A Nation Tuned In: The Japanese Supreme Court's Definitive Stance on NHK Reception Contracts

Judgment Date: December 6, 2017

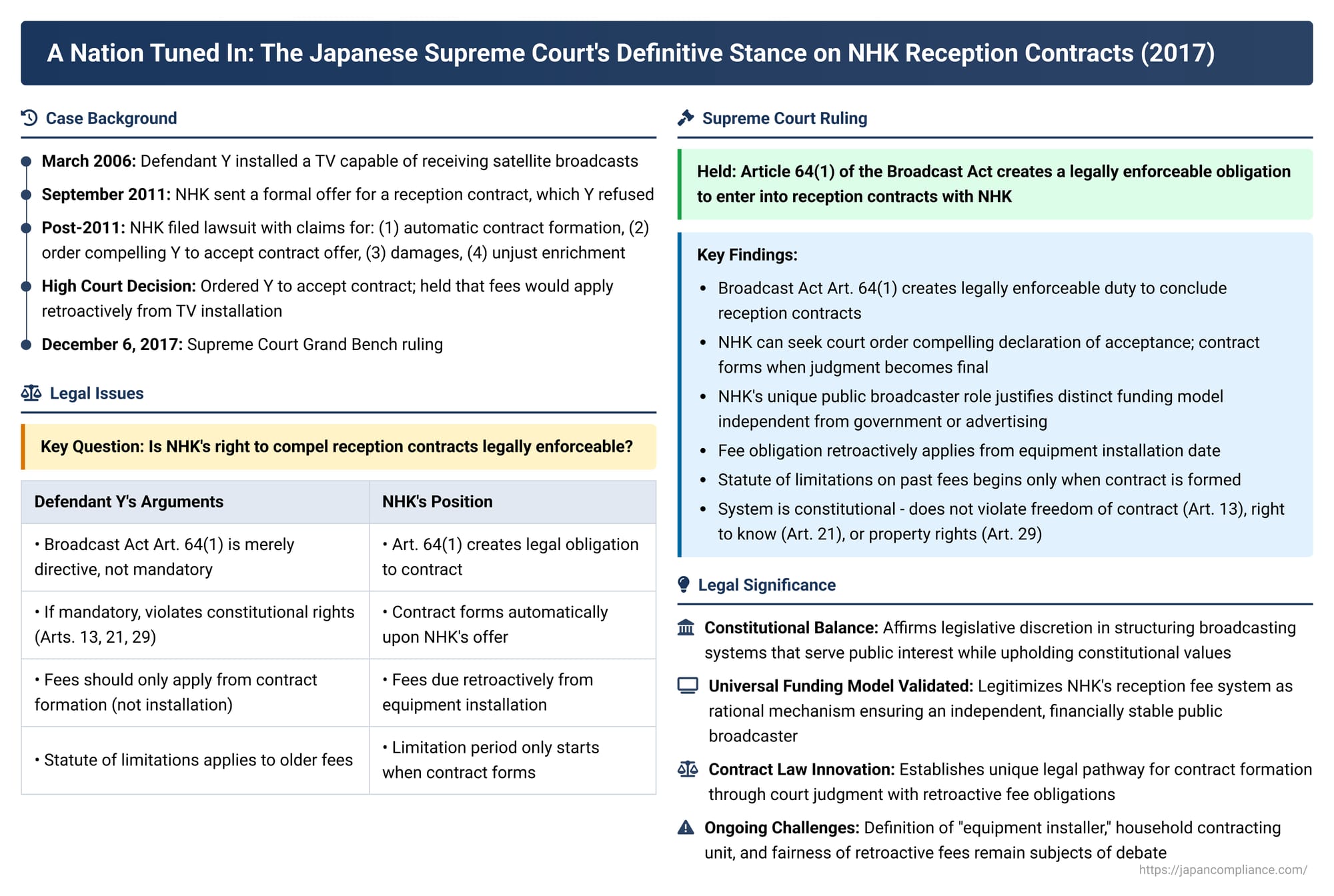

In a landmark decision with far-reaching implications for millions of television owners in Japan, the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court on December 6, 2017, ruled on the controversial issue of NHK (Nippon Hōsō Kyōkai - Japan Broadcasting Corporation) reception contracts. The case (Reception Contract Conclusion Acceptance, etc. Claim Case, Heisei 26 (O) No. 1130, Heisei 26 (Ju) No. 1440, No. 1441) addressed whether NHK, Japan's public broadcaster, can legally compel individuals who own television-receiving equipment to enter into and pay for broadcast reception contracts, and delved into the constitutional and practical dimensions of this obligation.

The Heart of the Dispute: An Unwilling Viewer and a Public Broadcaster's Mandate

The defendant, an individual identified as Y, had installed a color television capable of receiving NHK's satellite broadcasts in his residence on or after March 22, 2006. NHK (the plaintiff, referred to as X in the provided commentary but will be referred to as NHK here for clarity as the public broadcaster) sent a formal offer for a broadcast reception contract to Y, which was received on September 21, 2011. Y, however, did not consent to this offer.

NHK subsequently initiated legal proceedings. Its primary claim was that a reception contract was automatically established the moment its offer reached Y, based on Article 64, Paragraph 1 of the Broadcast Act. Under this claim, NHK sought payment of reception fees totaling ¥215,640 for the period from April 2006 (the month following Y's TV installation) to January 2014.

Alternatively, NHK presented several preliminary claims:

- Damages for Y's failure to fulfill the alleged obligation to conclude a contract.

- A request for a court order compelling Y to declare acceptance of NHK's contract offer, and subsequently, payment of the aforementioned fees upon the contract's formation.

- Restitution for unjust enrichment, arguing Y benefited from potential reception without paying.

Y contested NHK's claims on multiple grounds. He argued that Article 64, Paragraph 1 of the Broadcast Act is merely a directive (hortatory) and does not create a legally enforceable obligation to contract. If interpreted as compulsory, Y contended it would infringe upon fundamental rights, including freedom of contract, the right to know, and property rights, thereby violating Articles 13, 21, and 29 of the Constitution. Y also disputed the scope of any potential fee obligation and invoked the statute of limitations for a portion of the claimed fees.

The Tokyo High Court, acting as the lower appellate court, dismissed NHK's primary claim of automatic contract formation. However, it granted NHK's second preliminary claim, ordering Y to express acceptance of the reception contract. The High Court ruled that the contract would be established once this judgment became final and binding, and significantly, that the obligation to pay reception fees would commence from the month Y installed the television receiving equipment. Both NHK and Y appealed aspects of this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court Deciphers Article 64, Paragraph 1 of the Broadcast Act

The Supreme Court, in its Grand Bench decision, ultimately dismissed the appeals, thereby upholding the core tenets of the Tokyo High Court's judgment.

- The Nature and Purpose of Article 64(1):

The Court began by underscoring the societal importance of broadcasting, stating it serves to substantially fulfill the people's right to know (guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution, which protects freedom of expression) and contributes to the development of a sound democracy, thus needing wide dissemination. The Broadcast Act, the Court noted, aims to regulate broadcasting for the public welfare and ensure its healthy development.It highlighted Japan's dual broadcasting system, comprising NHK as the public broadcaster and private commercial broadcasters. NHK is specifically tasked with conducting broadcasting for the "public welfare" throughout Japan. Its financial sustenance through reception fees, rather than advertising or direct government funding for operations, is designed to insulate it from the influence of specific individuals, organizations, or state bodies, ensuring it remains a service supported broadly by all those equipped to receive its broadcasts.The Court traced the origins of Article 64(1) to the post-World War II reforms. Under the pre-1950 system, installation of radio (and later TV) receiving equipment required a government permit, which was contingent upon entering a "listening contract" with NHK's predecessor. The new Broadcast Act abolished this permit system. The introduction of Article 64(1), requiring those with reception equipment to contract with NHK, was therefore interpreted as a "legally effective means" to secure NHK's financial foundation, making it "difficult to view it as a provision without legal force". - Mechanism of Contract Formation:

While affirming the obligatory nature of Article 64(1), the Court rejected NHK's primary argument that a contract is formed merely upon NHK's offer reaching the equipment installer. The Act specifies a "contract," implying the need for mutual assent. NHK is expected to strive for voluntary contract conclusion by explaining its mission and operations.However, for individuals who refuse to contract voluntarily, the Court endorsed the High Court's approach: Article 64(1) establishes a legal duty to conclude a reception contract. If an installer does not accept NHK's offer, NHK is entitled to seek a court judgment ordering the installer to express acceptance. The contract is deemed legally formed when such a judgment becomes final and unappealable. This mechanism relies on provisions in the Civil Code (Art. 414(2), proviso) and the Civil Execution Act (Art. 174(1), formerly in the Code of Civil Procedure) where a judgment can substitute for a party's declaration of intent. - Content of the Mandated Contract:

The Court acknowledged that the Broadcast Act itself does not detail the contract's terms. Instead, these are set forth in NHK's Standard Terms of Broadcast Reception ("Hōsō Jushin Kiyaku"), which NHK formulates. However, this is not an unfettered power. The reception fee amounts are effectively determined by the National Diet's approval of NHK's annual budget. Furthermore, the Standard Terms themselves require approval from the Minister of Internal Affairs and Communications (after consultation with the Radio Regulatory Council). The Court found that this regulatory framework ensures the contract terms align with NHK's public service objectives and are fair and appropriate for fee collection among installers. The specific terms relevant to Y's case were deemed to be within the necessary scope for proper and equitable fee collection, consistent with NHK's statutory purpose.

Constitutional Validity Affirmed

Y argued vigorously that compelling a contract under Article 64(1) violated several constitutional rights: freedom of contract (Art. 13, as part of the right to pursuit of happiness), the right to know (which implies a right not to know or receive information, Art. 21), and property rights (Art. 29).

The Supreme Court dismissed these constitutional challenges:

- Legislative Discretion: The Court recognized that broadcasting utilizes finite public airwaves and is inherently subject to state regulation (e.g., licensing of broadcast stations). How best to structure a broadcasting system to serve the public interest and uphold constitutional values like freedom of expression and the people's right to know falls within the Diet's legislative discretion.

- Rationality of the NHK System: The dual system, with a public broadcaster (NHK) funded by reception fees from all who have the means to receive its broadcasts, was deemed a rational mechanism to ensure an independent, financially stable entity capable of fulfilling the people's right to know and supporting a healthy democracy. This rationale, the Court found, had not been eroded by changes in the broadcasting environment. Y's freedom to watch television is not absolute and must be considered within this established public welfare framework.

- Proportionality of Compulsion: The method of imposing the fee obligation—requiring a contract, and if refused, allowing NHK to seek a court order for acceptance—was also found to be a reasonable means to achieve a legitimate public end. NHK is expected to seek voluntary compliance first. The content of the compelled contract is not arbitrary but is subject to public oversight and limited to what is necessary for NHK's objectives.

Therefore, the Court concluded that Article 64, Paragraph 1 of the Broadcast Act, as a provision mandating the conclusion of a reception contract with content necessary for appropriate and fair fee collection for NHK's purposes, does not violate Articles 13, 21, or 29 of the Constitution.

When Do Fee Obligations Commence?

A critical issue was the starting point of the fee obligation. NHK's Standard Terms stipulate that a contract party must pay fees from the month the reception equipment is installed. Y argued that if a contract is only formed upon a court judgment, fees should only be due from that point onwards.

The Supreme Court sided with NHK and the High Court on this. It reasoned that reception fees are meant to be collected broadly and fairly from all those who have installed reception equipment. Allowing those who delay contracting (until compelled by a court) to escape liability for fees accrued since installation, while those who promptly contract pay from the outset, would be inequitable. Thus, the provision in NHK's Standard Terms making fees payable from the month of installation is "necessary and reasonable for ensuring fairness among equipment installers" and aligns with the Broadcast Act's objectives.

Consequently, when a reception contract is formed through the finalization of a court order compelling acceptance, the resulting contract legally obligates the payment of reception fees retroactively from the month the equipment was installed.

The Statute of Limitations: A Delayed Start

The parties also disputed the application of the statute of limitations to NHK's fee claims. It was established (citing a prior Supreme Court case) that reception fee claims, being periodic payments, are subject to a 5-year statute of limitations under Civil Code Article 169. The contention was when this 5-year period begins to run.

Under Civil Code Article 166, Paragraph 1, a statute of limitations begins when the right can be exercised. The Supreme Court reasoned that NHK cannot legally exercise its right to claim specific reception fees before a reception contract is actually concluded.

The Court acknowledged an apparent imbalance: if a person voluntarily contracts but falls into arrears, the statute of limitations might extinguish older fee obligations. However, for a person who refuses to contract, the clock doesn't start ticking on those past "uncontracted" periods until the contract is judicially formed. The Court justified this by stating it is generally difficult for NHK to promptly identify all equipment installers unless notified by the installers themselves. Since installers have a legal duty under Article 64(1) to conclude a contract, it is "unavoidable" that those who fail to do so do not benefit from the statute of limitations running on pre-contractual period fees.

Therefore, the Supreme Court held that for reception fees accruing from the month of equipment installation up to the point of contract formation (excluding those whose due dates fall after contract formation), the statute of limitations begins to run only from the moment the reception contract is established (i.e., when the judgment ordering acceptance becomes final and binding).

Broader Impact and Ongoing Debates

The Supreme Court's 2017 judgment significantly solidified NHK's legal authority to collect reception fees. It confirmed that owning equipment capable of receiving NHK broadcasts carries with it a legally enforceable obligation to enter into a reception contract and pay fees, retroactively to the time of installation, with the statute of limitations for such past fees commencing only upon formal contract establishment.

The decision underscores a balancing act between the public interest in a well-funded, independent public broadcaster fulfilling democratic functions and the protection of individual contractual and financial freedoms. While the Court found the current system constitutional and rational, the ruling did not quell all debate.

Supplementary opinions from some Justices in this very case, and ongoing scholarly discussion, highlight lingering complexities. For instance, the definition of "equipment installer" can be challenging in diverse living situations (e.g., rental accommodations with pre-installed TVs, or the status of mobile phones with "One-Seg" TV receiving capabilities, which have been subject to separate litigation). The concept of a "household" as the contracting unit, as stipulated in NHK's Standard Terms, also presents ambiguities when compelling contracts, especially given diverse family structures and living arrangements, making it difficult to pinpoint the exact individual obligated to contract within a household.

Furthermore, the fairness of making fees retroactively due from installation, especially when coupled with a statute of limitations that only begins upon a potentially much later contract formation, has been questioned by critics, who argue it could place a significant burden on individuals unaware of or disagreeing with the obligation for extended periods. The dissenting opinion in this case, for example, raised issues about whether the content of NHK's Standard Terms, designed primarily for voluntary agreements, is truly suitable for a contract imposed by court order, particularly concerning the retroactive establishment of obligations and the identification of the contracting party. Such critiques suggest that while the Supreme Court has provided a clear legal pathway for NHK, the practical and philosophical debates surrounding the TV license system in Japan are likely to persist.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's December 2017 ruling decisively affirmed NHK's right to compel broadcast reception contracts and collect fees from individuals possessing TV-reception equipment. By validating the constitutionality of Article 64, Paragraph 1 of the Broadcast Act and clarifying the mechanisms for contract enforcement, fee accrual, and the application of the statute of limitations, the Court provided a strong legal underpinning for NHK's unique funding model, deemed essential for its role in Japanese society.