A Duty to Act: Japanese Supreme Court Holds Official Criminally Liable for Omission in HIV-Tainted Blood Scandal

Decision Date: March 3, 2008, Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench (Heisei 17 (A) No. 947)

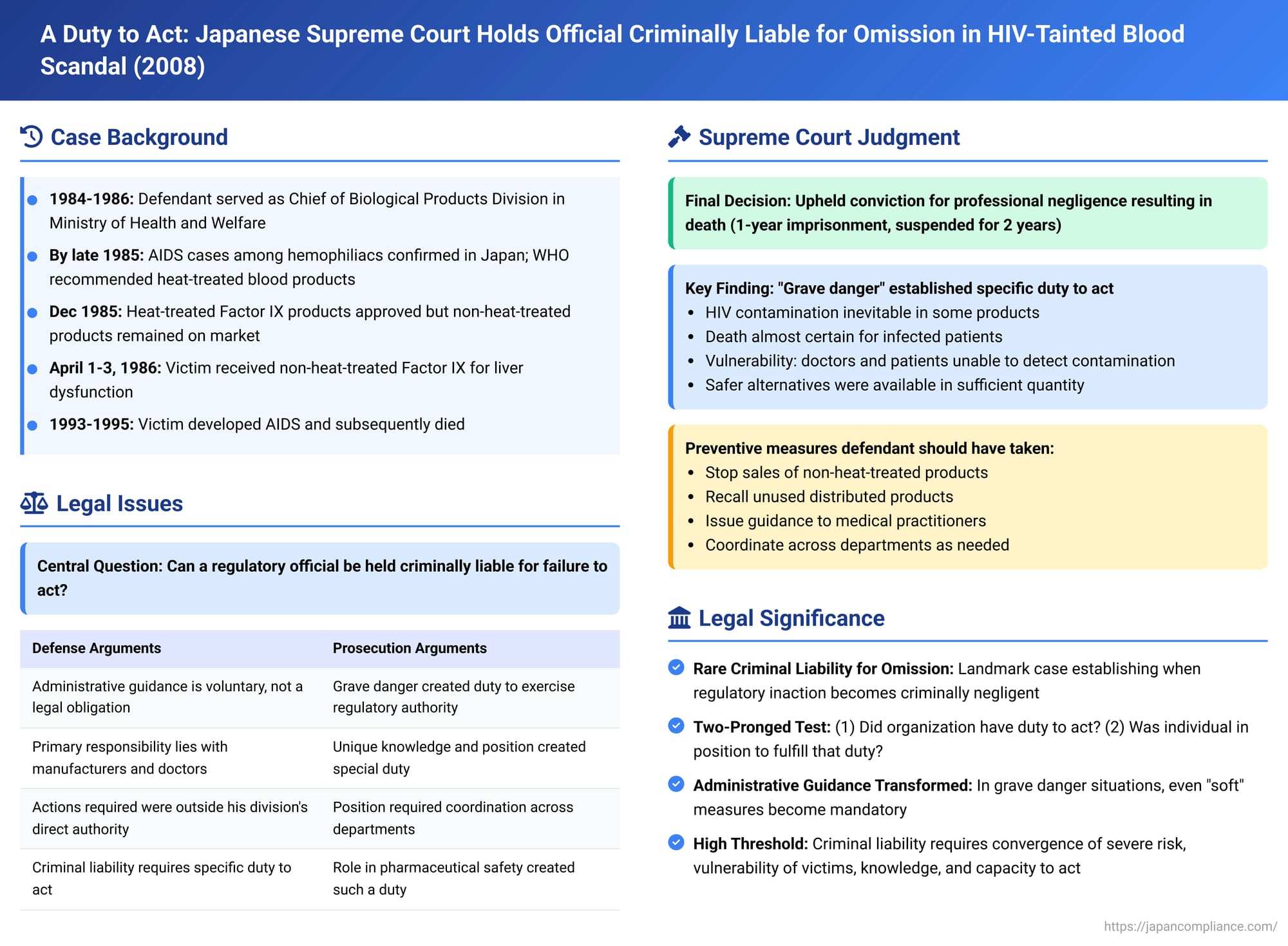

In a landmark decision with significant implications for public officials and regulatory bodies, the Supreme Court of Japan on March 3, 2008, upheld a conviction against a former senior official of the Ministry of Health and Welfare (MHW) for professional negligence resulting in death. The case centered on the official's failure to act decisively to prevent HIV infections caused by contaminated blood products during the 1980s. This ruling underscores the potential for criminal liability to arise from omissions in duty, particularly when public safety is at grave risk.

Case Background: The Defendant and the Dawning Crisis

The defendant served as the Chief of the Biological Products Division within the MHW's Pharmaceutical Affairs Bureau from July 16, 1984, to June 29, 1986. In this capacity, he was responsible for overseeing the licensing, approval, testing, and inspection of biological products, including blood derivatives. His role inherently included a duty to ensure the safety of these products and prevent harm to the public.

The legal framework governing these responsibilities was the Pharmaceutical Affairs Law. Notably, this law had been amended following prior drug-induced tragedies (such as thalidomide and SMON disease), granting the MHW Minister powers to order recalls and issue emergency directives to prevent harm from medicinal products.

Hemophilia, a genetic disorder impairing blood clotting, was commonly treated with concentrated blood coagulation factor preparations (Factor VIII for Hemophilia A, Factor IX for Hemophilia B). These products, often derived from pooled plasma sourced internationally, became a vector for HIV transmission. Non-heat-treated Factor IX products were also used for acquired clotting factor deficiencies, such as those seen in patients with liver dysfunction.

This case specifically involved a victim, V2, who suffered from liver dysfunction. Between April 1 and April 3, 1986, V2 was administered a non-heat-treated Factor IX product, manufactured by company C, at D Hospital in Osaka. V2 was subsequently infected with HIV, developed Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) by September 1993, and passed away in December 1995 at the same hospital.

Growing Awareness and the Foreseeability of Harm

By the mid-1980s, the global and domestic understanding of AIDS was rapidly evolving:

- AIDS was identified as a new, fatal disease in the United States in 1982, with cases escalating. A link to blood products was suspected, and HIV was later identified as the causative virus.

- In Japan, awareness grew of the high rate of HIV infection among hemophiliacs.

- In March 1985, news broke of two AIDS patients among hemophiliacs at a Tokyo hospital.

- The MHW's own AIDS Investigation Committee officially recognized three hemophiliac AIDS patients by May 1985 (two of whom were the aforementioned cases) and two more by July 1985. Four of these five individuals had already died.

International and domestic calls for safer products intensified:

- On April 19, 1985, following an international AIDS conference in Atlanta, Georgia (attended by Japanese medical experts, including representatives from the MHW's AIDS Investigation Committee and the National Institute of Health), the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended that only heat-treated or otherwise virus-inactivated blood coagulation factor concentrates be used for hemophiliacs. This recommendation was reported in Japanese medical journals by June 1985.

- In late 1985, the MHW's Pharmaceutical Affairs Bureau Director repeatedly stated in the National Diet (Japan's parliament) that the ministry was prioritizing the review of heat-treated Factor IX products, expected approval by year-end, and believed that blood products for hemophiliacs would then be largely safe.

- Crucially, in December 1985, internal MHW advisory bodies – the Blood Products Special Subcommittee's Blood Products Investigation Committee (December 19) and the Blood Products Special Subcommittee itself (December 26) – voiced strong opinions. Members urged that once heat-treated products were approved, the MHW should guide against the use of non-heat-treated versions. The minutes, reflecting these views (e.g., "non-heat-treated products should be promptly delisted or withdrawn from approval, and companies only having non-heat-treated products should be guided to develop heat-treated ones urgently"), were circulated to the defendant.

Based on these developments, the courts found that by the end of 1985, the defendant could clearly foresee the risk that continued administration of existing non-heat-treated products could infect HIV-negative patients, leading to AIDS and death.

Availability of Safer Alternatives and the Possibility of Averting Harm

The MHW, under the defendant's divisional leadership, had already taken steps towards safer products:

- The defendant had indicated a policy for early approval of heat-treated Factor VIII products around March/April 1985, leading to approvals for five pharmaceutical companies in July 1985.

- Similarly, in July 1985, he indicated a policy to expedite the approval of heat-treated Factor IX products. This resulted in import approvals for K Corp and C Corp in December 1985, with sales commencing by January 1986.

Furthermore, by this time:

- Other Factor IX products considered safer existed: those made exclusively from domestic Japanese plasma (believed to be free of HIV contamination at the time) and those subjected to an ethanol treatment process reported to have HIV-inactivating effects.

- Collectively, these heat-treated and other safer Factor IX options (referred to as "the subject heat-treated products, etc.") were available in sufficient quantity nationwide to meet the demand for Factor IX replacement therapy by the time V2 was treated.

- Both K Corp and C Corp could supply quantities of their new heat-treated Factor IX products that exceeded their previous sales volumes of non-heat-treated versions.

- For patients with liver dysfunction like V2, alternative medical treatments that did not involve Factor IX administration were also available.

The lower courts determined that the defendant knew, or could easily have known, of these circumstances regarding the availability of safer alternatives.

The Charge of Negligence: Lower Court Findings

The first instance and appellate courts concluded that given the foreseeability of death and the availability of means to avoid it, the defendant had a professional duty of care. Specifically, once heat-treated Factor IX products from K Corp and C Corp became available (by January 1986), he was obligated to:

- Formulate a plan, consulting with other relevant MHW departments and urging them to exercise their authority if necessary.

- Ensure that K Corp and C Corp immediately ceased sales of their non-heat-treated Factor IX products.

- Have these companies recall their unused, distributed non-heat-treated Factor IX as quickly as possible, replacing them with their heat-treated counterparts.

- Take measures to ensure that physicians refrained from any non-urgent or unnecessary administration of the risky non-heat-treated Factor IX products.

The courts found that the defendant negligently failed to fulfill this duty. Instead, he left the handling of non-heat-treated products to the discretion of pharmaceutical companies and others, effectively permitting their continued sale and use. This inaction, they ruled, directly led to the death of V2. He was sentenced to one year of imprisonment, suspended for two years.

The Supreme Court's Deliberation and Ruling

The defendant appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing, inter alia, that:

- Administrative guidance is, by nature, a request for voluntary action and cannot be construed as a legal obligation upon a public servant.

- The primary responsibility for preventing harm from pharmaceuticals lies with the manufacturers and prescribing physicians, with the MHW holding a secondary, supervisory role.

- The exercise of MHW's authority is bound by legal prerequisites.

- Criminal liability for an individual public official requires a strong, specific duty to act, which was absent in his case.

- The actions he was supposedly obligated to take were outside the specific jurisdiction of his Biological Products Division.

The Supreme Court, in its March 3, 2008 decision, dismissed the appeal and upheld the conviction. While acknowledging some of the defense's general points, the Court found them insufficient to negate criminal liability under the specific, grave circumstances of this case.

The Court's Reasoning:

- Acknowledging General Principles, but Highlighting Specific Dangers:

The Court concurred that administrative guidance itself does not typically constitute a legally binding obligation on an official, and that primary responsibility for drug safety usually rests with companies and doctors. It also agreed that an official's inaction, while potentially leading to disciplinary action or state liability in tort, does not automatically translate into individual criminal responsibility.However, the Court emphasized the extraordinary context:- High Risk and Inevitability of Death: The non-heat-treated products were widely used, a significant portion were contaminated with HIV. Medical understanding at the time, even if incomplete, clearly indicated that using these products could lead to HIV infection and subsequently AIDS. Once AIDS developed, there was no effective treatment, and death was a highly probable, almost inevitable outcome for many.

- Vulnerability of Users: Awareness of the product's danger was not necessarily shared among all relevant parties. Critically, it was impossible for doctors or patients to discern whether a specific batch of the product was HIV-contaminated. This made it practically impossible for them to avoid the risk of HIV infection through their own diligence.

- State Approval and the Need for Decisive State Action: These products were on the market due to state approval. Given their inherent danger, their sale and use should ideally have been halted or, at a minimum, strictly limited to medically indispensable situations. The Court recognized a concrete risk: if the MHW failed to provide clear directives, indiscriminate or opportunistic sales and use would likely continue, especially considering past behaviors where reliance on pharmaceutical companies' self-regulation had proven insufficient.

- Existence of a "Grave Danger" and the Basis for Compulsory Powers:

The Supreme Court found that these circumstances constituted a "grave danger." This finding was pivotal because it established the prerequisite for the Minister of Health and Welfare to exercise various compulsory supervisory powers granted under the Pharmaceutical Affairs Law, such as Article 69-2 (emergency orders to prevent public health hazards). - Emergence of a Specific Duty to Act (Administrative and Criminal):

The existence of this "grave danger" and the potential to use compulsory powers meant that a specific duty arose for the MHW to take necessary and sufficient measures to prevent harm. This duty was not merely administrative; the Court held that it extended to a criminal law duty of care for those individuals within the MHW responsible for pharmaceutical administration concerning the manufacturing, use, and safety assurance of the implicated products. They were deemed to be engaged in業務 (gyomu – professional activities) related to preventing harm from pharmaceuticals in social life, thus incurring a duty of care under criminal law. - Scope of Necessary Preventive Measures:

The Court clarified that the required preventive measures were not limited to legally compulsory actions. If the objective of preventing harm could be reasonably achieved through measures encouraging voluntary compliance (whether termed "administrative guidance" or otherwise), such actions were also encompassed within this duty. Given the MHW's supervisory authority over pharmaceutical companies, such measures were considered a rational component of the overall preventive strategy. - The Defendant's Central Role and Personal Responsibility:

The Supreme Court affirmed the defendant's pivotal position. The non-heat-treated blood products linked to AIDS fell directly under the jurisdiction of his Biological Products Division. Consequently, he was a central figure within the MHW concerning AIDS countermeasures related to these products. He had a duty to assist the Minister and to integrally execute pharmaceutical administration aimed at preventing harm.

This duty explicitly included liaising with other MHW bureaus or departments as needed and urging them to take necessary actions. The Court found no significant legal or factual impediments that would have made it impossible or unreasonably difficult for the defendant to take the kinds of measures identified by the lower courts (such as ordering sales to stop and recalls, and issuing guidance to medical practitioners).Crucially, the Supreme Court stated: "While it goes without saying that the victim's death in this case should not be attributed exclusively to the defendant's responsibility, the defendant cannot escape his responsibility." This acknowledged that multiple parties might bear responsibility but unequivocally affirmed the defendant's culpable role.

The Supreme Court thus found the lower courts' determination of negligence to be justifiable and upheld the guilty verdict.

Significance of the Ruling

This 2008 Supreme Court decision is highly significant in Japanese law for several reasons:

- Criminal Liability for Omission by a Bureaucrat: It is a rare, if not unique, instance of Japan's highest court affirming the criminal liability of a regulatory official for a failure to act (an omission) in the context of a public health crisis, rather than for a direct commission of a harmful act.

- Defining the Duty to Act for Officials: The case elaborates on the conditions under which a general supervisory responsibility of a public official can transform into a specific, legally enforceable duty to act, the breach of which can attract criminal penalties. The "grave danger" to public health and the availability of statutory powers to mitigate that danger were key to this transformation.

- Two-Pronged Test for Organizational Liability: The decision implicitly supports a two-pronged approach to an individual's duty to act within an organization:

- Did the organization itself (here, the MHW) have a duty to act to prevent the harm?

- Was the specific individual in a position within the organization to take or initiate measures to fulfill that duty?

The Supreme Court affirmed both aspects in this case. The MHW's duty arose from its statutory supervisory powers, its prior act of approving the drugs (which created a form of public assurance and subsequent responsibility when danger became known), and its superior access to information about the risks when physicians and patients were largely uninformed. These elements align with generally recognized legal grounds for establishing a duty to act, such as legal obligation, prior conduct creating risk, and exclusive control or knowledge.

- Status of Administrative Guidance: While administrative guidance is generally non-compulsory, this ruling suggests that in situations where severe compulsory measures are justified, the failure to take even "softer" measures like issuing strong guidance or urging voluntary recalls can contribute to a finding of criminal negligence if such measures could have reasonably mitigated the harm.

- The "Unprecedented Situation" Threshold: The judgment underscores that the threshold for imposing criminal liability for an official's inaction is exceptionally high. It was the convergence of several factors—the severity of the risk (inevitable death for many), the vulnerability of the victims, the defendant's knowledge and capacity to act, and the sheer scale of the potential harm if the state failed to intervene—that elevated the defendant's professional responsibilities to the level of a criminal duty of care.

Commentators have noted the potential harshness of holding a mid-level official criminally liable for failing to orchestrate measures that were, in some respects, unprecedented and reliant on cooperation from other governmental departments and industry. However, the courts ultimately found that the catastrophic nature of the unfolding AIDS crisis, directly linked to state-approved products, necessitated such proactive intervention by those in positions of authority.

This case serves as a stark reminder of the profound responsibilities that can attach to public office, especially in matters of public health and safety, and the potential for severe legal consequences when those responsibilities are not met in the face of foreseeable and preventable harm.