A Quake, A Fire, and a Question of Insurance: Japan's Supreme Court on Solatium for Flawed Financial Advice

Judgment Date: December 9, 2003

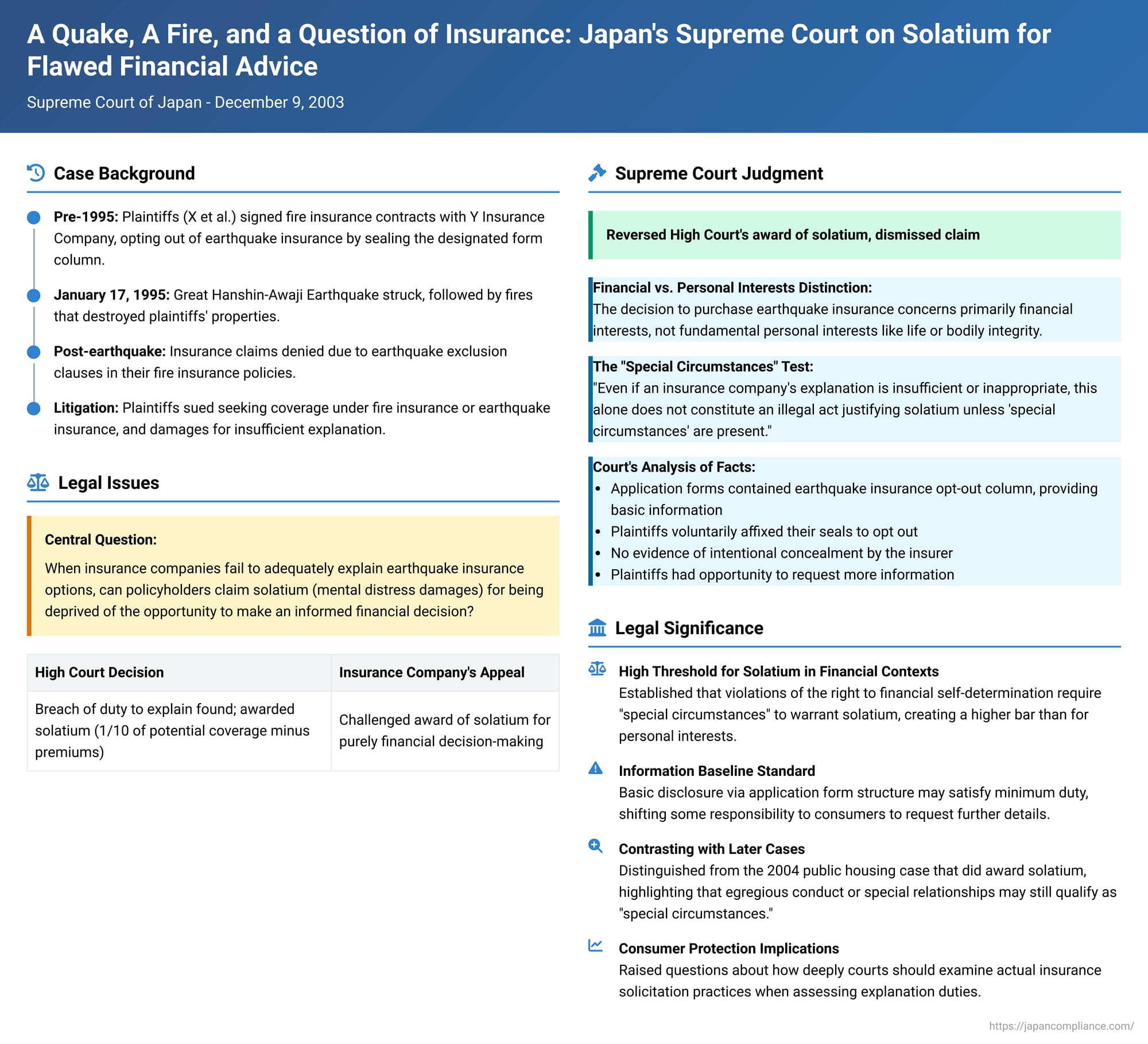

In the aftermath of the devastating Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake of 1995, numerous legal battles ensued over insurance coverage. One such case, culminating in a Supreme Court judgment on December 9, 2003 (Heisei 14 (Ju) No. 218), addressed a critical question: if an insurance company fails to adequately explain options regarding earthquake insurance when policyholders are signing up for fire insurance, can those policyholders later claim "solatium" (慰謝料 - isharyō, damages for mental distress or loss of self-determination) for having been deprived of the opportunity to make a fully informed financial decision? This ruling delved into the insurer's duty to provide information and the threshold for awarding non-pecuniary damages in the context of financial product choices.

The Tragic Backdrop: Earthquake, Subsequent Fires, and Gaps in Coverage

The plaintiffs, X et al., were individuals who owned or occupied buildings and household goods in Kobe City. They had all entered into fire insurance contracts with the defendant, Y Insurance Company. These standard fire insurance policies contained "earthquake exclusion clauses" (地震免責条項 - jishin menseki jōkō). These clauses stipulated that the insurer would not pay for damages caused by earthquakes, including damages from fires that were triggered by or spread due to an earthquake.

On January 17, 1995, the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake struck. Later that day, a fire originating from the premises of a Company A spread, ultimately engulfing and destroying the properties insured by X et al. Because this fire damage was directly linked to the earthquake (either as an earthquake-caused fire that spread or a fire whose spread was exacerbated by the earthquake), it fell under the earthquake exclusion clause of their fire insurance policies, meaning their primary fire insurance would not cover the loss.

In Japan, coverage for earthquake-related risks, including earthquake-induced fires, is provided through a separate earthquake insurance system established under the "Act on Earthquake Insurance" (地震保険に関する法律 - Jishin Hoken ni Kansuru Hōritsu). This earthquake insurance is not typically sold as a standalone policy but is designed to be attached to a primary non-life insurance contract, such as a fire insurance policy. A key feature of this system is the "principle of automatic attachment" (原則的自動附帯 - gensokuteki jidō futai): insurance companies are generally required to offer and underwrite earthquake insurance as an add-on to fire insurance policies unless the policyholder explicitly states their intention not to purchase it. To facilitate this, fire insurance application forms commonly include an "earthquake insurance non-joinder intention confirmation column" (地震保険不加入意思確認欄 - jishin hoken fukanyū ishi kakunin ran). This section usually contains a statement like, "I do not apply for earthquake insurance" (「地震保険は申し込みません」), and applicants who wish to decline earthquake coverage are required to affix their personal seal (hanko) in this designated space.

The Policyholders' Claims: Seeking Coverage and Compensation

Having suffered catastrophic losses not covered by their standard fire insurance, X et al. pursued several legal claims against Y Insurance Company:

- Primary Claim: Payment under their existing fire insurance contracts, arguing the fire was a separate event.

- Alternative Claim 1 (Implicit Contract): Payment under earthquake insurance policies, asserting that such policies should be deemed to have been concluded because they had not made a legally effective declaration to opt out.

- Alternative Claim 2 (Damages for Breach of Duty - Key Focus): Compensation for Y Insurance Company's alleged failure in its duty to provide adequate information and explanation regarding earthquake insurance when X et al. were initially signing their fire insurance contracts. This claim was multifaceted, invoking:

- Violations of the (now repealed) Act on Control of Insurance Solicitation (募取法 - Boshuhō).

- Tort liability.

- Breach of contract (non-performance of an ancillary duty).

- Culpa in contrahendo (fault in the contracting process).

Under this claim, X et al. first sought financial damages, equivalent to either the full fire insurance payout or the earthquake insurance payout less the premiums they would have paid. Secondarily, and crucially for this Supreme Court decision, they sought solatium for mental distress, also benchmarked against the potential earthquake insurance payout less premiums, arguing they were deprived of the chance to make an informed decision about this vital coverage.

The Lower Court's Finding: Breach of Duty and Award of Solatium

The Osaka High Court, as the lower appellate court, found that Y Insurance Company had indeed breached a duty of explanation. It reasoned that insurance companies have a good faith obligation to inform applicants about important matters related to earthquake insurance, given the significant information asymmetry between insurers and policyholders. The High Court considered that if Y had fulfilled this duty, X et al. might well have chosen to take up earthquake insurance. Consequently, it recognized that X et al. had lost the "opportunity for self-determination" regarding this coverage. While rejecting the claims for direct financial damages under this head, the High Court awarded X et al. solatium equivalent to one-tenth of the difference between the potential earthquake insurance payout and the premiums that would have been due. Y Insurance Company appealed this award of solatium to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Reversal: A High Bar for Solatium in Financial Decisions

The Supreme Court reversed the Osaka High Court's judgment regarding the award of solatium, ultimately dismissing this part of X et al.'s claim.

The Court's central reasoning revolved around the nature of the decision involved:

- Financial vs. Personal Interests: The decision of whether or not to purchase earthquake insurance is primarily a decision concerning financial interests—the protection of property against financial loss. It does not directly pertain to fundamental personal interests such as life, bodily integrity, or liberty, where violations of the right to self-determination have more readily led to awards of solatium (e.g., in medical malpractice cases involving informed consent).

- The "Special Circumstances" Test: Given this financial nature, the Supreme Court established that even if an insurance company's provision of information or explanation was "in some way insufficient or inappropriate," this would not, in itself, constitute an "illegal act" (違法行為 - ihō kōi) justifying an award of solatium, unless "special circumstances" (特段の事情 - tokudan no jijō) were present. These special circumstances would need to elevate the insurer's conduct to a level of wrongfulness beyond mere insufficiency.

Applying this test to the facts of the case, the Supreme Court found no such "special circumstances":

- Information Provided by the Application Form: The Court emphasized that the fire insurance application forms used by X et al. contained the "earthquake insurance non-joinder intention confirmation column." The presence of this column, with its explicit statement "I do not apply for earthquake insurance," was deemed to provide applicants with several key pieces of information:

- That earthquake insurance exists as a separate coverage from standard fire insurance.

- That these two types of insurance are distinct, and being enrolled in fire insurance does not automatically mean one is covered for earthquake-related perils.

- That affixing one's seal in this specific column signifies a decision not to take up earthquake insurance.

The Supreme Court viewed this as a baseline level of information. Based on this, it concluded that X et al. had a "sufficient opportunity" to request more detailed information from Y Insurance Company if they desired it—such as the precise scope of coverage for both types of insurance, the details of the earthquake exclusion clause, and the premium costs for earthquake insurance.

- Policyholders' Actions: The Court noted that all plaintiffs (X et al.) had, in fact, affixed their personal seals to this opt-out column, and did so "based on their own volition." This act, in the Court's view, suggested that X et al. understood the basic information conveyed by the form and the implications of sealing the declination box.

- No Intentional Concealment by the Insurer: The Court found no evidence that Y Insurance Company had intentionally concealed information about earthquake insurance from X et al. during the contracting process.

Considering these points, the Supreme Court held that even if there were some "insufficient points" in Y Insurance Company's information provision or explanation regarding earthquake insurance, the "special circumstances" required to classify this as an illegal act warranting solatium did not exist.

Analyzing the "Duty to Explain" and the "Special Circumstances" Threshold

The Supreme Court's decision in this case sets a relatively high bar for claiming solatium arising from an alleged breach of an insurer's duty to explain when the underlying decision is primarily financial. The judgment suggests that the mere existence of an information gap or a less-than-perfect explanation by the insurer may not be enough.

The Court placed significant weight on the information conveyed by the structure of the application form itself. The explicit opt-out mechanism for earthquake insurance was seen as providing policyholders with a fundamental awareness of their options and a clear opportunity to seek further clarification. This implies that, in the absence of more egregious conduct by the insurer (like active misrepresentation or deliberate, intentional concealment of critical information), the onus might shift somewhat to the consumer to ask for more details if the basic choice is presented.

This ruling has been contrasted with a later Supreme Court decision (issued on November 18, 2004, concerning a public corporation's sale of housing where it failed to disclose an intent to later lower prices ), which did award solatium for the infringement of a financial decision-making opportunity and explicitly stated it did not conflict with this 2003 earthquake insurance judgment. The distinguishing factor appears to be the perceived severity and nature of the information provider's conduct. In the 2004 housing case, there was a failure to disclose crucial information that the provider knew was contrary to the buyer's understanding, an understanding fostered by prior specific agreements, which was deemed a "significant violation of the principle of good faith and fair dealing" constituting the "special circumstances" absent in the earthquake insurance case. In the earthquake insurance case, the perceived inadequacy was more passive and did not involve overriding a pre-existing special relationship or expectation in the same way.

Some legal commentators have pointed out that the Supreme Court, in this 2003 earthquake insurance decision, did not deeply investigate the actual practices of insurance agents at the time, such as whether the earthquake insurance opt-out was routinely checked by agents without full engagement from the applicants. Given the relatively low uptake of earthquake insurance in Hyogo Prefecture (around 3%) before the 1995 disaster, a more searching inquiry into the practical realities of the solicitation process might have been warranted from a consumer protection standpoint.

Broader Implications: Solatium for Infringed Financial Self-Determination

This case is a key reference point in the evolving jurisprudence on solatium for the infringement of the right to self-determination, particularly when financial interests are primarily at stake. While Japanese courts have recognized such claims in contexts involving fundamental personal interests (e.g., informed consent in medical treatments), this decision signaled a more cautious approach for purely financial choices.

It does not entirely preclude solatium for flawed financial advice or information failures but indicates that the threshold for "illegality" is higher. The insurer's conduct must generally involve more than simple inadequacy in explanation; it likely needs to reach a level of bad faith, deliberate concealment, or other aggravating factors that constitute "special circumstances" to justify compensation for mental distress or the loss of an informed choice. The concept of "loss of an opportunity to make an informed decision" is acknowledged as a potential harm, but its compensability as non-pecuniary damage in financial transactions is carefully circumscribed.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's December 9, 2003, judgment clarified that while insurers have a duty to provide information, an insufficient explanation regarding earthquake insurance—a decision pertaining to financial interests—does not automatically give rise to a claim for solatium for the policyholder. In the absence of "special circumstances" indicating a more severe degree of misconduct by the insurer, such as intentional concealment, the Court found that the information and choices presented on the standard application form provided a baseline opportunity for policyholders to make their decision or seek further details. This ruling emphasizes the distinction drawn in Japanese law between the protection of personal and financial interests when considering claims for non-pecuniary damages arising from failures in information provision.