A Father's Right, A Child's Status: Transgender Parentage and Japan's Presumption of Legitimacy

Judgment Date: December 10, 2013 (Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench)

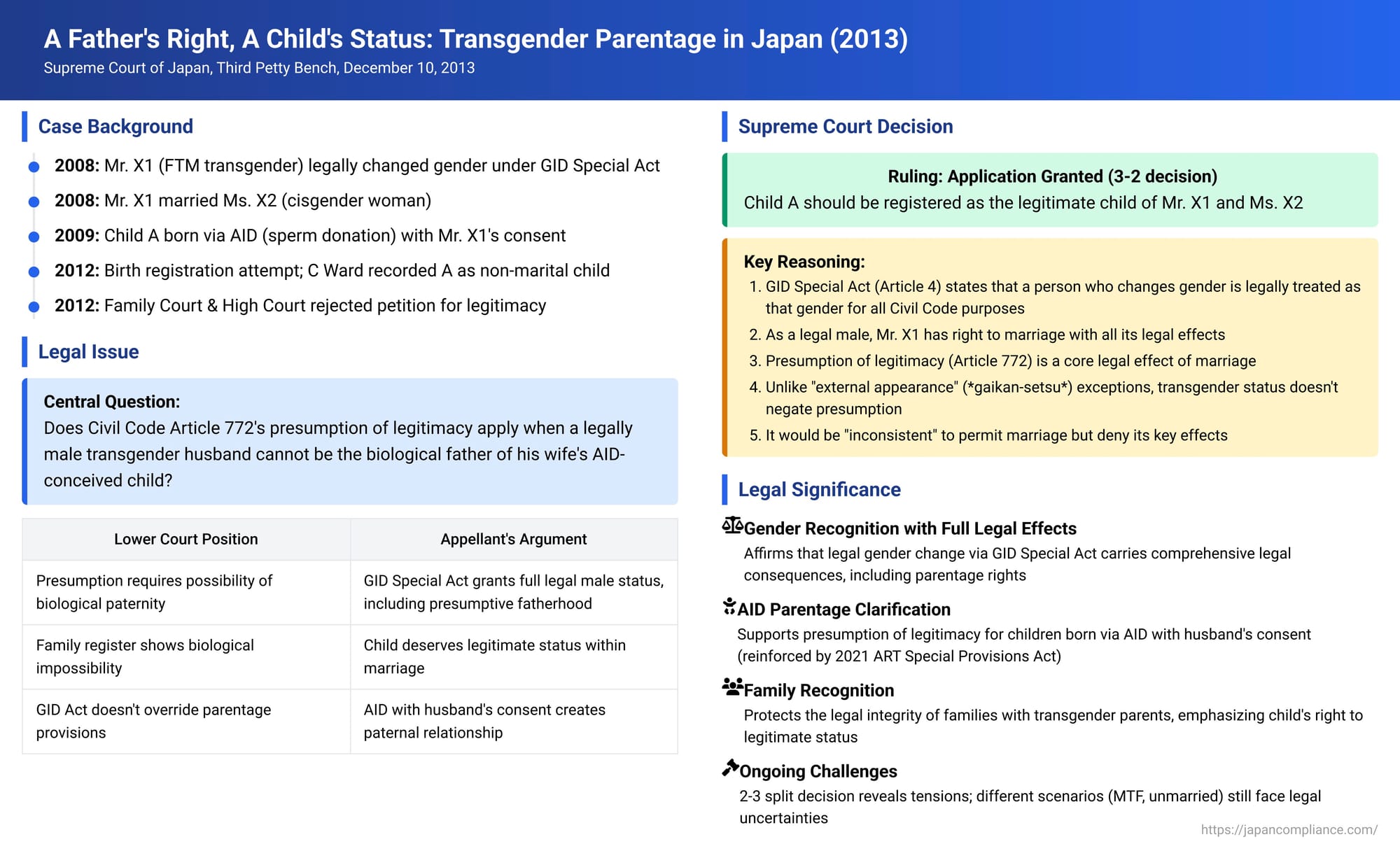

In a landmark 2013 decision, Japan's Supreme Court addressed a deeply personal and legally intricate question: does the legal presumption that a child born to a married woman is the child of her husband apply when the husband is a transgender man who cannot be the biological father, and the child was conceived via sperm donation? The Court's affirmative answer was a significant step in recognizing the parental rights of transgender individuals within marriage, while also highlighting the evolving interplay between traditional family law principles and modern medical and social realities.

The Journey to Parenthood: A Transgender Man, His Wife, and AID

The case involved Mr. X1, who was born female but was diagnosed with Gender Identity Disorder (GID). In 2008, Mr. X1 underwent a legal gender change to male, a process recognized under Japan's "Act on Special Cases Concerning the Handling of Gender for Persons with Gender Identity Disorder" (commonly referred to as the GID Special Act). Later that same year, Mr. X1 married Ms. X2, a woman.

The couple wished to have a child. With Mr. X1's consent, Ms. X2 conceived their child, A, through Artificial Insemination by Donor (AID), using sperm from an anonymous male donor. Ms. X2 gave birth to A in 2009.

Following A's birth, Mr. X1 attempted to register A as their legitimate child. Initially, he submitted a birth notification to the mayor of B City, but this was not accepted, reportedly due to deficiencies in the documentation. After withdrawing this notification and changing the family's registered domicile to C Ward, Mr. X1 submitted a new birth notification in 2012 to the mayor of C Ward, again seeking to register A as the legitimate child of himself and Ms. X2.

The C Ward mayor, however, raised concerns about the parentage details, particularly Mr. X1's status as the father. When Mr. X1 did not provide further clarification as requested, the ward office registered A with the father's column on the family register (koseki) left blank, effectively listing A as Ms. X2's non-marital child.

In response, Mr. X1 and Ms. X2 petitioned the Tokyo Family Court in March 2012, seeking a court order to correct A's family register entry to reflect A as their legitimate child, born to Mr. X1 as the father and Ms. X2 as the mother, in accordance with Article 113 of the Family Register Act.

The Legal Standoff: Lower Courts Deny Legitimacy

The path through the lower courts proved challenging for the couple:

- Tokyo Family Court (October 31, 2012): Dismissed the petition.

- Tokyo High Court (December 26, 2012): Also dismissed their appeal. The High Court reasoned that the legal presumption of legitimacy for a child born during marriage (found in Article 772 of the Japanese Civil Code) is fundamentally based on the possibility of a physiological blood relationship between the husband and child, within the context of marriage. The High Court stated that if the family register itself (which would indirectly note Mr. X1's gender transition [cite: 2]) makes it clear that no such biological tie can exist, then the very premise for applying Article 772 is absent. It further held that the GID Special Act, while changing legal gender, does not alter the fundamental application of Civil Code provisions regarding parentage, especially since one of the conditions for legal gender change under the GID Special Act is that the individual no longer has reproductive glands or that their function is permanently lost.

Mr. X1 and Ms. X2 then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Presumption of Legitimacy Applies

In a significant ruling, the Supreme Court overturned the decisions of the lower courts and granted the couple's petition to correct the family register, thereby recognizing A as the legitimate child of Mr. X1 and Ms. X2.

The majority opinion of the Supreme Court reasoned as follows:

- Effect of the GID Special Act: Article 4, Paragraph 1 of the GID Special Act explicitly states that a person whose legal gender has been changed is, for the application of the Civil Code and other laws, deemed to have changed to that other gender, unless a specific law provides otherwise.

- Marriage and Its Consequences: Therefore, Mr. X1, having legally become male, is considered male for all legal purposes. This not only allows him to marry a woman as her husband under the Civil Code but also means that the standard legal effects of marriage apply to him.

- Presumption of Legitimacy as a Key Marital Effect: A major legal effect of marriage is the presumption under Civil Code Article 772 that a child conceived by the wife during the marriage is the husband's child.

- Distinguishing from Gaikan-Setsu (External Appearance Doctrine): The Court acknowledged its own precedents where this presumption of legitimacy does not apply. These are typically cases where, during the likely period of conception, the couple was already factually divorced, living far apart with no contact, or other circumstances made it clear there was no opportunity for sexual relations that could have led to conception (this is often referred to as the "external appearance" or gaikan-setsu doctrine).

- Inconsistency in Denying Presumption: However, the Court found that the situation of a transgender man who cannot biologically father a child is different. It reasoned that it would be "inconsistent" and "not appropriate" for the law to permit such an individual to marry as a man, yet then deny the application of Article 772—one of the primary effects of that marriage—simply because the child could not have been conceived through sexual relations with him. The legal recognition of his male status for marriage purposes should extend to the consequences of that marriage concerning children.

- Application to the Case: Since A was conceived by Ms. X2 during her marriage to Mr. X1, A is presumed to be Mr. X1's child under Article 772. There were no overriding circumstances, such as factual divorce, that would negate this presumption under the gaikan-setsu doctrine. Therefore, the family registrar's act of leaving the father's column blank on A's family register, based on the reasoning that Mr. X1's gender transition meant A could not be his biological child and thus was not presumed legitimate, was legally impermissible. The family register should be corrected to list Mr. X1 as A's father.

The decision was accompanied by two concurring supplementary opinions (from Justices Terada Itsuro and Kiuchi Michiyoshi, who agreed with the outcome but wished to add further reasoning) and two dissenting opinions (from Justices Okabe Kiyoko and Otani Takehiko), highlighting the complexity and contentious nature of the legal issues involved. For instance, Justice Terada's supplementary opinion emphasized that if the law goes to the extent of allowing marriage for individuals who cannot biologically procreate within that specific gender role, it should not then deny them the possibility of having legitimate children on the grounds of a lack of biological connection. [cite: 1]

The GID Special Act: Reshaping Legal Gender and Its Consequences

The "Act on Special Cases Concerning the Handling of Gender for Persons with Gender Identity Disorder" is central to this case. It allows individuals diagnosed with GID to petition a family court to legally change their gender. Once this change is approved, Article 4(1) of the Act dictates that the person is treated as their new legal gender for the application of the Civil Code and other laws, unless a specific law states otherwise. This provision was key to the Supreme Court's reasoning that Mr. X1, as a legal male, could marry Ms. X2 as her husband, and that the standard legal incidents of marriage, including the presumption of legitimacy, should follow. [cite: 1]

Before this Supreme Court decision, there was uncertainty in practice. While some medical bodies initially permitted AID for such legally married couples, rejections of legitimate birth registrations by Koseki offices led to confusion. A 2011 inquiry by the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology to the Ministry of Justice resulted in a response that such children could not be registered as legitimate or acknowledged by the transgender father, though special adoption was possible. [cite: 2] This Supreme Court ruling provided crucial clarification directly opposing that administrative guidance.

Reconciling Biological Inability with Legal Presumption

The core tension in this case lies in the fact that Mr. X1, due to his biological origins as female and the requirements of the GID Special Act (which include lack of reproductive gland function for the original sex [cite: 2]), could not be the biological father of A.

- The Majority View: The Supreme Court's majority effectively prioritized the legal status conferred by the GID Special Act and the institution of marriage over the biological impossibility. By allowing Mr. X1 to marry as a man, the law accepts him in that role, and the presumption of legitimacy flows as a consequence of that marital status. His inability to father a child through intercourse was deemed distinct from the gaikan-setsu situations, which typically involve a breakdown of the marital relationship or physical separation making conception by the husband impossible.

- The Dissenting View: The dissenting opinions, in contrast, emphasized the biological reality. Justice Okabe, for example, argued that because Mr. X1's inability to biologically father a child as a male was a clear consequence of his gender change (a fact ascertainable from the legal process itself), the conditions for applying the presumption of legitimacy were absent, similar to how the gaikan-setsu doctrine operates when marital relations are impossible. [cite: 1] Some commentators also suggested that the GID Special Act's silence on parentage matters was a legislative oversight, and interpretation should therefore prevent the automatic application of the presumption. [cite: 3]

The Role of AID and Evolving ART Law

This case also had implications for children born via Artificial Insemination by Donor (AID) within a marriage, a topic that, at the time of the 2013 decision, lacked specific comprehensive legislation in Japan. Some legal commentators viewed the Supreme Court's decision as profoundly significant for affirming that children born via AID to a married woman are, in general, presumed to be the legitimate children of her husband under Article 772. [cite: 3]

Since this ruling, Japan has enacted the "Act on Special Provisions of the Civil Code Concerning Parent-Child Relationships with Children Born Through Assisted Reproductive Technology," which came into effect in 2021. Article 10 of this new ART Act stipulates that a husband who has consented to his wife undergoing assisted reproduction using donated sperm cannot later file a suit to deny the legitimacy of the child born as a result. This new legislation would likely reinforce the legal fatherhood established in cases like Mr. X1's, where consent to AID was present. Had the Supreme Court's dissenters prevailed (meaning Article 772 did not apply), then Article 10 of the ART Act might also not apply, leaving the child's status less certain.

Broader Implications for Transgender Parents

The GID Special Act has several conditions for legal gender change, including that the person must not have any minor children and must lack reproductive glands or have their function permanently lost. [cite: 3] If a parent legally changes gender when their children are already adults, their existing parental status (e.g., "father" or "mother" to those adult children) is maintained. [cite: 3]

This Supreme Court case specifically dealt with a female-to-male (FTM) transgender person who, as a legal husband, became the father of a child born to his wife via AID. The legal landscape can differ for other scenarios:

- Unmarried FTM individual whose partner has a child via AID: The presumption of legitimacy under Article 772 would not apply, as there is no marriage. Establishing legal parentage would require different legal avenues, likely acknowledgment or adoption.

- Male-to-female (MTF) transgender person whose preserved sperm is used by a female partner to conceive: If the MTF individual is legally female, she cannot legally marry her female partner in Japan (as of 2022/2023, when the PDF commentary was written). Thus, no presumption of legitimacy would arise. Complex questions then emerge: could the MTF individual (sperm provider, legally female) be recognized as a father, or perhaps as another mother? A 2022 Tokyo High Court decision reportedly denied a child's suit to have a legally female sperm provider recognized as the father, citing the lack of legal basis for a "female father" and the absence of a biological mother-child link. [cite: 3]

These varying situations underscore the ongoing need to clarify whether terms like "father" and "mother" in legal documents are tied strictly to legal gender or if biological connections and consent to ART also play defining roles. [cite: 4]

Conclusion: Affirming Rights, Navigating Complexities

The Supreme Court's 2013 decision was a groundbreaking moment for the legal recognition of families headed by transgender individuals in Japan. By extending the presumption of legitimacy to a child born via AID to the wife of a transgender man, the Court affirmed that the legal status and rights conferred by marriage should apply, underscoring the GID Special Act's intent to integrate transgender individuals into existing legal frameworks according to their affirmed gender.

This ruling provided crucial clarity and support for transgender parents, particularly in the context of assisted reproduction. While the existence of strong dissenting opinions and the ongoing evolution of laws related to ART indicate that societal and legal discussions are far from over, this decision stands as a significant precedent in the ongoing effort to ensure that family law adapts to the diverse realities of modern family formation. It champions a more inclusive understanding of parenthood, grounded in legal marriage and intent, even when biological ties take a different form.