Academic Publication vs. Pharmaceutical Promotion: Japan's Supreme Court Clarifies Advertising Law

Date of Decision: June 28, 2021

Case Reference: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, 2018 (A) No. 1846

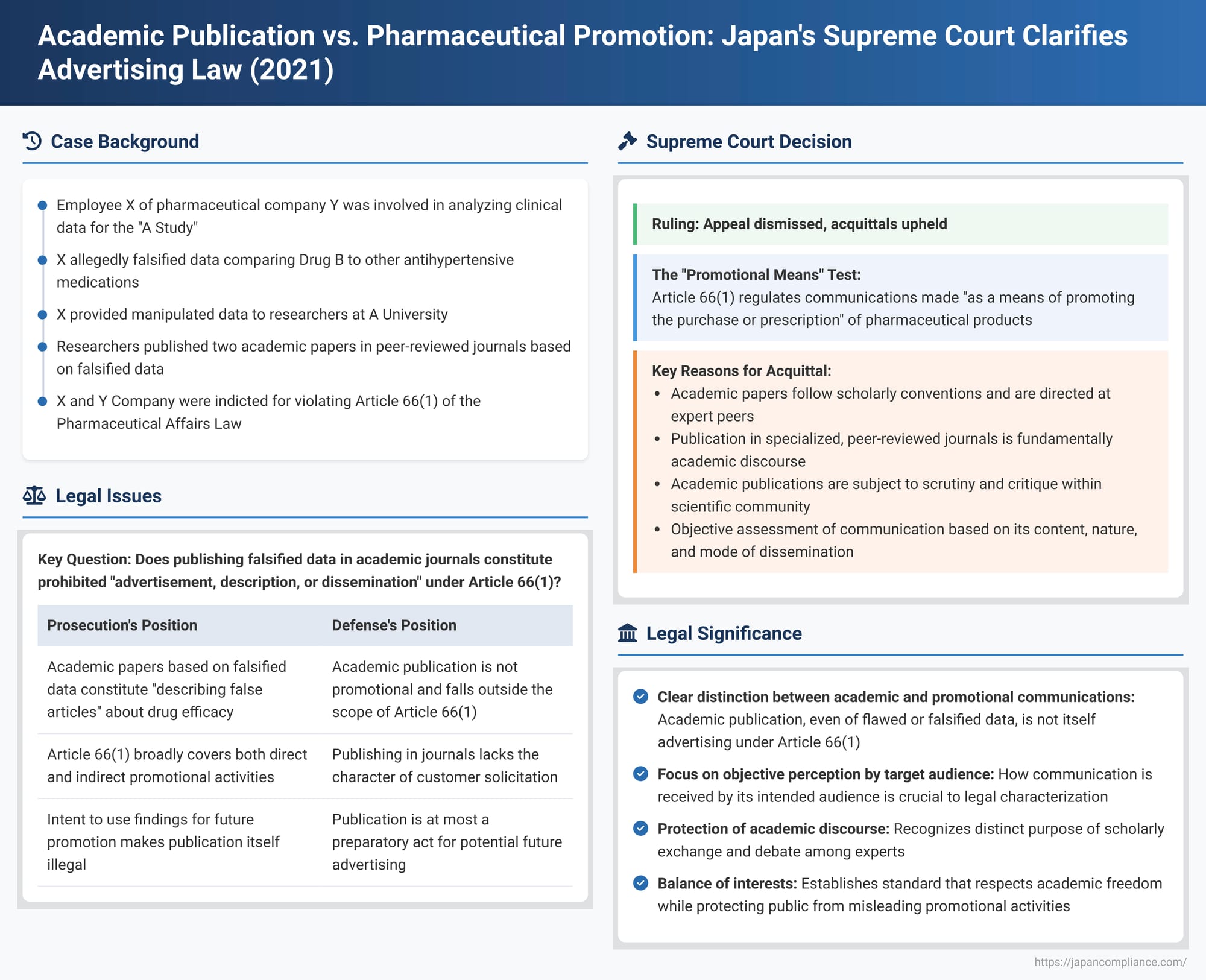

In a significant decision issued on June 28, 2021, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed the complex intersection of academic research, pharmaceutical marketing, and the scope of drug advertising regulations. The case involved a pharmaceutical company employee accused of violating Japan's (former) Pharmaceutical Affairs Law by contributing to the publication of academic papers based on falsified clinical trial data. The Supreme Court's ruling provides crucial clarification on what constitutes prohibited "advertisement, description, or dissemination" of false or exaggerated claims about pharmaceuticals, particularly distinguishing scholarly communications from direct promotional activities.

The Factual Matrix: A Clinical Trial, Falsified Data, and Academic Publications

The case centered around Mr. X, an employee of Y Company, a pharmaceutical manufacturer and distributor. Y Company produced Drug B, a treatment for hypertension. Mr. X was involved in analyzing clinical data for a study known as the "A Study," which was conducted by medical researchers at A University. The A Study aimed to compare the efficacy of Y Company's Drug B against other antihypertensive medications in terms of suppressing cardiovascular events, such as strokes.

The prosecution alleged that Mr. X, in connection with his duties at Y Company and with the intent to use the findings in the company's advertising materials, falsified data derived from a sub-analysis of the A Study. He then allegedly provided this manipulated data to the researchers involved in the A Study. Subsequently, these researchers, relying on the falsified data supplied by Mr. X, published two academic papers in scholarly journals.

As a result, Mr. X and Y Company (under corporate liability provisions) were indicted for violating Article 66, Paragraph 1 of Japan's former Pharmaceutical Affairs Law (prior to its 2013 amendment, now the Act on Securing Quality, Efficacy and Safety of Products Including Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices, or PMD Act). The specific charge was that they had "described" false articles concerning the efficacy or effects of Drug B. Article 66, Paragraph 1 of the then-law stipulated: "No person shall advertise, describe, or disseminate false or exaggerated statements regarding the name, manufacturing method, efficacy, effect, or performance of pharmaceuticals, quasi-pharmaceutical products, cosmetics, or medical devices, whether explicitly or implicitly."

The Journey Through Lower Courts: Defining "Description" and "Advertisement"

The case navigated through the lower courts, with both the District Court and the High Court acquitting the defendants, albeit with detailed interpretations of the law.

First Instance (Tokyo District Court, judgment March 16, 2017):

The Tokyo District Court interpreted the scope of "advertisement" under Article 66, Paragraph 1 in a broad sense. It defined such an advertisement as an act of widely informing the public as a means of soliciting customers (which, for prescription drugs, includes physicians' motivation to prescribe) and intending to arouse or enhance their purchasing motivation.

Applying this definition, the District Court found that the act of submitting the academic papers (containing the falsified data) and having them published in scholarly journals did not fall under the category of "describing... an article" as prohibited by Article 66, Paragraph 1. The court reasoned that this act, in itself, did not possess the character of a means to solicit customers in the way commercial advertising does. Consequently, Mr. X and Y Company were acquitted.

High Court (Tokyo High Court, judgment November 19, 2018):

The Tokyo High Court upheld the acquittals, concurring with the District Court's general approach but offering a more structured test. The High Court opined that Article 66, Paragraph 1 is intended to regulate "advertisement in a broad sense". For an act to qualify as such, it must satisfy three conditions:

- Cognizability: The information must be communicated (or intended to be communicated) to unspecified or numerous persons.

- Specificity: The particular pharmaceutical product in question must be clearly identified within the communication.

- Means of Solicitation: The communication must serve as a means of soliciting customers.

The High Court further elaborated that the "means of solicitation" requirement has two components, both of which must be met:

* (a) Objective Means of Solicitation: The communication, by its content, format, and overall appearance, must objectively possess the characteristics of a tool for attracting customers.

* (b) Subjective Intent of Solicitation: The person making the communication must have the subjective intention of using the communication itself as a means to solicit customers.

In evaluating the two academic papers in question, the High Court found that, given their scientific content, formal structure, and the nature of the academic journals in which they were published, they lacked the objective characteristics of a customer solicitation tool. Furthermore, the High Court viewed the act of publishing in academic journals as being, in the larger scheme of things, a preparatory act for potential future advertising activities. It concluded that Mr. X did not intend the act of academic publication itself to be a direct means of soliciting customers; therefore, the subjective intent for solicitation was also deemed absent. The acquittals were thus affirmed. The public prosecutor appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Definitive Stance (June 28, 2021)

The First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan dismissed the prosecutor's appeal, thereby upholding the acquittals of Mr. X and Y Company. The Supreme Court provided its first authoritative interpretation of the scope of Article 66, Paragraph 1 of the former Pharmaceutical Affairs Law.

The Court's Interpretation of Article 66, Paragraph 1:

- Purpose of the Law and Article 66(1): The Supreme Court began by outlining the overall objective of the Pharmaceutical Affairs Law: to improve public health by ensuring the quality, efficacy, and safety of pharmaceuticals and medical devices through necessary regulations. Within this framework, the specific purpose of Article 66, Paragraph 1 is to prevent public health hazards that could arise from the dissemination of false or exaggerated information regarding the efficacy, effects, etc., of such products. Such misinformation could mislead general consumers or prescribing physicians into selecting and using inappropriate pharmaceuticals, thereby posing a risk to health and safety.

- Scope of Regulated Acts – The "Promotional Means" Test: In light of this protective purpose, the Supreme Court interpreted the phrase "advertise, describe, or disseminate an article" in Article 66(1). It held that these regulated acts refer to communications concerning specific pharmaceutical products that are made as a means of promoting the purchase or prescription of those products to an unspecified or numerous audience. This "means of promoting purchase or prescription" criterion became central to the Court's analysis.

- Objective Assessment Framework: The Court stipulated that when determining whether a particular communication falls under the regulation of Article 66(1), the crucial factor is how that communication is likely to be perceived by its recipients. Whether a communication can be characterized as having been made "as a means of promoting the purchase or prescription" of a specific drug should be judged objectively, based on the communication's content, nature, mode of dissemination, and other relevant circumstances.

Application to the Falsified Academic Papers:

The Supreme Court then applied this interpretive framework to the facts of the case:

- Nature of the Academic Papers: The Court observed that the two papers in question were structured and written according to the standard conventions of academic論文 (papers/theses). They detailed the results of the sub-analysis of the A Study, presented by medical researchers affiliated with a university graduate school. The papers disclosed the research objectives, methodologies, conditions, the researchers' interpretations, and even noted study limitations.

- Nature of the Publication Venues: The journals in which these papers were published were identified as specialized, peer-reviewed academic journals within the medical field.

- Target Audience and Purpose of Academic Publication: Given the sophisticated content of the papers and the specialized nature of the journals, the Supreme Court reasoned that the primary intended readership would consist of researchers, physicians, and other experts in the medical field. The act of submitting and publishing these papers in such journals was, therefore, an announcement of academic research findings by the authoring researchers, directed at their peers within the scientific community.

- Inherent Nature of Academic Discourse: The Court further emphasized that publications in specialized academic journals are, by their very nature, expected to be subjected to rigorous scrutiny, verification, and critique by other experts in the field. Their scientific validity is intended to be established through ongoing scholarly debate, which includes the airing of critical opinions and alternative interpretations. The Supreme Court noted that this fundamental nature of academic publication is not altered by the underlying (and in this case, illicit) actions or motives of the defendant in falsifying the data that formed the basis of the papers.

- Conclusion on the Act of Publication: Based on this analysis, the Supreme Court concluded that the act of publishing these two academic papers in the specified academic journals, even though they were based on falsified data intended by Mr. X for eventual use in promotional materials, did not itself constitute a communication made "as a means of promoting the purchase or prescription" of Drug B. Therefore, this act did not fall within the scope of conduct regulated by Article 66, Paragraph 1 of the former Pharmaceutical Affairs Law.

The acquittals of Mr. X and Y Company were thus finalized. The judgment also noted a supplementary opinion by Justice Atsushi Yamaguchi, who, while fully concurring with the majority, added that interpreting Article 66(1) broadly to cover the creation and publication of academic papers like these could have a significant chilling effect on academic activities, potentially raising concerns regarding the constitutional protection of academic freedom, especially since the article regulates not only "false" but also "exaggerated" statements.

Analysis and Implications: Untangling Academic Freedom and Advertising Regulations

The Supreme Court's decision in this case is a landmark for several reasons, offering significant guidance on the interpretation of pharmaceutical advertising laws in Japan, especially at the sensitive interface with scientific research and publication.

The "Means of Promoting Purchase/Prescription" as a Key Threshold: The Court established a critical filter: for a communication to be caught by Article 66(1), it is not enough that it contains false or exaggerated information about a drug that could be used for promotion later. The act of communication itself (be it advertising, describing, or disseminating) must, when viewed objectively, serve as a means of promoting the drug's purchase or prescription.

Protecting the Realm of Academic Discourse: While the Court did not condone the data falsification (which can be subject to other sanctions, such as academic disciplinary actions, retractions by journals, or loss of credibility), its interpretation effectively protects the act of academic publication in its typical context. The ruling recognizes that the primary purpose and perception of publishing in a peer-reviewed, specialized journal are geared towards scholarly exchange and debate among experts, not direct consumer or prescriber inducement. The fact that the information might be flawed, or even deliberately falsified by a contributor with ulterior motives, does not automatically transform the act of academic publication itself into illegal advertising under this specific statute.

Emphasis on Objective Perception by the Target Audience: The Court's focus on how the communication is received by its intended and likely audience is crucial. Academic papers are primarily for experts who are expected to engage with them critically. This is distinct from promotional materials aimed at a broader audience of consumers or busy prescribers who may not have the same capacity for critical appraisal of scientific claims.

Distinction from Direct Pharmaceutical Promotion: This ruling helps draw a clearer line between communications that are fundamentally academic in nature (even if imperfect or based on manipulated data) and those that are overtly promotional, such as direct-to-consumer advertising (where permitted), brochures for doctors, or presentations at promotional symposia clearly designed to boost sales.

The "Preparatory Act" Nuance: The High Court had characterized the academic publications as "preparatory acts" for future advertising. The Supreme Court, however, focused more on the intrinsic nature and objective perception of the act of publication in an academic journal itself, finding it did not meet the "promotional means" test. This suggests that while underlying intent for future misuse is relevant, the character of the immediate act of communication is paramount for Article 66(1) liability.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's June 28, 2021, decision provides significant legal clarity in Japan regarding the application of pharmaceutical advertising laws to scientific publications. By establishing that the act of communication must itself be a "means of promoting purchase or prescription," the Court has set a standard that respects the distinct nature of academic discourse while still aiming to protect public health from directly misleading promotional activities. This judgment will undoubtedly influence how pharmaceutical companies, researchers, and regulatory authorities navigate the boundaries between legitimate scientific exchange and the illegal promotion of medical products. It underscores that while the integrity of underlying research data is vital, the legal characterization of its dissemination depends heavily on the context, purpose, and perception of the communication itself.