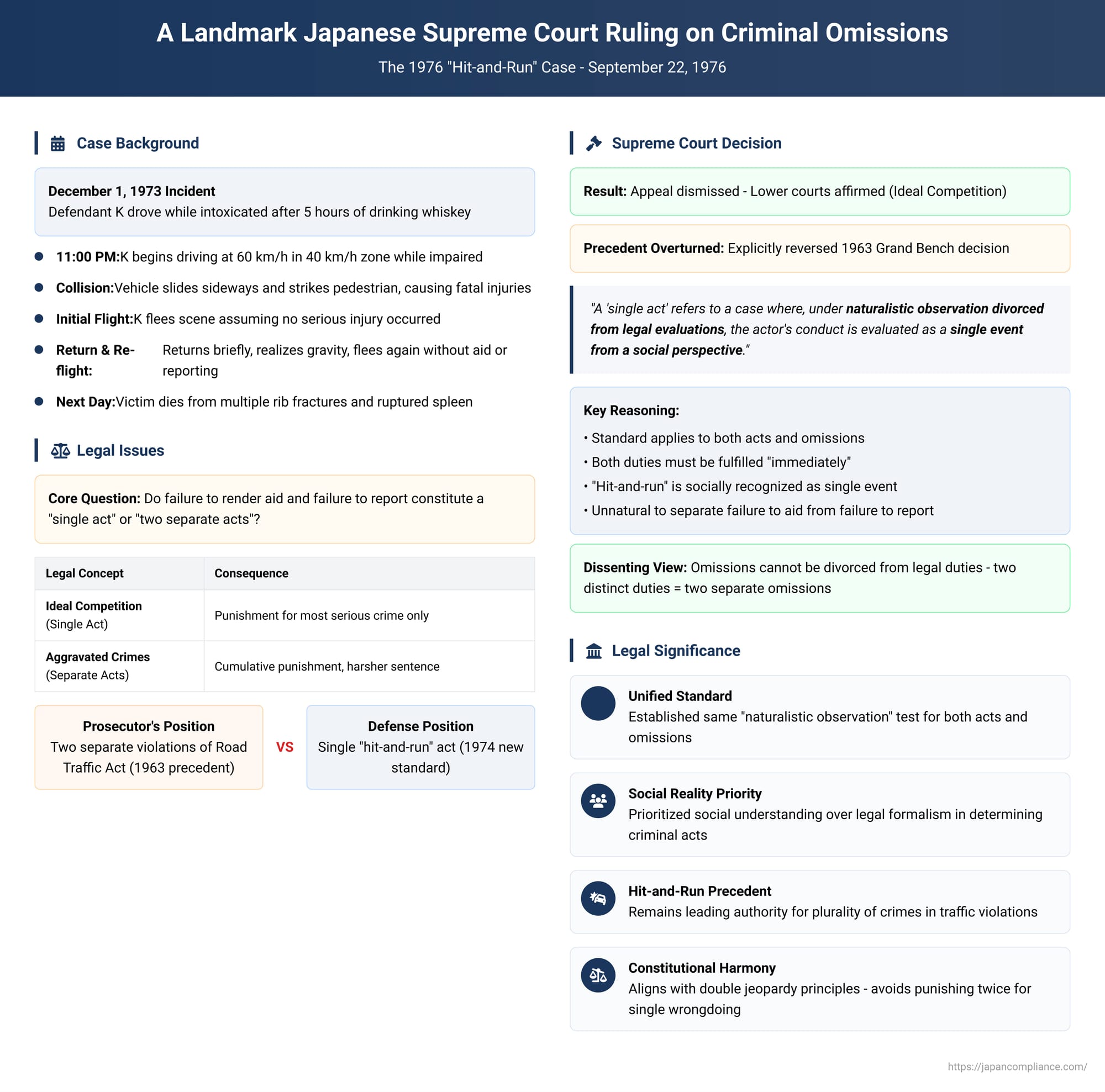

A Landmark Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Criminal Omissions: The 1976 "Hit-and-Run" Case

On September 22, 1976, the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a seminal judgment in a case concerning a fatal hit-and-run incident. The decision, officially known as the "Case of Professional Negligence Causing Death and Violation of the Road Traffic Act," fundamentally reshaped the understanding of how multiple crimes arising from a single course of conduct are treated under Japanese criminal law. At its core, the case grappled with a crucial question: when a driver flees the scene of an accident, failing both to rescue the victim and to report the incident to the police, do these failures constitute two separate criminal acts or a single, unified one? The Court's conclusion to treat them as a single act marked a significant departure from its own precedent and solidified a more holistic, socially-grounded approach to determining the "plurality of crimes," particularly in the context of criminal omissions.

The Facts of the Case

The case arose from a tragic incident on December 1, 1973. The defendant, identified as K, had been drinking whiskey at several establishments for about five hours. Despite being intoxicated to the point where normal driving was difficult, he got behind the wheel with a female companion and drove through a residential area. On a poorly maintained street with a speed limit of 40 km/h, he was traveling at approximately 60 km/h.

Due to his intoxication, K lost control of the vehicle, which slid sideways and struck a pedestrian. The impact caused severe injuries to the victim, including multiple rib fractures and a ruptured spleen, which proved fatal the following day.

Assuming no one had been seriously hurt, K initially fled the scene. However, after his companion repeatedly urged him to return, he went back. Seeing a crowd gathered, he realized the gravity of the situation and understood he had caused a personal injury accident. Fearing the discovery of his drunk driving, he chose to flee again without providing any aid to the injured victim or reporting the accident to the authorities as required by law.

Procedural History and the Central Legal Issue

The defendant, K, was charged with professional negligence causing death under the Penal Code and two separate violations of the Road Traffic Act: failure to render aid (Article 72, Paragraph 1, first sentence) and failure to report the accident (Article 72, Paragraph 1, second sentence).

The District Court found him guilty on all counts. Crucially, it ruled that the two violations of the Road Traffic Act—the failure to aid and the failure to report—were in a state of "ideal competition." The prosecutor appealed, arguing that, based on a 1963 Supreme Court Grand Bench precedent, the two crimes should be treated as "aggravated crimes," which would typically result in a harsher sentence. The High Court, however, upheld the District Court's decision. It cited a more recent 1974 Supreme Court Grand Bench ruling that had redefined the concept of a "single act" under the Penal Code. Applying this new standard, the High Court concluded that the defendant's conduct of fleeing the scene should be evaluated as a single act.

The prosecutor appealed to the Supreme Court, setting the stage for a definitive ruling on this contentious point of law.

Understanding the Core Concepts: Ideal Competition vs. Aggravated Crimes

To appreciate the significance of this case, it is essential to understand two key concepts in Japanese criminal law regarding the plurality of crimes:

- Ideal Competition (kannenteki kyogo): This concept, outlined in Article 54, Paragraph 1 of the Penal Code, applies when a single act violates multiple criminal statutes or results in multiple harms. In such cases, the offender is punished for the most serious of the crimes committed. The underlying principle is that since the wrongful conduct itself was singular, the punishment should be consolidated. For example, if a person fires a single shot that kills two people, the two resulting homicides are treated as being in ideal competition.

- Aggravated Crimes (heigo-zai): Governed by Article 45 of the Penal Code, this applies when a person commits two or more separate and distinct crimes for which a final judgment has not yet been rendered. The punishment is calculated based on the penalties for the individual crimes, often aggregated up to a statutory maximum, leading to a more severe outcome than for ideal competition.

The central question before the Supreme Court was whether K's failure to rescue the victim and failure to report the accident constituted a "single act" (leading to ideal competition) or two "separate acts" (leading to aggravated crimes).

The Supreme Court's Majority Opinion: A Shift to Social Reality

The Grand Bench, in its majority opinion, affirmed the lower courts' decisions and ruled in favor of ideal competition. In doing so, it explicitly overturned its own 1963 precedent. The Court's reasoning was built on a specific, and at the time relatively new, definition of a "single act."

The "Single Act" Standard

The Court began by reiterating the standard established in its 1974 rulings:

"A 'single act' as stated in Article 54, Paragraph 1 of the Penal Code refers to a case where, under a naturalistic observation divorced from legal evaluations and mens rea considerations, the actor's conduct is evaluated as a single event from a social perspective."

This standard directs judges to step back from a purely legalistic analysis of the elements of each crime and instead look at the defendant's physical actions as a whole, through the lens of ordinary social understanding.

Applying the Standard to Omissions

The most critical step in the Court's logic was its declaration that this standard applies not only to positive actions (commissions) but also to failures to act (omissions). The term "conduct" or "dynamics" (dotai), the Court clarified, encompasses omissions.

Applying this framework to the case, the majority reasoned:

- The Road Traffic Act requires both the duty to render aid and the duty to report to be fulfilled "immediately" after a traffic accident.

- When a driver violates both duties by fleeing the scene, this behavior is commonly recognized in society as a single, unified social event: a "hit-and-run" (hiki-nige).

- From this social and naturalistic viewpoint, it would be unnatural to treat the failure to aid and the failure to report as two separate and distinct acts.

Therefore, the Court concluded:

"When a driver, who bears the duties under both the first and second sentences of Article 72, Paragraph 1 of the Road Traffic Act arising from a single traffic accident, has no intention of fulfilling either and leaves the scene, the omissions violating each duty should, absent special circumstances, be evaluated as a single course of conduct from a social perspective. The crimes for violating each duty are, therefore, in a relationship of ideal competition under Article 54, Paragraph 1 of the Penal Code."

This decision represented a significant jurisprudential shift. It moved the analysis away from a formalistic counting of the legal duties violated and toward a holistic assessment of the defendant's behavior as a singular social phenomenon.

The Dissenting Opinion: A Focus on the Nature of Legal Duty

A powerful dissenting opinion offered a starkly different perspective, arguing that the majority's approach was fundamentally flawed in its understanding of criminal omissions.

The dissent's core arguments were:

- The Indivisibility of Omission and Duty: An omission, in the criminal law sense, is not simply "doing nothing." It is the failure to perform a specific, legally required action. Therefore, one cannot determine the number of omissions without considering the nature and number of the legal duties imposed. The majority's attempt to analyze the "conduct" while "divorced from legal evaluations" was, in the context of omissions, a logical impossibility.

- Counting the Required Acts: The duty to render aid requires specific actions like calling an ambulance or administering first aid. The duty to report requires a different set of actions: contacting a police officer and providing specific information about the accident. Since the required acts are entirely different, the failure to perform them must constitute two separate omissions.

- The Majority's Alleged Confusion: The dissent accused the majority of confusing the defendant's positive act of "fleeing" with the criminal omissions themselves. The act of fleeing is the factual backdrop, but the crimes are the failures to perform specific duties. The majority, by focusing on the "hit-and-run" as a single event, was mistakenly treating the surrounding physical action as the criminal omission itself.

In essence, the dissent championed a more formalistic, duty-based analysis, concluding that since two distinct duties were breached, two separate crimes were committed, which should be treated as aggravated crimes.

The Concurring Opinions: Bolstering the Majority's Position

Several concurring opinions were filed to further elaborate on the majority's reasoning and counter the dissent. These opinions offered deeper theoretical justifications.

One key theme was the idea that determining the number of acts is a "pre-constitutive" inquiry. That is, the question of whether there is one act or several is a factual determination that occurs before applying the legal definitions (constituent elements, or kosei-yoken) of the crimes. The law then evaluates this singular, pre-identified factual event to see which criminal provisions it violates. The "hit-and-run" is the factual event; the law then recognizes that this one event breached two distinct duties.

Another powerful point raised in the concurring opinions related to Japan's Constitution. It was argued that interpreting the defendant's conduct as a "single act" aligns better with the spirit of Article 39 of the Constitution, which prohibits double jeopardy. While the legal issue was one of statutory interpretation, not direct constitutional law, the justices suggested that a construction of the law that avoids punishing a person twice for what the public perceives as a single wrongdoing is more consistent with fundamental principles of justice and public understanding. This approach, they argued, prevents an overly technical legal analysis from creating a result that feels unjust to the average citizen.

Significance and Legacy

The 1976 Grand Bench ruling is a landmark decision for several reasons:

- Unified Standard for Acts and Omissions: It authoritatively established that the same "naturalistic and social observation" standard applies for determining the unity of an act for both crimes of commission and crimes of omission.

- Primacy of Social Reality over Legal Formalism: The judgment prioritized the social understanding of an event ("hit-and-run") over a more rigid, formalistic counting of violated legal duties. It reflects a judicial philosophy that the application of criminal law should not be detached from common-sense social perceptions.

- Enduring Precedent: This case remains the leading authority in Japan on the plurality of crimes in hit-and-run scenarios. While the theoretical debate between the majority and dissenting views continues in academic circles, the Court's conclusion has provided a stable and clear precedent for lower courts for decades.

The case of K stands as a profound exploration of the conceptual foundations of criminal law. It illustrates the tension between viewing a crime as a breach of a formal legal norm versus viewing it as a tangible, socially understood human action. By choosing the latter, the Supreme Court of Japan opted for a more holistic and arguably more intuitive approach to justice, ensuring that the legal classification of an act remains grounded in the reality of the conduct itself.