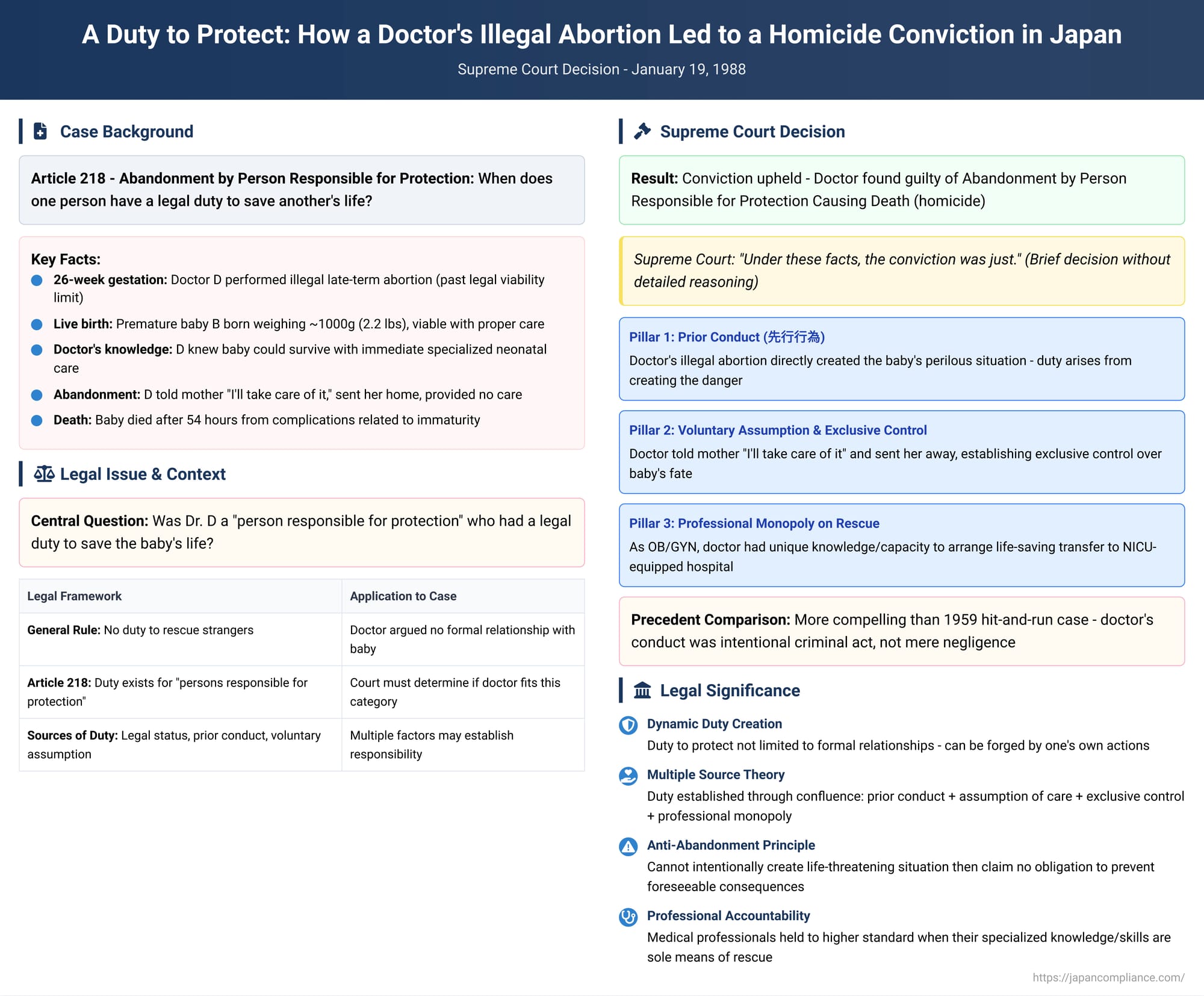

A Duty to Protect: How a Doctor's Illegal Abortion Led to a Homicide Conviction in Japan

Case Title: Case of Professional Abortion, Abandonment by a Person Responsible for Protection Causing Death, and Abandonment of a Corpse

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Decision Date: January 19, 1988

Introduction

Under what circumstances does one person have an affirmative legal duty to save another's life? While the law does not generally punish bystanders for failing to act, this principle shifts dramatically when a pre-existing responsibility exists. In Japan, this is governed by the crime of "Abandonment by a Person Responsible for Protection" (hogo sekininsha iki zai, Article 218 of the Penal Code). But what forges this "responsibility"? Is it only formal relationships like that of a parent and child, or can one's own actions in the moment create a binding legal duty to protect?

In a landmark 1988 decision, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed this profound question in a tragic and disturbing case. It involved an OB/GYN doctor who, after performing an illegal late-term abortion that resulted in a live birth, left the viable newborn to die. The Court's finding that the doctor was, in fact, a "person responsible for protection" and was therefore guilty of homicide by abandonment, provides a powerful exploration of how a duty to act is created through prior conduct, the assumption of care, and the establishment of exclusive control.

The Facts: A Life Created and Abandoned

The case centered on the actions of an OB/GYN doctor, D, who ran his own private clinic. A woman, A, requested that D perform an abortion. At the time of the procedure, the fetus was at 26 weeks gestation. Under the governing law at the time, this was past the legal limit for abortion, as a fetus at this stage was considered viable—that is, capable of sustaining life outside the womb.

D proceeded with the illegal abortion in his clinic, which resulted in the live birth of a premature baby, B, weighing just under 1,000 grams (about 2.2 pounds). D, as a medical professional, recognized that the baby had a chance of survival if it received immediate, specialized neonatal care in a properly equipped hospital. He also knew that his own clinic was completely unequipped for such care, lacking even a basic incubator. Further, D was aware that he could have quickly and easily arranged for the baby's transfer to a suitable medical facility.

Instead of taking these life-saving steps, D told the mother, A, that he would take care of the baby and instructed her to go home. After A departed, D placed the newborn baby, B, under his own management but provided no care whatsoever. He simply left the baby unattended in his unequipped clinic. Approximately 54 hours after birth, B died from complications related to immaturity.

The Supreme Court's Terse Ruling

The lower courts found D guilty not only of performing an illegal abortion but also of Abandonment by a Person Responsible for Protection Causing Death—a form of homicide. The case was appealed to the Supreme Court, which upheld the conviction.

The Supreme Court’s decision, however, was remarkably brief. After summarizing the facts—the illegal abortion, the baby's viability, the doctor's knowledge of how to save it, and his failure to do so—the Court simply concluded that "under these facts," the conviction was "just." The ruling did not explicitly detail which specific facts or legal principles were the basis for finding that Dr. D was a "person responsible for protection." This judicial minimalism left legal scholars and lower courts to unpack the profound implications of its decision.

Unpacking the Duty: The Sources of Responsibility

The core of the case lies in identifying the source of Dr. D's duty to protect baby B. Legal analysis reveals that this duty was not based on a single factor but was forged by a powerful combination of his actions, his status, and the circumstances he created.

Pillar 1: Prior Conduct (Senkō Kōi)

A cornerstone principle in the law of omissions is that a person who, through their own prior conduct, creates a situation of peril for another incurs a legal duty to act to prevent harm. Dr. D’s actions are a textbook example of this principle. His decision to perform an illegal, late-term abortion was the direct and singular cause of the helpless baby's perilous situation. Unlike a naturally occurring premature birth, this was a danger created entirely by D's intentional, criminal act. This prior conduct is widely seen as the primary source of his duty to protect the life he had brought into the world in such a vulnerable state.

Pillar 2: Voluntary Assumption of Care and Exclusive Control

A duty to act can also be created when a person voluntarily undertakes to provide care, especially when doing so deters others from rendering aid. Dr. D's statement to the mother that he would "take care of" the baby and his instruction for her to leave constituted a clear, fact-based undertaking of care.

This act had a critical dual effect. First, it was a voluntary assumption of responsibility for the baby's welfare. Second, and more importantly, it established D's exclusive control over the baby's fate. By sending the mother home, D intentionally removed the only other person who could have sought help for the baby. This act of exclusion placed the baby in a situation where its survival depended solely and exclusively on Dr. D. This creation of a situation of exclusive dependency is a powerful factor in establishing a duty to protect.

Pillar 3: Professional Status and Monopoly on Rescue

Beyond these two pillars, D's professional status created another layer of responsibility. The "protection" required in this case was not simple care; it was highly specialized medical intervention—namely, arranging a transfer to a hospital with a neonatal intensive care unit.

- As an OB/GYN, Dr. D possessed the unique knowledge and capacity to execute this rescue "quickly and easily."

- The mother, A, who was only 16 years old, lacked the specialized knowledge and capacity to arrange for this level of care herself.

This imbalance of knowledge and ability meant that Dr. D held a "monopolistic position" over the baby's chances of survival. Even before he sent the mother home, his status as the only person capable of providing the necessary rescue effectively placed him in the position of a protector. He created a peril that only he was equipped to solve, thereby solidifying his duty to do so.

Comparison to Precedent: The 1959 Hit-and-Run Case

To understand the weight of these principles, it is helpful to compare this case to a famous 1959 Supreme Court decision involving a hit-and-run driver. In that case, a driver negligently struck a pedestrian, causing serious injuries. Instead of seeking help at the scene, where hospitals were nearby, the driver put the victim in his car and abandoned him in a remote area. While the court in 1959 based the driver's duty to act on a specific traffic law, legal scholars have long argued that the duty truly arose from the driver's prior conduct (causing the accident) and his establishment of exclusive control (placing the victim in the car and driving away, preventing others from helping).

The 1988 doctor case presents an even more compelling scenario for finding a duty. The doctor's prior conduct was an intentional criminal act, not merely negligent. And his establishment of exclusive control was absolute, as he removed the baby's mother, the only other potential rescuer, from the scene.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1988 decision, though brief in its text, is a profound statement on the nature of legal responsibility. It teaches that a duty to protect is not a static concept limited to formal relationships but can be dynamically forged by an individual's own actions. The ruling demonstrates that a duty to save a life can arise from a confluence of factors: creating the danger through one's own prior conduct; voluntarily assuming responsibility for care; establishing exclusive control over the victim's fate; and occupying a unique position or possessing a monopoly on the ability to rescue. The case serves as a powerful affirmation that a person cannot intentionally create a life-threatening situation and then claim to have no obligation to prevent the tragic, and foreseeable, consequences.