A Father's Intent: How Japan's Supreme Court Interprets Flawed Birth Registrations as Paternal Acknowledgment

Judgment Date: February 24, 1978 (Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench)

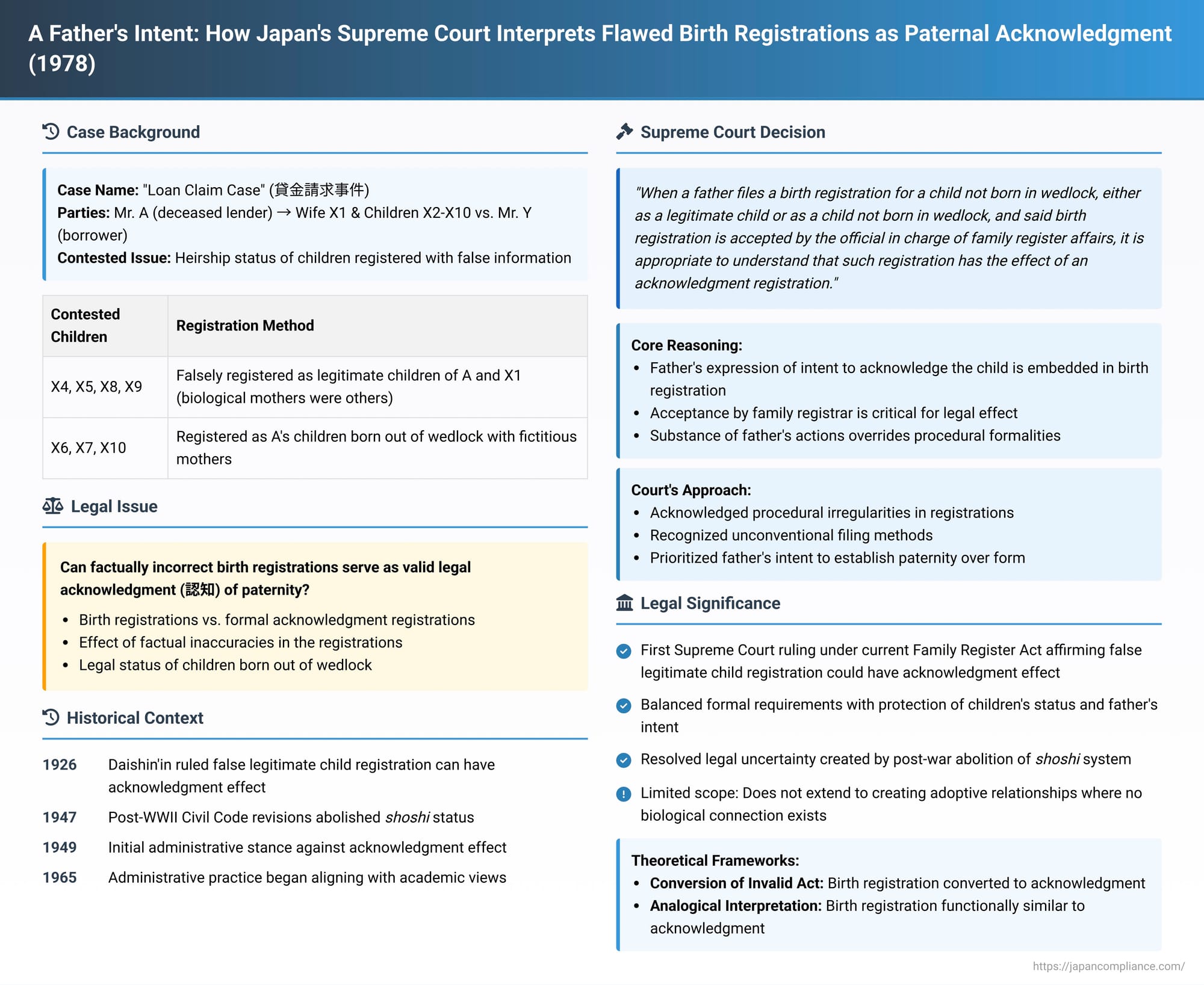

In a significant decision impacting family law and the determination of parentage, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed the legal effect of factually incorrect birth registrations. The case, commonly referred to as the "Loan Claim Case" (貸金請求事件, Kashikin Seikyū Jiken), delved into whether birth notifications containing false information, or filed in a manner not strictly prescribed by law, could nevertheless serve as a valid legal acknowledgment (認知, ninchi) of paternity by a father for children born out of wedlock. The Court's affirmative answer highlighted a pragmatic approach, prioritizing the father's discernible intent to claim parentage over strict adherence to procedural formalities, provided the registration was accepted by the family registrar.

Background of the Dispute: A Loan, A Death, and Disputed Heirs

The case originated from a loan agreement. Mr. A, a national of the Republic of China (ROC), had lent 2 million yen to Mr. Y in March 1966, with the repayment due on May 30, 1966. Mr. A passed away on June 21, 1966. Following his death, Mr. A's wife, Ms. X1, and his nine children, X2 through X10 (the plaintiffs/appellees), asserted that they had inherited Mr. A's assets, including the claim against Mr. Y, in accordance with ROC Civil Code provisions governing inheritance and "public co-ownership" (公同共有, kōdō kyōyū), which is analogous to joint ownership in Japanese law. They subsequently sued Mr. Y for the repayment of the 2 million yen plus damages for late payment.

Mr. Y, the defendant/appellant, contested the heirship status of several of Mr. A's children. Specifically:

- For children X4 and X5, their biological mother was a Ms. B. However, Mr. A had filed birth registrations falsely declaring them as legitimate children born to himself and his wife, Ms. X1.

- Similarly, for children X8 and X9, their biological mother was a Ms. C. Mr. A had also registered them as legitimate children of himself and Ms. X1.

- For children X6, X7, and X10, Mr. A had registered them as his children born out of wedlock to a fictitious mother, with Mr. A himself acting as the informant on the birth notification.

The central legal issue that emerged was whether these false birth registrations—either misrepresenting children born out of wedlock as legitimate, or filed by the father for a child born out of wedlock (with a non-existent mother)—could be recognized as having the legal effect of an acknowledgment of paternity by Mr. A. Both the court of first instance (Tokyo District Court, December 21, 1973) and the appellate court (Tokyo High Court, December 9, 1975) found that the birth registrations did indeed carry the force of acknowledgment. Mr. Y appealed this determination to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Ruling

The Supreme Court dismissed Mr. Y's appeal, upholding the lower courts' decisions.

The Court first addressed a preliminary point concerning the applicable law. It affirmed the lower court's finding that Mr. A was an ROC national at the time of his death. Therefore, under Japan's conflict of laws rules at the time (the Hōrei, 法例), ROC law governed matters of his succession (Article 25 of Hōrei) and any acknowledgment he made (Article 18 of Hōrei). This application of ROC Civil Code was deemed appropriate.

The core of the judgment then turned to the effect of the disputed birth registrations:

"Regarding the second point of the grounds for appeal:

When a father files a birth registration for a child not born in wedlock, either as a legitimate child or as a child not born in wedlock, and said birth registration is accepted by the official in charge of family register affairs, it is appropriate to understand that such registration has the effect of an acknowledgment registration. This is because, although such registrations are not primarily intended for the acknowledgment of a child, and a birth registration of a child not born in wedlock as a legitimate child contains factual inaccuracies regarding the mother's description, and further, the law does not anticipate a father filing a birth registration for a child not born in wedlock (and even if a father happens to file such a registration, it is merely considered as filed in the capacity of a cohabitant (see Family Register Act, Article 52, Paragraphs 2 and 3)), an acknowledgment registration is an expression of intent by the father to the official in charge of family register affairs, acknowledging a child not born in wedlock as his own child and declaring that fact. Such birth registrations also include, in addition to the father reporting the child's birth to the official in charge of family register affairs, an expression of intent by the father to acknowledge the born child as his own and declare that fact. Therefore, as long as these registrations have been accepted by the official in charge of family register affairs, there is no impediment to recognizing them as having the effect of an acknowledgment registration."

The Court found the lower court's findings and reasoning on other points to be sound and devoid of legal error. It also upheld the lower court's presumption that there was mutual consent among the appellees (X1-X10) for each to claim the full amount of the loan and accrued interest. Accordingly, the appeal was dismissed.

Unpacking the Rationale: Intent Over Formality

The Supreme Court's reasoning, while concise, is profound. It acknowledges the procedural and factual irregularities in the birth registrations:

- Not Primary Purpose: These filings were birth registrations (出生届, shusshō todoke), not formal acknowledgment registrations (認知届, ninchi todoke). Their primary stated purpose was to report a birth.

- Factual Inaccuracies: In the cases of X4, X5, X8, and X9, the registrations falsely named Ms. X1 as the mother, thus incorrectly presenting them as legitimate children (嫡出子, chakushutsushi).

- Unconventional Filer: For children born out of wedlock (非嫡出子, hi-chakushutsushi) like X6, X7, and X10, the Family Register Act (戸籍法, Koseki Hō) primarily designates the mother as the person to file the birth registration (Article 52, Paragraph 2). While a father can file, if he does so not as the mother's representative but in another capacity (e.g., as a cohabitant, under Article 52, Paragraph 3), the law doesn't specifically envision him filing "as the father" for an illegitimate child in the standard birth registration process. The Court noted that if a father files for an illegitimate child, it's generally viewed as if he's acting as a "cohabitant."

Despite these issues, the Court focused on the substance of the father's actions:

- An acknowledgment, at its core, is a declaration by the father to the relevant authority (the family registrar, 戸籍事務管掌者, koseki jimu kanshōsha) that he recognizes a particular child born out of wedlock as his own.

- The Court found that these flawed birth registrations, irrespective of their primary label or inaccuracies, inherently contained such a declaration of paternity by Mr. A. By filing these documents, Mr. A was expressing his intent to the registrar that these children were his.

- Crucially, the acceptance of these registrations by the family registrar was seen as a vital step. Once accepted, the father's declared intent, embedded within the registration, could be given legal effect as an acknowledgment.

This decision marked a significant moment in Japanese family law, particularly regarding the interplay between formal registration requirements and the underlying intent to establish legal parentage.

Historical and Legal Evolution Leading to the 1978 Decision

The Supreme Court's 1978 ruling did not emerge in a vacuum. It built upon a history of legal interpretation and evolving societal understanding of acknowledgment.

1. Pre-War Context: The Shoshi System

Under the Meiji Civil Code (旧民法, Kyū Minpō), an illegitimate child acknowledged by the father was termed a shoshi (庶子). The original Meiji 31 (1898) Family Register Act included provisions for a father to file a shoshi birth registration, but this act of registration itself was not initially deemed to have the effect of acknowledgment. A separate act of acknowledgment was typically required.

A pivotal early precedent came from the Daishin'in (大審院, the pre-WWII Supreme Court) on October 11, Taisho 15 (1926). In that case, a father had registered his child born to a mistress as a legitimate child. The Daishin'in held that this registration, despite its falsity regarding legitimacy, "contained the father's expression of intent to recognize the child as his own" and therefore should be considered to have the effect of acknowledgment of a non-marital child. This was a key early instance of looking beyond the form to the father's intent.

Subsequently, the Family Register Act was amended in Taisho 3 (1914). The amended law (Old Koseki Ho Article 83, first part) explicitly granted acknowledgment effect to a father's filing of a shoshi birth registration. Following this, family registration practice evolved to treat a false legitimate child registration by a father as equivalent to a shoshi birth registration by him, thus granting it acknowledgment effect. This administrative practice relied on the statutory basis provided by the amended Old Koseki Ho for shoshi registrations, rather than solely on the Daishin'in's interpretive approach.

2. Post-WWII Reforms and Emerging Uncertainty

The post-WWII revision of the Civil Code in Showa 22 (1947) abolished the shoshi status. Consequently, the provision in the Old Family Register Act (Article 83, first part) concerning a father's shoshi birth registration and its acknowledgment effect was removed from the current Family Register Act. This deletion created a legal gray area: could a false legitimate child birth registration still be considered an acknowledgment under the new legal framework that lacked the shoshi system?

Initially, post-war family registration administrative circulars (e.g., a Civil Affairs Bureau Director's response dated September 19, 1949) took a negative stance. The reasoning was that the shoshi system no longer existed, and acknowledgment was a formal act requiring specific procedures; therefore, a false legitimate child registration could not be treated as an acknowledgment.

3. Academic Support for Acknowledgment Effect

Despite this initial administrative stance, a majority of legal scholars argued in favor of granting acknowledgment effect to such registrations. Their arguments included:

- Father's Intent: Echoing the 1926 Daishin'in ruling, they asserted that the father's intention to recognize the child as his own was evident in the act of filing the birth registration, even if it contained inaccuracies about the child's legitimacy or the mother.

- Substantive Grounds: They pointed out that while the specific provision for shoshi registration was gone, the current Family Register Act (Article 62) still recognized that a legitimate child birth registration for a child who could be legitimized by subsequent marriage and acknowledgment (as per Civil Code Article 789, Paragraph 2) could have the effect of acknowledgment. This suggested a continuing substantive basis for recognizing acknowledgment through birth registrations in certain contexts.

- Child Welfare: A strict denial of acknowledgment effect would necessitate separate, often more complex, acknowledgment procedures. If the father had died, this could involve a posthumous acknowledgment lawsuit, which has strict time limits (Civil Code Article 787). Failing to recognize the birth registration as acknowledgment could thus unfairly prejudice the child by foreclosing opportunities to establish legal paternity.

Over time, administrative practice began to align with this prevailing academic view, even before the 1978 Supreme Court decision (e.g., a Civil Affairs Bureau Director's circular dated January 7, 1965).

4. Significance of the 1978 Supreme Court Decision

The 1978 ruling was groundbreaking because it was the Supreme Court's first definitive statement under the current Family Register Act affirming that a false legitimate child birth registration (where the father registers a child born out of wedlock as his legitimate child with his wife) could indeed have the effect of acknowledgment.

Furthermore, the decision also addressed the distinct scenario where the father himself files a birth registration for his child born out of wedlock as an illegitimate child (as seen with X6, X7, and X10, who were registered with a fictitious mother).

- Under the Old Koseki Ho, a father could file a shoshi birth registration.

- The current Koseki Ho, as mentioned, doesn't explicitly provide for a father to file for an illegitimate child in his capacity as "father" (the mother is the primary filer).

- Previous administrative directives (e.g., responses from April 21, 1948, and April 15, 1949) stated that such filings by a father (as father) should not be accepted, and if mistakenly accepted, would not have acknowledgment effect.

- However, many scholars argued that the logic of the 1926 Daishin'in precedent (focusing on the father's intent) should apply equally to these situations.

The 1978 Supreme Court judgment was the first to rule that a father's birth registration of an illegitimate child (even if containing irregularities like a fictitious mother) could have the effect of acknowledgment, importantly adding the condition "once accepted by the family registrar." Subsequent administrative circulars (e.g., a Civil Affairs Bureau Director's circular dated April 30, 1982) aligned official practice with this Supreme Court ruling for both types of problematic birth registrations.

Theoretical Underpinnings: Conversion of Acts or Analogical Interpretation?

While the Supreme Court's judgment focuses on the interpretation of the father's intent contained within the birth registration, legal scholars have debated the precise theoretical framework for this outcome.

1. Conversion of an Invalid Act (無効行為の転換, mukō kōi no tenkan)

One prominent theory is that the Court's decision relies on the doctrine of "conversion of an invalid act." This doctrine, found in general civil law principles, allows an act that is invalid for its intended purpose to be given effect as a different type of valid act, provided certain conditions are met (e.g., the parties would have intended the valid act had they known of the invalidity, and the requirements for the valid act are fulfilled).

In this context:

- A birth registration falsely claiming legitimacy, or a father's birth registration for an illegitimate child that doesn't meet strict procedural norms, might be considered "invalid" or "improper" as a birth registration in those specific aspects.

- However, because it contains the father's clear intent to claim paternity, it can be "converted" into a valid acknowledgment.

This view is supported by the fact that the Supreme Court's ruling encompassed not only false legitimate child registrations but also father-filed illegitimate child registrations, the latter being a type of filing not explicitly provided for in the law when made by the father in his capacity as "father." Some scholars argue that since such a filing is, in a sense, legally non-existent as a category, its effect as acknowledgment is best explained through conversion.

2. Analogical Interpretation of Family Register Act Article 62

Another perspective suggests that the basis is an analogical interpretation of Article 62 of the Family Register Act. This article deals with the registration of a child born before the parents' marriage who is subsequently legitimized. It implies that a birth registration can sometimes fulfill the function of an acknowledgment. This view posits that the birth registration itself isn't entirely invalid; rather, the aspects relating to legitimacy are incorrect, but the core act of registering the child by the father still holds significance that can be analogously linked to acknowledgment.

Addressing Potential Objections to the Conversion Theory:

Scholars favoring the conversion theory have addressed potential counterarguments:

- Differing Nature of Filings: Birth registrations are generally considered "declaratory notifications" (報告的届出, hōkokuteki todokeide), reporting a factual event. Acknowledgment registrations are "constitutive notifications" (創設的届出, sōsetsuteki todokeide), creating a new legal status. However, it's argued that acknowledgment, unlike acts like marriage or divorce by agreement, largely rests on the father's recognition of an existing biological fact (his paternity). The legal effect (creation of a legal parent-child relationship) flows from this declaration of fact. Therefore, the two types of acts are not so fundamentally different as to preclude conversion, especially since no special provision is deemed necessary to allow such conversion.

- Formality of Acknowledgment: Acknowledgment is a formal act requiring a notification as prescribed by the Family Register Act. Allowing a birth registration to substitute for this might seem to undermine this formality. However, the purpose of the formality is to ensure the father's definite and clear intent. If this intent is unequivocally present in the birth registration filed by the father, the strict adherence to the form of an "acknowledgment registration" might not be indispensable. Moreover, the Family Register Act and its regulations do not rigidly prescribe a single, unalterable format for acknowledgment; as long as the essential elements are present and accepted, the form itself is not the paramount concern.

The 1978 Supreme Court judgment itself does not explicitly state which theory it adopts, but its emphasis on the father's discernible intent and the acceptance by the registrar provides a practical solution that resonates with the underlying principles of protecting the child's status by recognizing the father's wish to establish legal parentage.

Scope and Limitations: Not a Universal Conversion

It is crucial to understand the limits of this principle. The Court's willingness to find acknowledgment effect in flawed birth registrations for biological children does not extend to creating entirely different legal relationships where no biological tie exists.

No Conversion to Adoption:

The courts have consistently refused to allow a false birth registration or an acknowledgment registration to be "converted" into an adoption registration (養子縁組届, yōshi engumi todoke) if there is no biological parent-child relationship.

- For instance, if individuals falsely register a non-biological child as their own, this act cannot later be treated as a valid adoption if challenged. The Supreme Court (e.g., decision of April 8, 1975) has maintained that adoption has distinct objectives, stringent requirements (including the intent to adopt), and formalities that differ significantly from birth or acknowledgment registrations.

- Similarly, an adoption registration cannot generally be converted into an acknowledgment registration (Daishin'in decision, July 4, 1929, although a later Supreme Court case from October 3, 1952, allowed for ratification by the adopted person under specific circumstances).

The distinction lies in the nature of the relationship being established. The 1978 ruling concerns the establishment of legal parentage based on an existing (though perhaps irregularly declared) biological connection. Adoption, conversely, creates a legal parent-child relationship where one typically does not exist biologically. The law views these as fundamentally different processes with different safeguards and intentions. The 1978 case affirms acknowledgment where there's a blood tie, facilitated by the father's (albeit imperfect) declaration.

A Related Scenario: Father Filing as "Cohabitant"

A related question arises: what if the father of a child born out of wedlock files the birth registration not explicitly as "father," but in the capacity of a "cohabitant" (同居者, dōkyosha)? The Family Register Act (Article 52, Paragraph 3) permits a cohabitant to file a birth registration if the mother is unable to do so.

In the 1978 case, Mr. A, as the father, was the informant on the registrations. His paternal status was explicitly part of the filing. If a father files merely as a "cohabitant," his name might appear as the informant, but his explicit declaration "I am the father" might be absent from that specific field on the form.

However, legal commentators suggest that the spirit of the 1978 Supreme Court decision could extend to such situations. If, despite filing as a cohabitant, the father's intent to acknowledge the child as his own can be clearly established through the overall circumstances or other evidence accompanying the registration process, then acknowledgment effect might still be recognized. The critical factor remains the ascertainable intent of the father to claim paternity, communicated to the registrar and leading to an accepted registration.

Conclusion: Balancing Formalities with Substantive Justice

The Supreme Court's February 1978 decision is a landmark in Japanese family law for its nuanced approach to the legal consequences of flawed birth registrations. By prioritizing the father's discernible intent to acknowledge paternity and the subsequent acceptance of the registration by the family registrar, the Court opted for a path that emphasizes substantive justice and the protection of the child's status over rigid adherence to procedural perfection.

The ruling acknowledges the complexities of human relationships and the various ways paternal bonds might be declared, even if those declarations fall short of prescribed legal forms. It underscores a judicial willingness to look at the reality of the father's actions and their intended meaning, particularly when the establishment of a legal parent-child relationship is at stake. While carefully circumscribed—not extending to the creation of non-biological ties like adoption through such conversions—the decision provides crucial flexibility in recognizing paternity, thereby ensuring that children are not unduly disadvantaged by formal irregularities in the registration of their birth and paternal lineage.