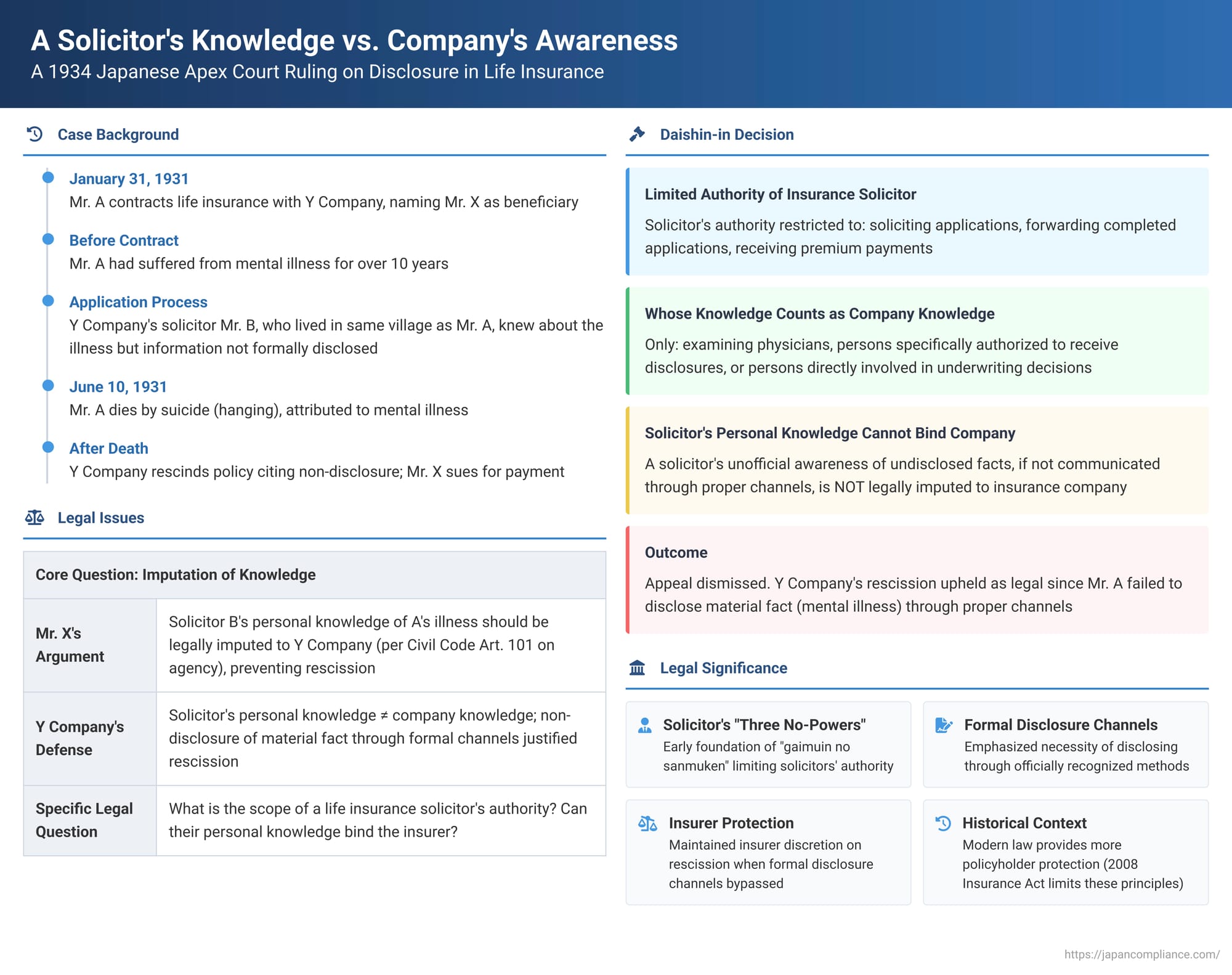

A Solicitor's Knowledge vs. Company's Awareness: A 1934 Japanese Apex Court Ruling on Disclosure in Life Insurance

Judgment Date: October 30, 1934

Court: Daishin-in (Great Court of Cassation), Second Civil Department

Case Name: Insurance Claim Case

Case Number: Showa 9 (O) No. 1548 of 1934

Introduction: The Vital Importance of Disclosure in Life Insurance Contracts

Life insurance contracts are built on a foundation of trust and transparency, particularly concerning the information provided by the applicant about the life to be insured. The "duty of disclosure" (告知義務 - kokuchi gimu) requires applicants and insured individuals to provide the insurance company with full and accurate information about all facts material to the risk the insurer is being asked to undertake. This typically includes detailed information about the applicant's health and medical history. Based on these disclosures, the insurer assesses the level of risk and makes critical decisions: whether to issue a policy at all, what the appropriate premium should be, and whether any special conditions or exclusions might apply.

A failure by the applicant or the insured to disclose material facts, or the provision of untrue statements about such facts, can have serious consequences. Under Japanese insurance law, both historically and currently, such a breach of the duty of disclosure can give the insurer the right to rescind (cancel from the beginning) the insurance contract and, consequently, to deny any claims made under it.

However, the practical process of applying for life insurance often involves interactions with various representatives of the insurance company. These can include insurance solicitors or canvassers (外交員 - gaikōin or 勧誘員 - kan'yūin in the terminology of the era of this case), whose primary role is to find potential customers and assist them with applications, and also examining physicians (診査医 - shinsai) who conduct medical assessments on behalf of the insurer. This raises vital legal questions about the scope of authority of these individuals. Specifically, if an applicant orally discloses a pre-existing medical condition to the insurer's soliciting agent, but this information is not formally conveyed to the insurer's underwriting department (for example, it's not written on the application form), is the insurance company legally deemed to "know" about that condition? Can the insurer later deny a claim based on non-disclosure if its own solicitor was personally aware of the condition but it wasn't formally reported through other channels? This complex issue of imputed knowledge and the limits of a solicitor's agency authority was addressed in a very early but influential 1934 decision by the Daishin-in, Japan's highest court at that time.

The Facts: A Long-Standing Illness, an Insurance Policy Application, and a Tragic Outcome

The case concerned Mr. A, who, on January 31, 1931, entered into a whole life insurance contract with Y Life Insurance Company. The policy insured Mr. A's life for a sum of 2,000 yen, and Mr. X was named as the beneficiary.

Tragically, a few months later, on June 10, 1931, Mr. A died by suicide (specifically, by hanging). His death was attributed to a mental illness from which he had reportedly suffered for over ten years prior to the conclusion of the insurance contract.

Y Life Insurance Company, upon learning of Mr. A's long-standing, undisclosed pre-existing mental illness, took action to rescind the insurance contract. The company asserted that Mr. A had breached his duty of disclosure by failing to reveal this material medical history at the time the policy was applied for. Consequently, Y Company refused to pay the death benefit to the beneficiary, Mr. X.

Mr. X then filed a lawsuit against Y Life Insurance Company, seeking payment of the insurance proceeds. The first instance court and the subsequent appellate court both upheld Y Company's rescission of the contract, ruling against Mr. X.

Mr. X appealed this outcome to the Daishin-in. His central argument was that Mr. B, who was Y Company's employee and the solicitor who had canvassed Mr. A for the insurance policy, had lived in the same village as Mr. A for many years and, as a result, personally knew about Mr. A's pre-existing mental illness at the time the insurance contract was being arranged. Mr. X contended that Y Company had effectively concluded the contract through Mr. B acting as its agent. Therefore, Mr. X argued, under the principles of agency law (specifically, Article 101 of the Japanese Civil Code, which deals with how an agent's knowledge can affect the principal), Mr. B's personal knowledge of Mr. A's illness should be legally imputed to Y Life Insurance Company. If Y Company was deemed to know (or should have known through its agent) the true facts, then it could not subsequently rescind the policy for non-disclosure. The lower courts' failure to impute Mr. B's knowledge to Y Company was, in Mr. X's view, a legal error.

The Core Legal Issue: Can a Solicitor's Personal Knowledge of an Applicant's Pre-Existing Health Condition be Legally Imputed to the Insurance Company?

The crux of the appeal before the Daishin-in was the legal scope of an insurance solicitor's agency authority within the context of the duty of disclosure:

- What is the typical extent of a life insurance solicitor's authority when interacting with potential policyholders?

- Does such a solicitor generally have the legal power to receive, on behalf of the insurance company they represent, legally binding disclosures of material facts related to an applicant's health or medical history?

- If a solicitor personally knows a material fact about an applicant's health (such as a long-standing illness), but that fact is not formally disclosed to the insurer's central underwriting department (e.g., it is not written on the official application form, and perhaps not revealed during a formal medical examination if one occurred), is the insurance company legally considered to "know" that fact simply because its soliciting agent was aware of it? If so, would this imputed knowledge prevent the insurer from later rescinding the policy due to the applicant's failure to disclose that same fact through formal channels?

The Lower Courts' Rulings

Both the court of first instance and the appellate court had found in favor of Y Life Insurance Company. They had upheld the insurer's rescission of the contract, which implies they did not accept Mr. X's argument that the solicitor Mr. B's personal knowledge of Mr. A's mental illness should be imputed to Y Company.

The Daishin-in's Decision (October 30, 1934): Solicitor's Knowledge is Not Automatically the Insurer's Knowledge

The Daishin-in, Japan's highest court, dismissed Mr. X's appeal. It affirmed the lower courts' decisions and upheld Y Life Insurance Company's right to rescind the policy due to the non-disclosure of Mr. A's pre-existing mental illness. The Court's reasoning focused on defining the limited authority of an insurance solicitor:

The Limited Authority of an Insurance Solicitor (外交員 - Gaikōin)

The Daishin-in first addressed the status and role of Mr. B, the individual whom Mr. X asserted knew of the insured's pre-existing illness. The Court noted that Mr. B was employed by Y Company as a "diplomat" or "external affairs staff member" (外交員 - gaikōin). This term was commonly used in that era to refer to field agents, canvassers, or solicitors whose primary job was to find potential customers and encourage them to apply for insurance.

The Daishin-in determined, based on the findings of the lower court which it found acceptable, that Mr. B's authority as such a solicitor was specifically limited to the following functions:

- Soliciting individuals to apply for insurance policies offered by Y Company.

- Acting as an intermediary in forwarding completed insurance applications from potential clients to the company.

- Receiving insurance premium payments on behalf of the insurer.

Crucially, the Daishin-in held that Mr. B did not possess the qualification or the legal authority to receive, on behalf of Y Company, formal and binding disclosures from applicants concerning material facts such as pre-existing medical conditions.

Whose Knowledge Matters for Imputing Knowledge (or Negligent Ignorance) to the Insurance Company?

The Daishin-in then laid down a general principle for determining whether an insurance company, at the time it concludes a life insurance contract, can be legally deemed to have "known" material facts relevant to assessing the risk to the insured's life, or can be considered to have been "negligent in not knowing" such facts. (Under the Commercial Code at the time, if an insurer knew, or was negligent in not knowing, a material fact that the applicant failed to disclose, the insurer typically lost its right to later rescind the policy based on that non-disclosure).

The Court stated that such legally relevant knowledge (or negligent ignorance) on the part of the insurance company is to be determined by reference to the knowledge or actions of specific individuals who are duly authorized to act for the company in these particular capacities:

- The physician who medically examined the insured's health status on behalf of the insurance company (if such an examination was part of the application process).

- OR, a person specifically authorized by the insurance company to receive formal disclosure of such material facts from the insured applicant or policyholder (this would typically refer to personnel in the underwriting department or other specifically designated officials).

- OR, a person within the insurance company who directly participated in the decision-making process regarding whether to accept the application and conclude the contract (i.e., underwriters or other relevant decision-makers).

A Solicitor's Personal Knowledge is Insufficient for Legal Imputation to the Company

Applying this principle, the Daishin-in concluded:

A person who is merely an insurer's field solicitor – whose authority is confined to soliciting applications, acting as an intermediary in processing those applications, and receiving premium payments – even if that solicitor personally knew of material facts (such as Mr. A's pre-existing mental illness in this case, perhaps due to living in the same village or from general community knowledge), cannot have their personal, informal knowledge automatically imputed to the insurance company as a whole.

The solicitor's individual awareness of such facts, if not communicated through the proper, formal channels to those within the company who are authorized to receive and act upon such information for underwriting purposes, does not, in itself, legally establish that the insurer as an entity acted with "intent" (i.e., that the company had actual, official knowledge of the undisclosed fact) or that it acted with "negligence" (in not knowing those facts).

Outcome of the Appeal

Since Mr. B, the solicitor, was found to lack the specific authority to receive legally binding disclosures of medical conditions on behalf of Y Company, his personal knowledge of Mr. A's long-standing mental illness could not be legally attributed to Y Company for the purpose of preventing rescission. As Mr. A had failed to disclose this material pre-existing condition through channels that would have formally and legally bound the company (for example, by stating it on the application form itself, or by disclosing it to an examining physician if one had been involved and had the authority to receive such information – a point explored in other Daishin-in cases), Y Company was within its rights to rescind the policy upon discovering the non-disclosure after Mr. A's death.

Therefore, the Daishin-in found Mr. X's appeal to be without merit and dismissed it.

Analysis and Implications of this Early Ruling

This 1934 Daishin-in judgment, though rendered nearly a century ago, is a significant case in the historical development of Japanese insurance law. It played a role in defining the limited scope of an insurance solicitor's agency authority, particularly in the context of the crucial duty of disclosure in life insurance.

1. Establishing Boundaries for a Solicitor's Agency:

The decision established a clear, albeit somewhat restrictive from the policyholder's viewpoint, presumption regarding the authority of insurance solicitors. It positioned them primarily as agents for the purpose of sales and application processing, rather than as agents empowered to receive legally binding disclosures of material facts that would automatically impute knowledge to the insurance company's underwriting functions. This set an early precedent that influenced how the roles and responsibilities of field sales staff were understood in the Japanese insurance industry for many decades.

2. Emphasizing the Importance of Formal Disclosure Channels:

The ruling implicitly and strongly underscored the importance for applicants for life insurance (and for those seeking to revive lapsed policies) to ensure that all material information, especially concerning their health and medical history, is disclosed through the formal channels prescribed or recognized by the insurance company. In that era, this typically meant accurately and completely filling out the written application form and making full disclosure to the insurer's appointed medical examiner, if a medical examination was part of the underwriting process. Relying solely on oral disclosure to a soliciting agent, or assuming that an agent's personal knowledge of a condition would suffice, was deemed insufficient to bind the company if that agent lacked the specific authority to receive such disclosures for underwriting purposes.

3. Distinguishing the Role of a Solicitor from That of an Examining Physician:

While this particular 1934 judgment focused specifically on the limited authority of the solicitor, it is useful to view it in the context of other early Daishin-in rulings that dealt with different types of insurer representatives. For instance, as legal commentary (such as the PDF provided with this case) often points out, a Daishin-in decision from 1916 (the case from h59.pdf, which was the subject of a previous blog post in this series) took a notably different stance regarding the authority of an examining physician appointed by the insurer. That earlier case held that an insurer's examining physician does act as an "organ of the company" and possesses the authority not only to receive material medical disclosures from applicants but also to exercise professional judgment regarding the materiality of those disclosed facts and to decide whether they need to be formally recorded on the application. Such knowledge acquired and judgments made by the examining physician were held to be binding on the insurance company. The 1934 judgment's more restrictive view of the solicitor's authority serves to highlight this important legal distinction between different types of representatives with whom an applicant might interact.

4. Historical Context: Protecting Insurers in an Early and Developing Market:

This ruling was delivered during a relatively early period in the development of the modern life insurance market in Japan. From one perspective, the decision can be seen as somewhat insurer-protective. By placing a significant onus on applicants to ensure formal disclosure through designated channels, and by limiting the extent to which informal knowledge held by a field sales force could be imputed to the company, the Daishin-in's approach arguably helped insurers manage underwriting risks in an era where information flows and agency controls might have been less standardized or robust than they are today.

5. The Traditional Doctrine of "Gaimuin no Sanmuken" (The Solicitor's "Three No-Powers"):

Legal commentators often place this judgment within the context of a traditional, though frequently criticized, understanding in Japanese insurance practice known as the "solicitor's three no-powers" (gaimuin no sanmuken). This uncodified doctrine generally held that insurance solicitors typically lacked: (1) the power to unilaterally conclude insurance contracts on behalf of the company; (2) the power to receive insurance premiums (though, interestingly, the Daishin-in in this specific 1934 case did acknowledge that the solicitor, Mr. B, did have authority to receive premiums on behalf of the insurer); and (3) the power to receive legally binding disclosures of material facts from applicants. While this doctrine was often criticized by legal scholars for its potential to create unfair outcomes for policyholders who might reasonably rely on the words or perceived authority of the soliciting agent they dealt with, it reflected a common insurer stance and was, to some extent, supported by certain lines of case law, including this 1934 decision.

6. Evolution of Japanese Insurance Law – The Modern Context:

It is absolutely crucial to view this 1934 Daishin-in judgment within its specific historical context. Japanese insurance law and practice have undergone very significant evolution and modernization since that time, culminating in the enactment of a comprehensive, standalone Insurance Act in 2008 (which came into full force in 2010), as well as numerous revisions to the Insurance Business Law which governs the conduct of insurers and intermediaries.

- Today, Japan's Insurance Act (e.g., in Article 37) frames the duty of disclosure primarily as a duty to truthfully answer specific questions posed by the insurer during the application process (this is often referred to as a "question-response duty" - 質問応答義務, shitsumon ōtō gimu). This is a notable shift from the system under the old Commercial Code, which was often interpreted as imposing a more general, spontaneous duty on the applicant to disclose all facts they thought might be material, whether specifically asked about or not.

- Furthermore, the current Insurance Act (e.g., in Article 55, Paragraph 2, Items 2 and 3) now contains explicit provisions that can bar an insurer's right to rescind a policy for non-disclosure or misrepresentation if the insurer's own solicitor or agent actively obstructed the applicant from making a proper disclosure or incited them to make a non-disclosure or a misrepresentation. These modern statutory provisions provide a much stronger level of policyholder protection against misconduct by insurance intermediaries than was explicitly available under the legal framework of 1934.

- While the fundamental principle that a solicitor's mere personal knowledge of a fact might not always, in every circumstance, automatically and without further inquiry bind the insurance company (if that knowledge was never conveyed to the underwriting department and the solicitor lacked specific authority) may still hold some residual resonance, the modern legal landscape, with its much greater emphasis on insurer duties of explanation, fair conduct in solicitation, and the specific liabilities for intermediary misconduct, would undoubtedly lead to a far more nuanced and potentially more policyholder-protective analysis if a case with facts analogous to this 1934 Daishin-in decision were to arise today.

Conclusion

The Daishin-in's 1934 decision in this life insurance case stands as an important historical landmark in the development of Japanese insurance law. It provided an early and influential pronouncement on the limited nature of an insurance solicitor's (or "external affairs staff member's") authority to receive, on behalf of the insurance company, legally binding disclosures of material facts, such as an applicant's pre-existing medical conditions.

The Court clearly held that a solicitor's authority is generally presumed to be confined to tasks such as soliciting applications for insurance, acting as an intermediary in forwarding those applications to the company, and, in some instances, receiving premium payments. Their personal, informal knowledge of an applicant's undisclosed health conditions was not, under the legal framework of the time, automatically imputed to the insurance company in such a way as to prevent the insurer from later rescinding the policy for that non-disclosure, provided the disclosure was not made through other proper channels (such as to an examining physician with clear authority, or by being accurately recorded on the formal application form).

The Daishin-in emphasized that for an insurer to be legally deemed to have "known" material facts (or to have been "negligent in not knowing" them, which would bar its right to rescind under the old Commercial Code for non-disclosure), such knowledge or negligence must generally be attributable to individuals within the insurance company who possess the proper authority to receive and act upon such critical underwriting information – typically, the company's examining physicians or those directly involved in the contractual decision-making and underwriting process.

While this judgment reflects the legal interpretations and insurance practices of its era, and while Japanese insurance law has undergone substantial evolution and modernization since 1934 (particularly with the enactment of the 2008 Insurance Act, which includes more explicit protections for policyholders regarding the actions of insurance intermediaries), this early Daishin-in ruling remains a significant historical reference point. It helps to illuminate the traditional Japanese legal view on the division of roles and authorities in the life insurance application and disclosure process, and it highlights the long-standing importance attached to formal disclosure channels and the historically limited agency powers that were typically attributed to field sales staff for core underwriting matters.