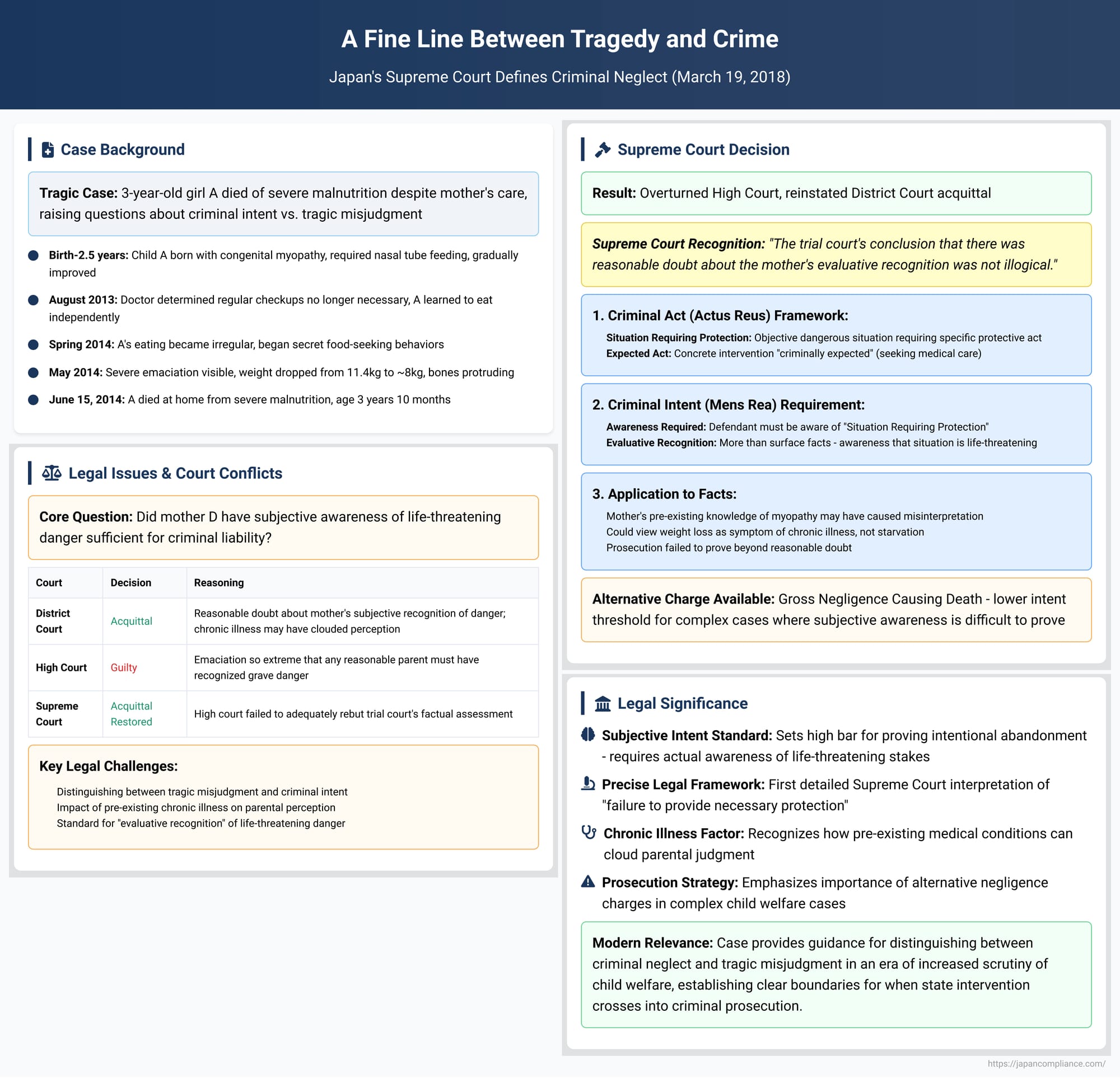

A Fine Line Between Tragedy and Crime: Japan's Supreme Court Defines Criminal Neglect

Case Title: Case of Abandonment by a Person Responsible for Protection Causing Death (Alternative Count: Gross Negligence Causing Death)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Decision Date: March 19, 2018

Introduction

Cases of fatal child neglect are among the most difficult and heart-wrenching in any legal system. They force courts to confront a painful question: where does tragic parental misjudgment end and criminal liability begin? Is a parent who fails to recognize the severity of their child's deteriorating health guilty of homicide? This question lies at the heart of the Japanese crime of "Abandonment by a Person Responsible for Protection" (保護責任者遺棄罪, hogo sekininsha iki zai), particularly its variant involving a "failure to provide necessary protection" (不保護, fuhogo).

In a landmark decision in 2018, the Supreme Court of Japan provided its most detailed interpretation of this crime. The case involved a young mother whose chronically ill child died of malnutrition. In a rare move, the Court overturned a high court's conviction and reinstated the trial court's acquittal, not because it condoned the outcome, but because it found the prosecution had not proven a critical element: the mother's subjective awareness of the life-threatening danger. The ruling precisely defines the act and, crucially, the intent required to prove this grave offense.

The Facts: A Fragile Life and a Fatal Decline

The case centered on a three-year-old girl, A, and her mother, the defendant, D. The child's life was challenging from the start.

- A Chronic Illness: A was born with congenital myopathy, a disease that caused weak muscles and delayed physical development. From birth, she required medical intervention for feeding, including the use of a nasal tube.

- A Period of Stability: By the age of two and a half, A's condition improved. She learned to eat on her own, and in August 2013, her doctor determined that regular checkups were no longer necessary.

- A Troubling Decline: A's eating habits remained irregular; she would sometimes go a full day without eating. In the spring of 2014, she began exhibiting unusual food-seeking behaviors, such as secretly eating rice from the rice cooker outside of mealtimes. Her physical appearance deteriorated dramatically. A video taken in May 2014 showed her to be severely emaciated compared to photos from just seven months earlier, with the bones of her legs and knees visibly protruding. While her height had increased, her body weight had plummeted from 11.4 kg (25.1 lbs) to approximately 8 kg (17.6 lbs).

- The Tragic Outcome: The defendant was aware of her daughter's eating patterns and her increasingly thin physique. Despite this, she did not take A to see a doctor after late February 2014. On June 15, 2014, at the age of three years and ten months, A died at home from severe emaciation caused by malnutrition.

A Judicial Tug-of-War: Guilty or Not Guilty?

The mother, D, was charged with abandonment by a person responsible for protection causing death. The path through the courts revealed a deep disagreement about how to assess her culpability.

- The District Court's Acquittal: The trial court in Osaka found the mother not guilty. The judges acknowledged the child's objectively terrible condition but concluded there was reasonable doubt as to whether the mother subjectively recognized the situation as life-threatening. They reasoned that her knowledge of A's underlying myopathy, which made her naturally thin, could have led her to misinterpret the severity of the weight loss. They also noted that other relatives and friends had seen the child during this period and none had raised an alarm to the parents about her health, which could have reinforced the mother's misperception.

- The High Court's Reversal: The Osaka High Court overturned the acquittal. It found the trial court's reasoning to be flawed, arguing that the child's emaciation was so objectively extreme that any reasonable parent, especially the mother who bathed her, must have recognized the grave danger. It remanded the case for a new trial.

The Supreme Court's Definitive Framework for "Failure to Protect"

The mother appealed, and the Supreme Court took the opportunity not only to decide her fate but to clarify the law for the entire nation. It overturned the High Court and reinstated the acquittal, establishing a clear two-part framework for the crime of "failure to protect."

1. Defining the Criminal Act (Actus Reus)

The Court first defined the criminal act of "failure to protect." It is not a general failure of parenting but a highly specific omission. The act consists of two components:

- A "Situation Requiring Protection" (yō-hogo jōkyō): There must be an objective, dangerous situation in which the victim requires a specific protective act for their survival. This makes the victim's need for help a formal prerequisite of the crime. In this case, the Court identified this situation as the child's state of "severe malnutrition," which was evident by at least late May 2014.

- Failure to Perform an "Expected" Act: The defendant must have failed to perform a specific action that is "criminally expected" of a person in their position. This is not about failing to provide general care but about the omission of a concrete, necessary intervention. Here, the expected act was for the parents to seek a doctor's advice on nutrition or to get the child medical treatment for her severe malnutrition.

2. Defining the Criminal Intent (Mens Rea)

This was the most critical part of the ruling. The Court held that the defendant's intent must correspond directly to the elements of the criminal act. To be guilty, the defendant must have been aware of the "Situation Requiring Protection."

The Court’s analysis suggests this requires more than just recognizing the surface-level facts (e.g., "my child is very thin"). It requires a deeper, evaluative recognition: an awareness that the situation is life-threatening and that the specific protective act (like seeking medical care) is necessary for survival.

This is precisely where the prosecution's case failed. The Supreme Court found that the trial court's conclusion—that there was reasonable doubt about the mother's evaluative recognition—was not illogical. The trial court had plausibly reasoned that the mother's pre-existing knowledge of her daughter's chronic illness may have caused her to tragically misinterpret the severity of the weight loss, viewing it as a symptom of the myopathy rather than life-threatening starvation. The Supreme Court ruled that the High Court had not provided a sufficiently compelling basis to overturn this detailed factual assessment made by the trial judges.

Implications and the Role of Negligence

The Supreme Court's decision sets a high bar for proving intentional abandonment by failure to protect. It underscores that a conviction requires prosecutors to prove, beyond a reasonable doubt, the defendant's subjective state of mind—their actual awareness of the life-or-death stakes. This can be exceedingly difficult in complex cases where a child suffers from a chronic illness, and a parent's perception may be clouded by a history of managing that illness.

This does not, however, mean that such conduct is without legal consequence. The commentary notes the importance of an alternative charge: Gross Negligence Causing Death (jū-kashitsu chishi). Even if the mother did not intentionally allow her child to die (lacking the required subjective recognition of the danger), a prosecutor could still argue that she had a duty of care to recognize the danger and that her failure to do so was grossly negligent. In such complex cases, prosecutors are likely to include this as a secondary charge to ensure that even if the high bar for intent cannot be met, accountability for a death caused by severe neglect can still be achieved.

Conclusion

The 2018 Supreme Court decision is a masterclass in legal precision. It does not excuse fatal neglect but carefully defines the crime of intentional homicide by omission. The ruling clarifies that the offense requires a specific, life-threatening situation and the failure to perform a concrete, expected act of rescue. Most importantly, it establishes that a conviction hinges on proving the caretaker's subjective awareness of the mortal danger. The case stands as a powerful illustration of the profound challenge of judging a person's state of mind, drawing a fine but critical legal line between tragic misjudgment, criminal negligence, and the deliberate intent required for murder by inaction.