A Father's Ghost? The Japanese Supreme Court on Children Conceived After Death

Judgment Date: September 4, 2006 (Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench)

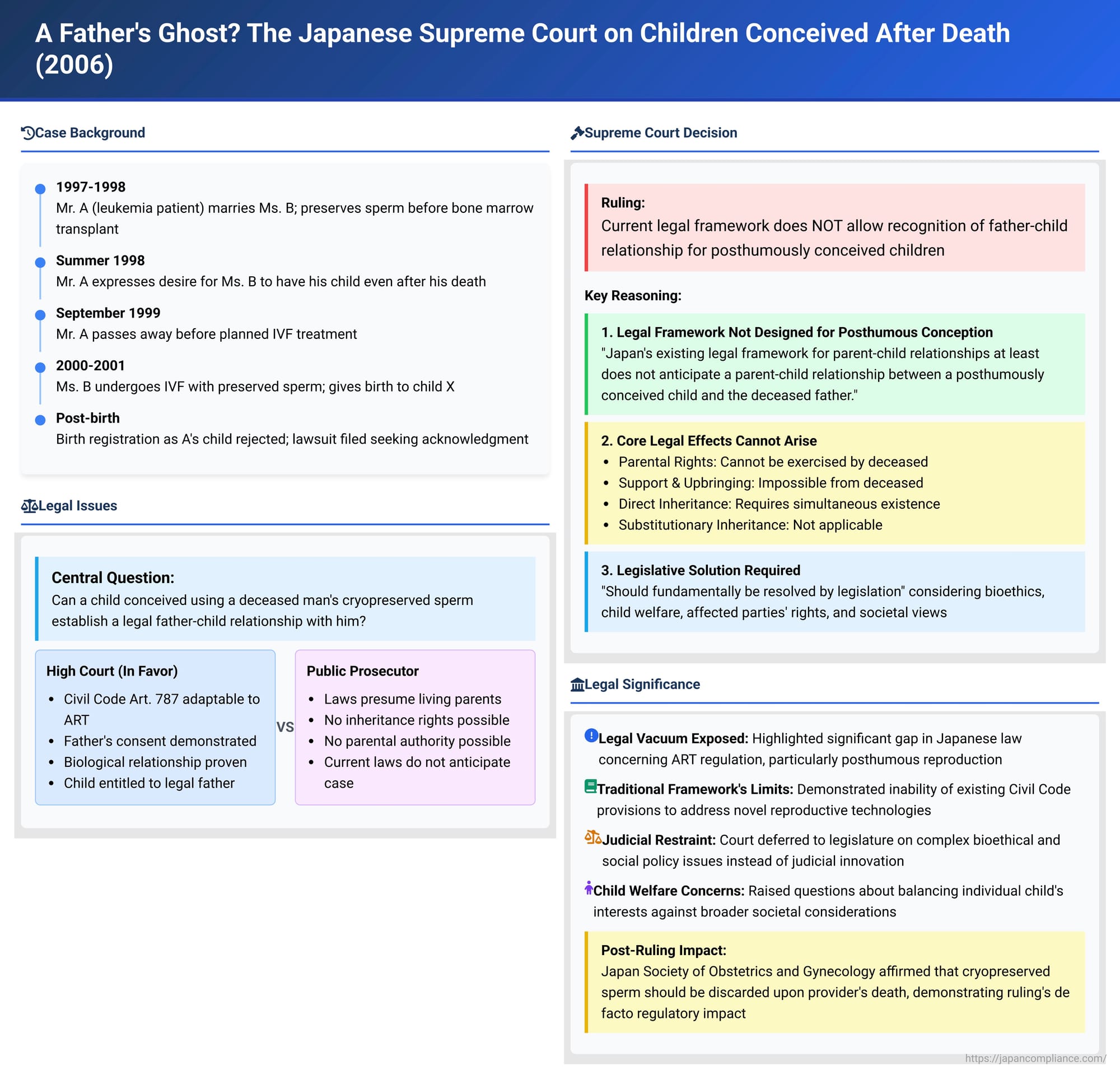

In an era of rapidly advancing medical technology, a poignant and legally complex question reached Japan's highest court: can a child conceived using a deceased man's cryopreserved sperm establish a legal father-child relationship with him? The Supreme Court's 2006 decision in an "Acknowledgment Claim Case" (認知請求事件, Ninchi Seikyū Jiken) delivered a clear, albeit difficult, answer: under Japan's existing legal framework, such a relationship cannot be recognized. The ruling underscored the limits of current laws in addressing the novel scenarios created by assisted reproductive technologies (ART) and called for legislative action.

A Couple's Dream, a Husband's Illness, and a Legacy in Ice

The case involved a married couple, Mr. A and Ms. B, who wed in 1997. They embarked on fertility treatments soon after their marriage. Mr. A had been undergoing treatment for leukemia prior to the marriage and was subsequently scheduled for a bone marrow transplant. Concerned that the radiation therapy associated with the transplant would render him infertile, Mr. A had his sperm cryopreserved in June 1998.

Mr. A expressed his wishes regarding fatherhood on multiple occasions. In the summer of 1998, before his transplant, he told Ms. B that if he were to die and she did not remarry, he wanted her to have his child. After the surgery, he conveyed to his parents his desire that, should anything happen to him, Ms. B should use his preserved sperm to have a child who could continue the family line. He later shared similar sentiments with his brother and aunt.

In May 1999, after Mr. A's transplant was successful and he had returned to work, the couple made plans to resume fertility treatments, intending to use the cryopreserved sperm for in vitro fertilization (IVF). Arrangements were made with a clinic for this purpose. However, before the IVF procedure could be carried out, Mr. A passed away in September 1999.

Despite Mr. A's death, Ms. B, after consulting with his parents, decided to proceed with the IVF treatment using his cryopreserved sperm. In 2000, she underwent the procedure, and in May 2001, she gave birth to a child, X (the plaintiff in this case).

Complicating the matter of intent, the sperm cryopreservation request form signed by Mr. A reportedly contained a clause stating that the sperm would not be used after his death. Furthermore, Ms. B had not informed either the hospital where the sperm was stored or the clinic where the IVF was performed that Mr. A had died.

The Legal Battle for a Father's Name

Following X's birth, Ms. B attempted to register X as the legitimate child of herself and Mr. A. However, this birth registration was not accepted by the authorities. (This refusal itself was reportedly upheld in an unrecorded Supreme Court decision on April 24, 2002 ).

Undeterred, Ms. B, acting as X's legal representative, filed a lawsuit against the public prosecutor (Y, the defendant, as is standard in posthumous acknowledgment cases) seeking legal acknowledgment that X was Mr. A's child.

The court of first instance (Matsuyama District Court, November 12, 2003) dismissed X's claim. However, the appellate court (Takamatsu High Court, July 16, 2004) reversed this decision and ruled in favor of X, ordering the acknowledgment. The High Court reasoned that:

- While Japan's Civil Code Article 787 (governing suits for acknowledgment) was enacted when only natural reproduction existed, this did not inherently preclude a posthumously conceived child from seeking acknowledgment.

- Acknowledgment offers tangible legal benefits, such as establishing kinship with the father's relatives and creating the possibility of "substitionary inheritance" (daishū sōzoku, 代襲相続) – inheriting from the father's lineal ascendants (e.g., grandparents) if the father is deceased.

- For a posthumously conceived child to be acknowledged, the High Court deemed it necessary and sufficient that: there is a biological father-child relationship; the father had consented to the artificial reproduction that led to the conception; and there are no special circumstances making acknowledgment inappropriate. The High Court found these conditions to be met in X's case.

The public prosecutor then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Unanimous Verdict: Current Law Does Not Recognize Paternity for Posthumously Conceived Children

The Supreme Court unanimously overturned the High Court's decision, effectively reinstating the first instance court's dismissal of X's acknowledgment claim. The Court's reasoning was structured around three main points:

1. Japan's Parent-Child Laws Do Not Envision Posthumous Conception:

The Court began by noting that the Civil Code's provisions concerning legal parent-child relationships are fundamentally based on biological ties. While assisted reproductive technologies (ART) were initially seen as merely replacing parts of the natural reproductive process, they have advanced to the point where they can enable conceptions entirely impossible through natural means—posthumous conception being a prime example. The Court stated unequivocally that Japan's existing legal framework for parent-child relationships "at least does not anticipate a parent-child relationship between a posthumously conceived child and the deceased father."

2. Fundamental Legal Effects of Paternity Cannot Arise:

The Court then detailed why such a relationship falls outside the current legal structure by examining the core legal consequences of paternity:

- Parental Rights (親権, shinken): A father who died before the child's conception can never exercise parental rights or fulfill parental duties.

- Support and Upbringing (扶養, fuyō): A posthumously conceived child can never receive care, upbringing, or financial support directly from the deceased father.

- Inheritance from the Father (相続, sōzoku): Under Japanese law, for a child to inherit from a parent, they must exist at the time of the parent's death (the principle of simultaneous existence). A child conceived after the father's death cannot be his direct heir.

- Substitionary Inheritance Through the Father: Substitionary inheritance allows a person (e.g., a grandchild) to inherit the share their predeceased parent would have received from an ancestor (e.g., a grandparent). The Court reasoned that for this to apply in cases where the "predeceasing link" (here, Mr. A) died, the substitionary heir (X) must have been in a position to inherit from that link. Since X could not inherit from Mr. A, X could not be a substitionary heir through Mr. A either.

The Court concluded that the relationship between a posthumously conceived child and the deceased biological father is one where "the basic legal relationships provided for in the aforementioned legal system for parent-child relationships have no room to arise."

3. The Need for Comprehensive Legislation:

Given that existing laws do not cover such situations, the Supreme Court emphasized that the question of legal parentage for posthumously conceived children is a matter that "should fundamentally be resolved by legislation." Such legislation would require careful consideration from multiple perspectives, including:

- The bioethics of using a deceased person's gametes for reproduction.

- The welfare of the child born as a result.

- The perspectives and rights of all individuals who would be affected by the formation of new parent-child or kinship relationships.

- General societal views on these matters.

Only after such comprehensive deliberation could a legislative body decide whether to recognize such parent-child relationships and, if so, under what conditions and with what legal effects. In the absence of such specific legislation, the Court concluded that "the formation of a legal parent-child relationship between a posthumously conceived child and a deceased father cannot be recognized."

Justices Takii Shigeo and Imai Isao provided supplementary concurring opinions, further elaborating on these points. Justice Takii, for instance, emphasized that while natural reproduction was the premise of the Civil Code, and ART assisting living parents was acceptable, posthumous conception was contrary to the natural order of children being born to living parents and was thus beyond the scope of existing law. He stressed that the child's welfare must be considered within the broader context of what it means to create a child without a living father at conception, a matter requiring legislative, not judicial, pioneering.

The Legal and Ethical Vacuum

The Supreme Court's decision highlighted a significant gap in Japanese law concerning the regulation of ART, particularly posthumous reproduction.

At the time of the ruling:

- There was no specific legislation governing the permissibility of using cryopreserved sperm after the provider's death, nor detailing the legal status of any resulting child.

- A 2003 report from a Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare council ("Report on the Development of a System for Assisted Reproductive Technology Using Provided Sperm, Eggs, or Embryos") had recommended that gametes and embryos from deceased providers should be discarded. The reasons cited included ethical concerns, the deceased's inability to revoke consent, and the child's welfare (being born with a genetic parent already deceased).

- Concurrently, a Ministry of Justice Legislative Council working group, while discussing reforms related to parentage in ART, had explicitly refrained from tackling posthumous conception cases. It deemed it inappropriate to create specific parentage rules for such situations while the broader legal and ethical framework for ART itself remained undefined.

Interpreting Old Laws for New Realities

The courts below the Supreme Court had to grapple with applying existing Civil Code provisions to this novel situation:

- Presumption of Legitimacy (Civil Code Art. 772): This article, which presumes a child born to a wife during marriage or within 300 days of its dissolution to be the husband's child, was deemed inapplicable. X was conceived after Mr. A's death and thus after the dissolution of the marriage. Furthermore, if "legitimate child" strictly implies conception or birth during marriage to a couple with whom the child has blood ties, X would not fit this definition from the outset.

- Suit for Acknowledgment (Civil Code Art. 787): The High Court had attempted to adapt this provision by adding a requirement of the deceased father's consent to the posthumous conception. The Supreme Court, however, took a more restrictive stance, emphasizing the fundamental disconnect between the legal effects of paternity defined in the Civil Code and the reality of a child conceived after the father's death.

This situation drew comparisons to how Japanese courts handle Artificial Insemination by Donor (AID). In AID cases, conception is also not naturally possible for the married couple using the husband's sperm. Yet, the presumption of legitimacy under Article 772 is generally applied to establish the consenting husband as the legal father, not the sperm donor. The Supreme Court's approach in the posthumous conception case suggests a different threshold when the father is deceased before conception.

"Welfare of the Child" vs. Broader Societal Considerations

The concept of "child welfare" was central to the debate.

- The High Court's approach aimed to provide X with a legal father, recognizing the social and potential emotional benefits of such status.

- The Supreme Court, while acknowledging the child's innocence, seemed to weigh this against the broader implications of judicially sanctioning a practice not yet legitimized by societal consensus or specific laws. The Court pointed out that even if acknowledgment were granted, most of the typical legal benefits of paternity (parental care, direct inheritance) would not materialize for X under existing law.

- Commentators have noted that being named on the family register (koseki) has significant social meaning in Japan. Denying any possibility of legal paternity to a child born through ART, when children born naturally are always afforded such a legal link (even if through subsequent acknowledgment), could be seen as discriminatory.

- Regarding Mr. A's wish for X to "continue the family line" (which often implies inheritance), the Supreme Court's denial of direct and substitionary inheritance meant that for X to inherit from Mr. A's estate (if any, though impossible here) or Mr. A's parents, alternative legal routes like gifting, testamentary bequests from the grandparents, or adoption by the grandparents would be necessary.

Regulation, Ethics, and the Law's Reach

The case also touched upon the interplay between regulating medical practices and defining family law. While denying legal status to a child might indirectly discourage certain ART practices, some argue this is an excessive way to achieve conduct regulation, unfairly penalizing the child. Direct sanctions on medical professionals who contravene ethical guidelines might be a more appropriate deterrent.

Following this Supreme Court decision, the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology reportedly issued a statement affirming that cryopreserved sperm should be discarded upon the provider's death and that a provider's survival and current intent should be confirmed before using their gametes for ART. This illustrates the ruling's de facto regulatory impact on medical practice.

Scope and Lingering Questions

The Supreme Court's reasoning appears broadly applicable to the use of any deceased person's gametes (sperm, eggs, or embryos) for conception. This suggests that:

- Even if X had been born within 300 days of Mr. A's death (a period often relevant for presumption of legitimacy), Article 772 likely still wouldn't apply if conception occurred post-mortem. (The PDF commentary notes it's unclear if the Heisei 14.4.24 decision explicitly confirmed this point for posthumous conceptions within the 300-day window ).

- If cryopreserved embryos or eggs from a deceased woman were used to achieve a birth, legal maternity with the deceased woman might similarly be denied under this logic, although the woman who gives birth is generally recognized as the legal mother in Japan, creating a maternal link regardless of genetics.

- The situation contrasts with typical AID outcomes, where the consenting husband of the woman who gives birth is recognized as the legal father, and the (living) sperm donor is not. The ART Special Provisions Act (Law No. 76 of Reiwa 2, 2020) now reinforces that a husband who consents to AID cannot later deny paternity.

Conclusion: A Call for Legislative Clarity

The 2006 Supreme Court decision firmly established that, under the then-current and still largely unchanged fundamental Civil Code provisions, children conceived using the sperm of a man who has already died cannot gain legal recognition as his child. The judgment was a clear signal that the profound ethical, social, and legal questions raised by posthumous reproduction require deliberate and comprehensive legislative action. While the Court acknowledged the emotional complexities and the innocence of the child involved, it ultimately found that the existing legal framework was not equipped to extend the traditional understanding of parentage to these novel circumstances. The case remains a critical reference point in ongoing discussions about the legal and societal implications of assisted reproductive technologies and the evolving definition of family in the 21st century.