A Line and a Point: How Japan's Supreme Court Defined a "Single Act" in a Landmark Drunk Driving Case

When a single course of conduct violates multiple laws, how should the legal system respond? Should it be treated as one composite crime or as several distinct offenses to be punished separately? This fundamental question of criminal law—known in Japan as the theory of the number of crimes—was decisively answered by the Supreme Court of Japan in a landmark Grand Bench decision on May 29, 1974.

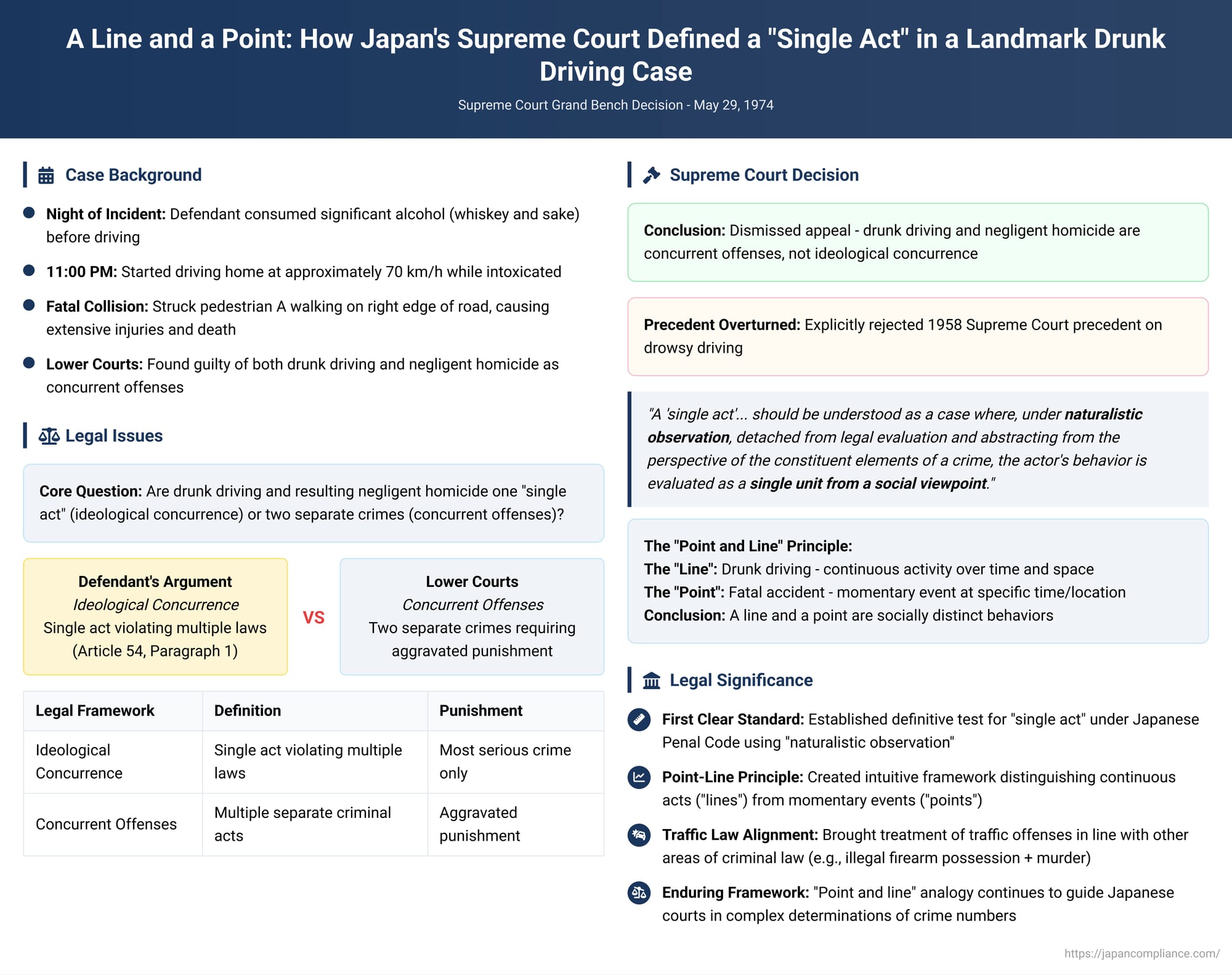

The case involved a drunk driver who caused a fatal accident. The Court was asked to determine the relationship between the crime of drunk driving and the crime of negligent homicide. In its ruling, the Court not only overturned its own precedent but also established an authoritative and enduring definition of what constitutes a "single act" (ikko no kōi) under the Japanese Penal Code, introducing a powerful "point and line" analogy that continues to influence Japanese jurisprudence to this day.

The Factual Background

On the night of the incident, the defendant consumed a significant amount of alcohol, including whiskey and sake, before deciding to drive home around 11:00 PM. While driving his car at approximately 70 km/h, his state of intoxication made it difficult for him to focus on the road ahead. The law imposed a clear duty on him to immediately stop driving in such a condition to prevent an accident.

He failed to do so. Continuing to drive while impaired, he struck a pedestrian, identified as A, who was walking on the right edge of the road. A suffered extensive injuries from the collision and died.

The Legal Question: One Act or Two?

The lower courts—the Shizuoka District Court and the Tokyo High Court on appeal—both found the defendant guilty of two separate crimes: drunk driving (in violation of the Road Traffic Act) and negligent homicide causing death (gyōmu-jō kashitsu chishi, a crime that has since been replaced by more specific statutes for vehicular homicide). They treated these as "concurrent offenses" (heigō-zai), which, under Japanese law, typically results in an aggravated punishment that is more severe than the penalty for any single one of the crimes.

The defendant appealed to the Supreme Court. He argued that the two crimes should be considered an "ideological concurrence" (kan-nen-teki kyōgō). This legal concept, defined in Article 54, Paragraph 1 of the Penal Code, applies when a "single act" violates multiple criminal statutes. In such cases, the defendant is punished only for the most serious of the crimes committed. The defense’s argument rested on a 1958 Supreme Court precedent that had found an ideological concurrence between drowsy driving and the resulting negligent homicide, asserting that his case was legally analogous.

The Supreme Court was thus faced with a direct conflict: should drunk driving causing a fatal accident be treated as two separate crimes, or as one single act with two tragic consequences? The answer would hinge entirely on the definition of a "single act."

The Grand Bench Ruling: A Landmark Definition

The Grand Bench, the highest collegial body of the Supreme Court, acknowledged that its ruling would conflict with the 1958 precedent on drowsy driving. It then proceeded to explicitly overturn that precedent, establishing a new and definitive standard.

The Court first laid out its general definition of a "single act" under the Penal Code:

A "single act" ... should be understood as a case where, under naturalistic observation, detached from legal evaluation and abstracting from the perspective of the constituent elements of a crime, the actor's behavior is evaluated as a single unit from a social viewpoint.

Applying this new standard, the Court analyzed the facts of the case. It drew a sharp distinction between the two offenses based on their fundamental nature:

- The "Line" - Drunk Driving: The act of driving a car, the court observed, is inherently continuous. It involves duration over time and movement across space. The crime of drunk driving describes this entire continuous activity.

- The "Point" - The Fatal Accident: In contrast, the act of causing a fatal accident is an event that occurs at a specific, momentary point in time and at a single location during the course of that continuous drive.

From this "naturalistic observation," the Court concluded that a continuous line and a single point are, from a social perspective, two separate and distinct things. They cannot be viewed as a single unit of behavior.

Therefore, the crime of drunk driving and the crime of negligent homicide causing death are concurrent offenses (heigō-zai), not an ideological concurrence. The Court stated that this conclusion holds true regardless of whether the state of intoxication is considered to be the specific content of the negligence that caused the accident, thereby rejecting more complex theories that had been debated in lower courts.

Analysis and Impact: The "Point and Line" Principle

This 1974 decision is one of the most significant in the history of Japanese criminal law for two primary reasons. First, it provided the first clear, general standard for defining a "single act," a concept that had previously been applied on a more case-by-case basis. Second, its "point and line" analogy created a powerful and intuitive principle for resolving complex questions about the number of crimes.

This principle has been consistently applied in subsequent cases, creating a clear and predictable body of law:

Cases Treated as Concurrent Offenses (A "Line" and a "Point")

The logic of separating a continuous state or act from a momentary event has been applied in other areas. For example, the Court has long held that the crime of illegally possessing a firearm (a continuous state, or a "line") and the crime of committing a murder or robbery with that firearm (a momentary act, or a "point") are concurrent offenses. The 1974 drunk driving ruling brought the treatment of traffic offenses into alignment with this established principle.

Cases Treated as Ideological Concurrence (A "Line" and a "Line")

The power of the "point and line" principle is best understood by contrasting it with cases where the Court did find a single act. On the very same day as the landmark drunk driving decision, the Grand Bench also ruled on two other cases:

- Unlicensed driving and drunk driving.

- Unlicensed driving and driving a vehicle with an expired inspection certificate.

In both of these cases, the Court held that the offenses constituted an ideological concurrence. The reasoning is clear: both drunk driving and unlicensed driving are continuous states that describe the entirety of the same physical act of driving. They are two "lines" that completely overlap for the duration of the criminal conduct. They are, from a naturalistic and social viewpoint, a single unit of behavior that happens to violate two different laws.

Similarly, the Court has found ideological concurrence between a single act of running a red light (a "point") and the resulting negligent injury (also part of the same momentary event at the "point"). This is a "point and point" scenario.

The Ongoing Academic Debate

While the Court’s "naturalistic observation" standard is the law of the land, it is not without its critics in the academic world. The dissenting opinion in the 1974 case, along with many legal scholars, has argued that it is impossible to completely "abstract from the constituent elements of a crime" when determining the number of crimes. The very question of whether one or multiple crimes exist only arises after a legal evaluation has determined that multiple criminal statutes have been violated. These critics argue that the focus should be less on a "naturalistic" view and more on the degree of overlap in the criminal conduct itself that satisfies the elements of each offense.

Conclusion

The 1974 Grand Bench decision remains a cornerstone of Japanese criminal law. By establishing a clear definition of a "single act" and introducing the elegant "point and line" principle, the Supreme Court created a durable framework for distinguishing between single criminal transactions and multiple, concurrent offenses. It settled a major legal debate regarding traffic offenses and provided a standard that, while not without its theoretical critics, has guided Japanese courts for decades in navigating one of the most complex areas of legal doctrine.