A Crime of Life or Property? A 1929 Japanese Ruling on the Essence of Robbery-Murder

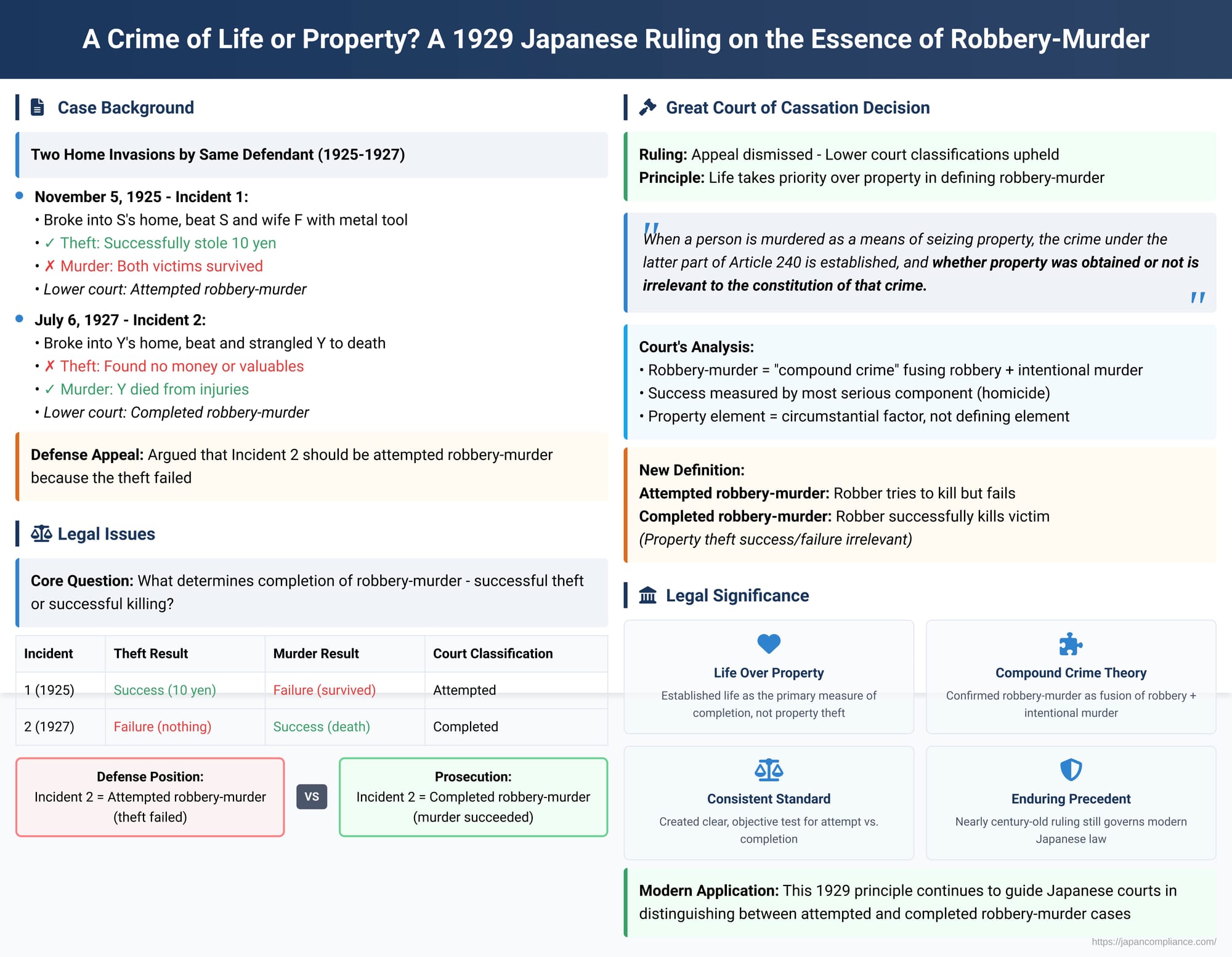

When a robber kills their victim, what defines the completion of the crime? Is it the successful theft of property, or is it the tragic loss of life? Consider two scenarios: In the first, a robber attacks a homeowner, steals their money, but fails to kill them. In the second, a robber kills the homeowner but is unable to find any valuables to steal. Which of these constitutes a "completed" robbery-murder, and which is an "attempt"?

This profound question, which probes the very nature of one of the gravest offenses, was definitively answered by Japan's Great Court of Cassation (the predecessor to the modern Supreme Court) in a foundational ruling on May 16, 1929. The decision, involving a defendant who committed two brutal home invasions with different outcomes, established a clear and enduring principle: in the crime of robbery-murder, the benchmark for success is the taking of a life, not the taking of property.

The Facts: Two Brutal Home Invasions

The defendant in the case went on a crime spree, committing two separate but chillingly similar home invasions.

- Incident 1 (Theft Success, Murder Failure): On November 5, 1925, the defendant broke into the home of a man named S to commit theft. While searching for valuables near the sleeping couple, he thought the wife, F, had awoken. Fearing discovery, he decided to kill them and take their property by force. He viciously beat both S and F on the head with a metal tool (shikarappu) until they fell unconscious. Believing them to be dead, he then stole 10 yen. However, both victims survived their injuries. The lower court classified this as attempted robbery-murder.

- Incident 2 (Theft Failure, Murder Success): On July 6, 1927, the defendant broke into the home of another man, Y, again with the intent to steal. When he thought Y had noticed him, he again resolved to kill him and take his property. He beat Y with a piece of wood and then strangled him to death with a piece of cloth. After the murder, he searched the room but was unable to find any money or valuables to steal. The lower court classified this as completed robbery-murder.

The lower court treated both incidents as a single, continuous offense and sentenced the defendant to death. The defendant's lawyer appealed, focusing on a specific point of law regarding the second incident. He argued that because the theft had failed, the crime could only be an attempted robbery-murder, and the court had erred by convicting his client of the completed crime.

The Legal Framework: The Nature of Robbery-Murder in Japan

The defense's argument centered on the interpretation of Article 240 of the Penal Code, which governs robbery resulting in injury or death. A central theoretical debate in Japanese law is whether this statute is intended to cover only cases where a robber unintentionally causes death (a "result-qualified crime") or whether it also encompasses cases where the robber intentionally kills the victim (making it a "compound crime" or ketsugō-han that fuses robbery and murder).

After some fluctuation in the early 20th century, the Japanese judiciary, including in this 1929 decision, settled on the latter interpretation. The prevailing view, both in case law and among legal scholars, is that Article 240 is a "compound crime" statute that covers both intentional and unintentional killings during a robbery. The primary reasons for this interpretation are the statute's extremely severe penalty ("death or life imprisonment," which seems to anticipate intentional killing), its specific wording, and the existence of a provision for "attempt" (Article 243), which logically only applies to intentional crimes.

The Court's Landmark Ruling: Life is the Deciding Factor

The Great Court of Cassation rejected the defense's appeal and affirmed the lower court's judgment. In doing so, it laid down the definitive rule for what constitutes an "attempt" in the context of robbery-murder.

The Court's core principle was clear and direct:

"When a person is murdered as a means of seizing property, the crime under the latter part of Article 240 is established, and whether property was obtained or not is irrelevant to the constitution of that crime."

The Court reasoned that the law's purpose was to create a specific and severe punishment for the ultimate outcome of a robbery turning fatal. From this, it logically followed that the success or failure of the crime should be measured by its most serious component—the harm to human life.

Therefore, the Court defined attempted robbery-murder as the scenario where:

"...a robber, with intent, tries to cause the death of a person but does not succeed."

The success or failure of the property theft is, in the Court's words, "not a constituent element" of the crime of robbery-murder.

Applying this principle, the lower court's classifications were correct. In the first incident, the defendant tried to kill the victims but failed; therefore, it was an attempted robbery-murder, even though he successfully stole the 10 yen. In the second incident, he successfully killed the victim; therefore, it was a completed robbery-murder, even though he failed to steal anything.

Analysis: Why is the Theft Element Secondary?

The Court's decision to prioritize the outcome of the violence over the outcome of the property crime is rooted in a clear and consistent legal logic.

First, as noted, the extreme gravity of the statutory penalty indicates that the legislature viewed the loss of life as the defining feature of the offense. The crime is not merely an aggravated property crime; it is a crime against life committed in the context of a robbery.

Second, because robbery-murder is understood as a "compound crime" that fuses the elements of robbery and intentional murder, the completion of the most serious component (the homicide) renders the entire compound offense complete. The property element is seen as a circumstantial or motivating factor rather than the ultimate result that defines completion.

Finally, the very concept of a criminal "attempt" applies only to intentional acts. One cannot "attempt" to cause an unintentional result. Since the intentional aspect of robbery-murder is the act of killing, it is logical that the "attempt" should be measured by the success or failure of that intentional act.

Conclusion: Prioritizing Life Over Property

The 1929 decision of the Great Court of Cassation, consistently upheld by the post-war Supreme Court, provides a clear and enduring framework for one of the most serious crimes in the penal code. It definitively established that in the crime of robbery-murder, the success or failure of the act is measured by the harm inflicted upon the victim's life, not their property.

The ruling's legacy is a legal standard that is both logical and reflects a profound moral and legal judgment:

- Completed Robbery-Murder: Occurs when the victim is killed during a robbery, regardless of whether any property is successfully stolen.

- Attempted Robbery-Murder: Occurs when the robber tries to kill the victim but fails, regardless of whether any property is successfully stolen.

This nearly century-old precedent ensures that the law places the highest possible value on the protection of human life, treating the property crime that sets the stage for the violence as a critical but ultimately secondary element.