A Shot in Error, A Shot in Mercy: Japan's Supreme Court on Negligence, Intent, and a Single Death

Decision Date: March 22, 1978

Case Name: Professional Negligence Resulting in Injury, Murder, and Abandonment of a Corpse

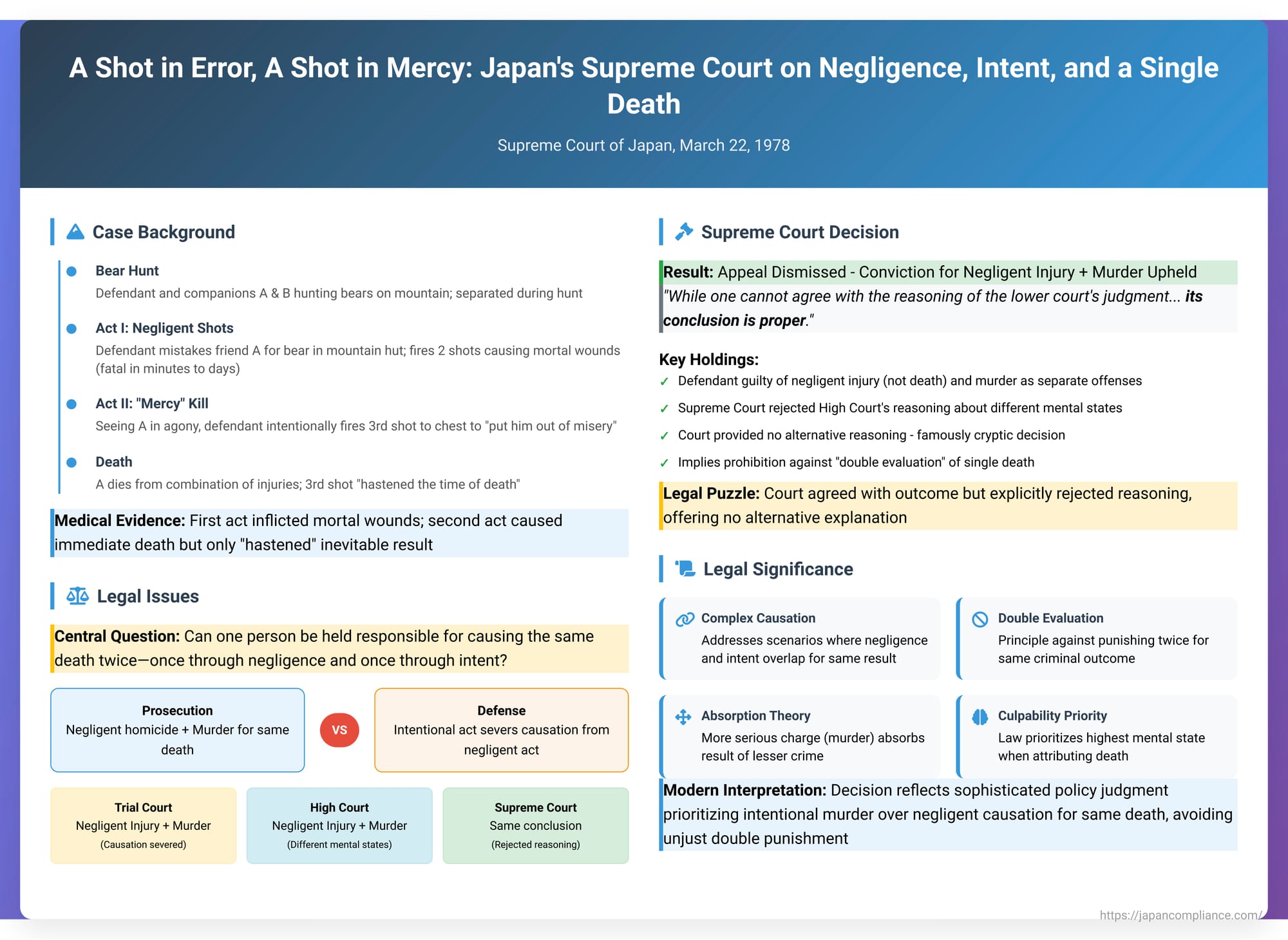

Legal hypotheticals are often designed to test the absolute limits of legal principles. But on rare occasions, a real case emerges that is so bizarre, so tragic, and so legally complex that it surpasses any textbook scenario. Such is the case of a fateful bear hunt that ended in a puzzling sequence of events, culminating in a landmark—and famously enigmatic—decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on March 22, 1978.

The case forces a confrontation with a fundamental question of causation: What happens when a person's initial negligent act creates a fatal situation, and that same person then commits a second, intentional act to bring about the already inevitable death? Does the second, deliberate act of murder sever the causal link from the first negligent act? Or can a single person be held responsible for causing the same death twice, once through negligence and once through intent? The Supreme Court's answer, or rather its lack of a detailed one, has fueled legal debate for decades and reveals a deep-seated principle in Japanese jurisprudence concerning culpability and the attribution of consequences.

The Facts of the Case: A Tragedy in Two Acts

The incident began on a mountain, where the defendant, along with two companions, A and B, set out to hunt for bears. The facts, as established by the lower courts, unfolded in two distinct acts.

Act I: The Negligent Shooting

After separating from his companions, the defendant was searching for A. He spotted a black shadow moving inside a mountain hut. In a moment of grave misjudgment, he concluded the shadow was a bear when, in reality, it was his friend, A. The defendant fired two shots from his hunting rifle in quick succession, striking A and causing serious injuries.

The medical evidence was crucial. The first act of shooting inflicted two significant wounds:

- One wound to the lower abdomen, which, if left untreated, would have been fatal in two to three days.

- A second wound to the right groin, which was untreatable and would have caused death within a matter of minutes to a few tens of minutes.

Critically, the defendant's first negligent act had already inflicted a mortal wound. A's death was already a certainty.

Act II: The Intentional "Mercy" Killing

Seeing A in agony, the defendant made a chilling decision. He resolved to kill A to "put him out of his misery". With this clear homicidal intent, he aimed his rifle at A's right chest and fired a single shot. This second act caused A's death.

The medical assessment of this third wound was that, on its own, it would have been fatal within a day if left untreated. In the context of the existing injuries, its effect was to "hasten the time of death".

The Legal Labyrinth: From Trial Court to Supreme Court

The prosecution charged the defendant with Professional Negligence Resulting in Death for the first act, and Murder for the second. The legal journey of the case reveals the complexity of this scenario.

The Trial Court (First Instance): Causation Severed

The trial court found the defendant guilty of Professional Negligence Resulting in Injury and Murder, treating them as separate, cumulative offenses (heigōzai). The court refused to convict for causing death through negligence. Its reasoning was direct: A had not yet died from the first set of injuries when he was killed by the defendant's second, intentional act. Therefore, the court reasoned, "the causal progression from the first act must be assessed as having been severed by this [second act]". In this view, the defendant's own subsequent murder broke the chain of causation from his initial negligence.

The High Court (Second Instance): Affirming the Conclusion

The appellate court upheld the trial court's conclusion, though its reasoning differed slightly. It agreed that the defendant was guilty of Professional Negligence Resulting in Injury and Murder as separate offenses. The High Court focused on the change in the defendant's mental state (mens rea), positing that the criminal conduct up to the point of the murder was negligence, and after that point, it was purely intentional murder. Because negligence and intent are different conditions of responsibility, the court held they should be treated as cumulative offenses. The defendant's appeal was dismissed.

The Supreme Court's Enigmatic Decision

The case finally reached the Supreme Court, which issued an exceptionally brief decision. It dismissed the final appeal, affirming the lower court's conclusion. However, in a cryptic addendum—a hallmark of many complex Japanese judicial opinions—the Court added:

"Additionally, while one cannot agree with the reasoning of the lower court's judgment on the number of crimes, which held that the crime of professional negligence resulting in injury and the crime of murder should be understood as cumulative offenses because their conditions of responsibility differ, its conclusion is proper."

This created a legal puzzle. The Supreme Court agreed with the outcome (guilty of negligent injury and murder) but explicitly rejected the High Court's reasoning. Yet, it offered no alternative reasoning of its own. It simply stated the conclusion was correct. The decision implicitly confirms that the first act did not legally constitute a "homicide," only an "injury," but fails to explain why. This has left legal scholars to deconstruct the unstated logic that justifies this conclusion.

Deep Dive: Reconstructing the Court's Unspoken Rationale

The central question is how the Supreme Court could justify convicting for only negligent injury when the defendant's negligent act was, in fact, fatal. Two main lines of reasoning emerge from scholarly analysis of the decision.

Theory 1: The "Broken Causation" Argument (and its Flaws)

The simplest explanation is that the Supreme Court, like the trial court, believed that the defendant's own supervening, intentional act of murder broke the causal link from his initial negligent act. According to this logic, the free and deliberate choice to kill A legally displaces the earlier, accidental cause.

However, this theory runs into significant problems when compared with other key Supreme Court precedents. Most notably, the famous "Osaka Nanko Case" (Decision of the Supreme Court, Nov. 20, 1990) established that when a defendant's assault creates a fatal injury, the causal link to the death is not broken even if a third party later commits another act that "hastens the time of death".

The inconsistency is glaring. If an intervening intentional act by a third party does not sever causation, why should an intervening intentional act by the original actor himself sever it? The logic seems inconsistent. Furthermore, from the perspective of modern causation theories like "realization of risk," the defendant's first act created a lethal danger, and the victim's death was a direct realization of that danger. The first act was, by itself, sufficient to cause death. To deny the causal link seems to contradict the physical reality of the situation.

Theory 2: The Prohibition of "Double Evaluation"

A more sophisticated and compelling explanation centers on the legal principle prohibiting "double evaluation" or "double jeopardy" regarding a single result. This principle holds that the legal system should not punish an individual twice for the same criminal outcome. In this case, there is only one death. To convict the defendant of both causing that death through negligence and causing it through murder would be to hold him criminally responsible for the same result under two separate charges. This would be unjust.

To avoid this "double evaluation," the court performs a kind of legal triage. It attributes the single result—the death of A—to the most proximate and, crucially, the most culpable act: the intentional murder. The lesser crime of negligence is effectively pushed aside in the causal accounting for the death. The law, in this view, does not deny that the first act was factually a cause of death. Rather, as a matter of legal policy, it chooses to attach the consequence of death exclusively to the more serious, intentional crime.

This approach neatly explains the court's conclusion without creating the logical inconsistencies of the "broken causation" theory.

The "Absorption" Theory: A Synthesis

The most refined version of this logic is sometimes described as an "absorption" or "subsumption" theory. It works as follows:

- Causation is Affirmed (Factually): First, the law acknowledges the reality that the defendant’s first negligent act did, in fact, create a sufficient causal link to the victim's death.

- The Result is "Absorbed" (Legally): For the purpose of determining the number of crimes and sentencing, the single outcome of death is legally "absorbed" into the more serious crime of murder. The greater charge subsumes the result of the lesser one.

- The Final Tally: This leaves the defendant guilty of (a) the non-fatal component of his first act, which is Professional Negligence Resulting in Injury, and (b) his second act, which is Murder (and which carries the full legal weight of causing the death).

This framework has the advantage of aligning with legal precedent and theory, while still reaching the Supreme Court's conclusion. It shows that the Court’s decision was likely not about a mechanical application of causation rules, but a sophisticated policy judgment aimed at achieving a just outcome without violating the principle against double punishment.

However, this approach is not without its own theoretical problems. As some commentators have noted, what if the prosecutor had chosen, for some reason, to only charge the defendant with negligent homicide for the first act and not to prosecute the second act as murder? If the death is legally "absorbed" into a murder charge that is never brought, the defendant could paradoxically be acquitted of causing death altogether, even though his negligent act was fatal. This highlights that while the absorption theory provides the most coherent explanation for the Court's decision, it remains a pragmatic judicial construction rather than a universally seamless doctrine.

Conclusion: A Judgment on Culpability, Not Just Causation

The 1978 "Hunter's Choice" case remains a vital lesson in Japanese criminal law. It demonstrates that causation is not always a simple, linear analysis of physical cause and effect. When multiple acts by a single person with different mental states contribute to one result, the law must do more than trace the chain of events. It must make a judgment about how to attribute legal responsibility in a way that is fair and proportional to the actor's culpability.

The Supreme Court’s cryptic ruling, when unpacked, suggests a clear preference: in the face of a single death, the ultimate legal responsibility should attach to the moment of highest culpability—the moment of clear, murderous intent. The decision is less a statement that negligence cannot cause death in such circumstances, and more a policy statement that murder, as the graver offense, takes precedence in accounting for the final, tragic result. It is a powerful illustration of how the law prioritizes a defendant's state of mind to resolve one of the most complex causal paradoxes imaginable.