A Landmark Ruling for Transgender Rights in Japan: The METI Restroom Access Case and Employer Obligations

TL;DR

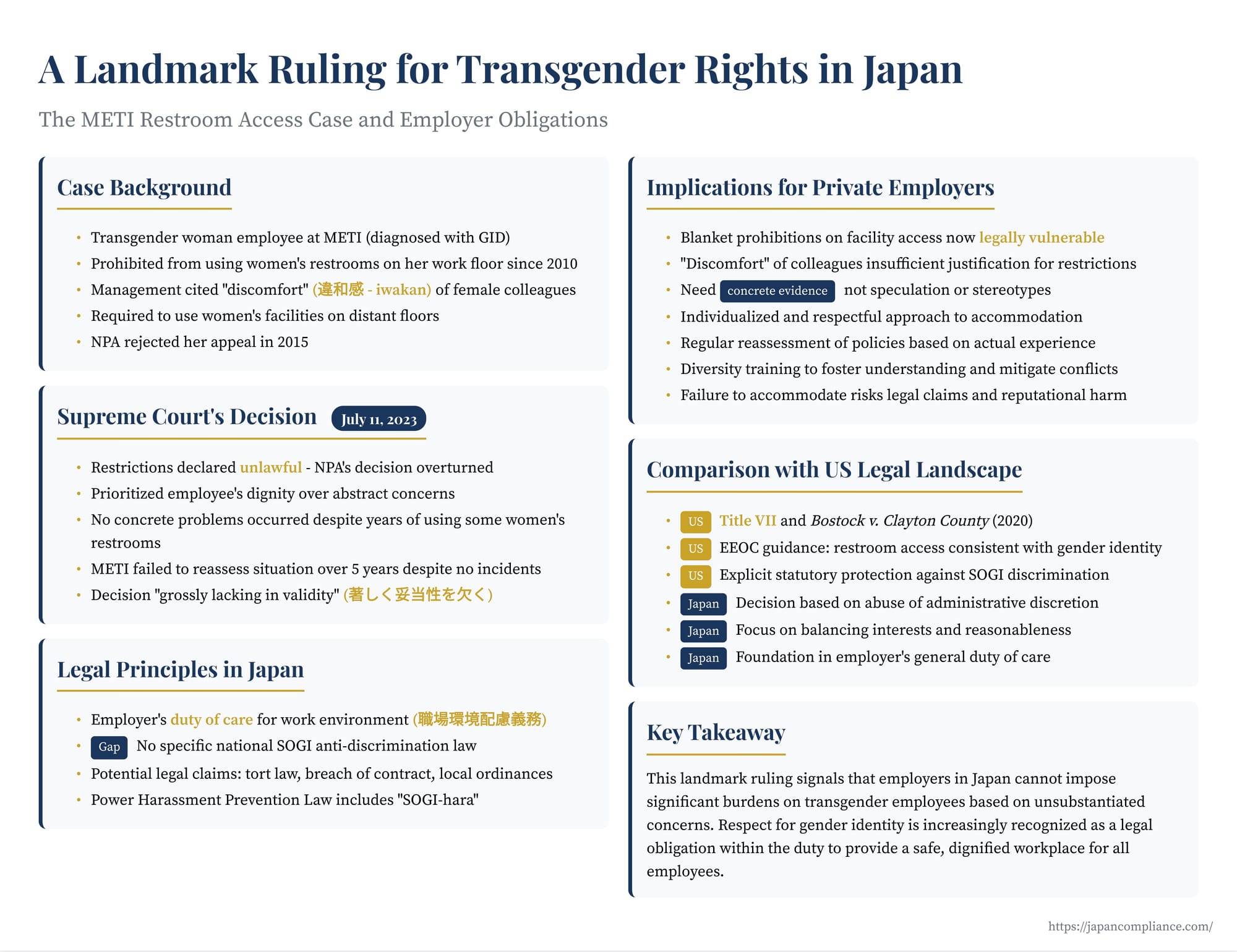

- Japan’s Supreme Court (11 Jul 2023) held that forcing a transgender METI employee to use distant restrooms was an unlawful abuse of discretion, stressing dignity and concrete evidence over abstract “discomfort.”

- Employers’ general duty to maintain a safe, non-discriminatory workplace now clearly covers gender-identity accommodation; blanket bans on restroom access are legally fragile.

- Private employers must assess requests individually, rely on facts (not stereotypes), update policies and train staff to meet evolving SOGI-inclusion expectations.

Table of Contents

- The Case: Background and Journey to the Supreme Court

- The Supreme Court's Decision (July 11 2023): Prioritizing Dignity and Concrete Facts

- Legal Principles and Employer Duties in Japan

- Implications for Private Sector Employers in Japan

- Comparison with the US Legal Landscape

- Conclusion: A Call for Inclusive Workplaces in Japan

Workplace inclusivity and the rights of LGBTQ+ individuals are increasingly prominent topics in corporate governance and human resources management globally. While Japan has made strides in certain areas, it notably lacks comprehensive national legislation explicitly prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity (SOGI). This legal gap often leaves employees and employers navigating complex situations based on general legal principles and evolving case law.

A highly significant development occurred on July 11, 2023, when the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a landmark judgment concerning a transgender employee's right to use workplace restrooms consistent with her gender identity. The case, involving an employee at the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), sets a crucial precedent and offers important guidance—not only for government agencies but also for private sector employers, including foreign companies operating in Japan—on balancing employee rights and fostering an inclusive work environment.

The Case: Background and Journey to the Supreme Court

The plaintiff, a long-serving employee at METI (経済産業省 - Keizai Sangyō Shō), is a transgender woman. Assigned male at birth, she was diagnosed with Gender Identity Disorder (GID)—now more commonly referred to using terms like gender incongruence—and began living socially and professionally as a woman years prior to the core dispute. After medically transitioning (including hormone therapy, though she had not undergone gender confirmation surgery for health reasons), she formally requested permission from METI management to use the women's restrooms on her floor without restriction.

Following an internal meeting in 2010 where the employee's situation was explained to colleagues, METI officials perceived that some female colleagues expressed "discomfort" (違和感 - iwakan). Based on this, METI imposed restrictions: the employee was prohibited from using the women's restrooms on her assigned work floor and the floors immediately above and below it. She was permitted to use women's facilities on floors further away, requiring her to regularly travel two or more floors from her workstation for restroom access.

The employee endured these restrictions for several years before filing a formal request in 2013 with Japan's National Personnel Authority (NPA / 人事院 - Jinjiin)—the body overseeing personnel matters for national public servants—seeking removal of the restrictions under the National Public Service Act (NPSA), which allows employees to request appropriate administrative measures concerning working conditions. In 2015, the NPA rejected her request, upholding METI's restrictions.

The employee then sued the government, seeking to overturn the NPA's decision. The Tokyo District Court ruled in her favor, finding the restrictions illegal. However, the Tokyo High Court reversed this, siding with the government and the NPA. The case ultimately reached the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Decision (July 11, 2023): Prioritizing Dignity and Concrete Facts

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's ruling and reinstated the core finding of the District Court: the NPA's decision to uphold the restroom restrictions was unlawful.

Standard of Review:

The Court first acknowledged that the NPA possesses broad discretion in determining appropriate working conditions for public servants. Therefore, its decisions are subject to judicial review only for abuse of discretion – essentially, whether the decision was grossly lacking in reasonableness.

Balancing Competing Considerations:

The crux of the judgment lay in the Court's assessment of how the NPA (and by extension, METI) balanced the interests involved. The Court meticulously weighed the disadvantage faced by the plaintiff against the stated concerns regarding other employees.

- Recognizing the Plaintiff's Burden: The Court explicitly recognized that the restroom restrictions imposed a significant, non-trivial daily disadvantage (sōō no furieki) on the plaintiff. Being forced to either use restrooms inconsistent with her gender identity or travel considerable distances fundamentally impacted her dignity and working life. The supplemental opinions attached to the judgment further emphasized that living according to one's affirmed gender identity is a crucial legal interest (jūyōna rieki / hōeki) deserving protection.

- Scrutinizing the Employer's Justification: The Court rigorously examined the basis for the restrictions. It found the justification—potential discomfort among some female colleagues—to be insufficient and lacking concrete support, particularly by the time the NPA made its final decision in 2015. Key findings included:

- No Actual Problems: Despite the plaintiff working openly as a woman and using some women's restrooms (on permitted floors) since 2010, no concrete problems or incidents had actually occurred.

- Vague Initial Concerns: The "discomfort" noted initially among a few colleagues was never substantiated as specific objections or safety concerns.

- Failure to Re-evaluate: Critically, neither METI nor the NPA had undertaken any meaningful steps in the nearly five years between the initial colleague meeting and the NPA's final decision to reassess the situation, investigate whether specific employees truly had concerns requiring special consideration, or explore less restrictive alternatives.

- Finding the Balance Tipped: Based on this analysis, the Supreme Court concluded that the NPA's decision upholding the restrictions was an abuse of discretion because it "overly emphasized consideration for other employees without considering the concrete circumstances" and "unjustly minimized the plaintiff's disadvantage." By 2015, the Court found, the risk of trouble arising from the plaintiff using women's restrooms freely was "difficult to assume" (sōtei shigataku), and no specific evidence supported the need for such broad restrictions. The decision was deemed "grossly lacking in validity" (ichijirushiku datōsei o kaku).

In essence, the Supreme Court prioritized the concrete, daily harm experienced by the transgender employee over abstract, unsubstantiated concerns of colleagues, especially given the lack of any actual issues over a significant period.

Legal Principles and Employer Duties in Japan

While this case involved a national public servant and administrative law procedures, its reasoning holds profound implications for private sector employers in Japan due to underlying legal principles governing the employment relationship.

1. Employer's Duty of Care for the Work Environment (Shokuba Kankyō Hairyo Gimu):

Japanese labor law, particularly Article 5 of the Labor Contract Act, imposes a general duty of care on employers to ensure a safe and healthy working environment for their employees. This "duty of care for the work environment" (職場環境配慮義務 - shokuba kankyō hairyo gimu) is interpreted broadly to include psychological safety and protection from discrimination and harassment. The METI case reinforces the idea that this duty extends to ensuring an inclusive and non-discriminatory environment for LGBTQ+ employees, including transgender individuals. Failing to address discriminatory treatment or provide reasonable accommodations could be seen as a breach of this duty.

2. Lack of Specific National SOGI Anti-Discrimination Law:

It remains a critical point that Japan does not have a dedicated national law explicitly prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity in employment. Unlike Title VII in the US (as interpreted by Bostock), employees facing SOGI discrimination in Japan often rely on general legal principles:

- Tort Law (Civil Code Art. 709): Discriminatory acts causing harm could potentially be pursued as torts.

- Breach of Duty of Care/Contract: As mentioned, failure to provide a non-discriminatory environment could breach the employer's duty of care.

- Local Ordinances: Some prefectures and municipalities (like Tokyo) have enacted local ordinances that explicitly prohibit SOGI discrimination, offering stronger protection within those jurisdictions.

3. Power Harassment Prevention Law:

Amendments to the Act on Comprehensively Advancing Labor Measures (commonly known as the Power Harassment Prevention Law) mandate that employers take preventive measures against workplace power harassment. Critically, government guidelines explicitly state that harassment related to sexual orientation or gender identity ("SOGI-hara") falls under the scope of this law. This includes outing someone's SOGI status without consent or engaging in offensive speech or conduct related to it. While distinct from discrimination in terms of conditions, it provides another legal avenue to address hostile work environments based on SOGI status.

Implications for Private Sector Employers in Japan

The Supreme Court's decision in the METI case sends a clear signal to all employers in Japan, including subsidiaries of US companies:

- Restroom Access Policies Need Reassessment: Blanket policies prohibiting transgender employees from using facilities aligned with their gender identity are now highly legally vulnerable. Employers cannot rely on abstract fears or the claimed "discomfort" of other employees as sufficient justification for such restrictions. Concrete evidence demonstrating significant disruption, safety risks, or undue hardship would likely be required, and such justifications may be difficult to meet.

- Individualized and Respectful Approach: Requests for accommodation related to gender transition or gender identity should be handled on a case-by-case basis through respectful dialogue with the employee involved.

- Focus on Concrete Evidence, Not Speculation: If considering any restrictions, employers must base their decisions on tangible evidence and specific circumstances, not on stereotypes or hypothetical concerns. The METI case highlights the importance of reassessing situations over time if initial concerns do not materialize into actual problems.

- Policy Review: Employers should review existing anti-discrimination policies, codes of conduct, facility usage guidelines, and harassment prevention measures to ensure they explicitly or implicitly cover gender identity and align with the principles of non-discrimination and respect highlighted by the Court.

- Training is Key: Implementing diversity and inclusion training that specifically addresses gender identity and transgender issues can help foster understanding among all employees and managers, mitigating potential conflicts based on misinformation or prejudice.

- Legal Risk Management: Failure to provide reasonable accommodations, including appropriate restroom access, exposes employers to potential legal claims (breach of duty of care, tort, violation of local ordinances, power harassment), leading to potential damages, legal costs, and significant reputational harm.

Comparison with the US Legal Landscape

The outcome in the METI case aligns generally with the direction of US federal law regarding restroom access for transgender employees, but the underlying legal frameworks differ.

- US Title VII and Bostock: The US Supreme Court's decision in Bostock v. Clayton County (2020) held that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits employment discrimination "because of... sex," necessarily includes protection against discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

- EEOC Guidance and Case Law: Following Bostock, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and numerous court decisions have affirmed that denying an employee access to restrooms consistent with their gender identity constitutes sex discrimination under Title VII. Employers are generally required to grant access, and concerns of other employees are typically not considered a valid defense.

- State Law Variations: While federal law provides a baseline, specific state and local laws in the US vary, with some offering explicit protections regarding restroom access and others having seen political or legal battles over the issue.

- Key Difference: The METI case reached its conclusion by finding an abuse of administrative discretion within the specific framework of Japanese public service law, focusing heavily on the balancing of interests and the lack of concrete justification for the restriction over time. While deeply significant, it doesn't establish a nationwide statutory right based on non-discrimination in the same way Title VII operates in the US post-Bostock. The foundation in Japan rests more on the employer's general duty of care and the specific facts demonstrating a lack of reasonableness in the employer's actions.

Conclusion: A Call for Inclusive Workplaces in Japan

The Japanese Supreme Court's decision in the METI restroom access case is a landmark victory for transgender rights and workplace inclusion in Japan. While falling short of establishing a broad anti-discrimination right based on statute, it sets a powerful precedent. It signals that employers—both public and private—cannot impose significant burdens on transgender employees based on unsubstantiated fears or the discomfort of others. The ruling underscores the legal importance of recognizing and respecting an individual's gender identity and the employer's fundamental duty to provide a safe, dignified, and inclusive working environment for all employees.

For US companies operating in Japan, this decision reinforces the need to align local HR policies and practices not only with global corporate values but also with the evolving expectations of Japanese law. Moving forward, fostering understanding through education and basing any workplace policies on concrete facts rather than abstract concerns will be crucial for both legal compliance and building a truly inclusive corporate culture in Japan.

- A Step Towards Inclusion: Japan's Supreme Court Rules on Transgender Employee Restroom Access

- A Landmark Shift: Japan's Supreme Court Strikes Down Surgery Requirement for Legal Gender Change

- Human Rights in the Modern Japanese Workplace: Key Developments and Considerations

- MHLW – Guidelines on SOGI Harassment Prevention (Japanese)

- Gender Equality Bureau – Basic Information on LGBT Policy (Japanese)