Abuse of System: Japan's Supreme Court Denies Foreign Tax Credits in a Landmark Tax Avoidance Case

Judgment Date: December 19, 2005

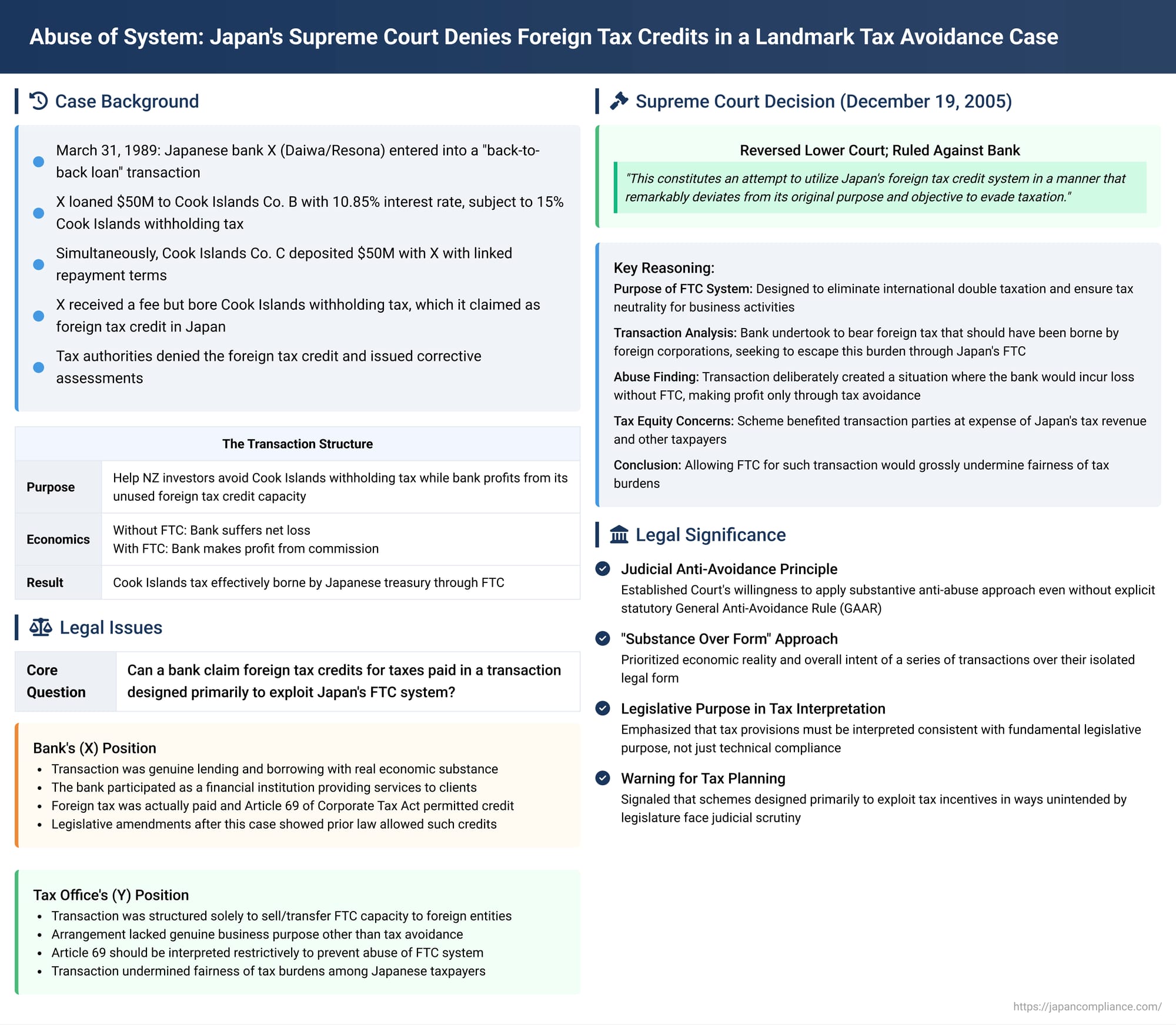

In a highly influential decision concerning international tax avoidance, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan denied a major Japanese bank the benefit of foreign tax credits arising from a complex "back-to-back loan" transaction. The Court, looking beyond the formal structure of the deal, concluded that the transaction was designed to abuse Japan's foreign tax credit system and grossly undermine tax fairness. This case, often referred to as the "Resona Foreign Tax Credit Case" (though the bank's specific name at the time of the transaction was Daiwa Bank), established an important precedent for how Japanese courts might address sophisticated tax avoidance schemes, even in the absence of a broadly applicable statutory general anti-avoidance rule (GAAR) for such specific interpretations.

The Japanese Foreign Tax Credit System

At its core, the Japanese foreign tax credit (FTC) system, governed by Article 69 of the Corporate Tax Act (as it stood before the 1998 amendments relevant to this case), is designed to mitigate international double taxation. When a Japanese domestic corporation earns foreign source income and pays foreign corporate taxes on that income, the FTC system allows the corporation to credit those foreign taxes against its Japanese corporate tax liability, subject to certain limitations. The primary policy objectives are to prevent the same income from being fully taxed twice (once abroad and once in Japan) and to ensure a degree of tax neutrality for Japanese companies engaging in international business activities.

A key feature of Japan's FTC system is the "overall limitation method." This means that the maximum amount of foreign tax that can be credited is calculated based on the corporation's total worldwide income and its total foreign source income. The formula is essentially: (Japanese Corporate Tax before FTC) x (Total Foreign Source Income / Total Worldwide Income). If a company has paid foreign taxes at effective rates lower than Japan's corporate tax rate on some of its foreign income, it may have "excess FTC capacity" or "excess limitation." This unused capacity can then absorb foreign taxes paid at higher rates on other foreign income, or, as this case illustrates, foreign taxes incurred in specific types of transactions.

The Intricate "Back-to-Back Loan" Transaction

The case revolved around a sophisticated financial transaction proposed to X (a major Japanese bank, then Daiwa Bank, via DKB, another major Japanese bank at the time) by F Co., a prominent New Zealand financial institution. The transaction was structured as follows:

- The Underlying Goal: NZ Co. A, a New Zealand corporation managing investor funds, aimed to invest these funds (originally sourced from investors) into New Zealand dollar-denominated Eurobonds in the Cook Islands. To reduce its New Zealand corporate tax burden on the investment profits, NZ Co. A decided to channel the investments through a wholly-owned subsidiary, Cook Islands Co. B, established in the Cook Islands, a jurisdiction with a lower corporate tax rate (a tax haven).

- Avoiding Cook Islands Withholding Tax (Initial Layer): To further mitigate taxation, specifically potential Cook Islands withholding tax on investments made directly by investors, the funds were first to be acquired by Cook Islands Co. C. Co. C was another Cook Islands corporation in which NZ Co. A held a 28% stake. The idea was for Co. C to make the funds available to Co. B for the actual investment operations.

- The Problem with Direct Lending (C to B): If Cook Islands Co. C were to lend the funds directly to Cook Islands Co. B, interest payments from Co. B to Co. C would be subject to a 15% withholding tax in the Cook Islands.

- X's Interposition (The Back-to-Back Loan): To circumvent this 15% Cook Islands withholding tax on Co. C, X (Daiwa Bank, through its Singapore branch) was inserted into the structure as an intermediary. This was executed on March 31, 1989, through two main contracts:

- The Loan Agreement (X to Co. B): X agreed to lend USD 50 million to Cook Islands Co. B at an annual interest rate of 10.85%. Under the terms, Co. B would pay interest to X after deducting the 15% Cook Islands withholding tax.

- The Deposit Agreement (Co. C with X): Simultaneously, X agreed to accept a deposit of USD 50 million (the same amount as the loan) from Cook Islands Co. C. The terms were intricately linked:

- Repayment of the deposit principal by X to Co. C was contingent upon X receiving repayment of the loan principal from Co. B.

- When X received the (net-of-withholding-tax) interest from Co. B, X would then pay deposit interest to Co. C. This deposit interest was calculated as: the gross interest X was due from Co. B (i.e., pre-withholding tax amount) plus the amount of the Cook Islands withholding tax suffered by X, minus a commission or margin for X (calculated based on a specific interest rate spread).

- The Economic Effects:

- For Cook Islands Co. C: This structure allowed it to effectively receive the full interest income from the funds (which were ultimately used by Co. B) without directly suffering the 15% Cook Islands withholding tax, as the tax was formally borne by X.

- For X (Daiwa Bank):

- Pre-tax (and pre-Japanese FTC): X would earn a net profit equal to its commission/margin.

- After Cook Islands Withholding Tax (but pre-Japanese FTC): Since the 15% withholding tax paid by X on the interest received from Co. B was designed to be larger than X's commission, this specific transaction, viewed in isolation before considering Japanese FTC, would result in a net loss for X.

- After Japanese Foreign Tax Credit: However, X intended to claim the Cook Islands withholding tax it paid as a foreign tax credit against its Japanese corporate tax liability. Because X had other foreign source income and sufficient "excess FTC capacity" due to Japan's overall limitation method, it planned to credit the entire amount of the Cook Islands withholding tax. This would turn the otherwise loss-making transaction (after Cook Islands tax) into a profitable one for X.

In essence, X was using its existing FTC capacity, generated from unrelated international operations, to absorb the Cook Islands withholding tax, allow Co. C to avoid that tax, and still make a profit on the commission. The Japanese treasury would effectively bear the cost of the Cook Islands tax by allowing X to reduce its Japanese tax liability.

Tax Office Challenge and Lower Court Rulings

The tax office chief, Y (defendant/appellant), challenged this arrangement and denied the foreign tax credit claimed by X for the Cook Islands withholding tax. Y issued corrective corporate tax assessments and underpayment penalties. X contested this through administrative appeals and then filed a lawsuit.

- Osaka District Court (First Instance):

- Y argued primarily that the loan and deposit contracts between X, Co. B, and Co. C were effectively sham transactions or collusive fictitious displays, void under private law. Y contended that the parties' true intent was not genuine lending and borrowing but rather to avoid Cook Islands withholding tax and for X to "sell" its FTC capacity.

- As a subsidiary argument, Y proposed a "restrictive interpretation" (gentei kaishaku) of Article 69 of the Corporate Tax Act, asserting that foreign taxes paid in transactions lacking a legitimate business purpose should not qualify for the FTC.

- The District Court rejected Y's primary argument (that the contracts were shams). It also found that it could not deny a business purpose for X and thus rejected the restrictive interpretation argument. The court ruled in favor of X, cancelling the tax office's dispositions.

- Osaka High Court (Appellate Court):

- Y bolstered its argument for a restrictive interpretation, emphasizing that X had intentionally structured a transaction that created double taxation purely to exploit the FTC system, which amounted to an abuse.

- The High Court, however, also found in favor of X. It reasoned that X, as a financial institution, undertook the transaction as part of its banking business. X's goal was to provide a lower-cost financing solution to its clients (Co. C and Co. B) by utilizing its existing FTC capacity, and to earn a fee for this service. The High Court viewed this as a legitimate business purpose for X. While acknowledging that X's actions did result in double taxation (first in the Cook Islands, then intended to be relieved in Japan), it did not consider this an abuse of the FTC system.

- The High Court also pointed to the fact that the Japanese Diet had subsequently amended the Corporate Tax Act (in 2001 and 2002) to specifically render transactions similar to the one in question ineligible for FTC. Since these amendments were applied prospectively (to transactions from April 1, 2001, onwards), the High Court inferred that the pre-amendment law (which applied to X's 1989 transaction) must have permitted such FTC claims. The tax office's appeal was dismissed.

Y, the tax office chief, then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's "Substance Over Form" Reversal

The Supreme Court overturned the decisions of both lower courts and ruled decisively in favor of the tax authorities, denying X the foreign tax credit. The Court's reasoning focused on the purpose of the FTC system and the abusive nature of the transaction.

I. The Purpose of the Foreign Tax Credit System

The Court began by reiterating the established policy objectives of the FTC system under Article 69 of the Corporate Tax Act:

"The foreign tax credit system stipulated in Article 69 of the Corporate Tax Act is a system whereby, when a domestic corporation becomes liable to pay foreign corporate tax, it may, within certain limits, deduct the amount of said foreign corporate tax from the amount of its Japanese corporate tax. This is a system based on the policy objectives of eliminating international double taxation on the same income and ensuring tax neutrality for business activities."

II. Finding an Abuse of the Foreign Tax Credit System

The Supreme Court then critically analyzed the "back-to-back loan" transaction, looking at its overall substance and effect:

- Overall Assessment: "However, the transaction in this case, when viewed as a whole, can be described as one in which X, a Japanese bank, undertook, in return for a fee, to bear a foreign corporate tax that should originally have been borne by foreign corporations. X then sought to escape this burden by utilizing its excess foreign tax credit capacity to reduce the corporate tax payable in Japan, ultimately aiming to make a profit."

- Mechanism and Intent of Abuse: "This constitutes an attempt to utilize Japan's foreign tax credit system in a manner that remarkably deviates from its original purpose and objective to evade taxation. It involves reducing the corporate tax payable in Japan and then having the transaction parties enjoy profits derived from this avoided tax as their source. This was achieved by deliberately undertaking the transaction in question, which, by itself (i.e., if the foreign corporate tax were borne without the benefit of the Japanese FTC), would only result in a loss."

- Harm to Japanese Revenue and Taxpayer Equity: "This can only be described as a scheme to benefit the transaction parties at the expense of Japan and, by extension, Japan's taxpayers."

- Conclusion on Impermissibility: "Given this, to treat the foreign corporate tax arising from the income generated by the transaction in this case as eligible for the foreign tax credit stipulated in Article 69 of the Corporate Tax Act would be an abuse of the foreign tax credit system, and furthermore, it must be said that it is impermissible as it would grossly undermine the fairness of tax burdens."

Judgment and Its Enduring Significance

The Supreme Court quashed the High Court's judgment and the first instance judgment (both of which had favored X), and dismissed X's original claims entirely. The denial of the foreign tax credit by the tax authorities was thereby upheld.

This 2005 ruling is a landmark in Japanese tax law, particularly in the area of tax avoidance, for several critical reasons:

- Judicial Anti-Avoidance Principle: It demonstrated the Supreme Court's willingness to apply a substantive anti-abuse approach to a specific tax provision (the FTC), even in the absence of a comprehensive statutory General Anti-Avoidance Rule (GAAR) that would explicitly authorize such recharacterization for this type of specific interpretation. The Court looked beyond the transaction's technical compliance with the letter of the law to its underlying economic reality and its consistency with the provision's purpose.

- "Substance Over Form" Prevails: The Court effectively prioritized the economic substance and overall intent of the series of transactions over their isolated legal forms. While individual loan and deposit agreements might have appeared formally valid, their combined effect and purpose were deemed abusive.

- Focus on Legislative Purpose and Tax Equity: The decision strongly emphasized that tax provisions must be interpreted and applied in a manner consistent with their fundamental legislative purpose. Schemes that "remarkably deviate" from such purposes and lead to results that "grossly undermine the fairness of tax burdens" will not be countenanced.

- Implications for Sophisticated Tax Planning: The case sent a clear signal that highly artificial or circular schemes designed solely or primarily to exploit specific tax incentives (like the FTC) in ways unintended by the legislature are vulnerable to challenge, even if they are meticulously structured to meet the literal wording of the law.

- "Restrictive Interpretation" Broadly Conceived: While sometimes categorized as a case of "restrictive interpretation" (gentei kaishaku) of a tax provision, the Court did not narrowly redefine a specific term within Article 69. Instead, it effectively denied the application of the entire FTC benefit to the transaction due to its abusive nature, finding that the transaction as a whole fell outside the intended scope and spirit of the FTC system.

The "Resona Foreign Tax Credit Case" remains a pivotal authority in Japan for understanding the limits of tax planning and the judiciary's role in preventing the abuse of tax laws. It highlights that adherence to the spirit and purpose of tax legislation, alongside considerations of overall tax fairness, can, in exceptional circumstances, override a purely literal application of statutory text.