A Latent Threat: Japanese Supreme Court on Hepatitis B from Vaccinations, Causation, and Time Limits for Claims

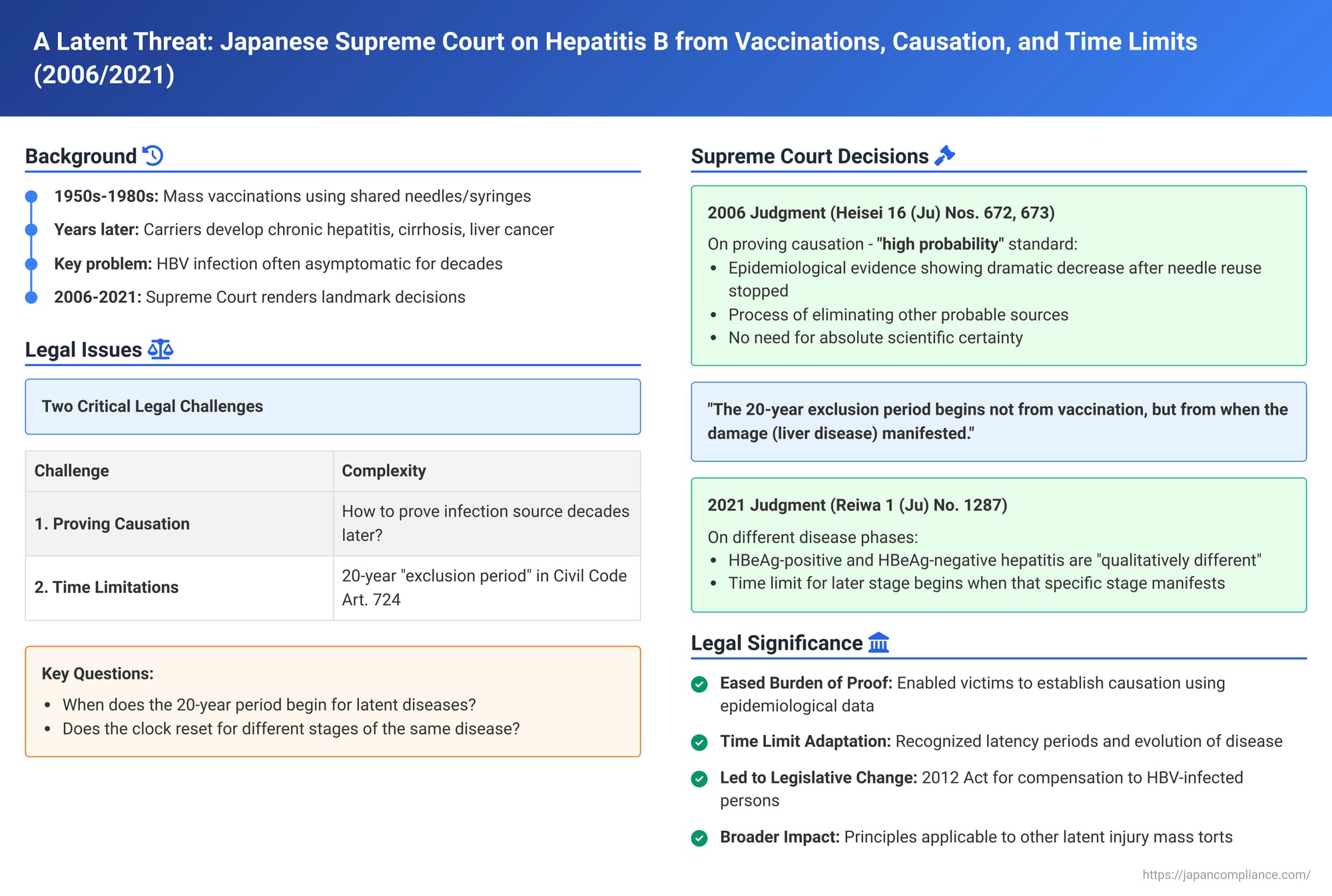

For decades, many individuals in Japan unknowingly contracted Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) during childhood through state-administered mass vaccination programs where needles and syringes were often reused. This practice led to widespread chronic HBV infections, with devastating health consequences such as chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and liver cancer manifesting years or even decades later. Securing legal redress for this harm involved complex battles over proving causation and overcoming strict time limits for filing claims. Two landmark decisions by the Supreme Court of Japan, one on June 16, 2006 (Heisei 16 (Ju) Nos. 672, 673), and a subsequent one on April 26, 2021 (Reiwa 1 (Ju) No. 1287), critically shaped the legal landscape for these victims, particularly concerning the establishment of a causal link and the interpretation of the 20-year "exclusion period" for bringing damage claims.

The Scourge of Hepatitis B via Mass Vaccinations: Background

Hepatitis B is a viral infection that attacks the liver. While adults infected with HBV often recover, infection in infancy or early childhood frequently leads to a chronic carrier state. These carriers may remain asymptomatic for many years, but a significant number eventually develop chronic liver diseases in adulthood. In Japan, a major route of HBV infection for individuals born before the late 1980s was iatrogenic, through the reuse of injection equipment during mass public health initiatives such as tuberculin skin tests and vaccinations for diseases like polio, diphtheria, and smallpox. The plaintiffs in these cases (X1-X7) were individuals who alleged they contracted HBV through such means and subsequently developed related liver diseases. They sued the Japanese State (Y) under the State Compensation Act, alleging negligence in failing to mandate and enforce single-use practices for injection equipment.

The First Landmark: Supreme Court Judgment of June 16, 2006

This pivotal judgment addressed two primary challenges faced by the plaintiffs: definitively proving that their HBV infection was caused by the childhood mass vaccinations, and overcoming the 20-year statutory time limit (known as an "exclusion period" or joseki kikan under the pre-2017 Civil Code Article 724, latter part) for filing tort claims.

1. On Proving Causation:

The Supreme Court began by reaffirming the established standard for proving causation in litigation: "Proof of a causal relationship in a lawsuit does not require scientific proof that allows for no doubt whatsoever, but rather is the proof of a high probability that a specific fact led to a specific result, by comprehensively examining all evidence in light of empirical rules. The determination thereof requires that an ordinary person could hold a conviction of its truthfulness to such a degree as not to harbor doubt, and that is sufficient."

Applying this to the Hepatitis B cases, the Court found a "high probability" of a causal link between the mass vaccinations and the plaintiffs' HBV infections. Key factors supporting this conclusion included:

- HBV is transmitted via blood, and the reuse of syringes during mass vaccinations posed a clear risk of infection if any vaccinated child was an HBV carrier.

- The plaintiffs had all received such mass vaccinations during their early childhood.

- They were subsequently confirmed to be chronic HBV carriers, with their infections acquired in childhood.

- Crucially, evidence indicated that mother-to-child (vertical) transmission was not the source of infection for these plaintiffs.

- The Court gave significant weight to epidemiological evidence showing a dramatic decrease in new chronic HBV carriers among children born after 1986. This was when nationwide programs to prevent mother-to-child HBV transmission were implemented. The success of these programs in nearly eradicating new childhood infections implied that other routes of horizontal transmission (infection from person to person, not mother to child) in early childhood, apart from the reuse of needles in mass vaccinations, must have been "extremely low."

- No other specific, high-probability sources of infection were identified for these plaintiffs during their early childhoods.

Based on this comprehensive assessment, the Court concluded that it was highly probable the plaintiffs were infected due to the reuse of syringes during the mass vaccination programs.

2. On the 20-Year Exclusion Period:

The pre-2017 Civil Code Article 724 stipulated a 20-year period from "the time of the tortious act" after which a claim for damages was extinguished. The lower appellate court had started this clock from the date of the plaintiffs' last vaccination.

The Supreme Court, however, adopted a more victim-protective interpretation, consistent with its precedents in other latent injury cases (like pneumoconiosis and Minamata disease):

- For torts where damage arises only after a considerable latency period following the wrongful act (as is the case with chronic Hepatitis B developing from childhood infection), the 20-year exclusion period begins not from the time of the wrongful act (the vaccination), but from "when all or part of the said damage occurred."

- In the context of Hepatitis B, this "occurrence of damage" was interpreted as the onset of the actual liver disease (e.g., chronic hepatitis) in adulthood, not the initial, often asymptomatic, HBV infection in childhood.

This interpretation was vital, as it prevented claims from being time-barred before the victims even knew they were ill.

The Second Landmark: Supreme Court Judgment of April 26, 2021

This more recent judgment built upon the principles of the 2006 decision, offering further refinement regarding the starting point of the exclusion period, particularly when a patient experiences different, evolving stages of chronic Hepatitis B disease over many years.

The Scenario and the Question:

The plaintiffs in this second case had also contracted HBV via childhood mass vaccinations. They initially developed HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis (an active phase of the disease). After antiviral treatment, this phase remitted, and they underwent "seroconversion" (becoming HBeAg-negative, indicating lower viral replication). However, years later, they developed HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis, a distinct phase that can also be serious and progressive, often involving more advanced liver fibrosis and a lower chance of spontaneous remission.

The legal question was: For claiming damages specifically related to the later onset of HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis, did the 20-year exclusion period begin from the onset of the initial HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis, or from the later onset of the HBeAg-negative phase? The Fukuoka High Court had ruled that both phases were part of the same continuous illness, starting the clock from the first hepatitis diagnosis.

The Supreme Court's Refinement:

The Supreme Court disagreed with the High Court and held:

- The damage resulting from the onset of HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis and the damage resulting from the subsequent onset of HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis (especially after a period of remission and seroconversion) are "qualitatively different" (shitsuteki ni kotonaru mono).

- This distinction was based on the differing clinical characteristics and prognosis of the two phases. The Court noted that while many HBeAg-positive patients seroconvert and become inactive carriers with a good long-term prognosis, a subset (10-20%) later develop HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis, a condition whose specific triggering mechanisms were not fully understood medically.

- Therefore, the 20-year exclusion period for damages specifically arising from the onset of HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis starts from the time of the onset of the HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis itself. The Court reasoned that it would have been impossible for the plaintiffs to claim damages for this later, distinct stage of the disease at the time their initial HBeAg-positive hepatitis first manifested.

Impact and Significance of These Rulings

These two Supreme Court decisions have had a profound impact:

- Eased Burden of Proof for Causation: The 2006 judgment provided a crucial pathway for victims of this mass exposure to establish a causal link between the vaccinations and their illness by effectively using epidemiological data and the process of eliminating other probable causes. This was particularly important given the lack of direct evidence (like preserved syringes) decades later.

- Fairer Application of Time Limits for Latent and Evolving Diseases: Both judgments, especially the 2006 ruling and its 2021 refinement, significantly adapted the strict 20-year exclusion period to the realities of latent diseases that can take decades to manifest and can evolve through qualitatively different stages. This ensured that victims were not unfairly deprived of their right to claim damages before their illness became apparent or before subsequent, distinct forms of damage emerged.

- Paving the Way for Broader Relief: These judicial victories, and the consistent findings of state negligence in numerous lower court cases, applied immense pressure on the government. This ultimately led to a "Basic Agreement" between the national plaintiffs' group/legal team and the State, followed by the enactment in 2012 of the "Act on Special Measures for Payment of Benefits to Specific Hepatitis B Virus Infected Persons." This Act created a non-litigation framework for providing standardized compensation (benefits) to a large number of individuals infected through these past vaccination practices, aiming for a quicker and more comprehensive resolution.

- Relevance for Other Latent Injury Cases: The principles articulated by the Supreme Court regarding the starting point of long-term claim periods for latent injuries have broader relevance beyond Hepatitis B cases and continue to inform legal interpretation in similar mass tort scenarios involving delayed harm.

- Note on the 2017 Civil Code Reform: It's important to note that the pre-2017 Civil Code's 20-year "exclusion period" (Art. 724, latter part) has been reformed. Under the revised Civil Code (effective 2020), this 20-year period is now explicitly termed a "statute of limitations" (Art. 724, No. 2). This means it is subject to standard rules for statutes of limitations, including the requirement that it be invoked as a defense by the defendant, and potentially allows for more flexibility in its application (e.g., arguments about abuse of rights in invoking the defense).

Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan, through its landmark decisions in 2006 and 2021, demonstrated a significant commitment to ensuring access to justice for the many victims of Hepatitis B contracted through state-administered mass vaccination programs decades ago. By establishing a strong basis for proving causation and by interpreting the 20-year time limit for claims in a manner that recognized the latent and evolving nature of the disease, the Court not only provided a path for individual redress but also played a critical role in prompting a broader legislative and social resolution to this tragic public health legacy. These rulings stand as important precedents in Japanese tort law concerning mass exposure, latent injuries, and the state's responsibility for public health programs.