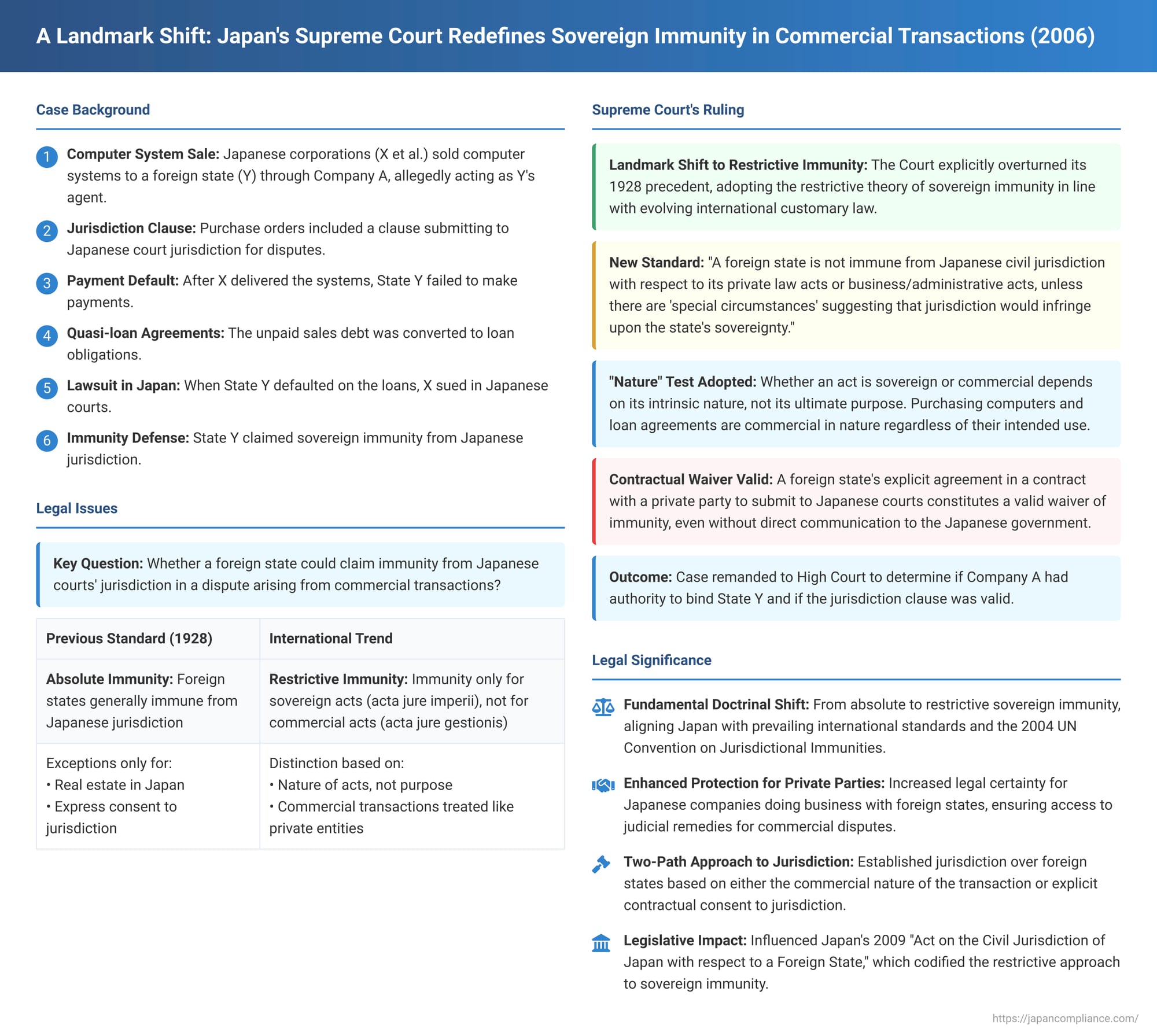

A Landmark Shift: Japan's Supreme Court Redefines Sovereign Immunity in Commercial Transactions

In an era of globalized commerce, disputes arising from contracts between private entities and foreign states present complex legal challenges, primarily centered on the doctrine of sovereign immunity. This doctrine traditionally shielded states from the jurisdiction of foreign courts. However, evolving international norms have led many nations to adopt a more nuanced approach. On July 21, 2006, the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a seminal judgment in a loan recovery case, marking a historic departure from its long-standing adherence to absolute sovereign immunity and embracing the principle of restrictive immunity. This decision has profound implications for international trade and investment involving foreign governmental entities in Japan.

The Factual Background: A Deal, A Default, and A Dispute Over Jurisdiction

The case involved Japanese corporations, X et al. (the plaintiffs/appellants), and a foreign state, State Y (the defendant/appellee). The dispute originated from contracts for the sale of high-performance computer systems by X et al. to State Y. These transactions were purportedly conducted through Company A, an entity associated with State Y’s Ministry of Defense and acting as State Y’s agent.

Crucially, the purchase orders, issued in the name of Company A's representative, included a clause explicitly stating that in the event of any dispute arising from the contracts, State Y agreed to submit to the jurisdiction of Japanese courts. X et al. fulfilled their contractual obligations by delivering the computer systems. However, State Y allegedly failed to make the required payments.

To address the outstanding debt, X et al. and State Y (reportedly through Company A) subsequently entered into quasi-loan agreements. These agreements essentially converted the unpaid sales debt into a formal loan obligation. It was also understood that the jurisdiction clause from the original purchase orders was incorporated into these quasi-loan agreements.

When State Y continued to default on its payment obligations under the quasi-loan agreements, X et al. initiated legal proceedings in Japan. They sought recovery of the principal loan amount, along with contractually stipulated interest and damages for late payment. In response, State Y asserted sovereign immunity, arguing it was exempt from the jurisdiction of Japanese courts, and contested the claim that Company A had the authority to represent it or to agree to the contracts.

The Lower Courts: A Clash of Interpretations on Sovereign Immunity

The case then embarked on a journey through the Japanese judicial system, revealing conflicting interpretations of sovereign immunity.

The Court of First Instance (Tokyo District Court):

At the initial stage, State Y was duly summoned but chose not to appear before the Tokyo District Court, nor did it submit any written defense or pleadings. Under Japanese civil procedure, this failure to contest the claims can lead to a "deemed admission" of the factual allegations presented by the plaintiff. Consequently, the District Court ruled in favor of X et al., upholding their claims.

State Y's Appeal to the Tokyo High Court:

State Y appealed this decision to the Tokyo High Court. Its central argument was that, as a sovereign nation, it was entitled to immunity from the civil jurisdiction of Japanese courts. Therefore, it contended that the lawsuit itself was inadmissible and should be dismissed.

The Tokyo High Court sided with State Y. Its decision was heavily reliant on a long-standing precedent set by the Great Court of Cassation (the precursor to the Supreme Court) in its decision of December 28, 1928 (often referred to as the Matsuyama case). This precedent had entrenched the doctrine of absolute immunity in Japanese jurisprudence.

According to this doctrine, foreign states were, as a general rule, completely immune from the civil jurisdiction of Japanese courts. Exceptions were very limited, typically confined to disputes concerning real estate owned by the foreign state within Japan or instances where the foreign state expressly consented to jurisdiction for a specific case.

The High Court reasoned that for a waiver of immunity to be effective, it required a clear expression of intent from the foreign state directly to the Japanese state – for example, through a bilateral treaty. Alternatively, a state might waive immunity by its own actions within a specific lawsuit, such as by initiating proceedings itself or by taking steps that implicitly acknowledged the court's authority.

Critically, the High Court found that the jurisdiction clause contained within the purchase orders and quasi-loan agreements did not meet this stringent test. Even if Company A was State Y's agent and had agreed to the clause, this agreement was made with X et al., private commercial entities. It was not an expression of intent made by State Y to the state of Japan. As there was no evidence that State Y had otherwise communicated to Japan a desire to waive its immunity for this type of dispute, the High Court concluded that State Y remained immune. Accordingly, it reversed the District Court's ruling and dismissed X et al.'s lawsuit.

X et al.'s Appeal to the Supreme Court:

Dissatisfied with the High Court's decision, X et al. appealed to the Supreme Court of Japan. Their core contention was that the High Court had erred in its interpretation and application of the principles of sovereign immunity, particularly in light of contemporary international law and state practice.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision: Embracing Restrictive Immunity

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of July 21, 2006, undertook a comprehensive re-evaluation of the doctrine of sovereign immunity, ultimately leading to a landmark shift in Japanese law.

1. Sovereign Immunity in International Law: An Evolving Landscape

The Court began by acknowledging the historical context: absolute immunity, where foreign states were generally shielded from jurisdiction for nearly all their acts, was indeed the dominant theory in the past and reflected in customary international law. However, the Court emphasized that the landscape of international law and state practice had undergone a significant transformation.

Several factors contributed to this evolution. The expanding scope of state activities, particularly their increasing involvement in commercial and economic ventures that were previously the domain of private entities, necessitated a re-think. This led to the emergence and gradual acceptance of the doctrine of restrictive immunity.

Restrictive immunity draws a crucial distinction:

- Acta jure imperii (sovereign or public acts): These are acts that a state performs in the exercise of its sovereign authority (e.g., diplomatic relations, military activities, legislative acts). For these acts, immunity generally continues to be recognized.

- Acta jure gestionis (private, commercial, or administrative acts): These are acts of a commercial or private law nature that could equally be performed by private individuals or corporations (e.g., ordinary commercial contracts, employment contracts for administrative staff, leasing property). The restrictive immunity doctrine posits that states should not be immune from jurisdiction for these types of acts.

The Supreme Court noted that a great number of countries had already incorporated the restrictive immunity principle into their domestic legal systems through legislation or judicial decisions. Furthermore, it pointed to the United Nations Convention on Jurisdictional Immunities of States and Their Property (adopted by the UN General Assembly in December 2004, though not yet in force at the time of this judgment). This Convention also firmly endorsed the restrictive immunity approach.

Based on this global trend and evolving state practice, the Supreme Court concluded that while customary international law still supported immunity for a foreign state’s sovereign acts, it no longer upheld the principle that foreign states are also immune for their private law or business/administrative acts.

2. Restrictive Immunity Under Japanese Law: A New Standard

Having established the shift in international customary law, the Supreme Court then considered how this should apply within Japan's legal framework.

The Court explained that the traditional rationale for sovereign immunity stems from the principles of par in parem non habet imperium (an equal has no power over an equal) and the mutual respect for the sovereignty of independent states. However, it reasoned that if a foreign state engages in private or business/administrative activities, subjecting it to the jurisdiction of Japanese courts for disputes arising from those activities would not normally infringe upon its sovereignty or dignity as a state.

Since the core justification for immunity (protecting sovereignty) does not typically apply to such private acts, the Court found no compelling rational basis for granting immunity in these circumstances. Indeed, to continue to grant absolute immunity, even in cases where the foreign state's sovereignty is not genuinely at risk, would lead to manifestly unfair outcomes. It would unilaterally deny private parties, who have entered into transactions with the foreign state, any form of judicial redress for legitimate grievances, often without any reasonable justification.

Therefore, the Supreme Court laid down a new standard for Japan: A foreign state is not immune from the civil jurisdiction of Japanese courts with respect to its private law acts or its business/administrative acts, unless there are "special circumstances" suggesting that the exercise of jurisdiction by a Japanese court would, in that particular instance, constitute an infringement upon the sovereignty of the foreign state concerned.

3. Waiver of Immunity: Including Contracts with Private Parties

The Court also addressed the issue of waiver of immunity. It reaffirmed established principles: a foreign state is not immune if it explicitly consents to Japanese jurisdiction through an international agreement (such as a treaty with Japan) or if it voluntarily submits to the jurisdiction of a Japanese court in a particular case (for example, by initiating a lawsuit itself or by defending a claim on its merits without raising an immunity defense).

Significantly, the Supreme Court expanded on the concept of waiver. It held that a foreign state would also generally not be immune from Japanese jurisdiction if it explicitly agrees, in a written provision within a contract concluded with a private party, to submit to the jurisdiction of Japanese courts for disputes arising from that contract.

The Court provided two key reasons for this position:

- No Infringement of Sovereignty: In such cases, where the state has contractually agreed to a specific forum, allowing Japanese courts to exercise jurisdiction based on that agreement would not typically be considered an affront to the foreign state's sovereignty. The state itself has chosen to accept this possibility.

- Good Faith and Fairness: For a foreign state to enter into a contract containing such a jurisdiction clause, and then later attempt to renege on that agreement by asserting immunity, would be contrary to the principles of good faith and fairness that should govern contractual relationships. It would undermine the legitimate expectations of the private contracting party.

4. Overturning Long-Standing Precedent

In a clear and decisive move, the Supreme Court explicitly stated that its previous ruling, the Great Court of Cassation decision of December 28, 1928 (which had upheld absolute immunity), was to be overturned to the extent that it conflicted with the principles articulated in the present judgment. This marked a monumental shift, departing from nearly eight decades of established case law.

5. Determining the Nature of State Acts: "Nature" over "Purpose"

A critical aspect of applying restrictive immunity is classifying state acts as either sovereign (jure imperii) or private/commercial (jure gestionis). The Supreme Court provided guidance on this by endorsing the "nature of the act" test over the "purpose of the act" test.

This means that the classification of an act depends on its intrinsic character – whether it is an act that any private individual or company could perform (e.g., buying goods, taking a loan, hiring staff for non-governmental roles). The ultimate purpose for which the state performs the act (e.g., purchasing computers for national defense, as was potentially the case here) does not transform an inherently commercial act into a sovereign one for immunity purposes.

In the specific case before it, the Court observed that the alleged actions of State Y – entering into sales contracts for high-performance computers and subsequently concluding quasi-loan agreements to cover the unpaid price – were, by their very nature, commercial transactions. These are activities that private persons or corporations routinely undertake. Therefore, regardless of the ultimate intended use of the computers, these transactions were to be categorized as private law or business/administrative acts.

Application to the Facts and Remand to the High Court

Applying these newly articulated principles to the facts of the case as alleged by X et al., the Supreme Court reasoned as follows:

- Nature of the Acts: The contracts for the sale of computers and the subsequent quasi-loan agreements, if their existence and State Y's involvement were proven, would constitute private law or business/administrative acts. Consequently, State Y would not be entitled to immunity for these acts unless it could demonstrate "special circumstances" – namely, that the exercise of Japanese jurisdiction would infringe its sovereignty.

- The Jurisdiction Clause: The record indicated that the purchase orders, purportedly issued by Company A as an agent for State Y, contained a clause stipulating consent to the jurisdiction of Japanese courts in case of disputes. Furthermore, it was suggested that this jurisdiction clause was incorporated by reference into the subsequent quasi-loan agreements.

- Potential Waiver: If it were established that Company A was indeed acting as State Y’s authorized agent in these transactions, then the jurisdiction clause could be regarded as an explicit written agreement by State Y to submit to Japanese civil jurisdiction for disputes arising from these contracts. This would provide an independent ground for Japanese courts to exercise jurisdiction, based on waiver.

The Supreme Court found that the Tokyo High Court had erred. By rigidly adhering to the outdated precedent of absolute immunity (the 1928 decision), the High Court had dismissed X et al.'s suit without undertaking a full examination of the crucial factual issues under the correct legal standard. These issues included the precise nature of State Y’s involvement, the scope of Company A’s agency (if any), the specific terms of the contracts, and the effect of the jurisdiction clause. This failure to properly consider the case under the lens of restrictive immunity and the rules on contractual waiver constituted a clear error of law affecting the judgment.

Consequently, the Supreme Court quashed the judgment of the Tokyo High Court and remanded the case back to the High Court for further proceedings. This meant the High Court would have to re-examine the evidence and arguments, applying the principles of restrictive immunity and waiver as laid down by the Supreme Court. This would involve making factual determinations on issues such as whether Company A had the authority to bind State Y and whether the contractual clauses effectively constituted consent to jurisdiction.

Broader Significance and Subsequent Developments

The Supreme Court's 2006 judgment is undeniably a landmark decision in Japanese legal history. Its significance extends far beyond the specific dispute between X et al. and State Y:

- Fundamental Shift in Doctrine: It officially moved Japanese law from the doctrine of absolute sovereign immunity to that of restrictive sovereign immunity, a position already adopted by most major trading nations.

- Alignment with International Norms: This change brought Japan’s approach to sovereign immunity into closer alignment with prevailing international standards and the principles embodied in the UN Convention on Jurisdictional Immunities of States and Their Property.

- Enhanced Legal Certainty and Protection for Private Parties: For private individuals and corporations engaging in commercial transactions with foreign states or their entities in Japan, the decision provided greater legal certainty and an enhanced prospect of obtaining judicial remedies in Japanese courts if disputes arose. It signaled that states engaging in ordinary commercial activities could generally be held accountable in the same way as private parties.

- Adoption of the "Nature of the Act" Test: The Court’s endorsement of the "nature of the act" test over the "purpose of the act" test provided important clarification on how state activities would be characterized for immunity purposes, further aligning Japanese practice with common international approaches.

- Influence on Legislation: The principles articulated by the Supreme Court in this judgment were highly influential in the subsequent drafting and enactment of Japan’s Act on the Civil Jurisdiction of Japan with respect to a Foreign State, etc. This Act, passed in 2009 and entering into force on April 1, 2010, effectively codifies the restrictive approach to sovereign immunity. It provides a detailed framework, enumerating specific categories of proceedings in which a foreign state does not enjoy immunity before Japanese courts, including those arising from "commercial transactions."

Conclusion

The July 21, 2006, judgment by the Japanese Supreme Court represents a pivotal moment in the evolution of sovereign immunity law in Japan. By decisively abandoning the anachronistic doctrine of absolute immunity in favor of the more contemporary and widely accepted principle of restrictive immunity, the Court not only modernized Japanese law but also reinforced Japan's position as a predictable and fair jurisdiction for international commerce.

The decision underscored two primary pathways for establishing jurisdiction over a foreign state in commercial matters: first, if the transaction itself is commercial in nature (an act jure gestionis), immunity will generally not apply unless specific sovereign interests are threatened; and second, if the state has, through a contractual provision with a private party, explicitly consented to the jurisdiction of Japanese courts. This ruling has had a lasting impact on Japanese jurisprudence and continues to shape the legal landscape for commercial dealings involving foreign state entities in Japan.