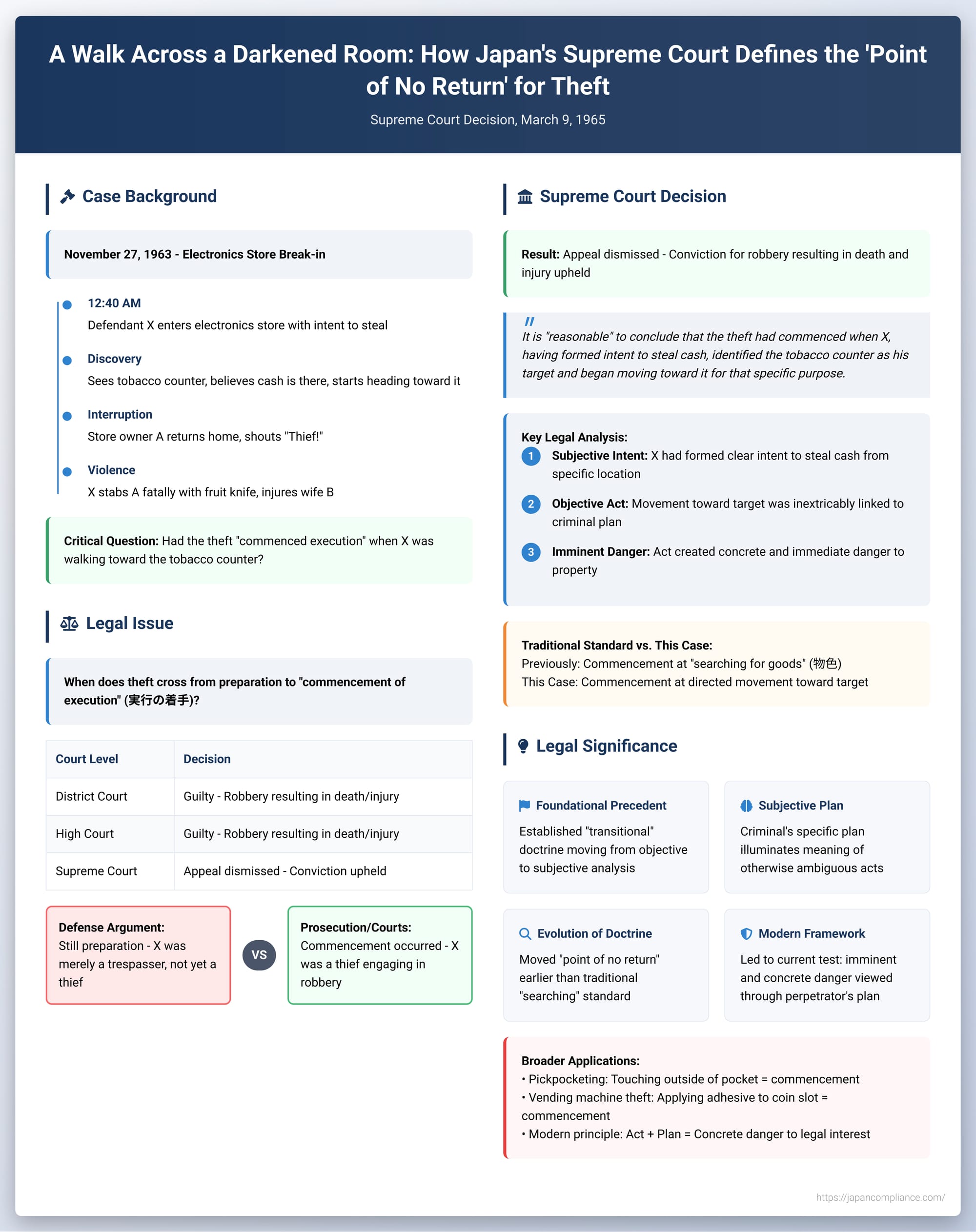

A Walk Across a Darkened Room: How Japan's Supreme Court Defines the 'Point of No Return' for Theft

In criminal law, the line between merely preparing for a crime and actually beginning to commit it is one of the most critical and debated topics. This boundary, known in Japanese law as the "commencement of execution" (実行の着手 - jikkō no chakushu), determines when a person's actions transform from non-criminal preparation into a punishable criminal attempt. A landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on March 9, 1965, provides a masterclass in this distinction. The case revolved around a seemingly simple question: does the act of walking across a room with the intent to steal constitute the beginning of a theft? The answer would determine whether a man was guilty of homicide or the far more serious crime of robbery-homicide.

The Facts of the Case

On November 27, 1963, at approximately 12:40 AM, a man identified as X entered an electronics store with the intent to commit theft. The store was dark, and he used a small flashlight to look around. He first saw stacks of electrical appliances but decided he would rather steal cash. He then spotted a tobacco counter on his left side, a place where he believed cash would be kept. With the firm intention of stealing money from that location, he "started to head towards" the tobacco counter.

At that exact moment, the store's owner, A, returned home with his wife, B. Discovering X inside the premises, A shouted, "Thief!" Panicked and desperate to escape arrest, X pulled out a fruit knife he was carrying and stabbed A in the chest, inflicting a fatal wound. He then proceeded to strike B with his fists, causing her injury.

The Crucial Question: When Did the Theft Begin?

The legal classification of X's horrific actions hinged entirely on the concept of "commencement of execution." The legal stakes were immense:

- Scenario 1: The Theft Had Not Commenced. If X's act of "starting to head towards" the counter was still considered mere preparation, then he was legally a trespasser at the moment he was discovered. His subsequent violence would be treated as separate crimes: homicide (or a variant like assault resulting in death) and assault/injury.

- Scenario 2: The Theft Had Commenced. If, however, his actions constituted the commencement of the theft, he was legally a "thief" at the moment of discovery. Under Article 238 of the Japanese Penal Code, a thief who uses violence or threats to escape arrest or conceal the stolen goods is guilty of robbery. Consequently, the killing of A and injuring of B would constitute the single, gravely serious offense of robbery resulting in death and injury (強盗致死傷罪 - gōtō chishishōzai).

The defense argued for the first scenario, asserting that X had not yet begun the act of theft and therefore could not be a "robber." The lower courts, however, sided with the prosecution. Both the District Court and the High Court ruled that X's act of moving toward the tobacco counter was an act "extremely closely connected" to the intended theft and thus marked its commencement. The case then went to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Intent Illuminates the Act

The Supreme Court of Japan upheld the lower courts' decisions and affirmed the conviction for robbery resulting in death and injury. In its reasoning, the Court found it "reasonable" to conclude that the theft had commenced. The decision pivoted on the specific facts: X, having already formed the intent to steal cash, identified a specific target (the tobacco counter) and began to move toward it for that purpose.

This ruling is significant because it recognized the commencement of theft at a stage earlier than the traditional standard. For decades, Japanese courts had typically found the commencement of theft in cases of burglary at the point of "searching for goods" (物色 - bussoku). An intruder simply being present in a building was not enough; the attempt was deemed to begin when they started actively looking through drawers, opening closets, or otherwise rummaging for valuables.

The 1965 decision moved the "point of no return" back. It established that an action preceding the physical search for goods could, in fact, constitute the commencement of the crime, provided it was inextricably linked to the perpetrator's immediate criminal plan.

A "Transitional" Case: Evolving the Doctrine of Commencement

Legal scholars view this case as a pivotal "transitional" ruling in the evolution of Japanese jurisprudence on criminal attempts. It marked a shift from a purely objective view of a perpetrator's actions toward a more nuanced standard that considers the perpetrator's subjective state of mind to interpret the meaning of those actions.

This evolution led to the modern, established principle in Japanese case law, which was fully crystallized in a later, famous ruling (the "Chloroform Murder Case" of 2004). This principle holds that the commencement of execution is determined by assessing whether an act creates an imminent and concrete danger of harm to the legally protected interest (in this case, property), when that act is viewed in light of the perpetrator's specific plan of action (所為計画 - shoi keikaku).

The 1965 case was a critical step toward this modern standard. The court looked at an objectively ambiguous act—walking across a room—and gave it its criminal character by considering the defendant's subjective plan.

To break it down:

- The Act: Walking towards a tobacco counter.

- The Plan: "I want to steal cash, which I believe is at that counter, and I am heading there now to take it."

When fused together, the act is no longer innocent or merely preparatory. It becomes the first, indispensable step in the immediate execution of the crime. The danger to the store owner's property was no longer abstract or potential; in the context of X's plan, the danger became concrete and imminent the moment he set his course for the counter. If he had not been interrupted, the next immediate action would have been the rummaging for and taking of the money. There were no further preparatory steps needed.

Broader Applications and Related Rulings

This principle of interpreting an act through the lens of the criminal's plan helps clarify the commencement of execution in various types of theft:

- Pickpocketing (Suri): Japanese courts have held that the preparatory act of "atari" (bumping into a target to check for the location and existence of a wallet) is generally not the commencement of theft. However, the act of touching the outside of the target's pocket with the intent to steal is considered commencement. At that point, the perpetrator's plan has advanced to the final stage before the physical taking, and the act is no longer ambiguous.

- Theft from Vending Machines: In a more recent case, a man attempted to steal money from a vending machine by applying a strong adhesive to the coin return slot, intending for customers' change to get stuck for him to collect later. A lower court ruled that the act of applying the glue was the commencement of the theft. It was not the taking itself, but it was the most critical and indispensable act in the defendant's unique criminal plan. It created the objective condition for the theft to succeed and was directly and immediately linked to the acquisition of the coins.

Conclusion

The 1965 decision is a cornerstone of Japanese criminal law because it provides a sophisticated answer to a fundamental question. It teaches that the "point of no return" is not determined by a rigid, objective checklist of actions. Instead, it is the moment when a person's conduct, illuminated by their specific criminal plan, creates a real and immediate danger that the intended crime will be completed. A simple walk across a darkened room, when undertaken as the first step in a plan to steal, ceases to be mere preparation and becomes the beginning of a crime. In this case, that legal distinction was the difference that turned a fatal assault into a conviction for one of Japan's most serious offenses.