A Tangled Web: When a Parent's Guarantee for a Third Party Puts Children's Assets at Risk

Judgment Date: October 8, 1968 (Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench)

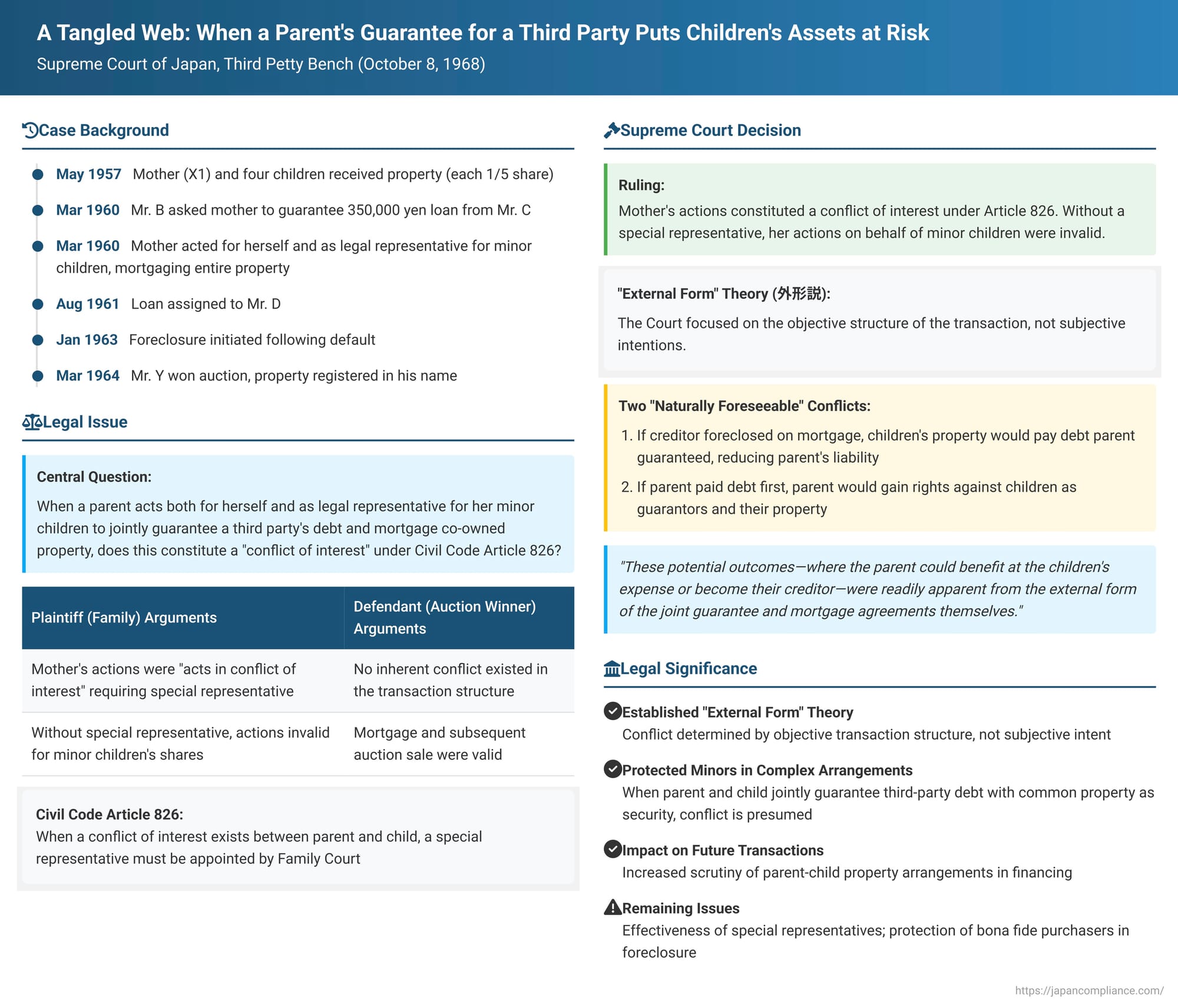

In a significant 1968 ruling, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed a complex scenario where a mother, acting for herself and as the legal representative for her minor children, jointly guaranteed a third party's debt and mortgaged property co-owned with her children as security. The Court found that such an arrangement constituted a "conflict of interest" under the Japanese Civil Code, rendering the mother's actions on behalf of her minor children legally ineffective without the appointment of a special representative. This case delves into the crucial legal safeguards designed to protect minors when their parent's interests may diverge from their own.

A Complex Web of Guarantees and Family Assets: The Facts

The case involved Ms. X1, who had divorced her ex-husband, Mr. A. As part of their arrangements, on May 5, 1957, Ms. X1 and four of their six children (X2, X3, X4, who were minors at the relevant time, and X5, an adult son) were gifted land and a building previously owned by Mr. A. Each received a 1/5 co-ownership share in this property.

Later, Ms. X1 became acquainted with Mr. B, who was planning to establish a medical clinic. On March 10, 1960, Mr. B sought to borrow 350,000 yen from a lender, Mr. C, to fund his clinic. Mr. B earnestly requested Ms. X1 to act as a joint and several guarantor for this loan and to consent to a mortgage being placed over the entire co-owned property (hers and the children's shares) as security. Ms. X1 agreed.

In this transaction, Ms. X1 acted in multiple capacities:

- For herself, as one of the co-owners of the property.

- As the person with parental authority (legal representative) for her minor children, X2, X3, and X4.

- She also purported to act as the representative for her adult son, X5, though the appellate court later found she lacked the authority to do so for him.

Thus, Ms. X1 entered into joint and several guarantee contracts for Mr. B's debt and, to secure this same debt, created a mortgage over the entire property (including all five co-owned shares) in favor of Mr. C. This mortgage was registered on March 12, 1960. This type of security, where a third party's property is pledged for another's debt, is known as butsujō hoshō (物上保証).

Subsequently, on August 14, 1961, the lender, Mr. C, assigned the mortgage-backed loan to Mr. D. When Mr. B presumably defaulted, Mr. D initiated foreclosure proceedings on the mortgaged property on January 25, 1963. On July 22, 1963, the court approved Mr. Y as the successful bidder in the foreclosure auction. Ownership of the property was formally registered in Mr. Y's name on March 30, 1964.

Ms. X1 and her children (X2-X5) then filed a lawsuit against Mr. Y, seeking to cancel the ownership transfer registration. Their primary arguments were:

- The joint guarantee and the mortgage creation were "acts in conflict of interest" (利益相反行為, rieki sōhan kōi) under Article 826 of the Civil Code with respect to the minor children (X2, X3, and X4). Because Ms. X1 acted without a court-appointed special representative for the children in this conflict situation, her actions on their behalf were invalid.

- Regarding the adult son, X5, they argued he had not consented to the mortgage on his share, and Ms. X1 had acted without his authority.

The Lower Courts' Rulings

- The first instance court dismissed the claims of Ms. X1 and her children.

- The appellate court, however, partially sided with them. It found that Ms. X1's actions on behalf of her minor children (X2-X4) indeed constituted a conflict of interest, making the mortgage on their shares invalid. It also found that Ms. X1 lacked the authority to encumber X5's share. Consequently, the appellate court ruled that Mr. Y had only validly acquired Ms. X1's 1/5 share of the property, and the mortgage and subsequent sale were invalid concerning the shares of X2, X3, X4, and X5.

Mr. Y appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: A Conflict of Interest Affirmed

The Supreme Court dismissed Mr. Y's appeal, thereby upholding the appellate court's finding that Ms. X1's actions on behalf of her minor children constituted a conflict of interest.

The Court's reasoning focused on the "external form" (外形, gaikei) of the transactions and the "naturally foreseeable" consequences:

- The Court highlighted the specific facts: Ms. X1, at Mr. B's request, acted both for herself as a co-owner and as the legal representative of her minor children (X2, X3, X4), and also purported to act for her adult son (X5), to jointly and severally guarantee Mr. B's debt to Mr. C. Simultaneously, she pledged the entire co-owned property as security for this same debt.

- The Court reasoned that from the very structure of these acts, certain conflicts were "naturally foreseeable":

- Scenario 1: Foreclosure by the Creditor: If the creditor chose to foreclose the mortgage (as happened here), the proceeds from the sale of the children's shares in the property would be applied to repay Mr. B's debt. To the extent this happened, Ms. X1's own potential liability as a joint and several guarantor would be reduced. In this scenario, Ms. X1 would directly benefit from the children's property being used to satisfy a debt she also guaranteed, placing her interests in conflict with her children's interest in preserving their property.

- Scenario 2: Creditor Pursues Parent's Guarantee: Alternatively, if the creditor chose to pursue Ms. X1 directly for her guarantee liability and she paid off Mr. B's debt, complex legal issues would arise between her and her children. Ms. X1 would gain a right of recourse (求償関係, kyūshō kankei) not only against the principal debtor (Mr. B) but also potentially against her children as fellow joint guarantors for their respective shares of the debt. Furthermore, by paying the debt, Ms. X1 could be subrogated (代位, dai'i) to the creditor's rights, including the mortgage over the children's shares of the property. This would effectively make her a creditor to her own children, with a security interest in their property.

- The Supreme Court concluded that these potential outcomes—where the parent could benefit at the children's expense or become their creditor—were readily apparent from the "external form" of the joint guarantee and mortgage agreements themselves.

- Therefore, the appellate court's determination that Ms. X1's actions on behalf of her minor children (X2, X3, and X4) constituted "acts in conflict of interest" under Civil Code Article 826 was correct.

Understanding "Conflict of Interest" in Japanese Family Law (Civil Code Article 826)

Article 826 of the Japanese Civil Code is a crucial provision designed to protect minors. While a person with parental authority generally has comprehensive rights to represent their minor child in legal acts (Civil Code Art. 824) and consent to acts the child undertakes, Article 826 places a key limitation:

- If an act involves a conflict of interest between the person with parental authority and the child, or

- If an act involves a conflict of interest between multiple children under the same person's parental authority,

then the person with parental authority must petition the Family Court for the appointment of a special representative (特別代理人, tokubetsu dairinin) to act on behalf of the child(ren) for that specific transaction. Failure to do so renders the parent's actions on behalf of the child invalid.

Historically, Article 826 was sometimes viewed as a mechanism to enable transactions that might otherwise be barred by general prohibitions against self-contracting or dual representation (similar to the current Civil Code Article 108(1)). However, through judicial interpretation, its primary purpose has evolved to be understood as the protection of the child's interests when those interests might diverge from the parent's. Case law and prevailing academic theory have expanded its application beyond direct transactions between parent and child to include acts undertaken by the parent (representing the child) with a third party, if an inherent conflict of interest exists.

The "External Form" Theory for Judging Conflicts

Japanese courts, including the Supreme Court in this 1968 decision, have predominantly adopted what is known as the "external form" theory (gaikei-setsu 外形説) or "formal judgment" theory (keishiki-teki handan-setsu 形式的判断説) for determining whether a conflict of interest exists.

- This approach involves an objective assessment based on the nature and structure of the legal act itself, rather than delving into the parent's subjective motives or the actual outcome of the transaction.

- The focus is on whether the external appearance of the act inherently creates a situation where the parent's interests and the child's interests could diverge or oppose each other.

- This contrasts with the "substantive judgment" theory (jisshitsu-teki handan-setsu 実質的判断説), which, though influential, argues for considering all concrete circumstances—such as the parent's motivations, the purpose of the act, its ultimate benefit or detriment to the child, and its necessity—to determine if a real, substantive conflict exists. For example, if a parent mortgages a child's property to pay for the child's essential upbringing expenses, the formal theory might still see a conflict (as the parent is relieved of a financial burden), while the substantive theory might find no conflict if the act was ultimately for the child's benefit.

The Supreme Court, in this and other cases, has generally favored the "external form" theory, emphasizing the need for legal certainty and the protection of transactional security, as third parties dealing with the parent might not be aware of the internal family dynamics or motivations.

Application of the "External Form" Theory to Guarantees and Mortgages

This 1968 Supreme Court ruling was a significant clarification for complex situations where a parent and child jointly secure a third party's debt. The Court looked at the structure of the mother (X1) and her minor children (X2-X4) all becoming joint and several guarantors for Mr. B's debt, coupled with their entire co-owned property being mortgaged for that same debt. The "external form" of this arrangement made it "naturally foreseeable" that Ms. X1's interests could diverge from her children's:

- If the property was sold in foreclosure, the children's shares would go towards paying a debt that Ms. X1 was also liable for. Her personal financial exposure would decrease at the cost of her children's assets.

- If Ms. X1 paid the debt herself to avoid foreclosure, she would then have the right to seek contribution from her children as co-guarantors and could potentially step into the lender's shoes regarding the mortgage on the children's property. This would turn her into a creditor against her own children.

Because these scenarios of potential benefit to the parent at the child's expense were inherent in the structure of the transaction, it was deemed a conflict of interest, regardless of Ms. X1's actual intentions at the time. Subsequent Supreme Court cases have reinforced this line of reasoning, establishing that when a parent and child are jointly involved as guarantors or providers of security for a third party's debt, this is generally considered a conflict of interest based on the objective nature of the transaction.

Remaining Issues and Modern Context

While this 1968 decision provided crucial clarity, some related issues continue to be discussed:

- Effectiveness of Special Representatives: The system of appointing a special representative is intended to protect the child's interests, but critics have long pointed out that such representatives can sometimes act as mere "shadows" of the parent, not always providing robust, independent advocacy for the child. Ongoing efforts to ensure truly effective protection for minors in such situations are necessary.

- Impact of Later Legal Reforms: The Japanese Civil Code has undergone revisions since 1968. For example, amendments related to guarantees (effective 2020) introduced stricter requirements for ensuring a guarantor understands their obligations, including a "declaration of guarantee intention" (民法465条の6・465条の9). How these newer rules might interact with situations involving minors represented by parents in conflict-of-interest scenarios is a developing area.

- Protection of Bona Fide Purchasers in Foreclosure: A critical practical point, under current Japanese civil execution law (Civil Execution Act Art. 184), is that if a property is sold at a foreclosure auction, a bona fide purchaser typically acquires good title, even if the underlying mortgage is later found to have been invalid due to a reason like lack of authority or a conflict of interest in its creation. This means that while the mortgage might have been invalidly placed on the children's shares concerning Ms. X1 and the lender, Mr. Y (as the auction purchaser) might still be protected, complicating the recovery for the children.

Conclusion: Upholding Child Protection through Objective Standards

The 1968 Supreme Court decision stands as a key precedent in Japanese family law, firmly establishing that when a parent acts for themselves and their minor children to jointly guarantee a third party's debt and simultaneously mortgage commonly owned property as security, such actions constitute a conflict of interest requiring the appointment of a special representative for the minors. The ruling's adherence to the "external form" theory emphasizes that the potential for diverging interests, foreseeable from the objective structure of the transaction, is sufficient to trigger these protective measures, regardless of the parent's subjective intentions. This case underscores the law's commitment to safeguarding the financial interests of children, even within complex family and third-party financial arrangements, by applying objective standards to identify and mitigate potential conflicts.