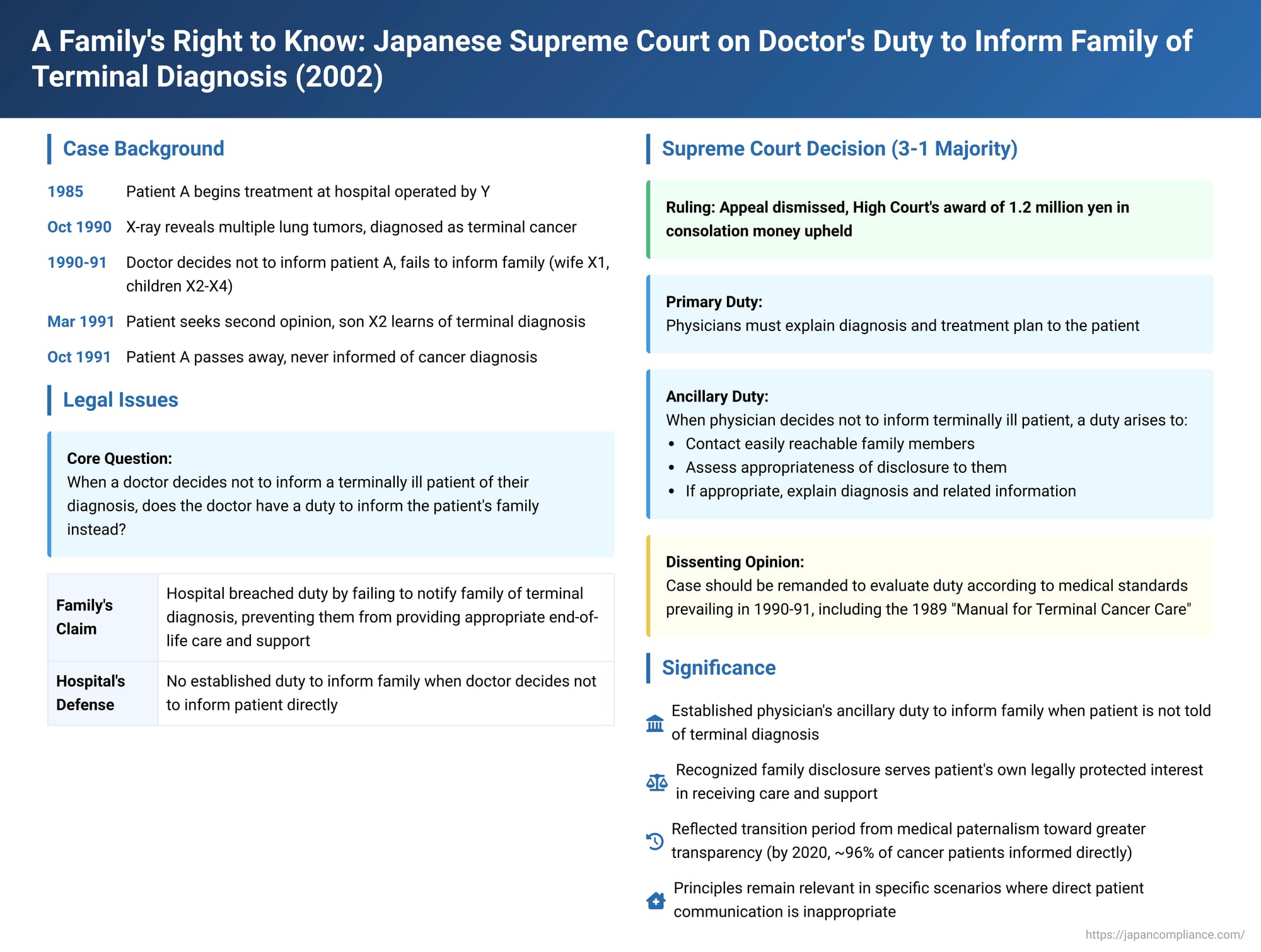

A Family's Right to Know: Japanese Supreme Court on Doctor's Duty to Inform Family of Terminal Diagnosis

Decision Date: September 24, 2002, Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench (Heisei 10 (O) No. 1046)

In a significant judgment delivered on September 24, 2002, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed the delicate issue of a physician's duty when choosing not to inform a terminally ill patient of their diagnosis. The case revolved around whether, under such circumstances, a duty arises to inform the patient's family, thereby enabling them to provide appropriate end-of-life care and support. The ruling highlighted the evolving understanding of patient rights and the responsibilities of medical professionals in Japan.

The Patient's Journey and Undisclosed Diagnosis

The case concerned a patient, A, who had been receiving treatment at a hospital operated by the defendant, Y, since 1985. In October 1990, a chest X-ray, conducted to monitor A's heart condition, unexpectedly revealed multiple lung tumors. Further examinations confirmed that A was suffering from terminal cancer with no prospect of cure or significant life extension; only palliative care for pain management was deemed possible at that stage.

The attending physician at Y hospital, Dr. F, decided against informing A directly of his terminal condition. Dr. F considered explaining the situation to A's family but was unable to find an opportunity before his tenure ended. He left a note in A's medical chart indicating that some explanation to A's family was necessary. A was married to X1, and they had three adult children, X2, X3, and X4, who were the plaintiffs in this case.

As A's chest pain persisted despite treatment at Y hospital, he, accompanied by his wife X1, sought a second opinion at B University Hospital in March 1991. There, he was diagnosed with terminal cancer. The physicians at B University Hospital informed A's eldest son, X2, of the diagnosis. A was subsequently referred by B University Hospital to C Hospital, where he had repeated admissions and discharges until his death in October 1991. Crucially, A himself was never informed that he had terminal cancer before he passed away.

The Family's Claim for Damages

A's wife (X1) and his three children (X2, X3, and X4) filed a lawsuit against Y, the operator of the initial hospital. They sought 19 million yen in consolation money, arguing that the hospital's failure to inform them of A's terminal cancer diagnosis in a timely manner constituted a breach of duty under the medical care contract or a tort. The family contended that had they known about A's condition earlier, they could have provided him with more comprehensive and considerate care, ensuring that his remaining life was as fulfilling and comfortable as possible.

Lower Court Rulings

The Akita District Court initially dismissed the family's claim. However, on appeal, the Sendai High Court (Akita Branch) partially sided with the family. The High Court held that while the decision not to inform patient A directly of his terminal cancer was justifiable under the doctrine of reasonable medical discretion prevailing at the time, this decision created a consequential duty. Specifically, since A was not informed, the hospital's physicians had a duty to promptly consider the appropriateness of informing A's family. The High Court found that the physicians had breached this duty and awarded A (through his heirs, X1-X4) 1.2 million yen as consolation money. The hospital operator, Y, then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision (September 24, 2002)

The Supreme Court, in a 3-1 majority decision, dismissed Y's appeal and upheld the High Court's ruling in favor of the family.

Majority Opinion:

The majority opinion laid out the following reasoning:

- Primary Duty to Patient: Physicians have a fundamental obligation under the medical care contract to explain the diagnosis, treatment plan, and related matters to the patient.

- Ancillary Duty to Family: However, if a physician diagnoses a patient with a terminal illness and limited life expectancy and, in their medical judgment, decides not to inform the patient directly, an ancillary duty arises. Given the profound significance of such a diagnosis for both the patient and their family, the physician is obligated, as part of the broader duties flowing from the medical contract, to at least make contact with easily reachable family members.

- Consideration and Disclosure to Family: Upon contacting the family, the physician must then assess the appropriateness of disclosing the diagnosis to those contacted, or to other family members who can be reached through them. If disclosure is deemed appropriate, the physician then has a duty to explain the diagnosis and related information to them.

- Rationale for Family Disclosure: The Court reasoned that informing the family serves a vital interest for the patient. An informed family can better understand the medical team's treatment approach, provide crucial material and emotional support, and make arrangements to ensure the patient's remaining life is as peaceful, dignified, and fulfilling as possible. This support and care from the family, facilitated by timely disclosure, constitutes a legally protected interest of the patient.

- Application to A's Case: In A's situation, the physicians at Y hospital, including Dr. F, did not adequately attempt to contact A's family, nor did they properly consider the appropriateness of informing them, despite knowing A was terminally ill. A lived with his wife, X1; his son X4 lived nearby and visited frequently; and his son X2 also resided in the same city. The hospital records contained A's home phone number and indicated X2 as the holder of A's health insurance policy (identifying A as X2's father), meaning contact was feasible. There were no apparent obstacles to informing at least X2 and X4.

- Breach of Duty: The doctors at Y hospital could have, and should have, contacted these family members and, upon assessment, found them suitable for disclosure. Their failure to do so was deemed an insufficient standard of care for a patient diagnosed with a terminal illness and limited life expectancy. This constituted a breach of their duty to make contact with and inform appropriate family members.

- Consequences of Non-Disclosure: As a direct result of this failure, A's family remained unaware of his terminal condition until the diagnosis at B University Hospital in March 1991. This delay prevented them from taking steps to help A live his remaining months according to his wishes, spend more quality time with him, and provide the fullest possible care and support to enhance his quality of life. Therefore, A (and consequently his heirs) was entitled to consolation money from Y.

Dissenting Opinion:

One justice dissented, arguing that the High Court's decision should be overturned and the case remanded.

- The core issue, according to the dissent, was the precise nature and extent of the duty owed by a medical institution regarding the disclosure of terminal cancer (specifically, stage IV cancer with no effective treatment options) to either the patient or their family under the medical care contract.

- Critically, this duty should have been evaluated based on the prevailing medical standards in Japan during 1990-1991, the period of A's treatment at Y hospital.

- The dissenting justice contended that the High Court had failed to adequately define these contemporaneous medical standards, particularly by not giving sufficient consideration to relevant guidelines such as the "Manual for Terminal Cancer Care" issued in 1989 by the Ministry of Health and Welfare and the Japan Medical Association. This manual detailed specific conditions under which cancer disclosure was deemed appropriate, emphasizing factors like the patient's and family's capacity to accept the news, the quality of the doctor-patient relationship, and the availability of post-disclosure support.

- The failure to thoroughly analyze these standards was seen as a misinterpretation of a significant legal question, necessitating a re-examination by the lower court.

Analysis and Significance

This Supreme Court decision was highly significant, particularly in the context of medical practices and patient rights in Japan at the time.

- Prevailing Medical Paternalism: The legal commentary accompanying the case notes that in the early 1990s, while concepts of informed consent and patient self-determination were gaining traction in Japan, a degree of medical paternalism was still common. It was not unusual for physicians, often with benevolent intentions, to withhold a cancer diagnosis from the patient, believing it would cause undue distress. Instead, a less alarming diagnosis might be communicated. The 1989 "Manual for Terminal Cancer Care" reflected this cautious approach, suggesting that disclosure to the patient should only occur if certain preconditions were met. Indeed, in this case and another Supreme Court decision from 1995, the courts recognized that a physician's decision not to directly inform a patient of a cancer diagnosis was not, in itself, illegal under the prevailing standards of reasonable medical discretion at that time.

- Establishment of a Duty to Inform Family: Against this backdrop, the 2002 Supreme Court ruling was pioneering in establishing an ancillary duty to inform the patient's family when a decision is made not to inform the terminally ill patient directly. The Court's rationale—that such disclosure serves the patient's own legally protected interest in receiving family support and care for a better quality of remaining life—was a key development.

- Uncertainty on "Family Search" Scope: The majority opinion did not delineate the precise extent of a physician's obligation to locate or contact family members, leaving some ambiguity on how proactive such efforts must be.

- Evolution of Disclosure Norms: It is crucial to understand that medical disclosure practices in Japan have evolved considerably since the events of this case. As the commentary points out, by the time of its writing, direct disclosure of a cancer diagnosis to the patient had become the overwhelming norm (a National Cancer Center Japan survey for 2020 showed a patient notification rate of approximately 96%). Cancer is increasingly viewed not as an automatic death sentence but as a disease with many treatable forms and improving survival rates. Consequently, the traditional "therapeutic privilege" argument for withholding a diagnosis from the patient has largely lost its societal and medical backing. National policies, such as the "Basic Plan to Promote Cancer Control Programs" (2018 revision), now operate on the premise that patients will be informed.

- Enduring Relevance: Despite the shift towards direct patient disclosure, the principles established in this case regarding communication with the family may still hold relevance in specific situations, for instance, if a patient with a very poor prognosis explicitly requests not to be informed, or lacks capacity. The judgment underscores the importance of considering family involvement when direct patient communication is deemed inappropriate or insufficient. The focus of medical litigation in this area is also likely to shift from whether a diagnosis was disclosed to how adequately the prognosis, treatment options, and their implications were explained.

- Contrast with Patient-Informed Scenarios: The commentary draws a distinction by referencing a Nagoya District Court ruling where, if a patient is fully informed and subsequently refuses the recommended optimal treatment, the physician generally has no further duty to inform the family against the patient's wishes. This highlights the primacy of patient autonomy once informed consent is properly obtained, contrasting with the current case where the patient was kept unaware.

Concluding Thoughts

The 2002 Supreme Court decision reflects a transitional period in Japanese medical ethics and law, moving towards greater transparency and recognition of patient interests in end-of-life care. While direct patient disclosure is now standard, this ruling serves as an important reminder of the medical profession's responsibilities to ensure that patients, through direct communication or, in specific and limited circumstances, through their families, are afforded the support and consideration necessary for a dignified and meaningful quality of life, especially when facing a terminal illness. The case underscores the enduring importance of compassionate and comprehensive communication in medical practice.