A Photo Finish in Claim Assignments: How Japan's Supreme Court Resolves Priority When Notice Timings are Unknown

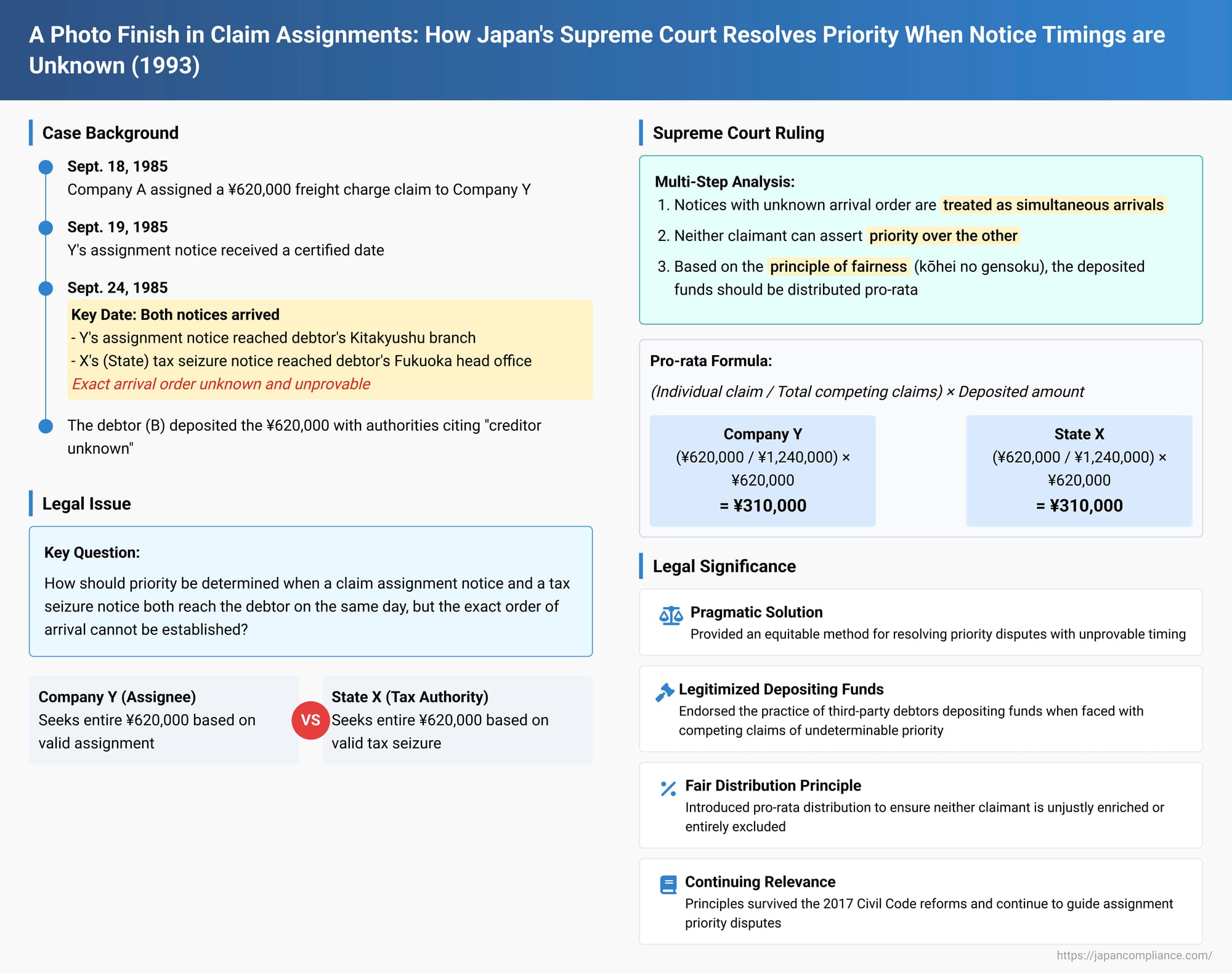

In the world of commercial law, the assignment (sale or transfer) of monetary claims is a daily occurrence. A critical aspect of this process is "perfection"—the steps an assignee must take to make their newly acquired right effective against the original debtor of the claim and, crucially, against other third parties who might also have an interest in that same claim. Japanese law has long stipulated that perfection against third parties typically involves notifying the debtor of the assignment using a document with a "certified date" (kakutei hizuke). But what happens when, for instance, an assignee sends such a notice, and a creditor of the original assignor (like a tax authority) also seizes the same claim, and both notices reach the debtor on the same day, but no one can prove which arrived first? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this "photo finish" scenario in a significant judgment on March 30, 1993 (Showa 63 (O) No. 1526).

Recap: Perfecting Claim Assignments in Japan – The "Arrival Time" Rule

To understand the 1993 case, it's helpful to recall a principle clarified by earlier Supreme Court decisions (such as the judgment of March 7, 1974). Generally, when multiple parties claim rights to the same assigned debt, their priority is determined by the actual time of arrival of their respective notices (which must bear a certified date) to the third-party debtor who owes the money. The earlier the perfected notice arrives, the stronger the claim against other third parties. A certified date, often from a notary or content-certified mail, serves to prevent fraudulent backdating of the notice.

The Challenge: What if Arrival Times are Genuinely Unknown?

The 1974 ruling addressed situations where arrival times could be proven. The 1993 case tackled the more perplexing scenario: what if it's undisputed that both notices arrived on the same calendar day, but the precise sequence—which one was minutes or hours ahead of the other—is unknown and cannot be established?

Facts of the 1993 Case: Assignment vs. Tax Seizure – A Dead Heat?

The case involved the following parties and events:

- A: A transport company that was owed money.

- B: A transport business cooperative association that owed A a freight charge claim of 620,000 yen (the "Claim").

- Y: A company that was assigned the entire Claim by A on September 18, 1985. A (the assignor) notified B (the third-party debtor) of this assignment via content-certified mail. This notice bore a certified date of September 19, 1985, and it reached B's Kitakyushu branch office on September 24, 1985.

- X: The State (specifically, the Fukuoka Regional Tax Bureau, Kashii Tax Office), which had a tax claim of over 2.44 million yen against A. On September 24, 1985, X seized the entire 620,000 yen Claim owed by B to A to collect on A's unpaid taxes. The notice of this tax seizure was served on B's Fukuoka head office on the same day, September 24, 1985.

The Crucial Impasse: Despite both X's tax seizure notice and Y's assignment notice reaching B (the third-party debtor) on the same calendar day (September 24, 1985), the precise order of their arrival was unknown and could not be proven.

Faced with this uncertainty, B deposited the 620,000 yen with the authorities, citing "creditor unknown." X (the State) then sued Y (the assignee), seeking confirmation of X's right to collect the entire deposited sum. Y, in turn, filed a counterclaim, also seeking confirmation of its right to the entire sum.

The lower appellate court had held that because the arrival order was unknown, the notices should be treated as having arrived simultaneously, meaning neither X nor Y could claim priority over the other. It thus dismissed both parties' claims to the entire fund.

The Supreme Court's Solution for "Arrival Order Unknown"

The Supreme Court provided a clear, multi-step resolution:

- Treat as Simultaneous Arrival: The Court affirmed that when a notice of tax seizure (under the National Tax Collection Act) and a notice of claim assignment (bearing a certified date) both reach the third-party debtor, but the precise order of their arrival is unknown and thus priority cannot be determined by sequence, these notices are to be treated as having arrived simultaneously. This aligns with principles from earlier case law dealing with known simultaneous arrivals.

- No Priority Over Each Other: In such a situation of deemed simultaneous arrival, neither the attaching creditor (X) nor the assignee (Y) can assert that they have a superior legal position or priority over the other concerning the claim. Both hold valid, perfected claims against the third-party debtor (B) for the amount specified in their respective actions. The Court cited a 1980 precedent stating that an assignee can still sue the third-party debtor and win, even if there's a competing tax seizure.

- Distribution of Deposited Funds – The Principle of Fairness (kōhei no gensoku): This was the most novel and significant part of the ruling. If the third-party debtor has deposited the funds due to uncertainty about the rightful creditor (arising from the unknown arrival order of competing notices), and if the sum of the amounts claimed by the competing parties (e.g., the amount of the tax seizure and the amount of the assigned claim) exceeds the total amount deposited, then the solution is not "winner takes all" or an impasse. Instead, the Supreme Court held that the attaching creditor (X) and the assignee (Y), based on the principle of fairness, should each acquire a right to a portion of the deposited funds. This portion is to be calculated pro-rata, according to the respective amounts of their valid claims being asserted against the specific deposited fund. In essence, they share the deposited amount in proportion to their claims.

- Outcome in the Case:

- X's tax seizure targeted the full 620,000 yen Claim.

- Y's assignment also covered the full 620,000 yen Claim.

- The sum of these claims (620,000 yen + 620,000 yen = 1,240,000 yen) exceeded the amount B had deposited (620,000 yen).

- Therefore, applying the pro-rata principle, X (the State) and Y (the assignee) were each entitled to:

(Their respective claim on the fund / Total of competing claims on the fund) * Deposited Amount

= (620,000 / 1,240,000) * 620,000 yen = 310,000 yen each.

The Supreme Court thus modified the lower court's judgment to confirm X's right to collect 310,000 yen from the deposit (and implicitly, Y would be entitled to the other 310,000 yen).

Significance and Implications of the Ruling

This 1993 Supreme Court decision provided crucial practical guidance:

- A Pragmatic Solution for Indeterminate Priority: It established a clear and equitable method for resolving priority disputes when the exact timing of competing perfection acts cannot be definitively proven. Instead of leaving the parties in an unbreakable deadlock or resorting to arbitrary rules, it opted for a fair sharing mechanism.

- Endorsement of Deposits in "Arrival Order Unknown" Cases: The ruling gave legitimacy to the practice of third-party debtors depositing funds when faced with competing claims whose arrival order is unknown. Post-judgment, Ministry of Justice circulars confirmed that such deposits citing "creditor unknown" would be accepted by deposit offices.

- Alignment with "Simultaneous Arrival" Principles: The decision logically extended the principles applied in cases of known simultaneous arrival (where neither claimant has priority over the other) to situations where the order of arrival is simply unprovable.

- Focus on Fairness in Distribution: The introduction of pro-rata distribution based on the principle of fairness ensures that when a limited fund is insufficient to satisfy all valid competing claims of equal (or indeterminable) priority, no single claimant is unjustly enriched or entirely excluded.

- Ongoing Debates on Underlying Rights: It's important to note that while this judgment provides a clear rule for the distribution of deposited funds, legal scholars continue to debate the precise underlying legal nature of the claimants' rights in such simultaneous/unknown arrival scenarios, especially if no deposit is made (e.g., are they co-owners of the claim, or do they hold some form of joint creditor-ship, and if one is paid in full by the debtor, must they share with the other?).

Continuing Relevance (Post-2017 Civil Code Reform)

The fundamental rules for perfecting claim assignments against third parties through notice to the debtor (as outlined in Article 467 of the Civil Code) were not drastically altered in the 2017 Civil Code reforms with respect to this specific priority determination mechanism (i.e., the importance of the arrival time of a certified notice/consent). While the reforms addressed many other aspects of claim assignments, the core principles governing how to resolve competing claims based on the timing of perfection against the third-party debtor remain largely guided by case law. Therefore, this 1993 Supreme Court judgment, with its practical approach to "arrival order unknown" scenarios, continues to be an important and influential piece of jurisprudence in Japan.

Conclusion

The 1993 Supreme Court decision offers a clear and equitable pathway for resolving difficult priority disputes that arise when multiple valid claims—such as a claim assignment and a tax seizure—are perfected against a third-party debtor on the same day, but the exact sequence of these perfections cannot be established. By treating such cases as instances of simultaneous arrival and mandating a pro-rata distribution of any funds deposited by the debtor, the Court provided essential guidance that promotes fairness and predictability in Japanese claim assignment law. It underscores that even in a "photo finish," the law strives for a balanced outcome.