Instead, the Administrator's liability would arise only if there was a breach of their duty of command and supervision. This means plaintiffs would need to prove that the Administrator, through intent or negligence, failed to prevent the subordinate's illegal act (e.g., by having a faulty "senketsu" system, inadequate oversight, or by knowing of and not stopping the wrongdoing).

- Nature of "Senketsu": The Court recognized "senketsu" as a legitimate internal administrative procedure. The subordinate entrusted with "senketsu" is considered to be making their own decision within the scope of the authority granted to them.

- Outcome: Based on this reasoning, the part of the judgment holding Administrator I liable under the "hands and feet" theory was overturned, and his case was remanded for re-examination, presumably to assess whether he had breached his supervisory duties.

B. The Residents' Appeal (Supreme Court Case No. Heisei 2 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 138)

This judgment directly addressed the appeal by Plaintiffs X et al. regarding the dismissal of their claims concerning the "Restaurant Y" expenditure and the non-liability of auxiliary officials K, M, and O.

1. The "Restaurant Y" Expenditure:

The Supreme Court upheld the lower courts' dismissal of the claim related to the 230,420 yen expenditure at "Restaurant Y." The reasoning was straightforward: the plaintiffs' failure to first request a resident audit for this specific item, as required by the Local Autonomy Act, rendered the subsequent lawsuit on this point procedurally defective and inadmissible. This reaffirmed the strict nature of this prerequisite for resident lawsuits.

2. Liability of Auxiliary Officials K, M, and O for the Other Expenditures (678,370 yen):

This was the most groundbreaking part of the ruling. The Supreme Court overturned the lower courts' decision that had dismissed the claims against Department Head K, Deputy Head M, and General Affairs Section Chief O on the grounds that they were not "the officials concerned."

- Redefining "The Official Concerned" (当該職員 - tōgai shokuin):

The Court began by referencing an earlier precedent (Supreme Court, April 10, 1987) which stated that "the official concerned" broadly includes:The Court then significantly expanded this definition in the context of "senketsu." It declared that "the official concerned" also encompasses an official who, based on clear internal organizational rules (such as a formal directive or "kunrei"), is entrusted by the person with original statutory authority (like the Administrator) to make the final decision ("senketsu") regarding the financial accounting act.The rationale for this expansion was that an official exercising "senketsu" is not merely engaged in a mechanical preparatory act but is, in fact, making the ultimate internal decision on the matter, albeit on behalf of the Administrator. If internal rules clearly empower them to do so routinely, they are exercising a form of decision-making power that carries responsibility. The Court noted that the substantive right to claim damages or return of unjust enrichment, which residents exercise on behalf of the local government, can be based on general civil law principles or Article 243-2, Paragraph 1 of the Local Autonomy Act (which deals with officials' liability for causing financial loss).- Those who originally hold statutory authority for the financial accounting act in question.

- Those who have come to possess such authority through means such as delegation.

- Application to Officials K, M, and O:

The Court then examined the facts:Given these internal rules, the Supreme Court concluded that Department Head K, Deputy Head M, and General Affairs Section Chief O could indeed be "the officials concerned" for the allegedly illegal expenditures, as their positions were designated with "senketsu" authority over such matters. They were empowered to make the final internal decision.- The O Prefectural Waterworks Enterprise was a local public enterprise, and its Administrator (Mr. I) held statutory authority for its financial affairs, akin to the head of a local government.

- The O Waterworks Department Affairs Adjudication Regulations (a 1978 directive) and the O Prefectural Waterworks Enterprise Management Regulations (a 1964 regulation) laid out the procedures for expenditures, including those for conference and entertainment. These regulations established a "senketsu" system.

- Specifically, for conference/entertainment expenses, the "senketsu" authority was vested in the Department Head (K), Deputy Department Head (M), or the General Affairs Section Chief (O), depending on the expenditure amount and other criteria (e.g., expenses under one million yen for the General Affairs Section Chief). These officials were designated to routinely make the final decision on behalf of the Administrator.

- Important Caveat on Actual Conduct:

The Court carefully added a crucial qualification: merely holding a position that possesses "senketsu" authority does not automatically translate into liability. For a damages claim against such an official to succeed, it must be proven that the specific official actually performed the wrongful financial accounting act in question—for example, by approving a known illegal expenditure using their "senketsu" power. If an official with "senketsu" authority was not actually involved in the decision-making for a particular illicit payment, they would not be liable for it. - Outcome for this Part of the Appeal:

The Supreme Court reversed the part of the High Court judgment that had affirmed the dismissal of claims against K, M, and O concerning the 678,370 yen in expenditures. The first-instance judgment on this point was also overturned. This portion of the case was remanded to the Osaka District Court for further proceedings. The District Court was instructed to re-examine the claims against K, M, and O, determining:- Which specific official(s) among K, M, and O actually exercised "senketsu" authority for each of the disputed illegal expenditures.

- Whether those actions, undertaken with "senketsu" authority, constituted illegal financial conduct that caused financial loss to O Prefecture.

Analysis and Implications of the Rulings

These twin Supreme Court decisions of December 20, 1991, had profound implications for Japanese administrative law and the accountability of public officials:

- Clarification of "Senketsu" and Liability: The rulings provided vital legal clarification on the nature of "senketsu." It was not to be viewed as mere assistance or preparatory work but as a genuine form of entrusted final decision-making power when properly established by internal rules. Consequently, the official exercising "senketsu" could be held directly and personally liable for their own wrongful decisions made under that authority.

- Rejection of the "Hands and Feet" Doctrine: The Supreme Court decisively moved away from the simplistic "auxiliary staff as limbs" (hojo shokuin teashi ron) theory for determining a superior's liability. This signaled a more sophisticated understanding of modern administrative structures, where substantive decision-making responsibilities are often distributed across various hierarchical levels.

- Dual-Track Accountability: The decisions effectively established a potential dual track for financial accountability in "senketsu" scenarios:

- The Subordinate Official: The official who directly and wrongfully exercises "senketsu" power for an illegal expenditure can be held personally liable for the financial loss caused by their act.

- The Superior Official (e.g., Administrator): The superior who holds ultimate statutory authority can also be held liable, but not automatically for the subordinate's act. The superior's liability hinges on a breach of their own duties of command and supervision—specifically, if they intentionally or negligently failed to prevent the subordinate's wrongful act. This is a liability for their own failing as a supervisor, distinct from vicarious liability for the subordinate's decision itself.

- Importance of Clear Internal Regulations: The case underscored the critical importance of having clear, formal internal regulations ("kunrei," directives, etc.) that properly define lines of authority, responsibility, and the scope of any "senketsu" powers. A well-documented and procedurally sound "senketsu" system is essential not only for operational efficiency but also for correctly attributing responsibility.

- Impact on Resident Lawsuits: By broadening the interpretation of "the official concerned" to include those exercising "senketsu," the Supreme Court expanded the potential range of defendants in resident lawsuits. This allowed residents seeking to recover public funds to more directly target the individual official who actually made the improper decision, even if that official was not the titular head of the organization. This interpretation was based on the Local Autonomy Act's provisions at the time; subsequent amendments to the Act (e.g., in 2002) further refined the framework for such lawsuits, shifting the focus regarding "the official concerned" more directly to the question of who bears substantive liability, rather than just defendant eligibility.

- Broader Significance for Public Administration: The principles laid down in these rulings reinforced the concept of individual accountability within public organizations. They provided a more nuanced and realistic legal framework for assessing liability in hierarchical structures where decision-making authority is necessarily distributed. The judgments implicitly recognized the independent judgment and responsibility that comes with being entrusted with "senketsu" powers.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's decisions on December 20, 1991, in the O Prefectural Waterworks Enterprise case were pivotal moments in the development of Japanese administrative law concerning public finance. They offered a significantly refined understanding of liability for improper public expenditures, especially within administrative systems that employ the common Japanese practice of "senketsu."

By formally acknowledging the substantive decision-making role of officials exercising "senketsu" and by carefully delineating the distinct basis for a supervisor's liability (rooted in supervisory duty rather than automatic imputation), the Court established a more sophisticated, practical, and equitable approach to accountability. These principles remain highly relevant for ensuring responsible governance, upholding the integrity of public financial management, and ensuring that individuals entrusted with public decision-making, at any level, are answerable for their actions.