A Divorce on Paper Only? Japan's Supreme Court on 'Divorces of Convenience' and the Intent to End a Legal Marriage

Date of Judgment: March 26, 1982

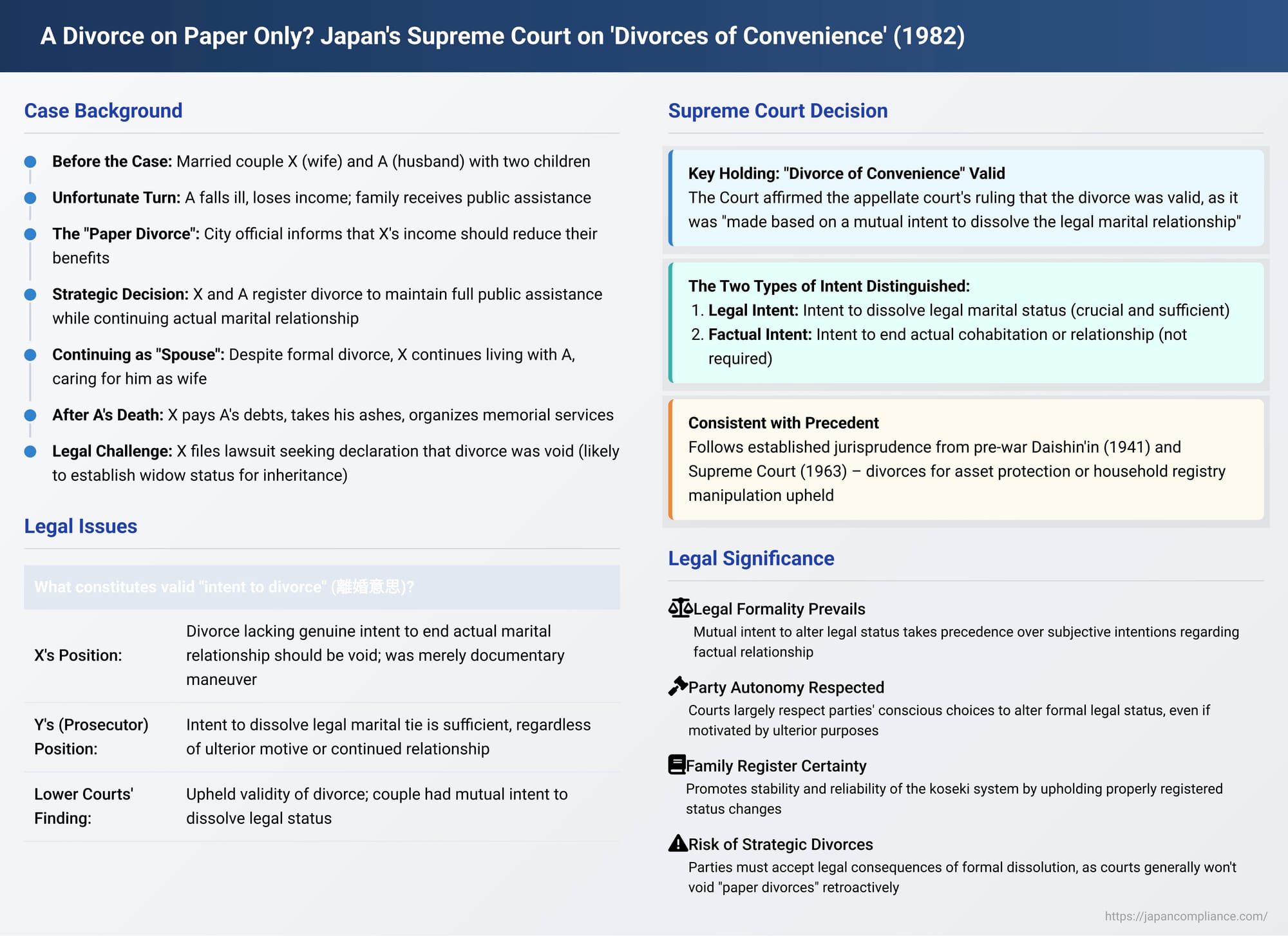

In Japan, divorce by mutual agreement (協議離婚 - kyōgi rikon) is a relatively straightforward process, primarily requiring the submission of a divorce notification signed by both spouses and adult witnesses. This accessibility, however, sometimes leads to situations where couples register a divorce not out of a genuine desire to terminate their entire relationship, but as a "matter of convenience" (hōben) to achieve some other specific, often financial or administrative, objective, all while intending to continue their de facto marital life. This raises a fundamental legal question: is such a "paper divorce" valid if the underlying intent is not to truly separate but to leverage the legal status of divorce for an ulterior purpose? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this issue in a key decision on March 26, 1982 (Showa 56 (O) No. 1197), clarifying the nature of "intent to divorce" (離婚意思 - rikon ishi) required for a divorce by agreement to be legally effective.

The Facts: A Calculated Divorce for Public Assistance

The case involved a couple, X (the wife) and her husband, A. They were married and had two children. Their circumstances took a difficult turn when A fell ill and lost his income, compelling the family to rely on public assistance (生活保護 - seikatsu hogo) to cover their living expenses and A's medical costs. X also had some income of her own.

A city official informed the couple that X's income should rightfully be deducted from their public assistance payments, and that their failure to report her income meant they had been improperly receiving benefits. Faced with the prospect of having to repay previously received benefits and wanting to continue receiving the full amount of public assistance, X and A made a calculated decision: they agreed to register a divorce. This divorce was, by their own admission and the findings of the lower courts, a "matter of convenience" designed solely to navigate the public assistance rules.

Despite this formal divorce registration, X continued to live with A and care for him, considering herself to be his wife in all substantive aspects of their relationship. After A eventually passed away, X paid his outstanding debts, took possession of his ashes, and organized his memorial services—all actions typically undertaken by a surviving spouse.

Sometime after A's death, X initiated a lawsuit against Y (the Public Prosecutor, who acts as a defendant in legal actions seeking to confirm or invalidate the status of a deceased person's marriage or divorce). X sought a court declaration that the divorce she and A had registered was null and void. The underlying motivation for X's lawsuit, as suggested by Y in the initial proceedings, appeared to be to re-establish her legal status as A's widow, potentially to enable her to inherit a right A might have had to claim damages in an unrelated matter.

The Lower Courts' Position: Intent to Dissolve the Legal Tie is Sufficient

Both the Sapporo District Court and the Sapporo High Court dismissed X's claim, thereby upholding the validity of the divorce. The High Court's reasoning was direct: X and the late A, in order to use the divorce as a "convenience" for the stated purpose (related to public assistance), had submitted the divorce registration based on a mutual intent to dissolve their legal marital relationship. Therefore, the High Court concluded, a legally sufficient "intent to divorce" existed between them. Even considering the various sympathetic circumstances, the High Court found that the divorce could not be deemed void merely for lacking what might be termed a "factual" intent to separate, as long as the intent to terminate the legal status was present. X appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Upholding the "Divorce of Convenience"

The Supreme Court, in a concise judgment, affirmed the lower courts' decisions and dismissed X's appeal.

The Core Principle:

The Court endorsed the High Court's finding, stating: "Under the facts lawfully determined by the appellate court, the appellate court's judgment that the divorce registration in this case was made based on a mutual intent to dissolve the legal marital relationship, and that this divorce cannot be deemed void, is justifiable in light of its reasoning".

This ruling effectively confirmed that for a divorce by agreement to be valid in Japan, the critical element is the mutual intention of the parties to terminate their legal marital status. The underlying motives for seeking this legal dissolution, or the parties' intentions regarding the continuation of their factual cohabitation or relationship, are generally considered secondary as long as the intent to end the legal marriage itself is present.

This decision is consistent with a line of precedents dating back to the pre-war Daishin'in (Great Court of Cassation, Japan's highest court before the Supreme Court). For instance:

- A Daishin'in judgment from Showa 16 (1941) involved a couple who divorced to protect assets from execution but continued their de facto marital relationship. When the husband later attempted to marry another woman, the first wife sought to annul her "paper divorce." The court held that the parties had, at the time of the divorce, intended "at least to dissolve the legal marital relationship for the time being" even if they planned to continue as a de facto couple. The divorce was deemed valid.

- A Supreme Court judgment from Showa 38 (1963) involved a divorce and remarriage orchestrated to change the official head of a household. After the wife's death, the husband sought to annul the divorce (against the Public Prosecutor) to secure survivor benefits for his son. The Court found a "mutual intent to dissolve the legal marital relationship" and upheld the divorce's validity.

The 1982 Supreme Court decision squarely places itself within this established judicial interpretation.

Understanding "Intent to Divorce": The Distinction Between Legal and Factual Dissolution

The key to understanding this line of jurisprudence lies in the distinction the courts make between:

- Intent to dissolve the legal marital bond: This refers to the parties' understanding and agreement that by filing the divorce notification, their official status as husband and wife under the law will end. This termination carries with it the cessation of various legal rights and obligations that flow from being legally married, such as spousal inheritance rights under the statutory scheme, the legal presumption of legitimacy for children subsequently born to the wife by that husband, and certain tax or social security statuses tied to legal marriage.

- Intent to dissolve the factual marital relationship: This refers to an intention to actually cease cohabitation, emotional partnership, shared finances (beyond legal obligations), and other aspects of a shared life as a couple.

The consistent position of the Japanese Supreme Court, as reaffirmed in this 1982 case, is that for a divorce by agreement (kyōgi rikon) to be valid, only the first type of intent—the mutual will to terminate the legal marital relationship—is strictly necessary. The parties' private intentions regarding the continuation or nature of their factual relationship post-divorce do not, in themselves, invalidate a legally registered divorce if the intent to sever the legal tie was present.

Why Uphold Such Divorces of Convenience?

Several underlying reasons can be discerned for the courts' stance on upholding divorces registered for ulterior motives, provided the intent to dissolve the legal relationship exists:

- Party Autonomy in Formal Status: The Japanese system of divorce by agreement places a high value on the autonomy of the parties to formally declare and alter their legal status. If both adult parties consciously choose to terminate the legal incidents of marriage, the law generally respects that declared intention.

- Certainty and Clarity of the Family Register: The family register (koseki) system in Japan is a public record of vital legal statuses. Upholding duly registered divorces, even if the motives are questioned, maintains the clarity and reliability of this system. Allowing such divorces to be easily invalidated later based on subjective claims about "true" intentions could create significant legal instability.

- Potential for Abuse if Easily Invalidated: If "paper divorces" could be readily overturned years later by one party claiming they "didn't really mean it" in a factual sense, it could open the door to abuse or uncertainty, especially if one of the parties subsequently remarried or made significant life decisions based on their divorced status.

- Availability of Legal Protections for De Facto Relationships: While not identical to the rights of legally married spouses, Japanese law does offer certain legal protections for stable, marriage-like de facto relationships (内縁 - nai'en). Thus, the continuation of cohabitation after a "paper divorce" is not necessarily a complete legal vacuum, and the parties might acquire rights and obligations based on their nai'en status.

Academic Perspectives and Ongoing Debates

The issue of "intent" in status-creating or status-altering acts (like marriage, adoption, or divorce) has long been a subject of academic debate in Japan.

- Traditional Theories: Older debates often revolved around a "substantive intent" theory (requiring an intent to create or destroy the actual, factual substance of the relationship) versus a "formal intent" theory (where the intent to complete the legal registration was deemed sufficient). The Supreme Court's approach in "divorce of convenience" cases does not fit neatly into a purely substantive intent framework, as it upholds divorces where the factual relationship is intended to continue.

- Modern Analytical Approaches: More recent scholarship tends to analyze each type of status act (marriage, divorce, adoption) individually, considering the specific legal effects involved.

- Focus on Intended Legal Effects: One approach examines what specific legal effects the parties intended to achieve or avoid by their actions. If parties understood that filing for divorce would terminate their legal marriage and its attendant rights and duties (even if their motive was external to typical divorce reasons, such as qualifying for social benefits), then the requisite legal intent is often found to exist.

- Ex Post Facto Evaluation: Another approach involves an evaluation of the overall circumstances after the fact, considering factors such as whether the intended (ulterior) purpose of the divorce was achieved, who is challenging the divorce's validity and why, the impact on the parties (e.g., if one has since remarried or died), and the interests of any third parties involved (e.g., social security agencies that paid benefits based on the divorced status).

- Public Policy Considerations: Sometimes, the perceived impropriety of the motive behind the divorce (e.g., if it was to facilitate an illegal act or to unfairly evade legal obligations – a dappō kōi or act in circumvention of the law) or the inconsistency of a party later challenging a divorce they themselves willingly entered into for convenience (raising issues akin to the "clean hands" principle) are also discussed as relevant factors.

Distinction from "Sham Marriages"

It is generally understood that "divorces of convenience" are distinct from "sham marriages" (仮装結婚 - kasō kekkon). A sham marriage is typically one where, from the outset, there is no genuine intent by one or both parties to create any real marital bond, either legal or factual, often for a fraudulent purpose such as obtaining a visa. Such marriages might be declared void from the beginning due to a fundamental lack of marital intent. In contrast, "divorces of convenience" usually involve a pre-existing, valid marriage, and the legal question centers on the sufficiency of the intent to terminate the legal aspects of that established marriage.

Conclusion: Legal Formality Prevails in "Divorces of Convenience"

The Supreme Court of Japan's 1982 decision reaffirmed a consistent line of jurisprudence: a divorce by mutual agreement is generally considered legally valid if both parties mutually intend to dissolve their legal marital relationship, even if their primary motivation for doing so is to achieve some other objective and they intend to continue their cohabitation and factual relationship. This legal stance prioritizes the parties' formal declaration to alter their legal status over their subjective intentions regarding the continuation of their de facto life together.

While this approach provides certainty regarding legal status as reflected in official registrations, it also highlights the potential for divergence between legal formalities and the substantive realities of personal relationships. The ruling underscores that when parties choose to use the legal act of divorce as a "matter of convenience," they must generally accept the legal consequences that flow from that formal dissolution, even if their lived experience remains largely unchanged.