A Debtor's Inheritance Right: Can Creditors Claim the Reserved Portion?

Decision Date: November 22, 2001

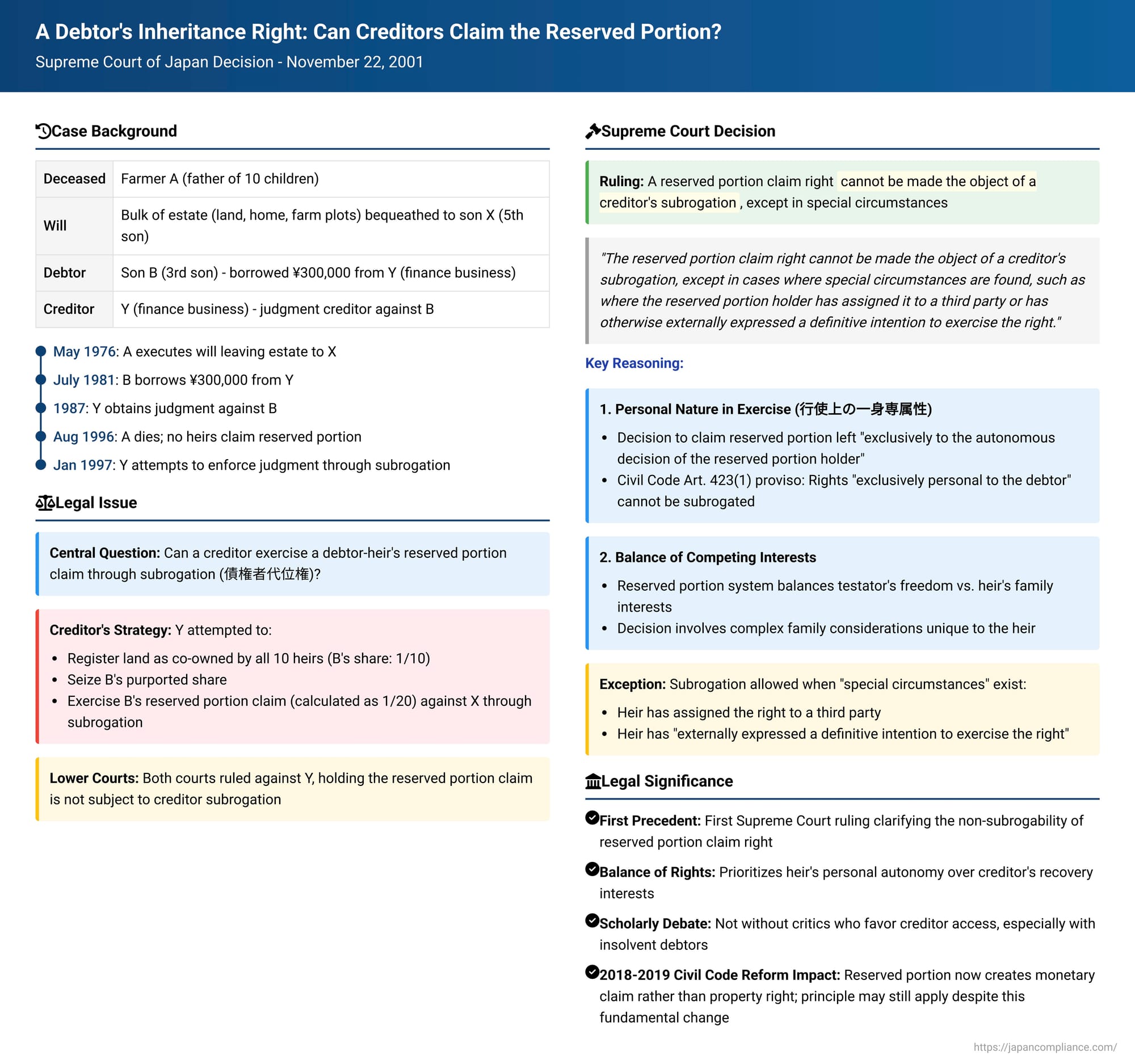

In a significant ruling on November 22, 2001, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan addressed a critical question at the intersection of inheritance law and creditors' rights: Can a creditor step into the shoes of a debtor-heir to exercise the heir's legally reserved portion claim (遺留分減殺請求権, iryūbun gensai seikyūken) against an estate? This case explored the deeply personal nature of the reserved portion claim and set a key precedent under the then-existing Civil Code.

I. The Factual Matrix: A Farmer's Will, a Son's Debt, and a Creditor's Pursuit

The dispute arose from the estate of A, a farmer who passed away in August 1996[cite: 1]. A was a father of ten children, his wife having predeceased him[cite: 1]. One of his sons, X (the fifth son), had dedicated himself to A's agricultural business as a successor and had lived with and supported his parents[cite: 1]. In recognition of this, A had executed a notarized will in May 1976, bequeathing the bulk of his estate—including the main residential land (the "Land in Question"), his home, and numerous agricultural plots—to X[cite: 1]. Two other rice paddies were left to A's fourth son[cite: 1].

One of A's other sons, B (the third son), had financial troubles. B had borrowed ¥300,000 from Y, a finance business, in July 1981[cite: 1]. Y successfully sued B for this debt, obtaining a judgment in 1987[cite: 1]. After A's death, none of A's children, including B, initiated a claim for their reserved portion of the estate[cite: 1]. The reserved portion is a legally protected share of an estate that certain heirs are entitled to, even if a will attempts to disinherit them or leave them a smaller share.

To keep the judgment against B alive, Y filed another lawsuit in 1996 to interrupt the statute of limitations, securing a similar judgment[cite: 1]. In January 1997, Y moved to enforce this judgment. Acting under a creditor's subrogation right (債権者代位権, saikensha daiiken – a right allowing a creditor to exercise a debtor's right in their name to preserve the creditor's claim), Y took steps to have the Land in Question registered as co-owned by all ten of A's children according to their statutory inheritance shares (B's share being 1/10th). Y then initiated compulsory execution proceedings against B's purported 1/10th share, and a seizure order was registered against it.

In response, X, the primary beneficiary under A's will, filed a third-party objection lawsuit in March 1997, seeking to prevent the compulsory execution on the Land in Question. During the proceedings of X's objection suit at the first instance court, Y made another significant move: again claiming to act in subrogation of B, Y formally declared the exercise of B's reserved portion claim against X. Y argued that, by virtue of this subrogated claim, the compulsory execution was valid at least to the extent of B's reserved portion share in the estate, which Y calculated as 1/20th[cite: 1].

II. The Lower Courts' Position: Subrogation Denied

Both the court of first instance and the appellate court sided with X[cite: 1]. They held that the reserved portion claim right is not a right that a creditor can exercise on behalf of their debtor-heir through subrogation[cite: 1]. Consequently, Y's attempt to seize a portion of the Land in Question based on such a subrogated claim was deemed invalid. Y appealed this decision to the Supreme Court[cite: 1].

III. The Supreme Court's Judgment: A Right Too Personal to Subrogate (Generally)

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, affirming the lower courts' decisions. The Court laid down a general principle regarding the subrogation of reserved portion claims:

"The reserved portion claim right cannot be made the object of a creditor's subrogation, except in cases where special circumstances are found, such as where the reserved portion holder (the debtor-heir) has assigned it to a third party or has otherwise externally expressed a definitive intention to exercise the right."

The Court provided detailed reasoning for this conclusion:

A. The Balancing Act of the Reserved Portion System

The judgment began by contextualizing the reserved portion system itself. It serves to balance two competing interests: the testator's freedom to dispose of their property as they wish, and the interests of certain heirs that arise from their family relationship with the deceased.

B. The Heir's Autonomous Decision is Paramount

The Civil Code, in respecting the testator's freedom of disposition, allows a will that infringes upon an heir's reserved portion to initially take effect according to the testator's expressed intentions. The crucial next step—the decision whether to overturn this testamentary disposition and recover the infringed reserved portion—is left "exclusively to the autonomous decision of the reserved portion holder" (referring to the former Civil Code Articles 1031 and 1043).

C. "Personal Nature in its Exercise" (行使上の一身専属性)

Given this emphasis on the heir's personal choice, the Supreme Court concluded that the reserved portion claim right, except in the aforementioned special circumstances, possesses a "personal nature in its exercise" (kōshi-jō no isshin senzoku-sei). This classification is significant because Article 423, paragraph 1, proviso of the Civil Code stipulates that rights "exclusively personal to the debtor" (saumu-sha no isshin ni senzoku suru kenri) cannot be subrogated by a creditor. The Court reasoned that allowing a person other than the reserved portion holder (i.e., a creditor) to intervene in the heir's decision-making process regarding the exercise of this claim would be impermissible.

D. Distinguishing from "Personal Nature in its Attribution" (帰属上の一身専属性)

The Court addressed a potential counter-argument. The former Article 1031 of the Civil Code (related to the reserved portion claim) acknowledged that successors of the reserved portion holder could also exercise this right. This implies that the right is not so personal that it cannot be inherited or otherwise succeeded to. However, the Supreme Court clarified that this merely demonstrates that the right does not have a "personal nature in its attribution" (kizoku-jō no isshin senzoku-sei) – meaning it's not exclusively tied to the original holder for purposes of who can hold the right itself. This, the Court stated, does not negate its personal nature in exercise and therefore does not prevent the application of the rule against subrogation.

E. A Supplemental Rationale: Creditors' Expectations

The Court added a further point to bolster its conclusion: "Moreover, whether a debtor-heir will inherit from an estate in the future is an extremely uncertain matter, contingent upon the existence of estate assets at the time of inheritance commencement and whether the heir chooses to renounce the inheritance. Creditors of an heir should not expect such potential future inheritance to serve as collateral security. Therefore, interpreting the law in this way does not unfairly harm creditors."

Based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court found that Y could not subrogate B's reserved portion claim right in this instance, and thus X's third-party objection to the seizure was valid.

IV. Analysis and Enduring Implications of the Ruling

This 2001 Supreme Court decision was a landmark as the first top-court ruling to directly clarify the non-subrogability (in general) of the reserved portion claim right[cite: 1].

A. The "Personal Nature in Exercise" Doctrine Affirmed

The Court's reliance on the "personal nature in exercise" doctrine aligned with a significant stream of academic thought which posits that rights whose exercise fundamentally depends on the holder's personal discretion should be shielded from creditor subrogation[cite: 1]. The reserved portion claim, involving deep family considerations and respect for the deceased's wishes versus the heir's own financial needs and desires, fits this description well. The decision to claim it can involve weighing complex emotional, familial, and financial factors that are unique to the heir.

B. Scholarly Debate and Alternative Views

It is important to note, however, that this ruling was not without its critics in the academic sphere[cite: 3]. The PDF commentary accompanying this case highlights that many legal scholars argued in favor of allowing creditors to subrogate the reserved portion claim, particularly when the debtor-heir is insolvent[cite: 3]. These scholars often prioritized the creditor's need to recover their legitimate claims over the heir's freedom to choose not to exercise a valuable property right[cite: 3]. The argument was that once an inheritance commences and the heir has a valuable reserved portion claim, it forms part of their assets, and creditors should be able to access it to satisfy their claims, especially if the heir's inaction is seen as detrimental to the creditors.

C. The "Special Circumstances" Exception: A Source of Ambiguity?

While the Court provided an exception for "special circumstances where the reserved portion holder... has externally expressed a definitive intention to exercise the right (e.g., by assigning it to a third party)," this phrase itself has been a subject of discussion. The PDF commentary points out that the precise scope of what constitutes such "special circumstances" or an "externally expressed definitive intention" remained somewhat undefined, potentially leaving room for future litigation on this point[cite: 3]. For example, would merely stating an intention to claim, without taking formal steps, suffice? Or would negotiations for settlement based on the claim meet the criteria? These nuances were not fully fleshed out.

D. The "Collateral Security" Argument and its Reach

The Court's supplemental argument concerning creditors not expecting future inheritance as collateral also introduced an interesting dimension. While intended to reinforce the main conclusion, this line of reasoning, as the PDF commentary notes, could lead to questions in different factual scenarios[cite: 3]. For instance, if an inheritance has already commenced, the heir has not renounced, and the period for renunciation has passed, the heir's rights (including any potential reserved portion claim) are arguably less "uncertain"[cite: 3]. If such an heir then obtains financing, perhaps implicitly using their potential claim as a form of assurance, the "uncertainty" argument might carry less weight[cite: 3]. The question then becomes whether such a situation could fall under the "special circumstances" exception[cite: 3]. The emphasis placed on this "collateral security" viewpoint could influence how such borderline cases are interpreted[cite: 3].

E. Scope: Applicable to Other Creditors?

The general phrasing of the judgment suggests that its reasoning might extend beyond the specific facts of an heir's creditor attempting subrogation[cite: 4]. The PDF commentary suggests it might also apply to scenarios involving creditors of the deceased attempting a similar subrogation, though this involves different considerations[cite: 4].

F. Impact of the 2018 Civil Code Reforms on Inheritance Law

This Supreme Court decision was rendered under the Civil Code provisions existing before the major reforms to inheritance law in 2018 (effective 2019). Under the pre-2018 law, the reserved portion claim right (旧民法1031条) was a "formative right" (形成権, keiseiken), meaning its exercise directly altered property rights, potentially causing a portion of an inherited asset to revert to the claimant[cite: 1].

The 2018 reforms fundamentally changed the nature of the reserved portion remedy[cite: 1]. Now, exercising a reserved portion right (new Civil Code Art. 1046) results in a monetary claim (金銭債権, kinsen saiken) against the recipient of the infringing gift or bequest for an amount equivalent to the value of the infringed reserved portion[cite: 1]. The claimant no longer automatically gets a share in the specific property itself.

Despite this significant change from a property-based claim to a purely monetary one, the core reasoning of the 2001 Supreme Court decision may still hold relevance[cite: 4]. The Court's emphasis on the heir's "autonomous decision" whether to recover the infringed portion, based on the balance between the testator's freedom of disposition and the heir's personal interests, is a principle that arguably transcends the specific legal form of the claim[cite: 4]. As the PDF commentary suggests, this underlying rationale could support the continued non-subrogability (in general) of the new monetary reserved portion claim[cite: 4].

However, the transformation into a monetary claim might also fuel arguments for easier creditor access, as monetary claims are generally seen as less "personal" than rights to alter property dispositions based on family ties. The PDF commentary rightly notes that the applicability of this 2001 precedent to the new system will require careful observation of future court decisions and ongoing scholarly discussion, especially given the pre-existing criticisms of the ruling[cite: 4].

V. Conclusion: Protecting the Heir's Personal Choice

The November 22, 2001, Supreme Court judgment carved out a significant position on the creditor's ability to access a debtor-heir's reserved portion claim. By emphasizing the highly personal nature of the decision to exercise this right, rooted in the unique dynamics of family relationships and testamentary wishes, the Court shielded it from subrogation by creditors in most circumstances under the old Civil Code. While an exception for "special circumstances" was acknowledged, the general rule prioritized the heir's autonomy. The evolution of inheritance law, particularly the shift to a monetary claim for reserved portions, means that the final word on creditor subrogation under the new system is yet to be definitively written, but this landmark decision will undoubtedly remain a crucial reference point in the ongoing discourse.