A Mistake, a Kick, and a Fatal Fall: Japan's Leading Case on Putative Excessive Self-Defense

Decision Date: March 26, 1987

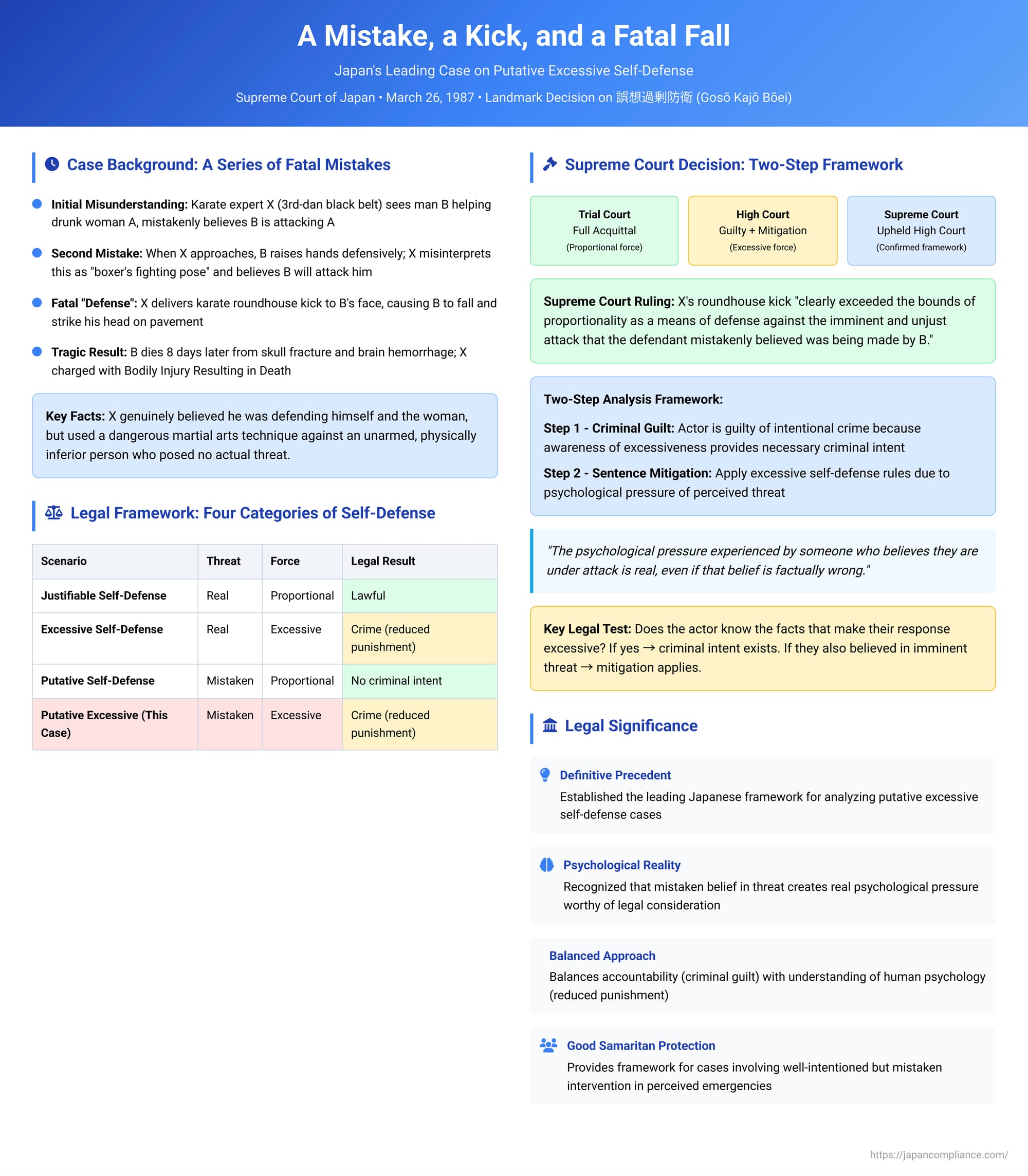

The law of self-defense is designed to justify the actions of a person repelling a genuine threat. But what happens when the situation is clouded by error? Legal systems have long grappled with two common types of mistakes: "putative self-defense," where a person mistakenly believes they are under attack and uses proportional force, and "excessive self-defense," where a person facing a real attack uses a disproportionate amount of force.

But what about the most complex scenario of all—a combination of both errors? What is the legal outcome when a person mistakenly believes they are under attack and uses force that would have been excessive even if that attack had been real? This is the thorny legal problem known as "putative excessive self-defense" (gosō kajō bōei). On March 26, 1987, the Supreme Court of Japan issued its definitive ruling on the issue, establishing a crucial two-part framework for analyzing these compounded errors of judgment.

The Factual Background: A Good Samaritan's Fatal Mistake

The case began with a well-intentioned but disastrous misunderstanding on a public street at night. The defendant, X, a man with a 3rd-dan black belt in karate, witnessed what he perceived to be an assault. He saw a man, B, struggling with a drunk woman, A. In reality, B was merely trying to calm A down and assist her.

The First Mistake: Misinterpreting the Situation

X misinterpreted the scene entirely, believing that B was attacking A. He decided to intervene to protect the woman. He stepped between the two.

The Second Mistake: Misinterpreting the Reaction

As X approached B with his hands outstretched, B, seeing a stranger advance on him, defensively raised his hands into a posture that X described as being "like a boxer's fighting pose." X made his second critical error, believing that B was now about to attack him.

The "Defensive" Act

Convinced that both he and the woman A were in imminent danger, X reacted instantly. He lashed out with a karate roundhouse kick aimed at B's face. The kick connected with the right side of B's face, causing him to fall to the pavement and strike his head.

The Tragic Result

B suffered a severe skull fracture and other injuries from the fall. He died eight days later from a cerebral subdural hemorrhage and contusion caused by the head injury. X was charged with the crime of Bodily Injury Resulting in Death.

The Journey Through the Courts: Navigating a Legal Minefield

The complexity of the case was reflected in the diverging opinions of the lower courts as they tried to apply the law to this series of mistakes.

- The Trial Court: A Full Acquittal. The first-instance court found that X genuinely, though mistakenly, believed he was under an imminent threat from B. Crucially, the trial judge also found that the roundhouse kick would have been a proportionate means of defense against the attack that X imagined. Because X's mistake about the threat was found to be non-negligent, the court concluded he lacked criminal intent and acquitted him completely.

- The High Court: A Finding of Excessiveness. The prosecutor appealed. The Tokyo High Court agreed with the trial court on one point: X did mistakenly believe he was under attack. However, it strongly disagreed on the issue of proportionality. The High Court found that a roundhouse kick, a dangerous martial arts technique delivered by a skilled practitioner, was an excessive and disproportionate response to the imagined threat from B, who was unarmed and physically inferior.

Having found that the act was both putative (based on a mistake) and excessive (disproportionate), the High Court articulated the key legal ruling. It held that in such a case, the defendant is not entitled to a full acquittal. It found X guilty of Bodily Injury Resulting in Death but then, "in accordance with" Article 36, Paragraph 2 of the Penal Code (the provision for excessive self-defense), it reduced his sentence to a suspended prison term.

The Supreme Court's Definitive Ruling

The defendant appealed, but the Supreme Court upheld the High Court's decision, cementing its reasoning as the law of the land for cases of putative excessive self-defense.

The Court affirmed the factual finding that X's roundhouse kick "clearly exceeded the bounds of proportionality as a means of defense against the imminent and unjust attack that the defendant mistakenly believed was being made by B."

Based on this, it held that the High Court's legal conclusion was "proper": the defendant was guilty of the underlying crime (in this case, Bodily Injury Resulting in Death), but his sentence could be mitigated by applying the rule for excessive self-defense.

A Deeper Dive: Unpacking the Theory of "Gosō Kajō Bōei"

This case requires navigating a complex legal taxonomy. To understand the Supreme Court's logic, it is helpful to distinguish the four key scenarios:

- Justifiable Self-Defense: A real threat is met with proportional force. The act is lawful.

- Excessive Self-Defense: A real threat is met with excessive force. The act is a crime, but punishment may be reduced or waived.

- Putative Self-Defense: A mistaken belief in a threat is met with what would have been proportional force. The actor lacks criminal intent and is not guilty of an intentional crime (though may be liable for negligence if the mistake was careless).

- Putative Excessive Self-Defense (This Case): A mistaken belief in a threat is met with excessive force.

The Supreme Court's 1987 decision provides a two-step framework for analyzing this fourth, most complex category.

Step 1: Why is the actor guilty of an intentional crime?

The core of this question lies in the actor's mens rea, or criminal intent. Under the prevailing view in Japanese law, a person who believes their actions are legally justified (as in simple putative self-defense) lacks the "intent to commit a crime."

However, the element of excessiveness changes the equation. In this case, the High Court found that X, as a skilled martial artist, was aware of the dangerousness of his technique and that less dangerous options were available. Because he was aware of the very facts that made his action excessive, he could not claim to have a fully clear conscience. His intent was not to act justifiably, but to use a level of force he knew to be highly dangerous and disproportionate. This awareness of the "facts constituting excessiveness" is what allows the court to find that he possessed the necessary criminal intent for the offense of causing injury.

Step 2: Why is the punishment reduced?

If the actor is guilty of an intentional crime, why should they get the benefit of a potential sentence reduction under the excessive self-defense rule? That rule, after all, is written for people facing a real attack.

The answer lies in the theoretical basis for the rule itself. The legal concession for excessive self-defense is largely understood to stem from the reduced culpability of a person acting under extreme psychological pressure. When a person believes they are facing an imminent, unlawful attack, their ability to make calm, rational judgments is compromised. They are in a state of fear, excitement, or confusion.

The Supreme Court's decision to allow the application of this rule to a mistaken defender implicitly endorses this "culpability reduction" theory. The Court recognized that the psychological pressure experienced by someone who believes they are under attack is real, even if that belief is factually wrong. It is this state of subjective turmoil—this mistaken belief that one is fighting for their safety—that reduces the actor's blameworthiness and justifies a potential mitigation of their punishment.

Conclusion: A Framework for Compounded Errors

The 1987 Supreme Court decision stands as a masterful piece of legal reasoning, providing a clear and logical framework for the confusing scenario of putative excessive self-defense. It establishes a two-step analysis that balances accountability with an understanding of human psychology:

- Guilt: The actor is found guilty of an intentional crime, because their awareness of the excessiveness of their own actions provides the necessary criminal intent.

- Mitigation: The court is then permitted to reduce or waive the punishment, applying the rule for excessive self-defense in recognition of the reduced culpability of an actor who, however mistakenly, believed they were in peril.

This ruling provides a humane and practical path through one of the most intellectually challenging corners of criminal law, ensuring that while individuals are held responsible for using disproportionate force, the law also acknowledges the powerful influence of a perceived, even if phantom, threat.