A Marriage of Convenience? Japan's Supreme Court on Intent and Validity When Legitimacy is the Goal

Date of Judgment: October 31, 1969

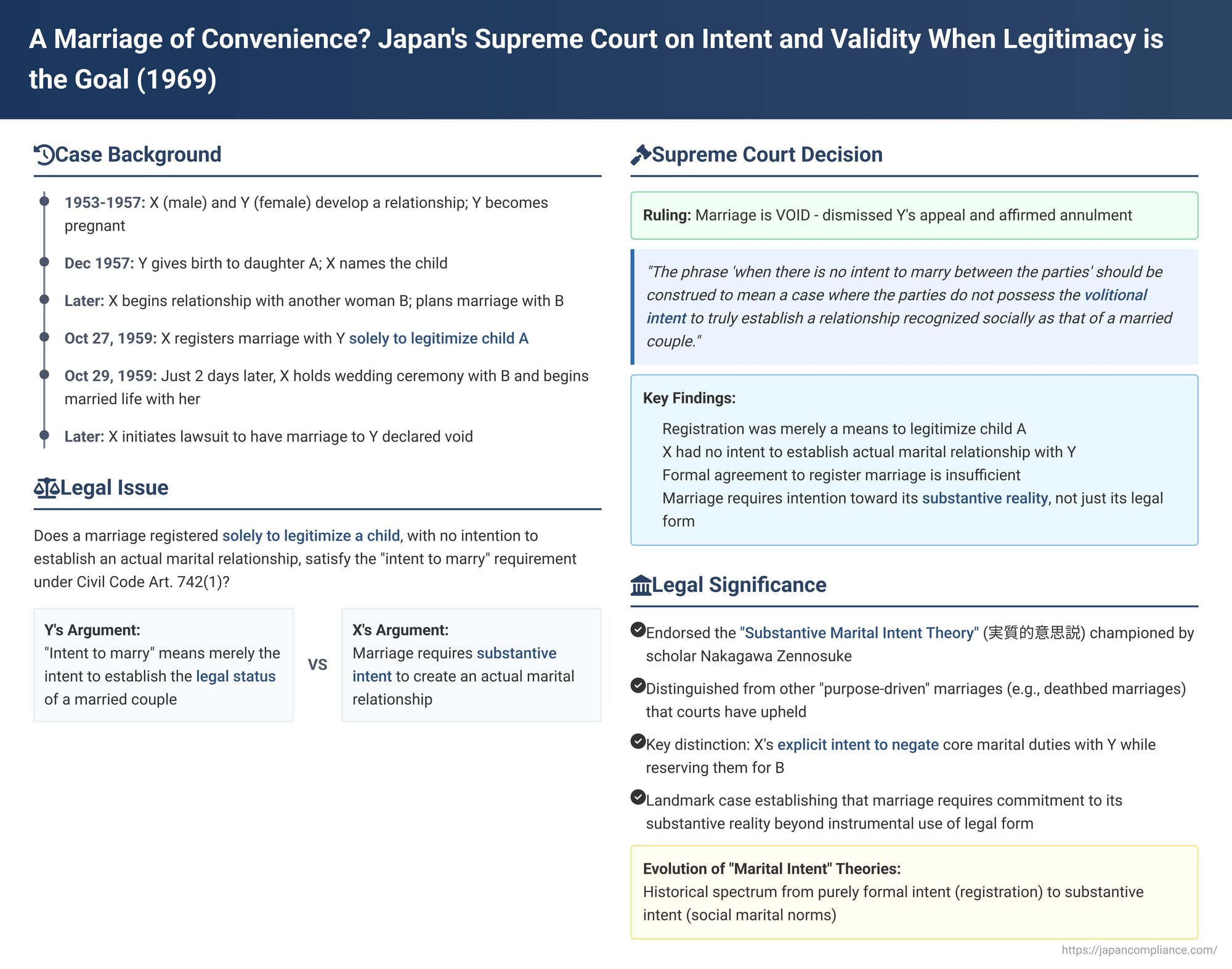

The intent to marry is universally recognized as a cornerstone of a valid marriage. But what happens when individuals go through the legal formalities of marriage not with the primary aim of building a life together as spouses, but for a specific, often singular, collateral purpose? A common, and often sympathetically viewed, scenario involves parents who register a marriage solely to confer legal legitimacy on their child. Is such a "marriage of convenience" or "paper marriage" valid under Japanese law? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this delicate and profound question in a landmark decision on October 31, 1969 (Showa 42 (O) No. 1108).

The Background: A Tumultuous Relationship and a Child's Status

The case involved a man, X, and a woman, Y, whose relationship had a complex and fraught history. Y began working at a health center in Osaka city in 1952. In August 1953, she started lodging at the home of her supervisor and, from September of that year, developed a sexual relationship with the supervisor's son, X, who was then a university student. They promised to marry each other.

However, X's parents were opposed to the union. Even after Y moved out of X's parents' home in September of the following year, their relationship continued, during which time Y underwent three abortions. In March 1957, X graduated from university and secured employment in Ibaraki prefecture. Around this time, Y became pregnant for the fourth time.

Determined to have the child, Y moved to Tokyo in November 1957, renting a house in X's name. X would visit her on his holidays, send money, and offer encouragement. In December 1957, Y gave birth to their daughter, A, whom X named. Although X was reportedly making preparations for their marriage registration, it was not completed before Y returned to Osaka and resumed her work at the health center. X continued to correspond with Y and occasionally send money.

Subsequently, X became involved with another woman, B, and plans were made for their wedding, with a date set for the ceremony. To resolve his situation with Y, X met her and informed her of his intention to marry B. Discussions ensued involving Y and her family. Arising from these discussions, and due to Y's strong desire to at least have their child, A, registered as legitimate, X reluctantly agreed to a "marriage of convenience". The plan was to formally register a marriage between X and Y to enable A to be entered into the family register as their legitimate child, with the understanding that X and Y would divorce shortly thereafter. X even provided Y with a written pledge to this effect.

Following this agreement, X and Y's marriage was officially registered on October 27, 1959. Just two days later, on October 29, 1959, X proceeded with his marriage ceremony to B and began his married life with her. His subsequent contact with Y was limited to correspondence concerning family registration matters.

The Legal Challenge: Defining the "Intent to Marry"

Some time later, X initiated legal proceedings to have his marriage to Y declared null and void. Y, in turn, filed a counterclaim for solatium (damages for emotional distress). Both the first and second instance courts ruled in favor of X, finding the marriage to Y void. (Y's counterclaim was dismissed at the first instance but she was awarded 1.5 million yen at the second instance ).

Y appealed the annulment to the Supreme Court. Her core argument was that the "intent to marry" required by law should be interpreted merely as the "intent to establish the legal status of a married couple". Since they had both agreed to the registration and its immediate legal effect (making Y X's legal wife, which was a prerequisite for A's legitimation through their marriage), she contended that sufficient marital intent existed.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision: Substance Over Form

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, thereby affirming the annulment of the marriage. Its reasoning provided a crucial clarification on the meaning of "intent to marry" under Article 742, item 1 of the Japanese Civil Code, which states that a marriage is void if "there is no intent to marry between the parties."

Defining Marital Intent Beyond Legal Formalities:

The Court declared: "[T]he phrase 'when there is no intent to marry between the parties' should be construed to mean a case where the parties do not possess the volitional intent (効果意思 - kōka ishi) to truly establish a relationship recognized socially as that of a married couple."

Purpose of Registration vs. True Marital Intent:

The Court elaborated that even if there is a mutual agreement between the parties concerning the marriage notification itself, and even if it can be acknowledged that the parties, for a time, possessed the intent to establish the legal status of a married couple (as Y argued), the marriage is still void if this legal formality "was merely a means feigned to achieve another objective, and if, as stated above, there was no volitional intent to truly establish a marital relationship."

Application to X and Y's Marriage:

Applying this definition to the facts of the case, the Supreme Court found: "Regarding the notification of the marriage in this case, there was an agreement between X [the appellee] and Y [the appellant] for the marriage notification as a means to grant A the status of a legitimate child between them. However, X did not have the volitional intent to truly establish a marital relationship with Y as described above. Therefore, the appellate court's judgment that the said marriage did not come into effect is justifiable." The Court also distinguished a precedent cited by Y concerning divorce intent as being different and not applicable to the present case.

The "Substantive Marital Intent" Theory and Its Influence

This Supreme Court decision is widely seen as aligning with, or at least heavily influenced by, the "substantive marital intent" theory (実質的意思説 - jisshitsu-teki ishi setsu). This theory, notably championed by the influential Japanese legal scholar Dr. Nakagawa Zennosuke, posits that for a status-creating act like marriage to be valid, the parties' intent must go beyond the mere desire to achieve the act's legal formalities or isolated legal effects. Instead, it requires a genuine intention to create the actual social and familial reality associated with that status—in the case of marriage, the intent to live as husband and wife in a manner recognized by societal norms and customs.

Dr. Nakagawa argued that the volitional intent in such "status acts" is inextricably linked to the factual substance of that status, as understood by the society and customs of the era. This contrasts with a more "formal intent" theory (形式的意思説 - keishiki-teki ishi setsu), which might argue that an intent to complete the legal registration is sufficient.

Pre-war Japanese case law on marital intent was relatively scarce, though there were instances where marriages or adoptions were voided if the "true intent" to create the respective relationship was lacking, even if the parties agreed to the registration for other purposes (e.g., an adoption solely to facilitate a woman's marriage into a family of higher status, or to evade military service). The 1969 Supreme Court ruling provided a much clearer articulation of this "substantive" approach at the highest judicial level for marriage.

Distinguishing from Other "Purpose-Driven" Marriages: The Case of Deathbed Marriages

The ruling that a marriage solely to legitimize a child is void might seem, at first glance, to conflict with judicial tolerance for other types of "purpose-driven" marriages, such as "deathbed marriages" (臨終婚 - rinjūkon). These are marriages often registered when one party is terminally ill, primarily to allow the surviving partner to inherit or receive survivor benefits. Japanese courts have, in some instances, upheld the validity of such marriages without extensively questioning the depth of "marital intent" beyond the desire for these legal consequences, even when one party was unconscious at the time of registration and died shortly thereafter.

However, legal commentary suggests a basis for distinguishing these situations from the one in X and Y's case. In many deathbed marriage scenarios, there might be an underlying, albeit perhaps abstract or short-lived, intent to embrace the entirety of the marital status and its legal effects (including, but not limited to, inheritance or pension rights). The parties are not typically simultaneously and explicitly excluding core components of a marital relationship.

In X and Y's case, the situation was different. X had a clear and contemporaneous intention to marry another woman, B, and to establish a genuine marital life with her. His "marriage" to Y was not only for the sole purpose of legitimizing A but was also accompanied by an explicit intention to not fulfill the fundamental duties of a marital relationship with Y—such as cohabitation, mutual support, cooperation, and fidelity—as he intended to reserve these for his relationship with B. It was this active and manifest exclusion of the essential substance of a marital bond with Y, beyond the narrow legal aim concerning A, that proved critical in the Court's decision to declare the marriage void.

The Evolving Landscape of Marital Intent Theories

The legal understanding of "marital intent" has evolved. Historically, views ranged from the purely formal (intent to register) to the profoundly substantive (intent to live according to social marital norms). A dominant modern theory in Japanese academia tends to focus on whether there is an intent directed towards the legally defined effects of marriage. Under a strict application of this "legal effects intent" theory, one might argue that X and Y's marriage should be valid because legitimizing a child is indeed a recognized legal effect of marriage.

However, as noted by the legal commentary on this 1969 case, a nuanced application, even of this dominant modern theory, can support the Supreme Court's conclusion. If one considers X's explicit and demonstrable intent to negate the core relational aspects and duties of marriage with Y (because those were directed towards B), then it can be argued that the requisite comprehensive intent towards the legal effects of marriage with Y was absent. This allows for a consistent understanding where this marriage is voided, while deathbed marriages (where such explicit negation of core marital duties with the dying spouse is usually not present) can still be upheld.

Conclusion: The Essence of Marriage Beyond Legal Form

The Supreme Court of Japan's 1969 decision in this case remains a pivotal judgment in family law. It powerfully underscores the principle that for a marriage to be valid, there must be more than a mere agreement to undergo the legal registration process for a limited purpose. The law requires a genuine "volitional intent to truly establish a relationship recognized socially as that of a married couple."

While the desire to provide a child with legal legitimacy is an understandable and humane motive, this ruling clarifies that such a motive alone cannot sustain a marriage if the fundamental intention to create a true spousal relationship is absent, particularly when one party actively intends to form such a relationship with another. The case serves as a vital reminder that the institution of marriage, in the eyes of Japanese law, demands a commitment to its substantive reality, not just an instrumental use of its legal form.