A Governor's Tab: Japan's Supreme Court on Disclosing Entertainment Expenses and Balancing Transparency with Official Functions

Judgment Date: January 27, 1994

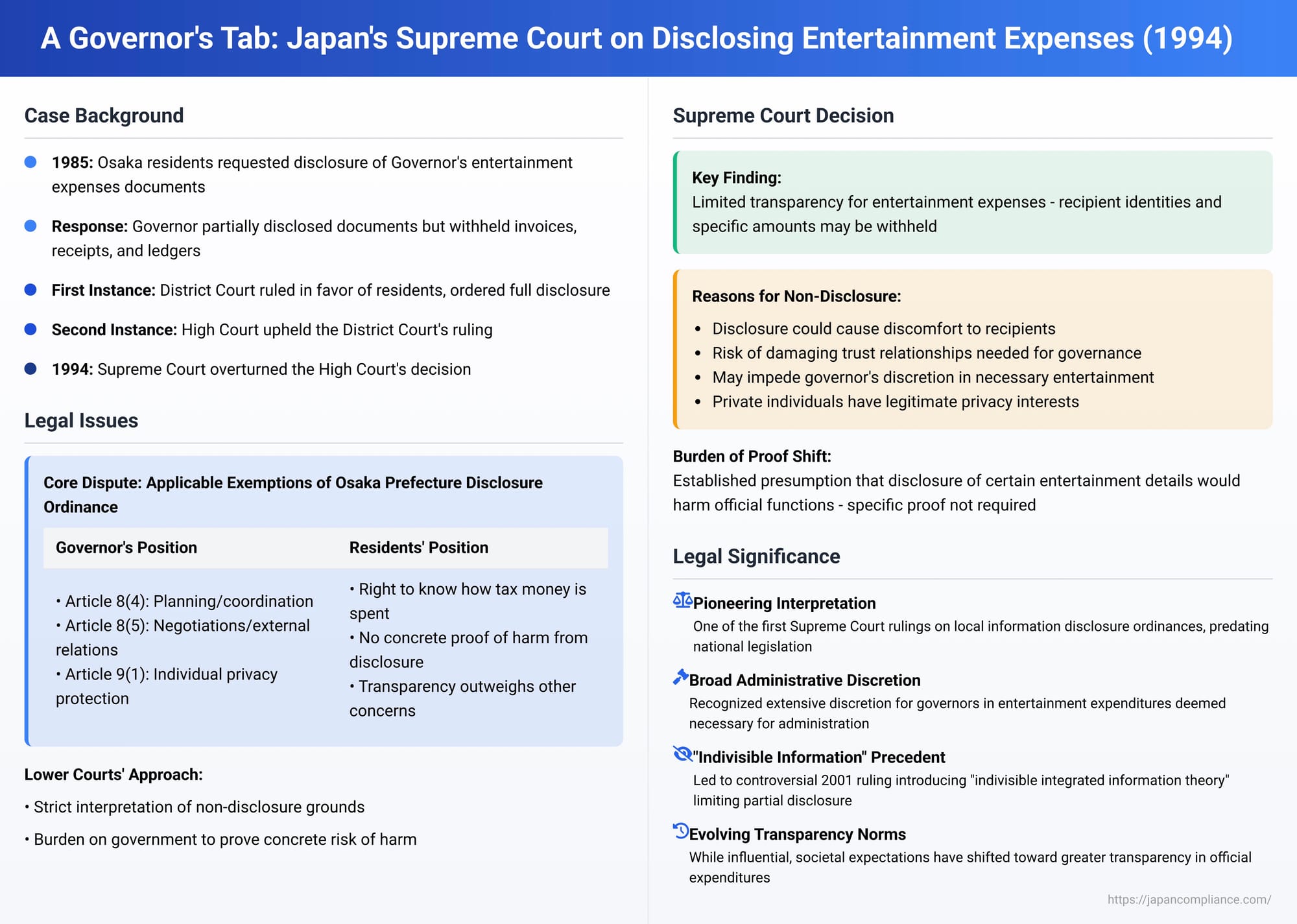

The public's right to access information about how taxpayer money is spent is a fundamental aspect of transparent and accountable governance. However, this right often intersects with the perceived need for public officials to conduct certain affairs with a degree of discretion, particularly when it involves fostering relationships or gathering information. Entertainment expenses incurred by public officials, often a subject of public scrutiny, lie squarely at this intersection. A significant Japanese Supreme Court decision from January 27, 1994 (Heisei 3 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 18), addressed this very issue, interpreting a local government's information disclosure ordinance in the context of a request for details about the Osaka Governor's entertainment expenditures. This ruling, one of the earliest by the Supreme Court on such local ordinances, predated Japan's national Act on Access to Information Held by Administrative Organs and provided crucial, albeit controversial, guidance on this sensitive matter.

The Osaka Disclosure Dispute: A Request for an Accounting

A group of residents of Osaka Prefecture, X et al. (the plaintiffs), invoked the Osaka Prefecture Public Document Disclosure Ordinance (Showa 59 Osaka Pref. Ordinance No. 2, hereinafter "the Ordinance") to request access to public documents concerning entertainment expenses (kōsaihi - 交際費) disbursed by the Governor of Osaka Prefecture, Y (the defendant). The request specifically covered the period from January to March 1985.

In response, Governor Y disclosed some of the requested documents but decided to withhold others. The withheld documents included creditors' invoices and receipts, the cash disbursement ledger for expenditures, and expenditure certifications. The Governor justified this non-disclosure by asserting that the information contained therein fell under several non-disclosure provisions of the Ordinance:

- Article 8, item 1: Protecting the legitimate interests, such as the competitive position, of business operators.

- Article 8, item 4: Protecting information related to planning, coordination, etc., conducted by prefectural agencies, the disclosure of which would risk significantly hindering the fair and proper execution of such or similar affairs.

- Article 8, item 5: Protecting information related to negotiations, external relations, litigation, etc., conducted by prefectural agencies, the disclosure of which would risk rendering the objective of such or similar affairs unachievable or significantly hindering their fair and proper execution.

- Article 9, item 1: Protecting information concerning an individual's private affairs (excluding information related to an individual's business activities) that identifies a specific individual and that it is recognized as legitimate for the individual to wish not to be generally known to others. This is essentially a privacy protection clause.

X et al. subsequently filed a lawsuit seeking the cancellation of this non-disclosure decision (referred to as "the disposition" in the case). The Osaka District Court, as the court of first instance, ruled entirely in favor of X et al., finding that none of the cited non-disclosure provisions applied and that the Governor's decision to withhold the documents was illegal. The Osaka High Court, on appeal, affirmed the District Court's ruling, dismissing Governor Y's appeal. Consequently, Governor Y appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Turn: Redrawing the Lines of Disclosure (January 27, 1994)

The Supreme Court, First Petty Bench, overturned the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings. While the Supreme Court agreed with the lower courts that the exemption for protecting business operators' interests (Article 8, item 1) did not apply to the information in question, it disagreed with their conclusions regarding the applicability of the exemptions related to the prefecture's planning/coordination and negotiation affairs (Article 8, items 4 and 5) and the privacy protection clause (Article 9, item 1).

Understanding the Governor's Role and Entertainment

The Court began by defining the nature of a governor's entertainment activities within the framework of the Ordinance's exemptions. It opined that:

- Discussions or meetings (kondan - 懇談) undertaken by the governor could fall under Article 8, item 4 (planning and coordination affairs) or Article 8, item 5 (negotiation and external relations affairs).

- Other courtesies, such as celebratory or condolence payments (keichōtō - 慶弔等), would typically fall under Article 8, item 5, as part of negotiation or external relations affairs.

Why Some Details Can Remain Private (Exemptions Applied)

The Supreme Court then elaborated on why disclosure of certain information related to these activities could be restricted.

1. Hindrance to the Proper Execution of Official Duties (Article 8, items 4 and 5):

The Court reasoned that the primary purpose of a governor's entertainment activities is to maintain and promote relationships of trust and friendship with the other party involved. If documents identifying the other party were disclosed—unless the public disclosure of their name and involvement was inherently expected from the nature of the event—several negative consequences could arise:

- For discussions or meetings, the other party might feel discomfort or distrust, potentially leading them to avoid similar official engagements with the prefecture in the future.

- The Court noted that the necessity and specifics of entertainment expenditures are generally determined on a case-by-case basis, taking into account the prefecture's particular relationship with the individual or entity involved. Public disclosure of such details could easily lead to dissatisfaction or resentment among those who were not similarly treated or who disapproved of the expenditure, regardless of its legitimacy.

- Such reactions could damage the trust and friendly relations essential for the governor's functions, thereby undermining the very purpose of the entertainment and potentially making it impossible to achieve the objectives of these official interactions.

- Furthermore, the Court considered the impact on the governor's decision-making. If the recipients and details of entertainment expenses were to be routinely disclosed, the governor might, out of concern for the aforementioned negative reactions, feel compelled to refrain from making necessary entertainment expenditures or to standardize such expenditures in a way that might not be appropriate for the specific circumstances. This could significantly impede the governor's ability to properly conduct entertainment-related official duties.

Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that documents through which the recipient of the governor's entertainment can be identified are generally eligible for non-disclosure under Article 8, item 4 or 5 (for discussions/meetings) or Article 8, item 5 (for other courtesies like celebratory/condolence payments). An exception would be cases where the public disclosure of the recipient's name and involvement was expected from the outset (e.g., publicly announced events or attendees) or where such disclosure would not pose the risks outlined by the Court.

2. Protection of Personal Privacy (Article 9, item 1):

The Court also found that information pertaining to private individuals who were recipients of the governor's entertainment qualified for non-disclosure under the privacy protection clause.

- It stated that even if the entertainment is part of the governor's official duties, for the private individual involved, the interaction constitutes a private event or occurrence.

- The Supreme Court asserted that private individuals who interact with the governor in such contexts—whether for discussions or as recipients of celebratory/condolence payments—would generally wish for the specific costs and amounts involved not to be known to others. The Court deemed this desire to be legitimate.

- Consequently, such information regarding interactions with private individuals, unless its public disclosure was inherently expected due to the nature or content of the engagement, should be considered to fall under the protection of Article 9, item 1.

Thus, the Court ruled that documents pertaining to private individuals, if they allow for the identification of the individual, should, as a general rule, be withheld under this privacy provision.

3. No Exemption for Business Interests (Article 8, item 1):

On a concurring note with the lower courts, the Supreme Court did affirm that the information contained in creditors' invoices and receipts (e.g., from restaurants) did not fall under the exemption protecting business operators' commercial interests (Article 8, item 1).

The Rationale Deconstructed: Key Legal Principles & Commentary Insights

This 1994 Supreme Court judgment was a significant early interpretation of local information disclosure ordinances and carried several implications, as highlighted in legal commentary.

- Broad Discretion for Governors: The ruling recognized extensive discretion for governors in making entertainment expenditures deemed necessary for the smooth operation of prefectural administration, emphasizing that the necessity and details of such expenses are determined on an individual basis. The case focused not on the legitimacy of entertainment expenses per se, but on how their disclosure should be controlled.

- The "Right to Know" Sidestepped: The Osaka Prefecture Public Document Disclosure Ordinance, in its preamble, explicitly mentioned the guarantee of the "right to know". The lower courts had interpreted the ordinance through this lens, viewing it as a means to actualize this right. The Supreme Court, however, did not delve into the relationship between the "right to know" as a concept and the specific right to request information disclosure under the ordinance. Instead, it treated the case primarily as a matter of statutory interpretation of the ordinance's provisions.

- The Burden of Proof Shift: A critical aspect of the Supreme Court's decision was its approach to the burden of proof regarding non-disclosure justifications. The District Court had strictly interpreted the non-disclosure grounds, essentially requiring the government to objectively demonstrate a concrete risk of harm from disclosure and to weigh this against the public benefit of disclosure. The High Court, while not adopting the District Court's exact criteria, maintained that the implementing agency (Governor Y) bore the burden of proving that non-disclosure grounds existed, and found that the Governor had failed to prove any resulting hindrance to official duties or that the information was something individuals would wish to keep private.

The Supreme Court diverged significantly on this point. For information that could identify the recipient of the governor's entertainment, the Court established a general presumption that disclosure would risk causing discomfort, damaging relationships, and hindering the governor's ability to exercise discretion and properly conduct entertainment-related duties. This meant that Governor Y was not required to provide specific, document-by-document proof of such harm for these categories of information. This approach contrasted with another Supreme Court decision around the same time (the Osaka Prefecture Water Department entertainment expenses case), which required the administrative agency to provide specific proof regarding the confidential nature of meetings and the other party's awareness of that confidentiality. The differing outcomes are attributed to the perceived difference in nature between the governor's high-level entertainment expenses and those incurred by a specific department. - The Shadow of In Camera Review (or Lack Thereof): Legal commentary suggests that the Supreme Court's stance on not requiring specific proof of harm from the agency in this case might have been influenced by the practicalities of Japan's adversarial litigation system, which at the time lacked a robust mechanism for in camera (private, by the judge only) inspection of the documents in question. Without such a mechanism, forcing an agency to fully substantiate its claims of harm in open court could effectively lead to the disclosure of the very information it seeks to protect if it fails to meet the evidentiary burden. The need for in camera review in information disclosure lawsuits has been a recurring point of discussion in Japan. An attempt to introduce it through a proposed amendment to the national Information Disclosure Act in 2011 ultimately failed as the bill was scrapped.

- Defining "Personal Information" in Context: The Supreme Court's determination that details of the governor's entertainment involving private individuals constituted protected personal information was heavily influenced by the specific wording of Article 9, item 1 of the Osaka ordinance. This provision protected information "that it is recognized as legitimate for the individual to wish not to be generally known to others". The Court found that individuals indeed have a legitimate desire for the financial specifics of such interactions to remain private.

The Aftermath and Evolving Norms

The 1994 Supreme Court decision was not the final word on this particular dispute. The case was remanded to the Osaka High Court, which, in 1996, applied the Supreme Court's criteria and ordered some information to be fully disclosed, while other information was to be disclosed only partially (e.g., with the recipient's name redacted).

This, in turn, led to another appeal. In a subsequent ruling in 2001 concerning the remanded case, the Supreme Court largely sided with the Governor, holding that the names of recipients of governor's entertainment expenses are generally non-disclosable. More controversially, this 2001 decision introduced what is known as the "indivisible integrated information theory" (dokuritsu ittai setsu or jōhō tan'i ron). This theory posits that if a portion of information qualifying for non-disclosure is part of an "indivisible integrated piece of information" (such as the part of a document that identifies a recipient), the implementing agency has no obligation to further break down or redact that piece to disclose the remainder. This raised significant concerns, as it could imply that if a document contains any personally identifiable information, the agency might not be required to black out that information and disclose the rest, potentially undermining the principle of partial disclosure generally favored in information access regimes.

It is important to note that since these early rulings, societal norms and expectations regarding the transparency of official expenditures have evolved considerably in Japan. Many local governments now proactively establish clear standards for entertainment expenses and disclose them widely to enhance transparency and public trust.

Legacy of the 1994 Ruling

The 1994 Supreme Court judgment on the Osaka Governor's entertainment expenses was a product of its time, an era when local governments were at the forefront of establishing information disclosure systems in Japan, often well ahead of national legislation. The ruling attempted to provide general standards for disclosure in this sensitive area, taking into account administrative practices of the day.

While its direct precedential value for interpreting specific, often revised, local ordinances may have diminished over time, the 1994 decision remains significant for several reasons:

- It was one of the first Supreme Court pronouncements on local government information disclosure, highlighting key legal and practical issues in the interpretation and application of these pioneering ordinances.

- It framed the ongoing debate on how to balance public access, administrative efficiency, the protection of official functions, and individual privacy in the specific context of official entertainment expenses.

- Given that, unlike personal information protection laws (which have seen moves towards national standardization), local information disclosure ordinances continue to be interpreted and applied by individual local governments, foundational Supreme Court decisions like this one retain a degree of relevance for understanding the judicial approach to such matters.

Conclusion

The 1994 Supreme Court decision concerning the Osaka Governor's entertainment expenses was a key early judicial attempt to navigate the complex terrain between the public's demand for transparency and the government's arguments for confidentiality in conducting its affairs. By generally shielding the identities of individuals entertained by the governor and specific financial details from public disclosure, citing potential harm to official duties and legitimate privacy concerns, the Court set a relatively high bar for access to such information under the then-existing local ordinance. While societal expectations and legal frameworks have continued to evolve, this ruling remains a significant reference point in the history of information disclosure law in Japan.