A 'Divorce Catch-22': Japanese Supreme Court on Jurisdiction When Foreign Decrees Aren't Recognized

Date of Judgment: June 24, 1996

Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

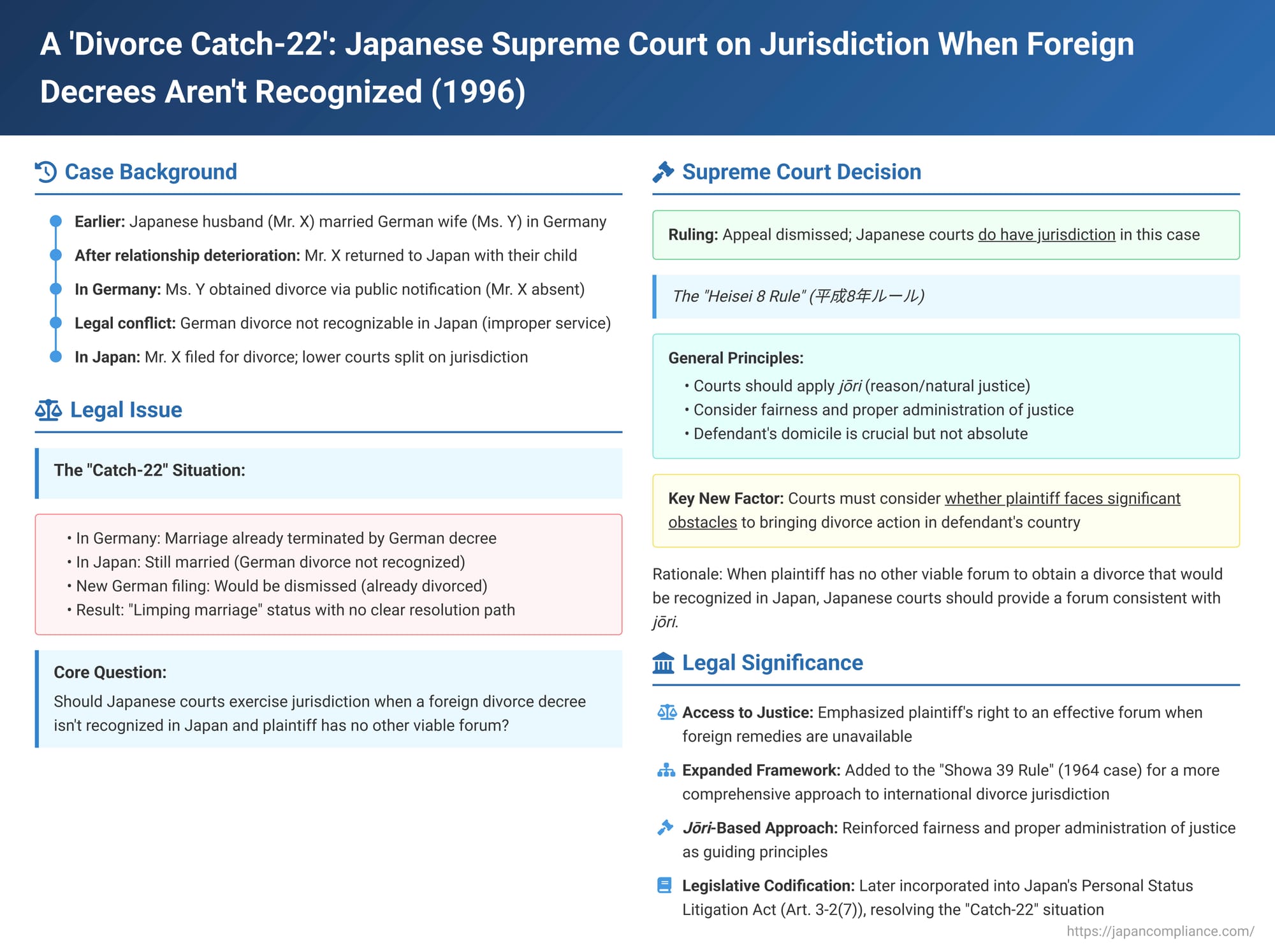

International marriages can sometimes lead to complex legal situations if they break down, especially when divorce proceedings occur in different countries. A particularly challenging scenario arises if a divorce granted in one spouse's country of residence is not recognized in the other spouse's country, potentially leaving one party considered divorced while the other is still legally married—a "limping marriage." A Japanese Supreme Court decision on June 24, 1996, often referred to as the "Heisei 8 Rule," addressed the crucial question of whether Japanese courts can exercise jurisdiction over a divorce petition when the plaintiff faces such a predicament.

The Factual Background: A German Divorce Unrecognized in Japan

The case involved a Japanese husband and a German wife:

- Mr. X (Plaintiff): A Japanese man.

- Ms. Y (Defendant): A German woman.

- The couple married in Germany and had a child, A.

- After their relationship deteriorated, Ms. Y began refusing to live with Mr. X. Mr. X subsequently returned to Japan with their child, A.

- Ms. Y initiated divorce proceedings in Germany. The German court summons and other legal documents were served on Mr. X by public notification (公示送達 - kōji sōtatsu), a method of service used when a party's whereabouts are unknown or direct service is impractical. Mr. X did not appear in the German proceedings.

- The German court granted Ms. Y's divorce petition and awarded her custody of child A. This German divorce judgment became final.

- Meanwhile, Mr. X also filed for divorce in Japan. The Urawa District Court (Koshigaya Branch) initially dismissed his suit, finding that Japanese courts lacked international adjudicatory jurisdiction. However, the Tokyo High Court, on appeal by Mr. X, reversed this dismissal. The High Court found that there was scope for Japanese courts to exercise jurisdiction and remanded the case for further proceedings. Ms. Y then appealed the High Court's decision (which affirmed potential Japanese jurisdiction) to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Dilemma: Where Can the Husband Get a Divorce Recognized in Japan?

The central problem for Mr. X was a classic "catch-22":

- Under German law, his marriage to Ms. Y was already dissolved by the final German divorce decree.

- However, this German divorce judgment was not recognizable in Japan. According to Japanese law (Article 200(ii) of the old Code of Civil Procedure, similar to Article 118(ii) of the current Code), a condition for recognizing a foreign judgment is that the losing defendant (Mr. X in the German case) must have been properly served with process or must have appeared in the proceedings. Service by public notification, particularly when the defendant's whereabouts might have been ascertainable or other service methods were possible, generally does not satisfy this requirement if the defendant did not actually appear.

- This meant that, from Japan's legal perspective, Mr. X was still married to Ms. Y.

- If Mr. X were to attempt to file a new divorce petition in Germany, it would likely be dismissed as inadmissible because, in Germany, the marriage was already considered terminated.

This left Mr. X in a "limping" marital status—divorced in Germany but still married in Japan—with seemingly no straightforward way to obtain a divorce that would be effective in Japan.

The Supreme Court's "Heisei 8 Rule" for Jurisdiction

The Supreme Court dismissed Ms. Y's appeal, thereby upholding the Tokyo High Court's decision that Japanese courts could indeed exercise jurisdiction over Mr. X's divorce petition. The Supreme Court's reasoning established what has come to be known as the "Heisei 8 Rule":

1. Reaffirmation of General Principles for International Divorce Jurisdiction:

The Court began by restating the general principles for determining international adjudicatory jurisdiction in divorce cases, which had been developing through case law since the 1960s:

- The defendant's domicile is a crucial factor. If the defendant is domiciled in Japan, Japanese courts naturally have jurisdiction.

- However, even if the defendant is not domiciled in Japan, Japanese courts may still affirm jurisdiction if the plaintiff is domiciled in Japan and other factors establish a sufficient connection between the divorce claim and Japan.

- In the absence of specific statutes or well-established international customary law directly governing international jurisdiction, such determinations should be made in accordance with "jōri" (reason, natural justice, or equity), guided by the ideals of ensuring fairness between the parties and the proper and prompt administration of justice.

2. Key Factor: Plaintiff's Inability to Effectively Sue in the Defendant's Domicile Country:

The Supreme Court then introduced a critical consideration specific to the circumstances of this case:

- When deciding on jurisdiction, courts must not only consider the potential disadvantage to a defendant forced to respond in a foreign court but also, importantly, whether the plaintiff faces significant legal or factual obstacles to bringing a divorce action in the defendant's country of domicile.

- The objective is to ensure that the plaintiff's fundamental right to seek a divorce is not unjustly denied due to a lack of an appropriate forum.

3. Application to Mr. X's Situation:

Applying this principle to the facts before it, the Supreme Court reasoned:

- While the marriage between Mr. X and Ms. Y was considered terminated in Germany due to the German divorce decree, this decree was not recognizable in Japan because of the improper service on Mr. X.

- Therefore, under Japanese law, Mr. X and Ms. Y were still married.

- If Mr. X were to attempt to sue for divorce again in Germany, his action would most likely be dismissed because German law already considered the marriage dissolved.

- This created a situation where Mr. X effectively had no viable means to obtain a divorce recognizable in Japan other than by filing suit in Japan, where he was domiciled.

- Conclusion: Given these circumstances, the Supreme Court held that affirming Japan's international adjudicatory jurisdiction over Mr. X's divorce petition was consistent with jōri (reason). It provided Mr. X with a necessary forum to address his marital status under Japanese law.

4. Distinction from the Prior "Showa 39 Rule":

The Supreme Court explicitly stated that its earlier landmark decisions on divorce jurisdiction from 1964 (the "Showa 39 Rule," which dealt with cases where the defendant was missing or had abandoned the plaintiff – see case 86 in this series) addressed different factual scenarios and were therefore "not apposite to the present case."

Significance and Impact

This 1996 "Heisei 8 Rule" decision was a significant development in Japanese private international law:

- Clarification of Jōri in Divorce Cases: It explicitly applied the broad jōri-based approach (considering fairness and the proper/prompt administration of justice) to divorce jurisdiction, reinforcing that this general principle was not confined to property-related cases but was a universal standard for determining international jurisdiction in the absence of specific rules.

- The "Plaintiff's Need for a Forum" as a Jurisdictional Factor: The ruling gave significant weight to the plaintiff's inability to obtain effective relief in the defendant's home country (or the country of the initial divorce) as a compelling reason for Japanese courts to assume jurisdiction. This addresses the problem of "denial of justice" if no other competent forum is practically available to the plaintiff.

- Relationship with the "Showa 39 Rule": Professor Hayakawa Yoshihisa's commentary suggests that the Supreme Court likely did not intend to create an entirely new or conflicting rule for divorce jurisdiction, but rather to apply the overarching jōri principle to a distinct factual situation not covered by the specific exceptions (like a missing spouse) outlined in the Showa 39 Rule. The core idea was still to ensure access to justice under principles of fairness. However, because the Court did not explicitly detail how the facts differed in a way that connected it to the broader jōri framework beyond the non-recognition issue, some lower courts subsequently tended to treat the Showa 39 Rule and the Heisei 8 Rule as separate, alternative standards, sometimes applying one to divorces between foreign nationals and the other to divorces involving a Japanese national. This, according to Professor Hayakawa, was likely a misinterpretation of the Supreme Court's intent.

Legislative Resolution in the Personal Status Litigation Act

The complexities and potential inconsistencies arising from the case-by-case development of international divorce jurisdiction rules were largely resolved with the codification of these rules in Japan's Personal Status Litigation Act (PSLA), particularly in Articles 3-2 and following (as amended).

The PSLA now contains specific provisions that reflect the principles from both the Showa 39 Rule and this Heisei 8 Rule. For instance, Article 3-2(7) of the PSLA grants jurisdiction to Japanese courts if the plaintiff is domiciled in Japan and, among other "special circumstances," a divorce judgment obtained in the country of the defendant's domicile is not recognized in Japan. This directly addresses the type of "catch-22" situation faced by Mr. X. The PSLA's comprehensive rules aim to provide greater clarity and predictability, without making distinctions based on the nationality pairings of the spouses.

Conclusion

The 1996 Supreme Court "Heisei 8 Rule" decision was a crucial step in the evolution of Japan's approach to international divorce jurisdiction. It specifically addressed the challenging problem faced by individuals caught in a "limping marital status" due to the non-recognition of a foreign divorce decree. By prioritizing the plaintiff's need for access to a competent forum and grounding its decision in the principles of fairness and justice (jōri), the Supreme Court provided a vital remedy. This case, along with earlier precedents, paved the way for the current, more detailed statutory framework governing international personal status litigation in Japan, ensuring that individuals can resolve fundamental aspects of their family lives even amidst complex international legal entanglements.