A Crime Against the Nation or its Wallet? A Japanese Ruling on Fraud and Public Policy

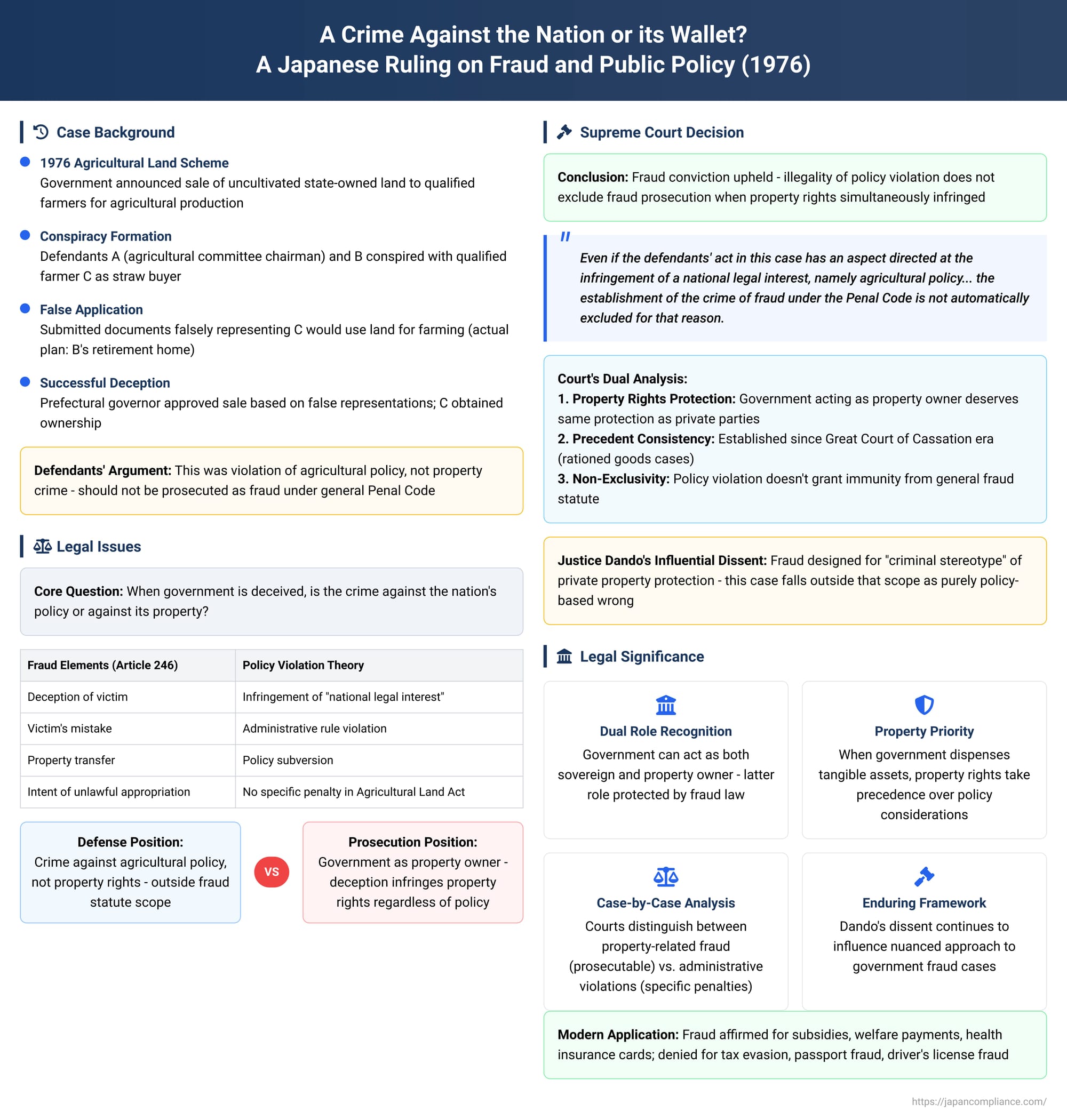

Imagine a person lies on a government application to receive a benefit they are not entitled to—for example, agricultural land intended only for active farmers, or a subsidy earmarked for a specific industry. Is this act simply a violation of administrative rules, to be handled by the relevant government agency? Or is it the full-blown property crime of fraud, punishable under the general Penal Code? This question, which pits the government's role as a policymaker against its role as a property owner, was the subject of a landmark and highly influential decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on April 1, 1976.

The case, involving a scheme to acquire state-owned farmland for non-farming purposes, is famous not only for its majority decision but also for a powerful dissenting opinion by Justice Dando Shigemitsu, which framed a fundamental debate that continues to resonate in Japanese law: when a person deceives the state, is their crime against the nation's policy or against its wallet?

The Facts: The Retirement Home on the Farmland

The case began when the Japanese government, in accordance with the Agricultural Land Act, announced its intention to sell off parcels of uncultivated state-owned land. The express policy goal was to transfer this land to qualified individuals who would cultivate it and contribute to the nation's agricultural production.

The defendants, A (the chairman of the local agricultural committee responsible for the process) and B, conspired with a third person, C. C was a person who met the government's official criteria and was qualified to purchase the land. However, the conspirators' true plan was for C to act as a straw buyer. They intended for C to acquire the land from the government and then immediately transfer it to defendant B, who wanted the land not for farming, but as a site for his retirement home.

To execute their plan, they submitted the required application documents, including a purchase offer, to the prefectural governor, who was in charge of the sale. In these documents, they concealed their true intentions and falsely represented that C, a qualified farmer, would be using the land for agricultural purposes. Deceived by this application, the governor approved the sale, and C obtained ownership of the state-owned land. The lower High Court found the defendants guilty of fraud, and they appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Crossroads: A National Interest vs. a Property Right

The core legal issue was whether this deception constituted the crime of fraud under Article 246 of the Penal Code. The defense's argument, echoed in Justice Dando's dissent, was that their actions were not a typical property crime. The "victim" was not an individual being cheated out of their savings, but the state's agricultural policy. They argued that their act was an infringement of a "national legal interest," not a private property right, and therefore should not be prosecuted as fraud unless the Agricultural Land Act itself contained a specific penalty for such deception (which it did not).

This raised a fundamental question: When the government is deceived, should the law focus on the subversion of its public policy or the loss of its property?

The Majority Opinion: Fraud is Fraud, Even Against the State

The majority of the Supreme Court rejected the defendants' arguments and upheld the fraud conviction. The Court established a clear and pragmatic principle that remains the law in Japan.

The Court's reasoning was that the two types of harm are not mutually exclusive. It stated:

"Even if the defendants' act in this case has an aspect directed at the infringement of a national legal interest, namely agricultural policy... the establishment of the crime of fraud under the Penal Code is not automatically excluded for that reason."

The key principle, the Court explained, is that as long as the deceptive act simultaneously infringes on property rights—which are the protected interest of the crime of fraud—a fraud conviction is appropriate. The government, when it owns and sells land, is acting as a property owner. Deceiving it to acquire that property is an infringement of its property rights. The Court noted that this has been the established precedent since the era of its predecessor, the Great Court of Cassation, in cases involving the fraudulent acquisition of rationed goods. The fact that the deception also subverts a national policy does not provide immunity from the general fraud statute.

The Dissenting Opinion: A Crime Outside the "Stereotype" of Fraud

Justice Dando's dissenting opinion offered a powerful theoretical counter-argument. He argued that the general crime of fraud was designed to protect private, individual property interests and that the defendants' actions fell outside this "criminal stereotype."

His reasoning was that the only reason the defendants' act was wrongful was because of the existence of the Agricultural Land Act and its specific policy goals. He wrote, "if this kind of provision in the Agricultural Land Act did not exist, a sale like the one in this case would not be a problem at all from the beginning." Since the illegality stemmed entirely from the contravention of a specific national policy, the crime was an offense against that policy, not an offense against property in the traditional sense.

He concluded that if the legislature had deemed such an act worthy of punishment, it should have included a specific penalty provision within the Agricultural Land Act itself. The legislature's silence, in his view, meant the act was not a crime. He distinguished this from other administrative laws, like the post-war food rationing ordinance, which explicitly stated that in cases of fraud, the Penal Code's provisions should apply.

Analysis: Drawing the Line in Practice

The majority opinion remains the controlling law, but Justice Dando's dissent highlighted an enduring tension that the Japanese courts have continued to navigate on a case-by-case basis. The key has been to determine when the government is acting primarily as a property owner versus when it is acting in a purely sovereign or administrative capacity. A review of Japanese case law reveals a pattern:

- Where Fraud is Affirmed: The courts consistently affirm fraud convictions when the government is dispensing tangible financial assets or valuable benefits. This includes the fraudulent acquisition of subsidies, welfare payments, and government-issued documents that have direct economic value, such as health insurance cards (which grant the right to receive medical services at a reduced cost). In these instances, the government's role is akin to that of a private entity managing and distributing assets, and its property rights are protected by the general fraud statute.

- Where Fraud is Denied: Conversely, the courts have refused to apply the fraud statute to acts aimed at subverting purely sovereign or administrative functions. This includes tax evasion, evading fines or public fees, and fraudulently obtaining documents that merely certify a status or qualification without conferring a direct economic benefit, such as a passport or a driver's license. In these cases, the harm is seen as an offense against the tax or administrative system itself, and is punishable only under the specific penalty provisions of the relevant administrative laws.

Conclusion: The Enduring Tension

The 1976 Supreme Court decision established that defrauding the government can indeed be prosecuted as a general property crime, even when the deception also serves to subvert a public policy. The majority's pragmatic view—that an infringement on the state's property is still an infringement on property—remains the law of the land.

However, Justice Dando's influential dissent serves as a constant reminder of the theoretical complexities involved. His argument has encouraged a nuanced, case-by-case approach from the courts, which carefully examine the nature of the government function at issue. The enduring legacy of the decision is the ongoing, careful balancing act the law performs: when the government acts like a property owner, its wallet is protected by fraud law; when it acts as a sovereign, its policies are protected by administrative law. This landmark case and its powerful dissent continue to define the complex boundary between public policy and property crime in Japan.