A Doctor's Duty: Reporting "Unusual Deaths" vs. Self-Incrimination in Japan

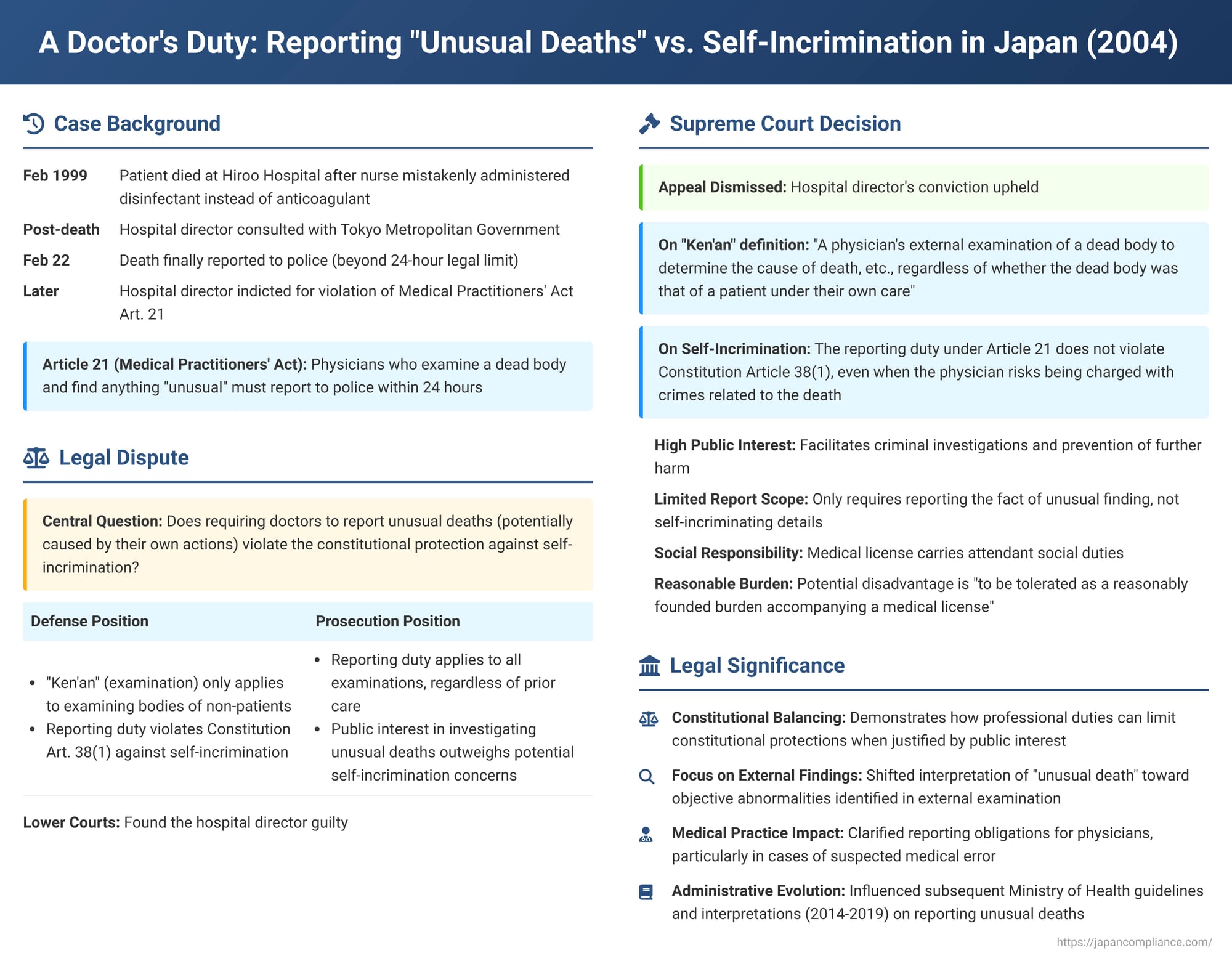

Physicians often face profound ethical and legal responsibilities, particularly when a patient's death occurs under unusual circumstances. In Japan, Article 21 of the Medical Practitioners' Act mandates that a physician who conducts an external examination (ken'an) of a dead body and finds anything "unusual" (ijō) must report it to the police within 24 hours. But what if the physician themself might be implicated in the death, perhaps due to a medical error? Does this reporting duty infringe upon their constitutional right against self-incrimination? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this critical issue in a judgment on April 13, 2004 (Heisei 15 (A) No. 1560).

The Hiroo Hospital Case: A Tragic Mix-Up and a Reporting Delay

The case stemmed from a tragic incident at Hiroo Metropolitan Hospital in Tokyo. In February 1999, Patient A, who had undergone hand surgery, died after a nurse mistakenly administered a disinfectant solution (Hibitane Gluconate) instead of an anticoagulant (Heparin Sodium saline solution). A subsequent pathological autopsy indicated that the incorrect administration likely led to fatal acute pulmonary thromboembolism.

The defendant in this case was the hospital director. Initially, a day after the incident, he considered reporting the death to the police. However, after consulting with the Tokyo Metropolitan Government (the hospital's supervisory authority), which expressed a reluctant view, the director delayed the official report until February 22, well beyond the 24-hour limit stipulated by Article 21.

The hospital director, along with the attending physician B (who had performed CPR on Patient A) and a Tokyo Metropolitan official C, were indicted as co-principals for violating Article 21 of the Medical Practitioners' Act (failure to report an unusual death), as well as for related offenses such as creating and using false official documents. Physician B did not contest the charges and was summarily convicted and fined. Official C was acquitted due to lack of intent as a co-principal. The hospital director, however, fought the charges up to the Supreme Court.

The lower courts found the hospital director guilty. The High Court, while adjusting the precise timing of when Physician B was deemed to have recognized the death as "unusual" (pinpointing it to observations made during the pathological autopsy on February 12), ultimately upheld the director's conviction as a co-conspirator in the delayed reporting. The High Court defined "ken'an" under Article 21 as "a physician's external examination of a dead body to determine the cause of death, regardless of whether the deceased was a patient under their care." It also rejected the director's arguments that applying this reporting duty in cases involving a physician's own patient, especially where medical error might be suspected, violated constitutional principles like legality or the privilege against self-incrimination.

The Legal Questions Before the Supreme Court

The hospital director's appeal to the Supreme Court centered on two main arguments:

- The meaning of "ken'an" (external examination/autopsy): The defense argued that "ken'an" in Article 21 should only refer to an initial examination of a deceased person by a physician who had not been treating that person. Examining one's own deceased patient, they contended, did not fall under this definition.

- Violation of the privilege against self-incrimination (Constitution Article 38, Paragraph 1): The defense asserted that requiring a physician to report an "unusual death" under Article 21, especially when the physician themselves could face criminal charges (e.g., professional negligence causing death) related to that death, was unconstitutional.

The Supreme Court's Ruling (April 13, 2004): Duty Upheld, Definition Clarified

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal, upholding the hospital director's conviction.

1. "Ken'an" Defined Broadly:

The Court clarified the scope of "ken'an": "Ken'an of a dead body under Article 21 of the Medical Practitioners' Act means a physician's external examination of a dead body to determine the cause of death, etc., and it is appropriate to interpret this as applying regardless of whether the said dead body was that of a patient under their own care. The original judgment [High Court], which is to the same effect, can be affirmed as correct." This confirmed that the duty applies even when a doctor is examining a patient they had been treating.

2. Reporting Duty and Self-Incrimination: No Constitutional Violation:

The Court extensively addressed the constitutional challenge:

- Public Interest Served: The reporting duty under Article 21 serves significant public interests. It facilitates criminal investigations by providing police with initial leads and enables authorities to take prompt action to prevent further harm or danger, thus contributing to societal defense. The necessity of this duty is high, as unusual deaths can be linked to serious crimes.

- Nature of the Report: The constitutional privilege against self-incrimination (Article 38, Paragraph 1) protects individuals from being compelled to provide testimony on matters that could lead to their own criminal liability. However, the duty under Article 21 merely requires a physician who has examined a dead body and found something unusual in its condition (regarding the cause of death, etc.) to report that fact to the police. It "does not compel the disclosure of the reporter's involvement with the dead body or other matters constituting a criminal act."

- Physician's Social Responsibility: A medical license not only grants the qualification to perform medical acts that directly affect human life but also entails "attendant social responsibilities."

- Permissible Burden: The Court concluded that even if fulfilling this reporting obligation might indirectly provide an opening for investigative authorities to discover a physician's own potential crime, this "potential disadvantage is to be tolerated as a reasonably founded burden accompanying a medical license," considering the nature, content, and extent of the reporting duty, the special character of a medical license, and the aforementioned high public necessity for such reporting.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court held that requiring a physician who has found an abnormality upon examining a dead body to report it under Article 21, "even in cases where the physician themselves may risk being charged with crimes such as professional negligence causing death related to the said cause of death, etc., does not violate Article 38, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution."

The Crux: What Makes a Death "Unusual" for Reporting Purposes?

While the Supreme Court's judgment focused on the definition of "ken'an" and the self-incrimination issue, a critical underlying aspect is the interpretation of what constitutes an "unusual" (ijō) death triggering the reporting duty.

- Focus on External Examination Findings: The Supreme Court's definition of "ken'an" as an "external examination of a dead body to determine the cause of death, etc.," and its reasoning that the report does not compel disclosure of "the reporter's involvement with the dead body or other matters constituting a criminal act," strongly suggest that the primary trigger for the reporting obligation is an objectively observable "unusual" finding during the external examination of the body itself.

- Evolution of Interpretation and Subsequent Clarifications:

- Historically, Article 21, which has roots in Meiji-era legislation, was likely aimed at uncovering general criminal activity, rather than specifically addressing deaths arising from medical error.

- Over time, particularly from the mid-1990s, guidelines from bodies like the Japan Society of Legal Medicine and administrative manuals from the Ministry of Health broadened the concept of "unusual death." These interpretations sometimes included any unexpected death related to medical acts or any death not clearly attributable to a diagnosed and treated natural illness. This broader interpretation led to confusion within the medical community and a significant increase in reports of medical incidents to the police, especially after the first instance court delivered a guilty verdict in this very case.

- The PDF commentary highlights that although this 2004 Supreme Court judgment garnered attention for its stance on self-incrimination, its more crucial impact, particularly in subsequent administrative practice, has been the emphasis on external findings from the ken'an as the basis for the Article 21 report.

- In 2014, the then-Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare explicitly stated, referencing this Supreme Court decision, that the reporting duty applies "when a doctor, upon externally examining a dead body, judges that there is an abnormality." Following this, the 2015 edition of the official Death Certificate (Post-mortem Examination Certificate) Manual removed its previous reference to the broader Japan Society of Legal Medicine guidelines.

- Although a 2019 Ministry of Health notice briefly seemed to revert to a wider interpretation (considering circumstances beyond just external findings), it was quickly followed by an addendum to the 2019 Manual. This addendum explicitly stated that the notice did not alter the interpretation established by the Supreme Court's 2004 ruling and reiterated the Health Minister's 2014 statement focusing on external examination findings.

- Thus, the prevailing practical understanding, shaped significantly by this Supreme Court judgment and subsequent administrative clarifications, is that the Article 21 reporting duty for "unusual deaths" is primarily triggered by abnormalities identified during the physician's external examination of the deceased's body.

- Ongoing Debate: Despite this trend towards focusing on external findings, some legal and medical commentators criticize this as potentially too restrictive, arguing that a proper assessment of whether a death is "unusual" might necessitate considering information beyond purely external bodily conditions.

Implications for Medical Professionals

This Supreme Court decision has several key implications for physicians in Japan:

- It confirms a broad obligation to perform a "ken'an" (external examination for cause of death) and report objectively identified external unusual conditions, even for patients who were under their own care.

- While the report itself is limited to the factual finding of an abnormality, the act of reporting can, as the Court acknowledged, become a starting point for further investigation.

- The legal landscape surrounding the reporting of medical errors remains complex. The Article 21 duty exists alongside other potential reporting mechanisms, such as internal hospital incident reviews and, more recently, a dedicated medical accident investigation system. The interplay between these systems continues to be a subject of discussion.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's 2004 decision in the Hiroo Hospital case affirmed the physician's statutory duty under Article 21 of the Medical Practitioners' Act to report "unusual deaths," even when doing so might potentially lead to self-incrimination. The Court achieved this by narrowly defining the scope of the required report (focusing on the fact of an unusual finding upon examination) and by framing the duty as a reasonable societal burden accompanying a medical license. Crucially, the ruling, along with subsequent administrative developments, has steered the practical interpretation of this duty towards being primarily triggered by abnormalities identified during the external examination of the deceased's body. This judgment highlights the ongoing tension between public safety imperatives, such as the need for effective criminal investigation, and the constitutional rights of individuals, particularly professionals like physicians who operate under unique legal and ethical responsibilities.