A Second Chance to Prove Use: Japan's Supreme Court on Evidence in Non-Use Trademark Cancellation Appeals (Chez Toi Case)

Judgment Date: April 23, 1991

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Case Number: Showa 63 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 37 (Action for Rescission of a Trial Decision)

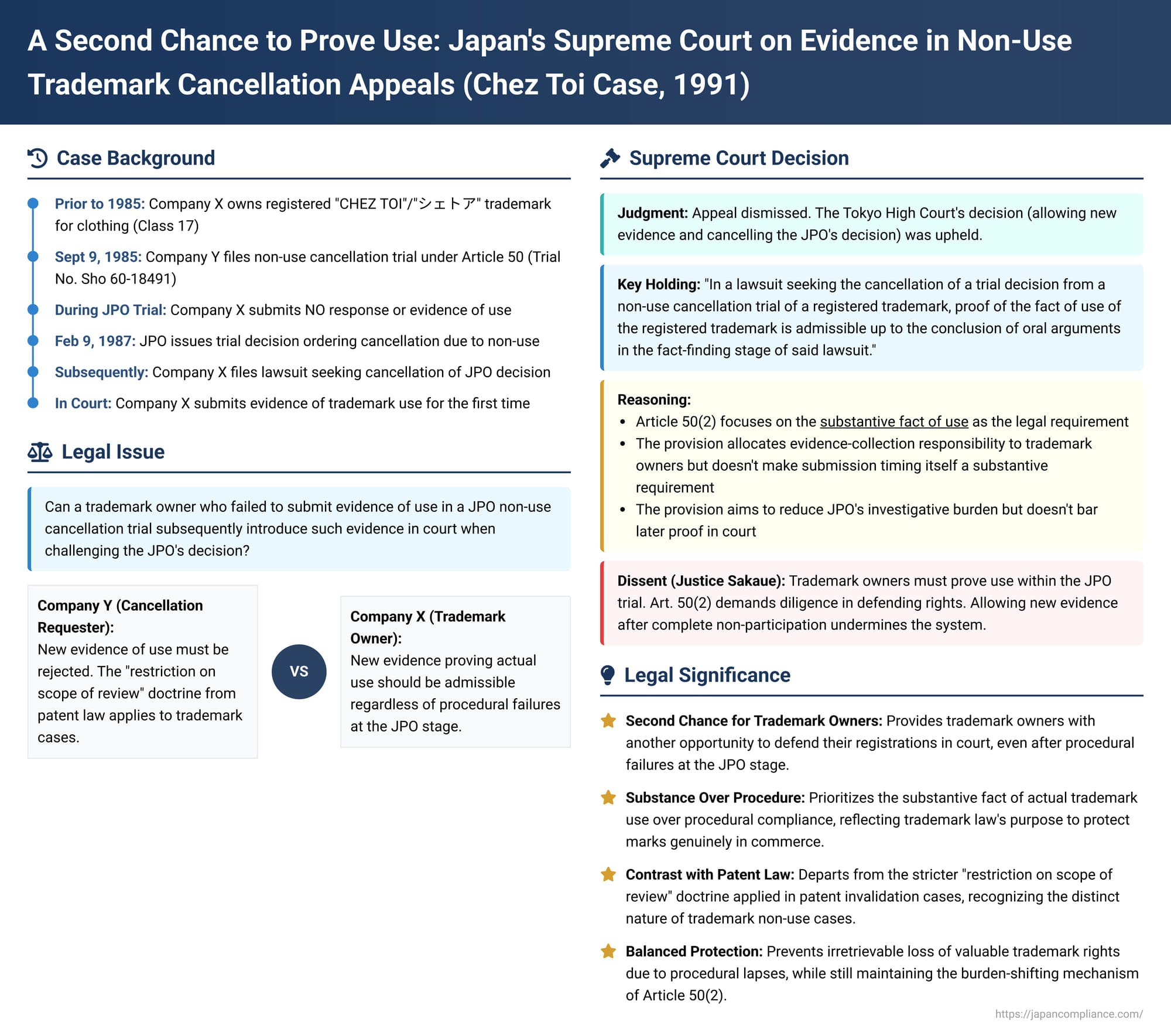

The "Chez Toi" (シェトア) case, decided by the Japanese Supreme Court in 1991, addressed a critical procedural question in trademark law: Can a trademark owner who failed to submit proof of use during a non-use cancellation trial before the Japan Patent Office (JPO)—resulting in a decision to cancel their trademark—subsequently introduce such evidence in a court lawsuit seeking to overturn that JPO decision? The Supreme Court's affirmative answer provided a significant, albeit debated, avenue for trademark owners to defend their registrations, emphasizing the substantive fact of use over procedural lapses at the JPO stage in this specific context.

The Non-Use Cancellation Challenge and Procedural Lapses

The dispute involved Company X, the owner of a registered trademark consisting of the words "CHEY TOI" and its Katakana equivalent "シェトア" (Chez Toi), both written horizontally. The trademark was registered for goods in Class 17, including "clothing (excluding special sportswear), textile personal items (not belonging to other classes), and bedding (excluding beds)."

Company Y initiated a non-use cancellation trial (不使用取消審判 - fushiyō torikeshi shinpan) against Company X's trademark registration on September 9, 1985. Under Japanese Trademark Law (Article 50), if a registered trademark has not been used in Japan for the designated goods or services for a continuous period of three years or more by the trademark owner or a licensee, any person can request a trial for the cancellation of the trademark registration.

The JPO docketed this as Trial No. Sho 60-18491. In a crucial procedural turn, Company X, the trademark owner, submitted no response (答弁 - tōben) whatsoever, nor did it provide any evidence of its trademark's use, during the entire JPO trial proceeding. Consequently, on February 9, 1987, the JPO issued a trial decision (shinketsu) ordering the cancellation of Company X's "CHEY TOI" trademark registration due to non-use. This was in accordance with Article 50, Paragraph 2 of the Trademark Law, which places the burden on the trademark owner to prove use once a non-use cancellation action is initiated.

Dissatisfied with the JPO's cancellation decision, Company X filed a lawsuit with the Tokyo High Court seeking to have the JPO's decision rescinded (審決取消訴訟 - shinketsu torikeshi soshō). In this High Court action, Company X, for the first time, formally asserted that its "CHEY TOI" trademark had indeed been used in Japan on the designated goods within the relevant three-year period prior to the registration of Company Y's cancellation request. Company X proceeded to submit evidence to the court to substantiate this claim of use.

The High Court's Turnaround: Accepting New Evidence of Use

The Tokyo High Court sided with Company X and ordered the cancellation of the JPO's decision. The High Court reasoned that the crucial question in a lawsuit to cancel a JPO non-use cancellation decision is whether the substantive requirements of Article 50, Paragraph 2 (i.e., whether the registered trademark was actually in use) were met as of the time the JPO made its trial decision. The High Court opined that its role was not merely to review whether proof of use had been submitted during the JPO trial proceedings themselves. Since the evidence newly presented to the court clearly demonstrated that the "CHEY TOI" trademark had, in fact, been used during the relevant period, the High Court concluded that the JPO's decision (which was premised on the non-recognition of such use because no proof was offered to it) was substantively incorrect and unlawful at the time it was rendered and should therefore be cancelled.

Company Y, the original cancellation requester, appealed the Tokyo High Court's decision to the Supreme Court. Company Y's main argument was that the High Court had erred by admitting and considering new evidence of use that was not presented during the JPO trial. Company Y cited a 1976 Supreme Court Grand Bench decision concerning patent invalidity trials (the Meriyasu Amiki Jiken or Knitting Machine Case), which generally restricts the introduction of new invalidity grounds or new evidence in lawsuits appealing JPO patent trial decisions. Company Y contended that this principle should also apply to trademark cancellation cases.

The Supreme Court's Affirmation: Proof of Use Admissible in Court

The Supreme Court dismissed Company Y's appeal, thereby upholding the Tokyo High Court's decision allowing Company X to introduce new evidence of use at the court stage.

The Majority Opinion's Core Holding:

The Supreme Court declared: "In a lawsuit seeking the cancellation of a trial decision from a non-use cancellation trial of a registered trademark, proof of the fact of use of the registered trademark (within the three years prior to the registration of the cancellation request) is admissible up to the conclusion of oral arguments in the fact-finding stage of said lawsuit."

Reasoning Regarding Trademark Law Article 50(2):

The Court closely analyzed Article 50, Paragraph 2 of the Trademark Law. This provision states that in a non-use cancellation trial, unless the trademark owner (the respondent) proves that the registered trademark has been used, the trademark registration cannot escape cancellation. The Supreme Court interpreted this as follows:

- The substantive legal requirement for avoiding cancellation is the actual fact of use of the registered trademark.

- Article 50(2) serves a procedural purpose: it allocates a share of the responsibility for collecting evidence of this factual use to the trademark owner. This is intended to reduce the burden on the JPO trial examiners who might otherwise have to conduct extensive ex officio investigations (職権による証拠調べ - shokken ni yoru shōko shirabe) to ascertain use.

- Crucially, the provision does not mean that the act of the trademark owner proving use at the specific time of the JPO trial decision is itself the substantive requirement for avoiding cancellation. The core requirement is the existence of use; the proof is the means to demonstrate it.

Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that Article 50(2) does not bar a trademark owner from submitting proof of use for the first time in a subsequent court action reviewing the JPO's cancellation decision.

The Court did not explicitly address Company Y's reliance on the Meriyasu Amiki patent case, but the implication was that the stricter rules regarding new evidence in patent invalidity appeals might not directly translate to the specific context of trademark non-use cancellations, given the differing nature of the issues and proofs involved.

Justice Sakaue's Dissenting Opinion: A Call for Diligence at the JPO Stage

Justice Sakaue issued a strong dissenting opinion, disagreeing with the majority's interpretation and its conclusion.

- He argued that the primary purpose of Article 50, Paragraph 2 was to promote the active protection and utilization of trademarks and, importantly, to facilitate the elimination of "dormant trademark rights" (休眠商標権 - kyūmin shōhyōken).

- The requirement for the trademark owner to prove use was, in his view, a legislative demand for sincere and diligent engagement by the trademark owner in the JPO trial proceedings to defend their own rights. The majority's point about reducing the JPO's evidentiary burden was merely a consequence of this primary demand for diligence.

- Justice Sakaue emphasized that trademark owners are granted exclusive rights (under Trademark Law Article 25) and are uniquely positioned to know and easily prove the facts of their own trademark use.

- Therefore, he believed the true legislative intent (法意 - hōi) of Article 50, Paragraph 2 was that the trademark owner must prove the fact of use within the JPO trial itself if they wish to avoid cancellation.

- He argued that an interpretation allowing new proof of use to be introduced for the first time in court, especially in a case like this where the trademark owner (Company X) had not even bothered to respond or submit any evidence during the JPO trial, should not be adopted.

- In his view, Company X had completely failed to meet the procedural expectations set by the law. Therefore, the High Court had erred in allowing new evidence and overturning the JPO's decision, and its judgment should have been reversed, and Company X's claim dismissed.

Understanding the Legal Context and Significance of the Ruling

The "Chez Toi" decision is significant for its interpretation of procedural fairness and evidentiary rules in the specific context of non-use trademark cancellations.

- Purpose of the Non-Use Cancellation System (Article 50): The underlying policy of Japan's non-use cancellation system is that trademark protection is fundamentally intended for marks that are actively used in commerce and have thereby accumulated goodwill. Registrations for marks that are not used ("deadwood") are considered detrimental because they can unfairly block others from using or registering similar marks for their own legitimate business purposes, thereby narrowing the field of available trademarks.

- Shift in the Burden of Proof: A crucial historical context is the 1975 amendment to the Trademark Law. Before this amendment, the burden of proof in a non-use cancellation trial rested on the party requesting the cancellation to prove the difficult fact of non-use. This proved to be an almost insurmountable hurdle, rendering the cancellation system largely ineffective. The 1975 amendment rectified this by shifting the burden: once a cancellation request is filed, the trademark owner (the respondent) must affirmatively prove that the mark has been used (Article 50(2)).

- The "Restriction on Scope of Review" Doctrine: Company Y's appeal to the Supreme Court heavily relied on a doctrine well-established in Japanese patent law, often referred to as the "restriction on the scope of review" (審理範囲の制限 - shinri han'i no seigen). This doctrine, notably articulated in the 1976 Meriyasu Amiki Supreme Court Grand Bench decision, generally holds that in lawsuits seeking to cancel JPO trial decisions in patent cases (e.g., invalidity trials), the court's review is limited to the specific grounds and evidence that were presented and considered during the JPO trial. New arguments or new evidence (like different prior art references) typically cannot be introduced for the first time at the court stage. This principle is generally understood to apply to trademark invalidity trials as well.

- Why a Different Approach for Non-Use Cancellations? The Supreme Court in Chez Toi, by allowing new evidence of use, chose not to apply this strict "restriction on scope of review" doctrine to trademark non-use cancellation appeals. The PDF commentary suggests a key reason for this distinction lies in the potentially severe and irreversible consequences for the trademark owner.

- In patent invalidity, if a specific piece of prior art is barred from consideration in one court case due to procedural rules, the patent might still be challenged later on other grounds or by different parties. The fight over validity can be multifaceted.

- However, in a non-use cancellation, the core issue is the simple factual question of whether the mark was used. If a trademark owner is barred from presenting proof of actual use in court merely because of a procedural misstep at the JPO stage (especially if, as here, they entirely failed to participate), they would lose their trademark right definitively and perhaps unfairly, even if the mark was genuinely in use. The outcome is more binary and potentially harsher.

- Furthermore, proving trademark use is often a matter of demonstrating the trademark owner's own commercial activities, which is arguably less complex and more within the court's traditional fact-finding capabilities than evaluating highly technical prior art in patent disputes, where the JPO's specialized expertise is more central.

- Meaning of "Fact of Use" for Evidentiary Submissions: The Supreme Court's decision allows for the "proof of the fact of use." This is interpreted by commentators to mean the general, abstract fact that the registered trademark was indeed used as required by law, not limited to specific instances of use that might have been (or, in this case, were not) argued before the JPO. Consequently, under this ruling, a trademark owner can introduce entirely new concrete evidence of qualifying uses in court, even if no such specific uses were mentioned or substantiated during the JPO trial.

Implications of the Chez Toi Ruling

The Chez Toi decision has had significant implications:

- Increased Flexibility for Trademark Owners: It provides trademark owners with a "second chance" to defend their registrations in court if they can produce valid evidence of use, even if they failed to adequately present their case (or present it at all) during the JPO's non-use cancellation trial. This can be seen as prioritizing the substantive question of actual use over strict procedural compliance at the administrative level for this type of cancellation.

- Focus on Substantive Use: The ruling reinforces the idea that the ultimate determinant in a non-use cancellation scenario is whether the trademark was, in fact, being used. The procedural requirement under Article 50(2) for the trademark owner to prove use is an evidentiary tool, not an absolute bar if proof is later forthcoming in court.

- Potential Impact on JPO Proceedings: While offering a safety net, the ruling could also, as Justice Sakaue's dissent feared, reduce the incentive for trademark owners to fully and diligently participate in the JPO's non-use cancellation trials, knowing they might be able to introduce evidence later in court. This could potentially affect the efficiency of the JPO's administrative process.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment in the "Chez Toi" case marks a key point in Japanese trademark law concerning the procedural handling of non-use cancellation challenges. By permitting trademark owners to submit new proof of trademark use during a lawsuit to cancel a JPO decision, even if such proof was not tendered at the JPO stage, the Court prioritized the substantive question of whether a mark was genuinely in use over strict adherence to procedural timelines within the administrative trial. While Justice Sakaue's dissent raised valid concerns about procedural diligence, the majority opinion provides a significant safeguard for trademark owners, ensuring that valuable trademark rights are not irretrievably lost due to procedural omissions at the JPO level, provided that the fundamental requirement of actual use can ultimately be established in court. This decision reflects a balance, albeit one that has generated debate, between procedural order and the protection of substantive rights based on real-world commercial activity.