A Landmark from 1915: When Can a Third Party Be Sued for Interfering with a Contract in Japan?

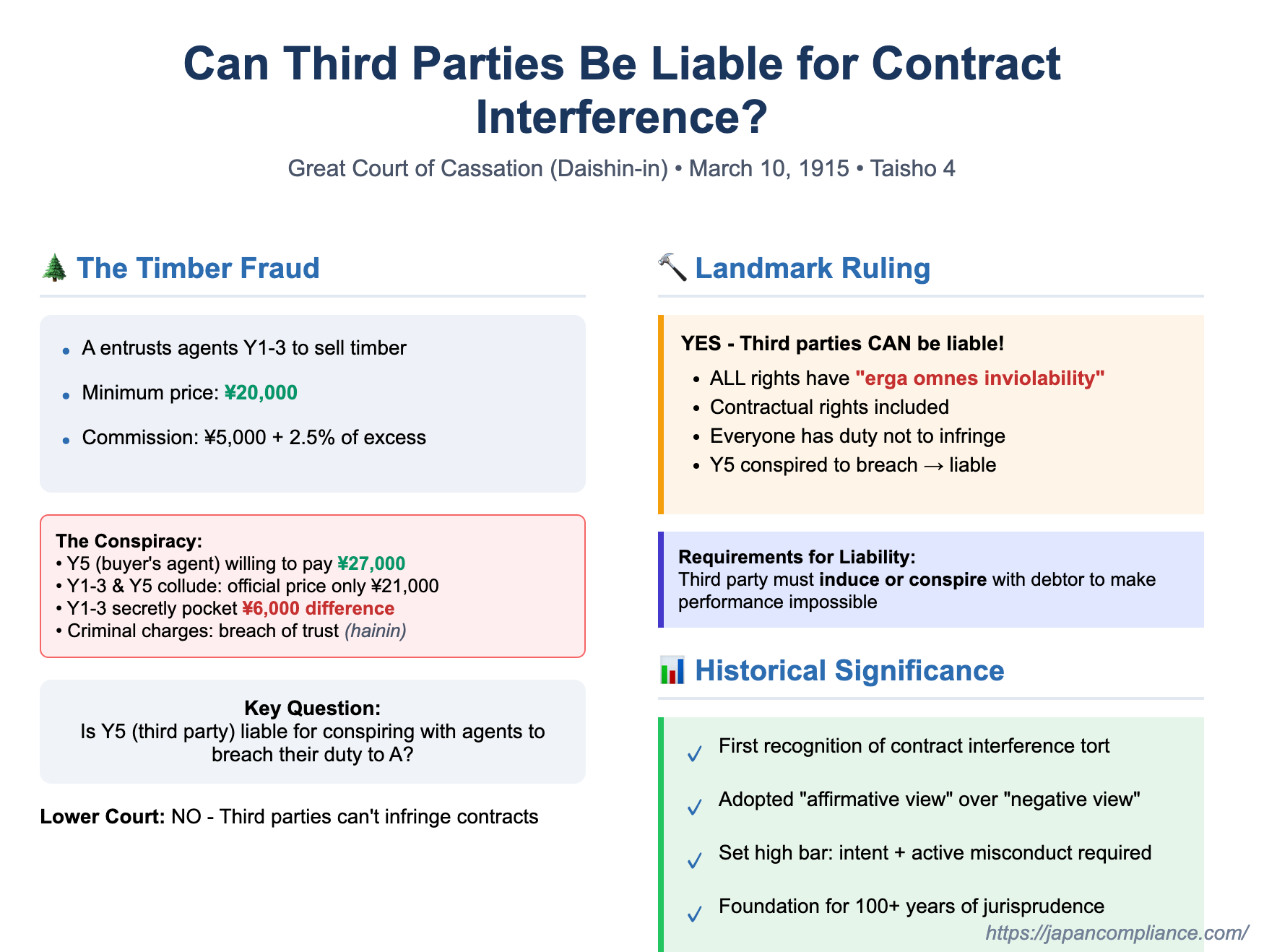

Long before modern complexities of global commerce, the Japanese judiciary grappled with a fundamental question: if a third party intentionally meddles in a contract between two other parties, causing one of them loss, can that third party be held liable for damages? The Great Court of Cassation (Daishin-in), Japan's highest court before World War II, delivered a pioneering judgment on this issue on March 10, 1915 (Taisho 4), in a case involving breach of trust and a subsequent private claim for damages. This ruling laid an early foundation for the principle of third-party liability for infringing contractual rights.

The Facts: A Breach of Trust and Collusion in an Agency Agreement

The case arose from a scheme to defraud a property owner during the sale of timber:

- The Agency Agreement: An individual, A (the victim or principal), entrusted three agents (Y1, Y2, and Y3; collectively Y1-3) with selling standing timber from A's forest. The minimum acceptable sale price was set at 20,000 yen. A promised Y1-3 a commission of 5,000 yen upon successful sale, plus an incentive: an additional 2.5% of any amount exceeding the 20,000 yen minimum, to encourage them to secure the best possible price.

- The Buyer and the Scheme: Y1-3 discovered that an individual named Y5, acting as an agent for a prospective buyer (Y4), was willing to purchase the timber for 27,000 yen. Instead of acting in A's best interest, Y1-3 decided to cause A financial loss and enrich themselves. They revealed their fraudulent intent to Y5, who agreed to participate in the plan.

- The Fraudulent Transaction: Y1-3 and Y5 colluded to set the official sale price of the timber to Y4 at only 21,000 yen. Y1-3 then secretly received the 6,000 yen difference directly from Y4 (via Y5), keeping this from A.

- Criminal and Civil Actions: Criminal proceedings were initiated against Y1-3 for breach of trust (hainin) and against Y5 for aiding and abetting this breach. Alongside these criminal charges, an individual named X (whose exact relationship to A is not specified in the provided summary but was presumably acting to recover A's losses or losses stemming therefrom) filed an "incidental private action" (futai shiso). This was a procedure under the old Meiji Code of Criminal Procedure allowing civil damages claims to be pursued within a criminal case (a procedure not available under current Japanese criminal procedure law). X sought damages from Y1-3 and, significantly, from Y5 for the harm caused by their actions.

The central legal question in X's private action against Y5 was whether Y5, by knowingly participating in Y1-3's scheme to defraud A, had unlawfully infringed A's contractual rights against Y1-3, thereby committing a tort (an unlawful act, fuhō kōi) for which Y5 would be liable to A (or X acting for A's interest).

The Legal Conundrum: Can a Third Party "Infringe" a Contractual Right?

Traditionally, contract law emphasizes "privity of contract"—the idea that a contract creates rights and obligations only between the contracting parties. Third parties are generally not bound by the contract nor can they typically sue to enforce it.

Reflecting this traditional stance, the lower court (the Tokyo Court of Appeal in the private action) had dismissed X's claim against Y5. It acknowledged the facts of Y5's involvement but reasoned that Y5 was a third party to the agency agreement between A and Y1-3. Therefore, the lower court concluded, even if Y5's actions did interfere with A's contractual rights, this interference by a third party did not constitute a tort.

The Great Court of Cassation's Landmark Decision

The Great Court of Cassation reversed the lower court's dismissal regarding Y5, establishing a significant precedent. The Court's reasoning was articulated in two main parts:

Part I: The Inviolability of All Rights, Including Contractual Rights

The Court began with a broad and emphatic statement about the nature of rights:

- A contractual right (saiken) is indeed a right to demand a specific act from a specific person (the debtor). The creditor can only make this demand upon that particular debtor; third parties are under no direct obligation to perform the contract's terms.

- However, the Court declared, all rights—whether they are family rights (like parental authority), real rights over property (bukken), or contractual rights (saiken)—possess an inherent "erga omnes effect of inviolability" (対世的効力 - taiseiteki kōryoku). This means that all rights, by their very nature, are entitled to be free from infringement by anyone in the world.

- Consequently, every person bears a general, negative obligation not to infringe upon the rights of others. The Court stressed that this characteristic of inviolability is common to all rights, and contractual rights are not an exception to this universal principle.

Part II: Conditions for Tort Liability for Third-Party Infringement

Building on this premise of general inviolability, the Court laid down the conditions under which a third party could be held liable in tort for interfering with a contractual right:

- If a third party induces the debtor or conspires with the debtor to make the performance of all or part of the contractual obligation impossible, thereby obstructing the creditor's exercise of their right and consequently causing damage to the creditor, then the creditor can claim damages from that third party based on the general principles of tortious acts (codified in Article 709 of the Civil Code).

The Court found that Y5's actions in this case—knowingly conspiring with A's agents (Y1-3) to carry out the fraudulent sale and deprive A of the full proceeds—fit this description. Y5 intentionally infringed A's contractual rights, making Y5 liable for A's losses.

The Significance and Evolution of the Principle

This 1915 judgment was a pivotal moment in Japanese law.

Adoption of the "Affirmative View" on Contractual Right Infringement:

At the time, Japanese legal scholarship was divided on whether "rights" that could be protected under tort law (Article 709) included contractual rights.

- The "negative view" held that because contractual rights are "relative" (binding only the specific debtor), they lacked the "absolute" nature or universal inviolability of rights like property rights. Thus, a third party, owing no direct duty to the creditor, couldn't technically "infringe" the contract.

- The "affirmative view" argued that contractual rights, like all rights, possessed an inherent inviolability, and third parties did have a general duty not to unlawfully interfere with them. Dr. Hozumi Chincho, a key drafter of Japan's Civil Code, had supported this view, even citing English legal precedents involving inducement of breach of contract.

The Great Court of Cassation, with this ruling (and a similar one from its civil division around the same time), decisively endorsed the affirmative view.

Strict Requirements Established:

While opening the door for such claims, the 1915 judgment also set a high bar for liability. It wasn't enough for the third party to merely know about the contract or for their actions to have simply caused a breach. The Court required active misconduct: the third party must have "induced the debtor or conspired with the debtor".

Traditional Mainstream Interpretation (Dr. Wagatsuma Sakae):

The principle laid down in 1915 was further developed and systemized by influential scholars like Dr. Wagatsuma Sakae. His traditional mainstream view, which shaped Japanese legal thought for decades, generally accepted third-party liability but elaborated on the conditions:

- Types of Infringement: He distinguished between infringement of the creditor's status (e.g., a third party wrongfully receiving payment meant for the creditor) and infringement of the contractual performance itself.

- Heightened Illegality: For infringement of performance, especially where the debtor is induced to breach (as in the 1915 case), the third party's act must be seen as particularly wrongful or illegal. This is because contractual rights, being mediated by the debtor's will, are considered inherently "weaker" or less absolute than property rights.

- Intent Requirement: The third party generally needed to have acted with intent (koi), not just negligence. Furthermore, this intent often needed to rise to the level of actively inducing the breach or colluding with the debtor, not merely knowing about the contract and the potential for its breach.

- Objective Factors: The assessment also had to consider whether the third party was, for example, legitimately exercising their own rights (e.g., competing in business, which might incidentally affect another's contracts).

Modern Scholarly Perspectives (e.g., Prof. Kunihiko Yoshida):

More recent scholarship, such as that by Professor Kunihiko Yoshida, has revisited these traditional, strict requirements. Based on comparative law studies (particularly English law, which has a well-developed doctrine of inducing breach of contract) and a typological analysis of Japanese case law, some scholars now advocate for a more nuanced approach. They suggest that the requirements for third-party liability might be relaxed in certain categories of cases to provide more robust protection for contractual relationships against external interference. This might involve differentiating requirements based on the type of contract, the nature of the interference, and the mental state of the third party (e.g., distinguishing between bad faith knowledge and malicious intent).

Application to the Agency Scenario in the 1915 Case

In the specific facts of the 1915 case, the Great Court of Cassation found Y5 clearly liable under its newly articulated rule. Y5 was fully aware of the agency agreement between A and Y1-3 and actively conspired with Y1-3 to structure the timber sale in a way that breached Y1-3's duties to A and diverted funds from A.

The commentary accompanying the case text notes an interesting parallel between Y5's conduct and modern concepts of a third party's involvement in an agent's conflict of interest or abuse of agency authority. Under current Civil Code provisions (e.g., Articles 107 and 108), if an agent acts in conflict of interest or abuses their authority, the transaction might be treated as one of unauthorized agency, allowing the principal (A) to avoid it if the third party (like Y5 or Y4) knew or should have known of the agent's improper conduct. The commentary raises a question: in such agency-related infringements, is the high bar of "inducement or conspiracy" always necessary for third-party tort liability, or might a lesser degree of culpability (like knowledge or negligence regarding the agent's breach) suffice? Given the conspiracy in the 1915 case, this nuance wasn't critical to the outcome, but it highlights an area of ongoing legal thought.

Conclusion: A Foundational Stone for Protecting Contractual Claims

The Great Court of Cassation's decision of March 10, 1915, stands as a seminal ruling in the history of Japanese civil law. It courageously established over a century ago that the sphere of contractual relations is not entirely closed off from the law of torts and that third parties who intentionally and wrongfully interfere with these relations can be held accountable for the ensuing damage. While the core principle of potential third-party liability for contract infringement is now well-accepted, the precise conditions—particularly the nature of the third party's actions and their state of mind—have been, and continue to be, the subject of rich legal scholarship and judicial refinement in Japan. This early case remains a vital reference point in understanding the protection afforded to contractual rights against the actions of outsiders.