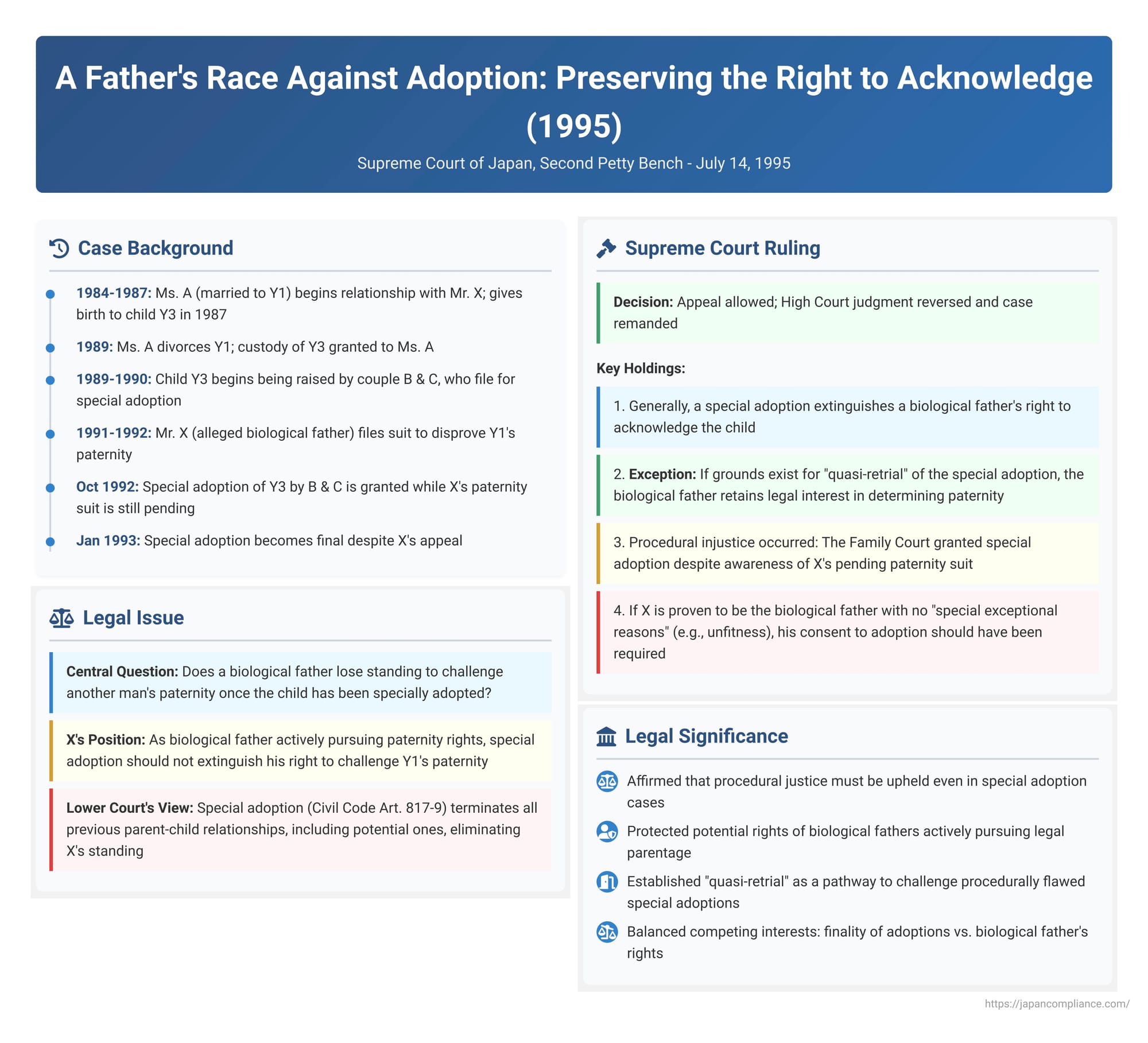

A Father's Race Against Adoption: Preserving the Right to Acknowledge in the Face of Finality

Judgment Date: July 14, 1995 (Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench)

In a complex case weaving through the intricacies of paternity challenges and Japan's "special adoption" system, the Supreme Court in 1995 delivered a significant ruling on the rights of an alleged biological father. The decision in this "Action for Confirmation of Non-existence of Parent-child Relationship" (親子関係不存在確認請求事件, Oyako Kankei Fusonzai Kakunin Seikyū Jiken) addressed whether a biological father loses his legal standing to dispute the paternity of another man once his child has been specially adopted by third parties, especially if the adoption occurred while his own paternity claim was actively being pursued. The Court carved out a crucial exception, holding that if the special adoption itself is tainted by procedural flaws warranting a "quasi-retrial," the biological father's interest in establishing his own paternity remains.

A Complex Family Saga: Marital Breakdown, New Relationships, and Disputed Paternity

The case involved Ms. A and Mr. Y1, who were married and had three children. Around 1982, their relationship soured, leading to an in-household separation, followed by a physical separation in March 1984. During this period of marital strife, around 1982, Ms. A became romantically involved with Mr. X, the plaintiff in this action.

From her relationship with Mr. X, Ms. A gave birth to two more children: Y2 in March 1984, and Y3 (the child at the center of this Supreme Court appeal) in January 1987. Both Y2 and Y3 were registered on the family register (koseki) as the legitimate children of Ms. A and her then-husband, Mr. Y1. However, Ms. A's relationship with Mr. X also deteriorated around the summer of 1986, and Mr. X only learned of Y3's birth after it had occurred.

On June 28, 1989, Ms. A and Mr. Y1 formally divorced by mutual agreement. Ms. A was granted parental authority over Y2 and Y3.

Parallel Legal Battles: A Paternity Challenge and a Special Adoption

In November 1989, a different couple, Mr. B and Ms. C, began raising Y3. In 1990, Mr. B and Ms. C filed a petition with the Family Court to "specially adopt" (特別養子, tokubetsu yōshi) Y3. Special adoption in Japan is a distinct form of adoption that generally severs all legal ties between the child and their biological family, creating a relationship akin to that of a biological child with the adoptive parents.

Meanwhile, Mr. X, believing himself to be the biological father of Y2 and Y3, took steps to establish his legal parentage. In April 1991, he initiated mediation proceedings to confirm the non-existence of a parent-child relationship between Mr. Y1 (Ms. A's ex-husband and the children's registered father) and both Y2 and Y3. When mediation was unsuccessful, Mr. X filed a formal lawsuit in June 1992 for the same purpose (the "Non-parentage Suit"). His ultimate goal was to clear the path for his own legal acknowledgment of Y2 and Y3 as his children.

The two legal processes—Mr. X's Non-parentage Suit and B & C's Special Adoption Proceeding for Y3—moved forward concurrently.

- On October 16, 1992, the Family Court issued a judgment granting the special adoption of Y3 by Mr. B and Ms. C (the "Special Adoption Judgment").

- Mr. X filed an immediate appeal against this Special Adoption Judgment, but his appeal was dismissed. The Special Adoption Judgment became final and legally binding on January 19, 1993.

- Subsequently, on March 26, 1993, the first instance court in Mr. X's Non-parentage Suit ruled in his favor, confirming the non-existence of a parent-child relationship between Mr. Y1 and Y2, and also between Mr. Y1 and Y3.

Y3 (now represented by his adoptive parents, B and C) appealed the part of this Non-parentage Suit judgment concerning the relationship between Y1 and Y3. The Sendai High Court, on November 30, 1993, reversed the first instance judgment with respect to Y3. It dismissed Mr. X's claim concerning Y3, reasoning that once a child has been specially adopted, Japanese law (Civil Code Art. 817-9) prohibits subsequent acknowledgment by the biological father. Therefore, the High Court concluded, Mr. X no longer had a legal interest in seeking confirmation of non-parentage between Y1 and Y3 because, even if successful, he could no longer acknowledge Y3. (The non-parentage judgment concerning Y2 became final, as it was not part of this appeal).

Mr. X then appealed the Sendai High Court's dismissal of his claim regarding Y3 to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Intervention: Procedural Justice and the Path to Acknowledgment

The Supreme Court overturned the Sendai High Court's decision and remanded the case back to the High Court for further consideration. The Supreme Court's reasoning was nuanced:

- General Rule on Legal Interest: A biological father typically has a recognized legal interest in filing a lawsuit to confirm the non-existence of a parent-child relationship between his child and the child's legally registered father (in this case, Y1). This interest stems from the necessity of such a confirmation to enable the biological father to then legally acknowledge the child himself.

- Effect of Special Adoption on This Interest: Ordinarily, when a special adoption judgment for the child becomes final, this legal interest of the biological father is extinguished. This is because a special adoption severs all legal ties with the biological family, including the unacknowledged biological father's potential right to acknowledge the child.

- The Crucial Exception – Grounds for "Quasi-Retrial" of the Special Adoption: However, the Supreme Court introduced a critical exception. If the Special Adoption Judgment itself is vitiated by grounds that would warrant a "quasi-retrial" (準再審, jun-saishin – a procedure analogous to retrial for certain non-contentious family court judgments), then the possibility of the biological father acknowledging the child in the future (should the adoption be overturned via such a quasi-retrial) is revived. In such circumstances, the biological father's legal interest in pursuing the Non-parentage Suit is not lost.

The Court then applied this principle to the facts of Mr. X's case:

- Procedural Injustice in the Special Adoption Proceeding:

- Mr. X had consistently asserted his biological paternity of Y3 from the moment he learned of Y3's birth. He had actively pursued legal avenues (mediation, followed by the Non-parentage Suit) specifically to enable his acknowledgment of Y3.

- Critically, the judge presiding over the Special Adoption Proceeding for Y3 was aware of Mr. X's claims and the existence of his pending Non-parentage Suit (Mr. X had submitted information to that court).

- Given these facts, the Supreme Court stated that unless there were "special exceptional reasons" – such as grounds under Civil Code Article 817-6 proviso (e.g., parental unfitness of Mr. X due to abandonment, abuse, etc., which would make his consent to the adoption unnecessary) – it was impermissible for the Family Court judge to grant the special adoption of Y3 while Mr. X's Non-parentage Suit was still pending and its outcome undetermined.

- The Court reasoned that allowing the special adoption to proceed under these conditions, knowing it would extinguish Mr. X's right to acknowledge Y3 if he was indeed the biological father, constituted a significant violation of procedural justice ("著しく手続的正義に反する," ichijirushiku tetsuzuki-teki seigi ni hansuru). It was fundamentally unfair for a court to close off Mr. X's path to asserting his parental rights when he was actively litigating them and the adoption court was aware of his efforts.

- Grounds for Quasi-Retrial of the Special Adoption Judgment:

- If Mr. X was, in fact, Y3's biological father, and if no "special exceptional reasons" (under Art. 817-6 proviso) existed, then the judge in the Special Adoption Proceeding should have awaited the outcome of Mr. X's Non-parentage Suit.

- Had the judge done so, and had Mr. X succeeded in disproving Y1's paternity, Mr. X could then have legally acknowledged Y3. As Y3's acknowledged legal father, Mr. X would have been entitled to participate as a party in the Special Adoption Proceeding, with significant rights, including (in most cases) the right to consent or refuse consent to the adoption.

- Therefore, the Special Adoption Judgment was issued without following proper procedure and without giving a person who should have been a party (Mr. X, if his claims were true) the opportunity to participate. This failure to provide an opportunity to be heard to a necessary party constituted grounds for a quasi-retrial of the Special Adoption Judgment. The Court referenced the then-applicable procedural laws, analogous to Article 420(1)(iii) of the old Code of Civil Procedure (now Article 338(1)(iii) of the current Code), which deals with situations where a party was improperly prevented from representation or participation in legal proceedings.

- Conclusion on Legal Interest:

- Consequently, the Sendai High Court had erred in law by concluding that Mr. X's legal interest in the Non-parentage Suit regarding Y3 was automatically lost merely because the Special Adoption Judgment had become final. The potential for a quasi-retrial of that adoption meant X's interest could still be live.

- The Supreme Court remanded the case to the Sendai High Court for further proceedings. This would involve determining two key factual issues: (1) whether Mr. X was indeed the biological father of Y3, and (2) whether any "special exceptional reasons" existed that would have justified proceeding with Y3's special adoption despite Mr. X's pending claims and without his consent.

The Significance of the Ruling

This 1995 Supreme Court decision was highly significant for several reasons:

- Affirmation of Quasi-Retrial for Special Adoptions: It confirmed that special adoption judgments, despite their finality, could be subject to quasi-retrial under certain conditions, particularly for severe procedural flaws. This influenced the later explicit inclusion of "retrial" provisions for family adjudications in Japan's current Domestic Relations Case Procedure Act.

- Protection of Biological Father's Procedural Rights: The ruling underscored the importance of procedural justice for unacknowledged biological fathers who are actively seeking to establish their legal parentage. It established that courts handling special adoption petitions cannot simply ignore ongoing, legitimate legal efforts by an alleged biological father to assert his rights, especially if aware of them.

- Conditional Nature of Legal Interest: It clarified that while a finalized special adoption generally terminates a biological father's right to acknowledge (and thus his interest in a prior non-parentage suit), this is not absolute if the adoption itself is procedurally challengeable in a way that could revive the acknowledgment right.

- The Role of Civil Code Article 817-6 (Parental Consent in Special Adoptions): The judgment highlighted the importance of the biological parents' consent for special adoption. The "special exceptional reasons" refer to the proviso in Article 817-6, which allows adoption without such consent only under specific circumstances of parental unfitness (e.g., abuse, abandonment, or other conditions gravely detrimental to the child's welfare if parental consent were insisted upon). The Supreme Court indicated that a high threshold exists for invoking this proviso, especially when a biological parent is actively trying to establish a legal relationship with the child.

Subsequent Developments and Modern Context

It is worth noting that after this remand, the Sendai High Court again ruled against Mr. X, finding that "special exceptional reasons" under Article 817-6 proviso did exist, thus justifying the special adoption without X's consent. However, Mr. X appealed again, and in a subsequent decision in 1998 (Heisei 10), the Supreme Court again reversed the Sendai High Court, indicating a very stringent application of the criteria for overriding a biological parent's (potential) right to object.

Since 1995, Japanese civil procedure laws have undergone substantial reforms, including the current Code of Civil Procedure, the Personal Status Litigation Act, and the Domestic Relations Case Procedure Act. Today, non-parentage suits are also handled by the Family Court (which handles adoptions), and more streamlined avenues for appeal, such as "appeal with permission to the Supreme Court," might allow for earlier intervention by the highest court in such entangled matters.

Nevertheless, the core principles articulated in the 1995 decision regarding the importance of procedural justice for individuals seeking to establish parentage, and the conditional impact of a special adoption on those rights, remain highly relevant.

Conclusion: Balancing Finality with Fairness in Complex Family Cases

The 1995 Supreme Court decision serves as a crucial reminder of the judiciary's role in safeguarding procedural fairness, even in highly sensitive family law matters like special adoption. It established that a biological father's quest to legally acknowledge his child cannot be summarily dismissed by a special adoption decree if that decree was issued under circumstances that denied him a fair opportunity to have his claims heard and his potential parental rights considered. By linking the ongoing viability of a paternity challenge to the potential for a quasi-retrial of the adoption itself, the Court provided a narrow but vital pathway to ensure that substantive rights are not extinguished by procedurally flawed adjudications. This case underscores the delicate balance Japanese law attempts to strike between the child's need for a stable adoptive family, the finality of court judgments, and the fundamental rights of biological parents.