Accident from Within? Japanese Supreme Court on Vomit Aspiration and 'External Accident' in Insurance

Date of Judgment: April 16, 2013

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Case No. 1043 (Ju) of 2011 (Accident Insurance Benefit Claim Case)

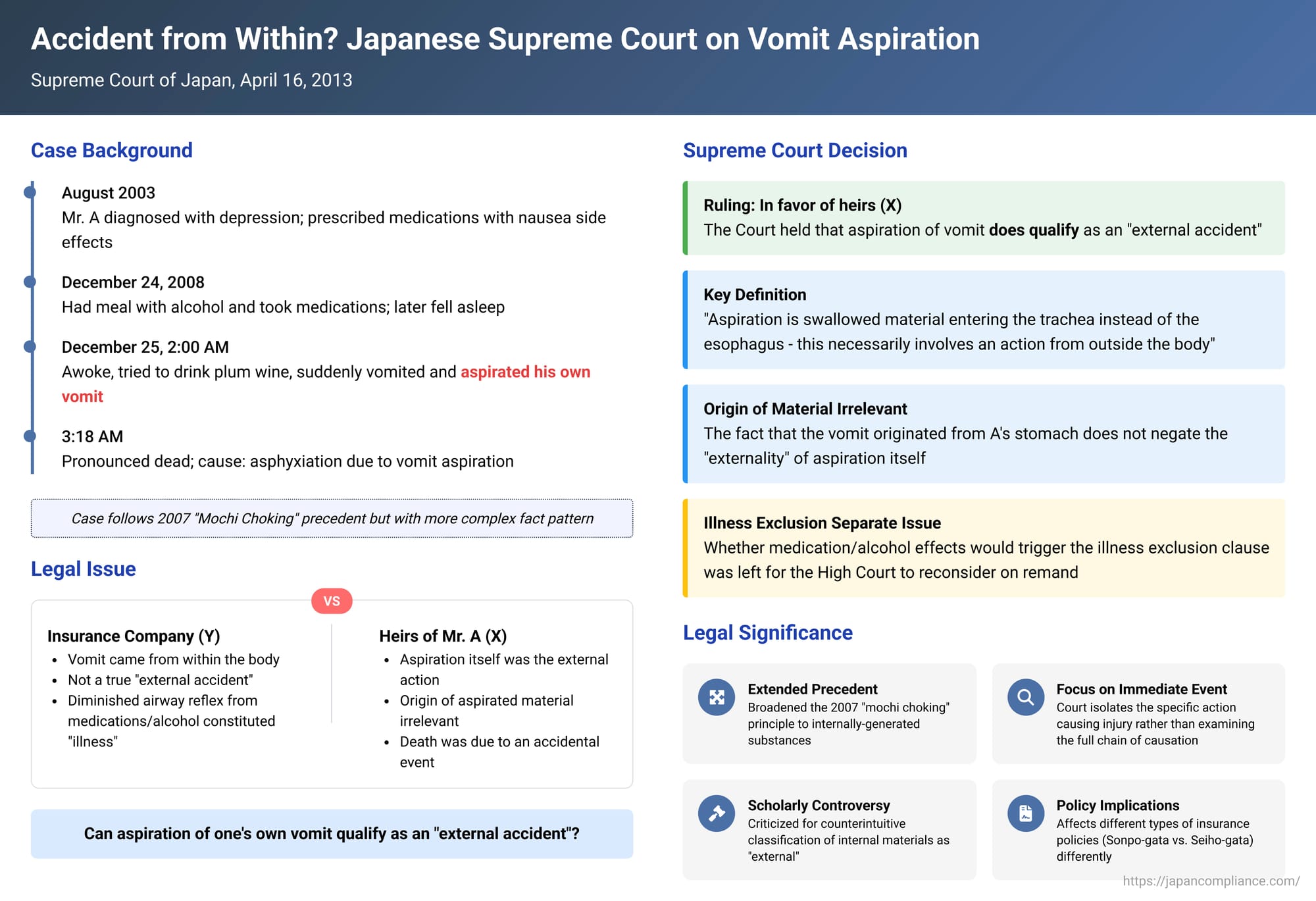

Accident insurance policies are designed to cover injuries resulting from "accidents." A key definitional element is often that the accident must be "external" in nature. While this seems straightforward for incidents like a fall or a traffic collision, it becomes far more complex when the chain of events leading to injury involves bodily processes. A particularly challenging scenario arises when an individual chokes on their own vomit, leading to injury or death. Is this an "external accident" covered by insurance, or an internal event excluded from coverage? The Supreme Court of Japan tackled this very issue in a noteworthy decision on April 16, 2013.

The Fatal Episode: Facts of the Case

Mr. A was insured under an ordinary accident insurance contract with Y Insurance Company (the defendant and respondent). The policy defined a covered event as "injury sustained by the insured due to a sudden, accidental, and external accident" (急激かつ偶然な外来の事故 - kyūgeki katsu gūzen no gairai no jiko). It also contained an exclusion clause stating that the insurer would not pay for injuries caused by "the insured's brain disorder, illness, or mental derangement".

Mr. A was receiving treatment for conditions including depression. He was prescribed several medications, some of which had known side effects of nausea and vomiting, and these effects could be amplified by alcohol consumption. On December 24, 2008, Mr. A had a meal that included alcoholic beverages and subsequently took his prescribed medications. Later, he dozed off.

Around 2:00 AM on December 25, 2008, Mr. A awoke. As he attempted to take a sip of umeshu (plum wine) on the rocks, he suddenly vomited into his own oral cavity. Due to a markedly diminished airway reflex at the time, he aspirated the vomit (i.e., inhaled it into his airway instead of expelling it or swallowing it into the esophagus). He gasped, collapsed, and lost consciousness. Mr. A was rushed to a hospital by ambulance but was pronounced dead before arrival, at 3:18 AM. The cause of death was determined to be asphyxiation due to the aspiration of vomit. It was noted that the diminished airway reflex was likely due to the central nervous system suppression and reduced sensory and motor functions caused by the alcohol and medications he had ingested hours earlier.

Mr. A's statutory heirs, X1, X2, and X3 (the plaintiffs and appellants), filed a claim with Y Insurance Company for the death benefits under the accident insurance policy. Y Insurance Company denied the claim, arguing that the incident did not qualify as an "external accident."

The Kobe District Court (first instance) initially ruled in favor of the claimants. However, the Osaka High Court (second instance) reversed this decision. The High Court reasoned that an "external accident" for insurance purposes does not include accidents caused by bodily changes or malfunctions that result from the ingestion or internal invasion of substances like drugs, alcohol, viruses, or bacteria. Since A's asphyxiation was caused by a severely diminished airway reflex, which in turn was due to the effects of the alcohol and medication he had ingested, the High Court concluded that the asphyxiation was not directly caused by an external action and therefore did not constitute an "external accident" under the policy terms. The heirs then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Policy Wording and the Central Legal Question

The case turned on the interpretation of "external accident" in the context of the policy's terms:

- Coverage Clause: The insurer pays for injury sustained by the insured due to a "sudden, accidental, and external accident." [cite: 1]

- Exclusion Clause: The insurer does not pay for injury caused by the insured's "brain disorder, illness, or mental derangement." [cite: 1]

The central question for the Supreme Court was whether the aspiration of one's own vomit, leading to asphyxiation, could be classified as an "external accident."

The Supreme Court's Reversal: Aspiration of Vomit IS an "External Accident"

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings. The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Building on Precedent (The "Mochi Choking" Case): The Court began by referencing its own earlier decision from July 6, 2007 (Minshu Vol. 61, No. 5, p. 1955; the "mochi choking" case, h103.pdf in the provided documents)[cite: 1]. In that 2007 case, the Court had held that an "external accident," based on its literal wording, means an accident caused by an action or force originating from outside the insured's body[cite: 1].

- Identifying the "Accident": The Supreme Court stated that under the policy terms, the "accident" which triggers coverage is one that results in bodily injury to the insured[cite: 1]. In the present case, the event that directly led to A's asphyxiation and death was the aspiration of vomit[cite: 1]. This aspiration, therefore, was the "accident" to be evaluated[cite: 1].

- Aspiration as an "External Action": The Court then defined aspiration as "swallowed material entering the trachea instead of the esophagus"[cite: 1]. It reasoned that such an event necessarily involves an action from outside the body and should be considered as caused by such an action[cite: 1]. The rationale here is that the material, even if originating from the stomach, is "swallowed" (or rather, re-enters the airway) from the pharynx/oral cavity, which is a space contiguous with the external environment.

- Vomit as the Aspirated Material Does Not Negate Externality: Crucially, the Supreme Court held that this conclusion—that aspiration is an external accident—remains valid even if the substance causing the airway obstruction and asphyxiation was vomit, which had originated from the insured's own stomach[cite: 1]. The act of aspiration itself is deemed "external."

- Illness Exclusion is a Separate Matter: The Supreme Court's decision focused solely on whether the aspiration event met the "external accident" requirement. It did not rule on whether an underlying illness or the effects of medication/alcohol (which might have caused the vomiting or diminished airway reflexes) would ultimately lead to the claim being denied under the separate illness exclusion clause. That determination was left for the High Court to consider upon remand[cite: 1].

Justice Tahara Mutsuo, in a supplementary opinion, elaborated that aspiration, according to general medical terminology, refers to liquid or solid matter that should pass from the oral cavity via the pharynx to the esophagus instead entering the trachea during swallowing. He stated that aspiration itself is an external accident, and the origin of the aspirated material (whether ingested food, vomit, or material from within the oral cavity like blood or broken teeth) is irrelevant to this determination[cite: 1].

Unpacking the Rationale: What Makes it "External"?

The Supreme Court's reasoning in this 2013 case is consistent with its 2007 "mochi choking" precedent. It isolates the immediate physical event causing the injury (the act of aspiration) and analyzes whether that event involves an "action from outside the body."

- The Court effectively views the pharynx and oral cavity as a conduit to the "outside," even for substances that may have briefly been internal (like stomach contents that are then vomited). The "accident" is the misdirection of material from this conduit into the airway.

- The preceding causes—why Mr. A vomited (e.g., due to medication, alcohol, or an underlying illness) or why his airway reflexes were diminished—are not considered part of the "external accident" analysis itself. Instead, these factors become relevant when assessing the applicability of the separate illness exclusion clause, for which the insurer bears the burden of proof.

Scholarly Reactions and Ongoing Debate

This decision has generated considerable discussion and, indeed, criticism among legal scholars in Japan[cite: 2].

- Criticism of "Externality" of Vomit Aspiration: Many find it counterintuitive to classify the aspiration of one's own vomit as an "external" event[cite: 2]. The argument is that the injurious agent (vomit) originated from within the insured's body, even if it was then expelled and re-entered a different bodily passage. This is contrasted with the 2007 "mochi choking" case, where the mochi was unequivocally an external object from the outset[cite: 2].

- Alternative Scholarly Approach (Comprehensive Evaluation): Some scholars propose an alternative framework for determining "externality." They suggest that instead of focusing solely on the very last event (aspiration), courts should comprehensively evaluate the entire chain of events leading to the injury and determine if the dominant or primary cause in that sequence can be considered external[cite: 2]. Following this approach, one might argue in Mr. A's case that the ingestion of medication and alcohol (external factors) was the primary trigger for the entire sequence (vomiting, diminished reflexes, aspiration), thus affirming externality through a different analytical path[cite: 2]. Such an approach might aim to limit the perceived broadness of the Supreme Court's textual focus on the aspiration event itself[cite: 2].

- The Court's Textual Focus vs. Process Evaluation: The Supreme Court's judgment, however, appears to adhere to a more direct, textual interpretation, identifying the "accident" as the aspiration itself and then assessing if that specific event involved an external action[cite: 1, 2]. This is distinct from a broader evaluation of the entire causal process leading up to the aspiration[cite: 2]. By doing so, the Court maintains consistency with the 2007 ruling's structural separation of the "external accident" requirement (claimant's burden) and the "illness exclusion" (insurer's burden).

Implications for Different Policy Types (Sonpo-gata vs. Seiho-gata)

The policy in this case was of a type typically issued by property and casualty insurers in Japan (損保型 - Sonpo-gata), characterized by a general definition of "external accident" coupled with a separate illness exclusion clause[cite: 2]. The Supreme Court's reasoning in both the 2007 and 2013 cases heavily relied on this "wording and structure"[cite: 2, 3].

A question remains regarding the applicability of this line of reasoning to accident insurance policies or riders typically issued by life insurance companies (生保型 - Seiho-gata). Historically, Seiho-gata policies often defined "external accident" by explicitly including exclusionary language within the definition itself—e.g., stating that "external" means not caused by illness or other internal bodily factors[cite: 2]. Some older Seiho-gata policies also required the accident to be one listed in a specific, official catalog of accident types, though this practice has largely been discontinued[cite: 2].

If the policy language itself incorporates "absence of illness" into the definition of "external," a strict application might suggest that the claimant bears the burden of proving this absence as part of their main case. However, some legal scholars argue that the substantive rationale of the 2007 Supreme Court decision—particularly its aim to appropriately allocate and potentially lessen the claimant's burden of proof regarding illness—should ideally extend to Seiho-gata policies as well[cite: 3]. This could be achieved by interpreting the exclusionary phrases within the Seiho-gata definition of "external" not as part of the claimant's primary proof, but effectively as an exclusion clause for which the insurer would still bear the evidentiary burden[cite: 3]. There is a discernible trend in academic commentary towards seeking a more unified interpretation of coverage for similar risks, despite variations in policy wording across different types of insurers[cite: 3].

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's 2013 decision on death by vomit aspiration further refines the judicial understanding of what constitutes an "external accident" in Japanese accident insurance law. By focusing on the act of aspiration itself as involving an "action from outside the body"—even when the aspirated substance is the insured's own vomit—and by separating this from the issue of whether an underlying illness triggered the event (which is a matter for the illness exclusion clause), the Court maintained a line of reasoning consistent with its 2007 precedent on choking.

This ruling, while providing a clear directive on the specific facts, has sparked significant academic debate. Critics question the conceptualization of aspirating internally-generated matter as "external," while others seek to interpret the decision in a way that allows for a more holistic assessment of causation. The decision underscores the inherent challenges in applying general insurance policy terms to the often complex and medically nuanced circumstances of human injury and death, and it highlights the ongoing efforts to achieve both doctrinal consistency and equitable outcomes in insurance disputes. The case also implicitly points to the importance of precise policy drafting by insurers and the careful scrutiny of such terms by courts and consumers alike.