A Question of Choice: The Japanese Supreme Court on Informed Consent in Childbirth

Date of Judgment: September 8, 2005

Case Reference: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, 2002 (Ju) No. 989

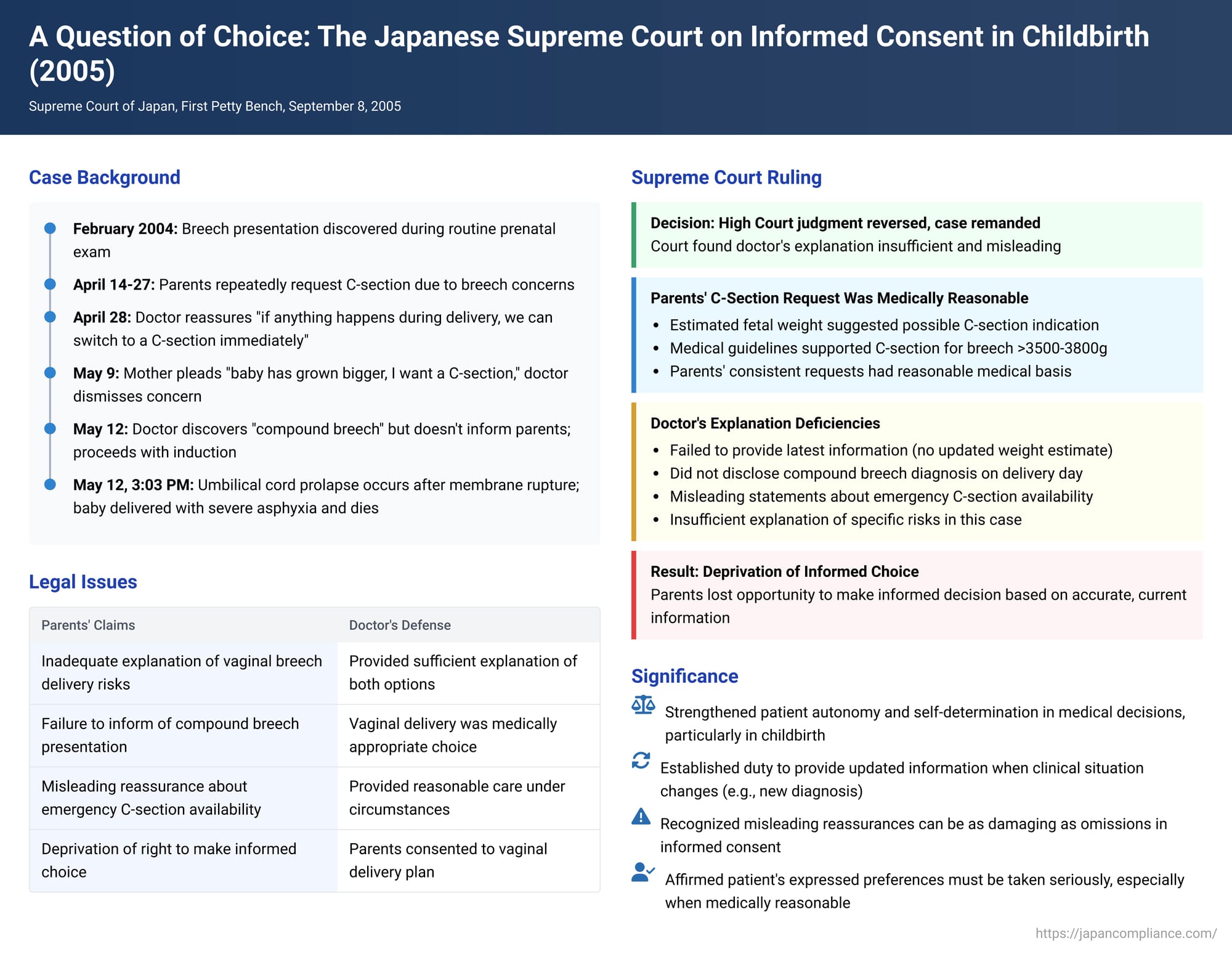

This article delves into a significant decision by the Supreme Court of Japan, delivered on September 8, 2005, which underscores the critical importance of a physician's duty to provide comprehensive and accurate information to patients, thereby enabling them to make truly informed decisions about their medical care. The case revolves around a tragic childbirth scenario where a couple's repeated requests for a Cesarean section for a breech presentation were met with reassurances and a course of action that ultimately led to the loss of their newborn. The Court's ruling meticulously examines the scope and nature of the doctor's duty of explanation, particularly when alternative medical procedures exist and patient preferences are clearly articulated.

The Factual Background: A Couple's Journey and Growing Concerns

The case involved a married couple, Mr. X1 and Mrs. X2. In August of Year 3 (Heisei 5), Mrs. X2, then 31 years old and pregnant for the first time, began receiving prenatal care at B Hospital. Her physician was Dr. Y1. Her due date was estimated to be May 1 of Year 4 (Heisei 6).

On February 9, Year 4, a significant development occurred: an examination revealed that the fetus was in a breech presentation. This means the fetus was positioned with its head towards the top of the uterus (fundus) and its buttocks or feet towards the cervix (birth canal opening), as opposed to the more common cephalic (head-first) presentation.

Dr. Y1 conducted further assessments. On April 13 (at 37 weeks and 3 days of gestation), based on an internal examination and X-ray pelvimetry, Dr. Y1 concluded that at the time of delivery, the fetus would likely be in a "buttocks presentation" (殿位 - den'i, where the buttocks descend first). He determined that Mrs. X2's pelvic size and shape were adequate, and there were no factors like cephalopelvic disproportion (mismatch between fetal head size and maternal pelvis) that would complicate a vaginal delivery. Consequently, Dr. Y1 informed Mrs. X2 that a vaginal delivery was feasible and that this would be the planned approach.

However, Mr. and Mrs. X1 were understandably anxious about a vaginal delivery for a breech presentation. On April 14, they communicated their strong preference for a Cesarean section (C-section) to Dr. Y1. Mrs. X2 reiterated this request during her check-up on April 20. In response, Dr. Y1 explained that, based on his assessment, vaginal delivery was possible. He also outlined potential risks associated with a C-section, such as issues with surgical wound healing or the risk of uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies. He advised them to discuss the matter further as a family.

Undeterred, Mrs. X2 again expressed her wish for a C-section during her appointment on April 27. Dr. Y1 sought to reassure her, stating that they could switch to a C-section in any eventuality if problems arose, implying there was no cause for concern. On this same day, Dr. Y1 performed an ultrasound, estimating the fetal weight at 3057 grams. Combined with his internal examination findings, he maintained his judgment that the presentation at birth would be buttocks-first. Notably, Dr. Y1 did not perform any further estimations of fetal weight after this April 27 assessment.

The following day, April 28, Mrs. X2 was admitted to B Hospital for childbirth. Dr. Y1 provided Mr. and Mrs. X1 with an explanation covering the typical course of a vaginal breech delivery and the risks associated with a C-section. He also mentioned specific risks pertinent to breech presentation, such as the possibility of umbilical cord prolapse (where the cord slips down ahead of the baby) if the amniotic sac (waters) broke prematurely, which could endanger the fetus if not managed promptly, potentially necessitating an emergency C-section. The couple perceived that this information was delivered with a tone that clearly favored and recommended vaginal delivery.

During this discussion, Mrs. X2 voiced a specific fear: "I've heard that with a breech baby, the umbilical cord can get caught, so I request a C-section." Dr. Y1 responded with strong, definitive, and, as events would later prove, misleading reassurances: "If you can't give birth under these conditions, you wouldn't be able to even if it were head-first. Even if the baby gets stuck in the birth canal, I can put my hand in its mouth and pull its chin, and it will come out right away. If anything happens during delivery, we can switch to a C-section immediately, so there's nothing to worry about."

Mr. X1, still deeply concerned, pressed further: "Nevertheless, we are still worried, so please don't hesitate to perform a C-section. We are willing to sign the consent form for surgery in advance." Dr. Y1 dismissed their anxieties as excessive and did not take them up on their offer to pre-sign consent.

Time passed, and Mrs. X2 went beyond her due date. On May 9 (at 41 weeks and 1 day of gestation), after an internal examination revealed some signs of cervical ripening (opened to one finger's breadth), Dr. Y1 informed Mrs. X2 that labor would be induced starting May 11. Mrs. X2 once again pleaded for a C-section: "I think the baby has grown bigger. I don't have the confidence to deliver vaginally from below. I would like to have a C-section." Dr. Y1 responded by stating that a fetus does not typically grow significantly after the due date.

The Tragic Delivery

On May 11, in the afternoon around 3:20 PM, Dr. Y1 inserted a balloon bougie (a device to help dilate the cervix) into Mrs. X2's cervix to begin the induction process. Fetal heart rate monitoring commenced around 7:20 PM.

On the morning of May 12, from 6:00 AM to 8:00 AM, Mrs. X2 was given oral doses of a labor-inducing medication every hour. At approximately 8:00 AM, Dr. Y1 performed an internal examination. He felt the fetus's buttocks and heel. This led him to a new, more specific diagnosis regarding the fetal presentation: it was a "compound breech presentation" (複殿位 - fukuden'i). This meant that not only were the buttocks presenting, but one or both feet were also flexed at the knees, with the heels near the buttocks, descending alongside the primary presenting part. Despite this change from his initial assessment of a simple buttocks presentation, and the potentially increased complexity associated with a compound presentation, Dr. Y1 determined that since the cervix was softening, they would proceed with vaginal delivery. Critically, he did not inform Mr. or Mrs. X1 of this updated diagnosis of a compound breech presentation. He then started an intravenous drip of a labor-inducing drug.

Labor progressed throughout the day. By 1:18 PM, contractions were occurring roughly every two minutes. By 3:03 PM, the amniotic sac (bag of waters) became visible at the vaginal opening (a state known as 胎胞排臨 - taihō hairin), but the membranes were strong and did not rupture spontaneously. To avoid a prolonged labor, Dr. Y1 decided to perform an artificial rupture of the membranes (amniotomy).

Immediately upon rupture of the membranes, the umbilical cord prolapsed into the vagina, and the fetal heart rate dropped precipitously—a clear sign of fetal distress. Dr. Y1 attempted to push the prolapsed cord back into the uterus, but his efforts were unsuccessful. At approximately 3:07 PM, he commenced a breech extraction procedure, a manual technique to deliver a breech baby vaginally.

B Hospital was, in fact, equipped to perform emergency C-sections during labor. However, Dr. Y1 made a clinical judgment at that critical moment. He believed that transitioning to a C-section would require at least 15 minutes to deliver the baby, considering the necessary preparations like anesthesia and surgical setup. He concluded that continuing with the vaginal breech extraction would likely result in a quicker delivery and therefore offer a better prognosis for the fetus than an emergency C-section.

At approximately 3:09 PM, Mr. and Mrs. X1's son, A, was born in a state of severe asphyxia (a critical lack of oxygen). A pediatric team, which was on standby, immediately began resuscitation efforts. Despite these measures, baby A tragically passed away at 7:24 PM that evening.

Subsequent information revealed that A's weight at death was 3812 grams. Taking into account the intravenous fluids administered during resuscitation (91.664 ml) and minimal output, it was estimated that A's birth weight was, at most, approximately 3730 grams.

The judgment also provided context on breech deliveries. Vaginal delivery of a breech baby is associated with certain risks compared to a head-first delivery. These include a higher incidence of premature or early rupture of membranes, a longer labor process because the softer, less spherical breech is less effective at dilating the cervix, a higher risk of umbilical cord prolapse (especially with premature rupture of membranes or if the presenting part doesn't fit snugly against the cervix), and an increased likelihood of cord compression between the baby's body and the maternal pelvis during descent. Compression of the cord, particularly as the head (the largest part) is delivered last, can interrupt blood flow and oxygen supply, necessitating rapid delivery to avoid neonatal asphyxia.

Conversely, C-sections, while avoiding some of these risks, are major surgical procedures involving anesthesia and incision, carrying their own set of potential complications for the mother. Therefore, a universal policy of performing C-sections for all breech presentations was not standard practice. The choice between vaginal delivery and C-section for a breech presentation typically involves a comprehensive assessment of various factors: estimated fetal weight, specific type of breech presentation (e.g., frank, complete, footling), maternal pelvic adequacy, gestational age, and the mother's age and obstetric history. Medical literature and guidelines suggested that a C-section was generally indicated for an estimated fetal weight of 3800 grams or more, or for certain types of breech like a footling presentation (where one or both feet are below the buttocks). Some medical opinions even advocated for C-section if the estimated fetal weight was 3500 grams or more. Furthermore, if significant danger to the mother or fetus arose during a trial of vaginal breech labor, requiring immediate delivery, procedures like an emergency C-section would be considered. However, the transition from labor to an emergency C-section inherently involves a time delay due to preparations like disinfection and anesthesia, making it potentially unsuitable in extremely urgent scenarios.

Legal Proceedings: From First Instance to the High Court

Mr. and Mrs. X1, the plaintiffs (appellants before the Supreme Court), initiated legal action. They argued that they had entered into a contract for obstetric services with B Hospital, which was initially operated by the State and whose rights and obligations were later succeeded by H Organization. Their core contention was that Dr. Y1, despite their repeated and forceful expressions of desire for a C-section due to the fetus being in breech presentation, failed to adequately explain the risks associated with vaginal breech delivery and the comparative risks and benefits of a C-section. This failure, they claimed, deprived them of their fundamental right to make a fully informed decision about the method of delivery. As a result, they lost the opportunity to choose a C-section, which they believed would have led to a different outcome, and their son A ultimately died. They sought damages from Dr. Y1 based on tort (medical malpractice) and from H Organization based on either breach of contract or tort (vicarious liability for Dr. Y1's actions).

The court of first instance (Saitama District Court, Kawagoe Branch) partially sided with Mr. and Mrs. X1. It found Dr. Y1 liable in tort and awarded the plaintiffs a sum of 1.65 million yen each (1.5 million for emotional distress and 150,000 for attorney's fees).

However, this decision was overturned on appeal. The Tokyo High Court reversed the first instance judgment and dismissed the plaintiffs' claims in their entirety. The High Court reasoned that Dr. Y1 had determined, based on his clinical assessment of Mrs. X2 and the fetus, that vaginal delivery was not only possible but also appropriate. While acknowledging that Dr. Y1's explanations might have leaned towards emphasizing the merits of vaginal delivery, the High Court found that he had included information about the potential risks of vaginal delivery and how they might be managed. The High Court also took into account that Mrs. X2 already possessed some general knowledge regarding breech births. It concluded that Dr. Y1's explanations were "reasonable and sufficient" under the circumstances. Therefore, the High Court held that Dr. Y1 had fulfilled his required duty of explanation. It further stated that even if Mr. and Mrs. X1 had harbored a desire for a C-section but were persuaded by Dr. Y1 to opt for vaginal delivery, their right to make a free and autonomous decision had not been infringed.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision (September 8, 2005)

Dissatisfied with the High Court's ruling, Mr. and Mrs. X1 appealed to the Supreme Court of Japan. The Supreme Court overturned the Tokyo High Court's judgment and remanded the case back to the High Court for further proceedings, effectively finding in favor of the parents' arguments regarding the inadequacy of the informed consent process.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was detailed and critical of Dr. Y1's conduct:

1. The Parents' Request for a Cesarean Section Was Medically Reasonable:

The Court began by acknowledging the undisputed facts: Mr. and Mrs. X1, driven by anxiety over a vaginal breech delivery, had repeatedly and emphatically communicated their strong desire for a C-section. The Supreme Court stated that, considering existing medical knowledge and practices at the time—for instance, the view that a C-section might be indicated for an estimated fetal weight of 3500 grams or more in breech cases—the parents' request for a C-section "had a reasonable basis from a medical perspective." The Court noted that the ultrasound estimation of fetal weight (3057g on April 27) had a margin of error of 10-15%, and the fetus could gain approximately 200g more in the two weeks leading up to the actual delivery (which occurred even later, past the due date). This meant it was foreseeable that the birth weight could exceed 3500g.

2. Dr. Y1's Deficient Explanation and Breach of Duty of Care:

The Supreme Court found Dr. Y1's explanations and actions fell short of the required standard of care in several key aspects:

- Duty to Provide Specific, Updated, and Comprehensive Information: Dr. Y1 had a duty to provide Mr. and Mrs. X1 with the most current possible information relevant to their decision. This included:

- Latest Estimated Fetal Weight: He should have attempted to get a more recent estimate of fetal weight, especially since Mrs. X2 expressed concerns about the baby's size after her due date had passed. His response that "the baby doesn't grow much after the due date" was insufficient, particularly given that he hadn't re-measured since April 27.

- Fetal Position (Presentation): He should have informed them of any changes or specific details about the fetal presentation. Crucially, when he diagnosed the compound breech presentation on the morning of May 12, he failed to communicate this significant finding to the parents before proceeding with labor augmentation and the eventual artificial rupture of membranes.

- Other Critical Factors: He needed to explain other elements crucial for selecting the delivery method in a breech case.

- Concrete Rationale for Vaginal Delivery: Dr. Y1 was obligated to specifically and concretely explain his reasons for deeming vaginal delivery appropriate, grounded in these latest, specific fetal assessments.

- Duty to Explain the Realities of Transitioning to an Emergency C-Section: Dr. Y1 had a duty to clearly inform the parents that switching from a vaginal delivery attempt to an emergency C-section requires a certain amount of time for preparation (anesthesia, surgical setup, etc.). He should have also explained that urgent situations could arise where such a transition might not be a clinically appropriate or timely lifesaving option. His blanket reassurances did not convey these critical limitations.

- Misleading Reassurances: The Court found Dr. Y1's statements to be problematic. For example, when Mrs. X2 voiced her concern about the baby's size post-due date, his reply was dismissive. More seriously, his assertions like, "if anything happens during delivery, we can switch to a C-section immediately, so there is nothing to worry about," were deemed "extremely definitive." The Supreme Court concluded that such statements gave the parents a misleading impression regarding the ease, speed, and universal applicability of transitioning to a C-section should an emergency arise during vaginal delivery.

- Insufficient Overall Explanation: While Dr. Y1 had provided some general information about the risks of vaginal delivery, the Supreme Court found that he had failed to adequately explain his reasons for choosing vaginal delivery based on the latest, specific condition of the fetus. Coupled with his misleading statements about the immediate availability and feasibility of an emergency C-section, his overall explanation was insufficient.

3. Consequence of the Deficient Explanation – Deprivation of Informed Choice:

The Supreme Court highlighted that Mr. and Mrs. X1 maintained a strong desire for a C-section throughout. However, they ultimately acquiesced to a trial of vaginal delivery under Dr. Y1's care because his explanations led them to believe that if any problems occurred, an immediate C-section would be performed, ensuring the baby's safe delivery. They were not given the opportunity to:

* Recognize the latest condition of the fetus (e.g., the uncommunicated compound breech presentation, the potential for a larger fetal weight).

* Concretely understand the true risks associated with vaginal delivery in their specific, evolving circumstances.

* Make a genuinely informed decision about whether to accept vaginal delivery under Dr. Y1's management.

Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that Dr. Y1's explanations did not fulfill the duty of care owed to his patients. The High Court's judgment, which found the explanations sufficient, was deemed to contain errors in the application of the law that clearly affected its outcome. The case was thus remanded for further deliberation by the High Court, consistent with the Supreme Court's findings.

Understanding Informed Consent and Patient Autonomy in Light of the Ruling

This Supreme Court decision powerfully reaffirms fundamental principles of medical ethics and law, particularly the doctrine of informed consent and the right to patient autonomy.

The Core Principle of Self-Determination: At its heart, informed consent is rooted in the concept that every individual has the right to make decisions about their own body and what medical treatments they will or will not undergo. For consent to be truly "informed," it cannot be a mere formality or a signature on a form. It requires a genuine understanding by the patient.

The Physician's Duty of Explanation: A physician's duty to explain is not merely a passive provision of facts but an active process of communication designed to empower the patient. This duty involves conveying information about:

- The nature of the patient's condition (diagnosis).

- The proposed treatment: its purpose, procedures involved, and expected benefits.

- The material risks associated with the proposed treatment: potential complications, side effects, and their likelihood and severity.

- Alternative treatments or courses of action: including the option of no treatment, along with their respective benefits and risks.

- The prognosis: the likely outcome with and without the proposed treatment or alternatives.

Qualities of Adequate Information: For an explanation to be adequate, the information provided must be:

- Accurate and Up-to-Date: As this case illustrates, relying on outdated information (like the fetal weight estimate from weeks prior) or failing to communicate new diagnostic findings (the compound breech presentation) is a critical lapse. Medical situations, especially in obstetrics, can be dynamic.

- Specific to the Patient: General information about a condition or procedure is a starting point, but the explanation must be tailored to the individual patient's unique clinical circumstances.

- Comprehensive: It should cover the necessary elements—risks, benefits, alternatives—to enable a balanced consideration.

- Understandable: Physicians should strive to communicate in clear language, avoiding overly technical jargon where possible, or explaining it carefully. Conversely, as seen in this case, overly simplistic or sweepingly reassuring statements that obscure genuine risks can be just as problematic as non-disclosure.

The Significance of Patient Preference and Concerns: This case underscores that when a patient expresses clear preferences for a particular medically recognized treatment option (like Mr. and Mrs. X1's consistent requests for a C-section, which the Supreme Court deemed medically reasonable to consider), those preferences must be taken seriously. The physician has a heightened duty to thoroughly address the patient's concerns and explain why a different course might be recommended, ensuring the patient understands the rationale. Dismissing patient anxieties can undermine the informed consent process.

The Peril of Misleading Information: Dr. Y1’s definitive reassurances about the immediate availability and universal applicability of an emergency C-section were a key factor in the Supreme Court's decision. Such statements can create a false sense of security, preventing patients from accurately weighing the risks of the recommended course of action. Misleading information can vitiate consent as effectively as a complete failure to disclose.

Loss of Opportunity and the Nature of Harm: In cases of deficient informed consent, the harm suffered by the patient is not always contingent on proving that the alternative treatment would definitively have produced a better physical outcome. Instead, a significant aspect of the harm is the violation of the patient's right to self-determination—the deprivation of their right to choose. Had Mr. and Mrs. X1 been fully and accurately informed of the evolving risks, the uncommunicated compound breech presentation, the realistic limitations of emergency C-sections, and the uncertainty surrounding the fetal weight, they might have insisted more effectively on a C-section, or sought care elsewhere if their primary wish was not accommodated. The loss of this opportunity to exercise their autonomy and make a choice based on complete and truthful information is, in itself, a cognizable injury.

This ruling emphasizes that the physician's duty of explanation becomes particularly acute when:

- The patient explicitly voices preferences for a medically viable alternative treatment.

- The clinical situation is dynamic and evolving, requiring updates to previously discussed plans.

- The recommended course of action carries inherent and significant risks, which must be conveyed without being downplayed by misleading assurances.

Conclusion

The September 8, 2005, decision by the Supreme Court of Japan stands as a crucial reminder of the profound legal and ethical responsibilities incumbent upon medical professionals in the realm of informed consent. It highlights that the standard for medical explanations is high, especially when patients are faced with choices between different established treatment modalities, each with its own set of risks and benefits.

The ruling underscores that a physician's duty extends beyond merely listing facts; it involves fostering genuine understanding, honestly addressing patient concerns, and empowering patients to make autonomous choices based on accurate, up-to-date, and non-misleading information. The tragic circumstances of this case, and the Court's meticulous analysis of the communication failures, serve as a powerful testament to the importance of transparent and respectful dialogue in the patient-doctor relationship and the devastating consequences that can arise when this fundamental aspect of care is compromised.