Accountability in Outsourced Public Functions: Suing the City for a Private Body's Building Confirmation

Decision Date: June 24, 2005

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

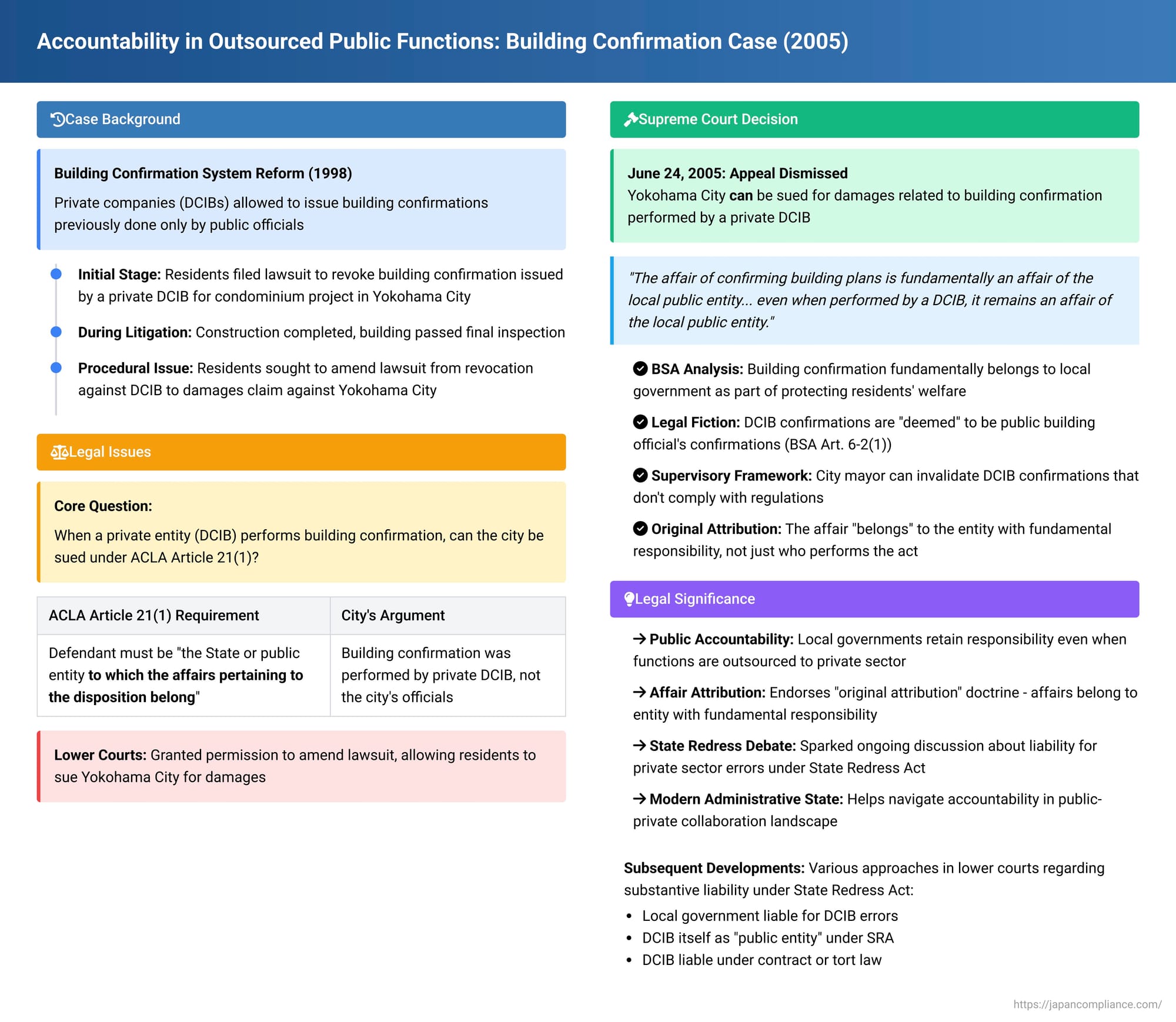

When public functions are delegated to private entities, who is ultimately accountable if things go wrong? A 2005 Japanese Supreme Court decision explored this question in the context of building confirmations, a critical step in Japan's construction approval process. The Court addressed whether a city could be sued for damages following a building confirmation issued by a privately-owned "Designated Confirmation and Inspection Body" (DCIB), particularly when the initial lawsuit sought to revoke the private body's action. This case sheds light on the legal responsibilities that remain with local governments even when specific tasks are outsourced.

The Building Plan, the Private Confirmation, and a Shift in Legal Strategy

The case originated with residents living near a proposed large-scale condominium project in Yokohama City ("Y City"). These residents challenged a building confirmation (an official verification that a building plan complies with the Building Standards Act and related regulations) that had been issued for the project. Notably, this confirmation was not issued by the city's public building official (kenchiku shuji) but by a private entity, "the Company," operating as a Designated Confirmation and Inspection Body (DCIB). The residents initially filed a lawsuit seeking the revocation of this building confirmation, naming the DCIB as the defendant.

However, a common challenge in such lawsuits arose: during the litigation, the condominium project was completed, and the building passed its final inspection. Under Japanese administrative law, this typically means that a lawsuit seeking only to revoke the initial building confirmation loses its "legal interest" (uttae no rieki), as the act of construction is complete and revocation alone offers no practical remedy.

Facing this situation, the residents sought the court's permission to amend their lawsuit. They proposed to change their claim from a revocation suit against the DCIB to a claim for monetary damages against Y City. This type of amendment is potentially allowed under Article 21, Paragraph 1 of Japan's Administrative Case Litigation Act (ACLA), which permits changing a suit for the revocation of an administrative disposition to a related damages claim if certain conditions are met. The lower courts granted permission for this change. Y City, however, contested this, appealing to the Supreme Court. The City's core argument was that it did not qualify as "the State or a public entity to which the affairs pertaining to the said disposition or administrative determination belong," the crucial criterion under ACLA Article 21(1) for allowing such a change of defendant in a damages claim.

The Supreme Court's Green Light for Suing the City

The Supreme Court, in its decision on June 24, 2005, dismissed Y City's appeal, thereby upholding the lower courts' permission to amend the lawsuit. The Court's reasoning centered on the interpretation of the Building Standards Act (BSA) and the underlying nature of the building confirmation affair:

1. Building Confirmation: Fundamentally a Local Government Affair

The Supreme Court began by analyzing the BSA's provisions. It noted that Article 6(1) of the BSA requires a building owner to obtain a confirmation from a public building official that their plan complies with building regulations. This requirement, the Court reasoned, stems from the local public entity's broad responsibility to promote residents' welfare, including protecting their lives, health, and property. Therefore, the affair of confirming building plans is fundamentally an affair of the local public entity, and the administrative subject to which this affair belongs is the local public entity where the public building official is established.

2. DCIBs: Operating Under City Supervision

The BSA, through amendments allowing for private sector involvement, creates a system where DCIBs can also issue these confirmations. Crucially, BSA Article 6-2(1) states that when a DCIB issues a confirmation and a confirmation certificate, that confirmation is deemed to be a confirmation by the public building official, and the certificate is deemed to be the public building official's certificate.

Furthermore, the BSA establishes a supervisory framework:

- DCIBs must report the issuance of confirmation certificates to the "specified administrative agency" (特定行政庁 - tokutei gyōsei chō), which, for areas with a public building official like Y City, is the city's mayor (BSA Art. 6-2(3), now Art. 6-2(5)).

- If the specified administrative agency, upon receiving such a report, determines that a plan confirmed by a DCIB does not actually comply with building regulations, it must notify the building owner and the DCIB. In such an instance, the DCIB's confirmation certificate loses its validity (BSA Art. 6-2(4), now Art. 6-2(6)). This provision explicitly grants the specified administrative agency the authority to rectify a DCIB's confirmation.

Based on these provisions, the Supreme Court concluded that the BSA, while allowing DCIBs to perform confirmation tasks, does so under the premise that these are fundamentally local government affairs conducted under the supervision of the specified administrative agency.

3. City as the Responsible "Public Entity" for Litigation Purposes

Given this framework, the Supreme Court held that the affair of building confirmation, even when performed by a DCIB, remains an affair of the local public entity. The administrative subject to which this affair "belongs" is the local public entity that has the authority (through its public building official) to conduct such confirmations.

Therefore, Y City was indeed "the public entity to which the affairs pertaining to the said disposition...belong" for the purposes of ACLA Article 21(1). The Court also found that, considering the Company (the DCIB) performed the confirmation under the supervision of Y City's mayor and other circumstances of the case, it was "appropriate" to permit the change of the revocation suit against the DCIB to a damages claim against Y City.

Unpacking the Decision: Implications and the Broader Legal Landscape

This Supreme Court decision carries significant implications for how accountability is structured when public duties are outsourced to private entities.

The 1998 Building Standards Act Reform: A New Era of Private Involvement

The case itself is a product of a 1998 amendment to the Building Standards Act (Act No. 100 of 1998). This reform was a key example of deregulation and the opening up of previously public-sector functions to private participation. It allowed private companies, upon receiving designation, to become DCIBs and perform building confirmation tasks, issuing legally recognized confirmation certificates (BSA Art. 6-2).

ACLA Article 21: Connecting Revocation Suits to Damages Claims

Article 21 of the Administrative Case Litigation Act serves a practical purpose: it allows a plaintiff who initially sought to revoke an administrative act to change their claim to one for damages (or other related relief) if, for example, the original claim becomes moot (as in this case, due to the building's completion). This enables the continued use of evidence and arguments already presented in court, provided the change is deemed "appropriate" and the "basis of the claim" remains fundamentally the same. The key challenge here was that the original defendant was a private DCIB, while the new defendant for the damages claim was the city. The Supreme Court's decision affirmed that such a change can be appropriate, focusing on the underlying nature of the administrative affair rather than just the identity of the initial actor.

Supervisory Powers: The Link Between the City and Private Confirmations

While some legal commentators have pointed out that the day-to-day supervision by specified administrative agencies over DCIBs might be limited (e.g., concrete review documents are not always transmitted with the DCIB's report, and a full re-review of every DCIB confirmation is not practically envisioned ), the Supreme Court found the statutory supervisory and corrective powers vested in Y City's mayor to be a sufficient link. The existence of an administrative appeal route for building confirmations under the BSA (Article 94), which the plaintiffs in this case had reportedly utilized by appealing to Y City's Building Review Council before initiating their court action, likely also played a role in the Court’s assessment of the city's involvement and the appropriateness of the lawsuit's amendment.

The "Original Attribution" of Affairs Doctrine

The Supreme Court's reasoning aligns with a particular perspective on how to determine to which entity an administrative affair "belongs." There are generally two views: (a) the affair belongs to the entity whose agency or official actually performs the act, or (b) it belongs to the entity to which the authority for that affair originally or fundamentally pertains. This decision leans towards the latter perspective. Even though the DCIB (a private company) performed the confirmation, the underlying affair of ensuring building standards is considered a local government responsibility. This is consistent with older case law concerning "agency-delegated functions," where affairs handled by local government heads on behalf of the national government were deemed to "belong" to the State for similar litigation purposes. Legal commentaries also generally support the idea that ACLA Article 21 does not permit changing a suit to one against a private individual if they are not the State or a public entity to which the affair properly belongs.

Ripple Effects: The Ongoing Debate on Liability for Private Sector Errors (State Redress Act)

While the 2005 Supreme Court decision directly addressed the procedural question under ACLA Article 21, it has fueled a broader and ongoing debate about substantive liability under the State Redress Act (SRA) when DCIBs make errors. The SRA (Article 1) makes the State or a public entity liable for damages caused by the unlawful exercise of public power by public officials. Several distinct lines of argument and judicial approaches have emerged in lower courts since the 2005 ruling:

- Local Government Directly Liable under SRA for DCIB's Errors: Some court decisions have held that the local public entity to which the building confirmation affair fundamentally belongs can be held liable under SRA Article 1 for errors committed by a DCIB. This approach is thematically consistent with the Supreme Court's 2005 decision on the attribution of affairs.

- Local Government Liable for its Own Officials' Negligence: Liability may also attach to the local government if its own public building officials are found to have been negligent, for example, in their supervisory duties over DCIBs.

- DCIB Itself as a "Public Entity" under SRA: A notable lower court ruling found a DCIB itself liable as a "public entity" under SRA Article 1. The reasoning was that the DCIB system effectively transferred the subject performing confirmation duties to the private sector, and DCIBs exercise public power independently while collecting their own fees.

- DCIB Liable under Contract Law: Other cases have found DCIBs liable to the building owner (their client) based on breach of contract, specifically a failure to exercise due care in performing their inspection and confirmation services. This contractual approach might absolve the local government of SRA liability if the fault lies exclusively with the DCIB.

- DCIB Liable under General Tort Law (Civil Code Art. 709): At least one decision held a DCIB liable under general tort law, explicitly stating that the 2005 Supreme Court ruling (on ACLA Art. 21) did not mean DCIBs are considered entities exercising public power for SRA liability purposes, thereby limiting the 2005 decision's scope in the SRA context.

Academic discourse continues to grapple with these theories, particularly whether DCIBs should be considered "public entities" for SRA purposes (either jointly with or instead of the local government), the implications for recourse actions (e.g., whether the "gross negligence" standard for recourse against public officials applies to DCIB employees), and the adequacy of mechanisms like mandatory liability insurance for DCIBs.

Conclusion: Accountability in an Evolving Public Service Landscape

The Supreme Court's 2005 decision is a landmark in navigating the complexities of administrative accountability when public functions are delegated to private bodies. By affirming that the fundamental responsibility for building confirmations remains with the local government—even when the task is performed by a private DCIB—the Court ensured that citizens have a viable path to seek redress from the public entity ultimately overseeing these critical safety-related affairs. This ruling underscores that outsourcing tasks does not necessarily mean outsourcing ultimate accountability. The subsequent rich debate and varied case law concerning the State Redress Act further illustrate the ongoing efforts within the Japanese legal system to adapt traditional notions of public liability to a modern administrative state characterized by increasing public-private collaboration and delegation.