A Creditor's Ultimate Tool? Forcing a Partner's Withdrawal in Japanese Partnerships – A Supreme Court Deep Dive

Judgment Date: December 20, 1974

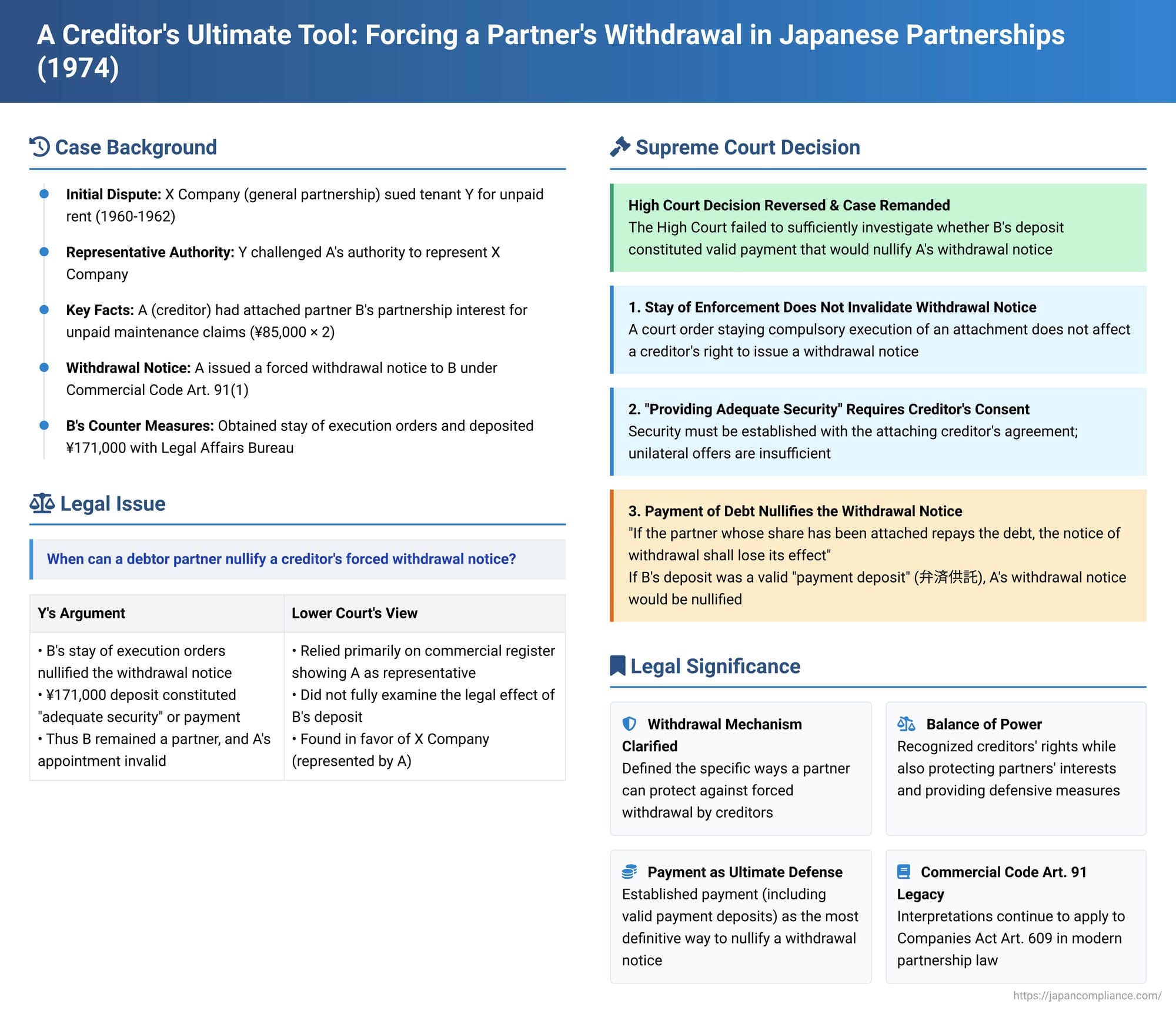

In the realm of Japanese partnership law, specifically concerning general partnerships (Gomei Gaisha), creditors possess a unique and potent remedy when seeking to recover debts from a partner: the ability to attach the partner's partnership interest and then, under specific conditions, force that partner's withdrawal from the company. This mechanism, currently enshrined in Article 609 of the Companies Act (formerly Article 91 of the Commercial Code), allows creditors to access the value of the partner's interest, which might otherwise be difficult to liquidate due to transfer restrictions.

A pivotal Supreme Court decision dated December 20, 1974, meticulously examined the conditions under which such a creditor-initiated notice of withdrawal can be nullified by the debtor partner. The case, originally a seemingly straightforward dispute over unpaid rent, escalated into a fundamental inquiry into corporate representation and the intricacies of this forced withdrawal system.

The Underlying Dispute: A Rent Claim Exposes Deeper Issues

The initial lawsuit involved X Company, a general partnership engaged in real estate leasing, suing its tenant, Y, for unpaid rent. Y had initially leased property from X Company, with the rent gradually increasing over time. When Y allegedly failed to pay rent for a period spanning from April 1960 to December 1962, X Company initiated legal action to recover the arrears and associated damages.

Y's defense was multifaceted, including claims of an internal dispute within X Company regarding the property's ownership and an alleged agreement with B, the brother of A (X Company's representative partner), to pay rent to B instead. The first instance court sided with X Company.

The Core Issue: The Representative's Authority and a Partner's Disputed Withdrawal

In the appellate proceedings, the case took a critical turn. Y challenged the very authority of A to represent X Company in the lawsuit. This challenge formed the crux of the matter that eventually reached the Supreme Court.

The facts pertinent to A's representative authority were as follows:

- A was recorded in X Company's commercial register as having assumed the position of representative partner on February 22, 1960, with the registration effected on March 7, 1960.

- Y contested the validity of A's appointment. The argument centered on A's actions towards another partner in X Company, B. A was a creditor of B, holding claims for maintenance payments established by court orders (two claims of ¥85,000 each).

- To satisfy these claims, A had, on two occasions (November 19, 1958, and March 20, 1959), attached B's partnership interest in X Company.

- Following these attachments, A issued a notice of withdrawal to B, invoking the provisions of then-Commercial Code Article 91, Paragraph 1. This provision allowed a creditor who had attached a partner's interest to force the partner's withdrawal at the end of the business year by giving at least six months' prior notice to both the company and the debtor partner.

- A contended that B was consequently forced to withdraw from X Company at the end of the relevant business year, which was December 31, 1959. With B purportedly no longer a partner, A claimed to have validly become the representative partner.

Y, the tenant, countered A's assertions by highlighting B's efforts to prevent the forced withdrawal:

- B had obtained court orders for a stay of compulsory execution concerning A's attachments on two occasions (December 12, 1958, and August 10, 1959).

- Furthermore, on December 28, 1959, just days before the purported withdrawal date, B deposited ¥171,000 (the total amount of A's claims) with the Nagoya Legal Affairs Bureau. Y argued this deposit was made as "adequate security" under then-Commercial Code Article 91, Paragraph 2, which stipulated that a withdrawal notice would lose its effect if the debtor partner paid the debt or provided adequate security.

Based on these actions, Y argued that A's withdrawal notice against B had been nullified, meaning B remained a partner in X Company. If B was still a partner, A's subsequent appointment as representative partner, allegedly without B's consent, would be invalid. Thus, A would lack the legal standing to represent X Company in the rent collection lawsuit against Y.

The High Court, however, dismissed Y's arguments regarding A's lack of authority, relying primarily on the entries in X Company's commercial register, and found in favor of X Company, even increasing the amount of unpaid rent awarded. Y then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Clarifications on Nullifying a Forced Withdrawal Notice

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of December 20, 1974, reversed the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further examination. The Court made three crucial pronouncements on the conditions that affect the validity of a creditor's forced withdrawal notice under the then-Commercial Code Article 91 (now Companies Act Article 609):

1. Stay of Enforcement Does Not Invalidate the Withdrawal Notice

The Supreme Court first addressed Y's argument that B's obtaining court orders to stay the compulsory execution of A's attachments on B's partnership interest nullified the withdrawal notice.

The Court held that the effect of a creditor's withdrawal notice, issued after attaching a partner's interest, is not affected by a court order staying the compulsory execution of that attachment.

This distinction is critical: a stay of execution merely suspends the procedural progression of the enforcement by an execution agency. It does not extinguish or alter the underlying substantive rights of the creditor, one of which, under this specific statutory scheme, is the right to initiate the forced withdrawal process. The right to issue the withdrawal notice is a distinct legal power granted to the attaching creditor, separate from the mechanics of the attachment's execution itself.

2. "Providing Adequate Security" Requires the Creditor's Consent

Next, the Court examined the provision allowing a withdrawal notice to be nullified if the debtor partner "provided adequate security" (Article 91, Paragraph 2). Y contended that B's deposit of ¥171,000 with the Legal Affairs Bureau constituted such security.

The Supreme Court clarified that "providing adequate security" sufficient to nullify a withdrawal notice means the debtor partner has established a security interest (e.g., a pledge or mortgage) or concluded a guarantee contract with the attaching creditor. A mere unilateral offer to provide security, or the act of setting up a security interest or guarantee contract without the attaching creditor's consent or agreement, does not qualify as "providing adequate security" under this provision.

This interpretation suggests that the "provision of security" is a bilateral act requiring the creditor's acceptance. Legal scholars have noted a parallel here with the civil law concept of extinguishing a right of retention by offering alternative security, which generally requires the lienholder's consent. If the creditor unreasonably refuses an objectively adequate offer of security, the debtor partner might, in theory, need to seek a court judgment compelling the creditor's acceptance or a declaration that the offered security is adequate, though the Supreme Court did not delve into this specific scenario.

3. Payment of the Debt Nullifies the Notice – The Linchpin for Remand

The third, and most critical point for the outcome of the appeal, concerned the effect of payment. Article 91, Paragraph 2 explicitly stated that if the partner whose interest was attached pays the debt, the withdrawal notice loses its effect.

The Supreme Court emphasized this, stating: "It is clearly stipulated by the same article that if the partner whose share has been attached repays the debt, the notice of withdrawal shall lose its effect."

This led to the core reason for the remand. Y had argued that B's deposit of ¥171,000 on December 28, 1959, was intended to settle the debt owed to A. The Supreme Court reasoned that if this deposit by B for the debt related to the attachment had the effect of a valid "payment deposit" (bensai kyotaku), then the withdrawal notice issued by A would indeed lose its effect. A payment deposit is a legally recognized method for a debtor to discharge a debt when, for example, the creditor refuses to accept payment or their whereabouts are unknown.

If the notice was nullified, B would have remained a partner, and A's subsequent claim to be the representative partner of X Company could be negated.

The High Court had failed to sufficiently investigate whether B's deposit constituted a valid payment deposit that effectively discharged the debt to A. It had, in the Supreme Court's view, too readily accepted A's representative authority based solely on the commercial register, despite the dispute. This failure to fully examine the pertinent facts and legal implications of the deposit constituted a "failure of full deliberation" (shinri fujin), which clearly affected the judgment's outcome.

Therefore, the Supreme Court reversed the High Court's decision and remanded the case, instructing the lower court to thoroughly examine, among other things, whether B's deposit was a legally effective payment of the debt to A.

The Forced Withdrawal System (Companies Act Article 609): Purpose and Implications

The Supreme Court's decision sheds light on the workings of a unique feature of Japanese partnership law – the creditor's right to force a partner's withdrawal (now Companies Act Article 609).

- Rationale for the System: This extraordinary remedy was introduced into law (originally in a 1938 Commercial Code amendment) to address a practical problem for creditors. Partnership interests in general partnerships (Gomei Gaisha) or limited partnerships (Goshi Gaisha) can be difficult to liquidate. Transferring such an interest often requires the consent of all other partners (e.g., Companies Act Article 585). This makes it hard for a creditor who has attached a partner's interest to realize its value through a sale. The forced withdrawal mechanism provides a more direct route: the creditor can compel the partner's exit, and the attachment then applies to the partner's right to a monetary payout of their share of the company's net assets upon withdrawal (Companies Act Article 611). The partner can demand this payout in cash, regardless of the nature of their original contribution.

- Mechanism of Forced Withdrawal:

- The creditor must first validly attach the debtor partner's partnership interest.

- The creditor must then give at least six months' notice before the end of the company's business year, both to the company and to the debtor partner.

- If the notice is not nullified, the debtor partner automatically withdraws from the partnership at the precise moment the business year concludes.

- The creditor's attachment lien extends to the partner's claim for the withdrawal payout. The creditor can then collect this claim or obtain a transfer order for it.

- Balancing Creditor Rights and Partner Protection: While providing a strong tool for creditors, the law (Article 609, Paragraph 2) also offers the debtor partner two primary ways to nullify the withdrawal notice and retain their partnership status:

- Payment of the Debt: As affirmed by the Supreme Court, full payment of the underlying debt to the attaching creditor extinguishes the basis for the forced withdrawal. This includes valid payment deposits if the creditor refuses acceptance.

- Provision of Adequate Security: If the debtor partner provides security that is agreed upon by the attaching creditor, the notice is also nullified. The Supreme Court's decision underscores the consensual nature of this option.

- Nature of the Withdrawal Right: The creditor's right to initiate withdrawal is generally understood as a "right of formation" (keiseiken), meaning it can be exercised by a unilateral declaration (the notice) to the relevant parties (the company and the debtor partner) without needing their active cooperation, provided the statutory conditions are met.

- Mandatory Provision: The provisions of Article 609 are considered mandatory law (kyokohoki). This means that a partnership cannot, through its articles of association or by agreement, exclude or limit this statutory right of a partner's creditors.

- Potential for Abuse and Bad Faith: The commentary accompanying the case notes that if an attaching creditor refuses an objectively adequate offer of security, not because the security is insufficient but because their primary motive is to oust the partner from the company rather than to secure their debt, such conduct could potentially be challenged as an abuse of rights. However, the Supreme Court's 1974 decision focuses on the necessity of creditor consent for the security to be effective under the statute as written.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1974 ruling provides critical clarifications regarding the powerful, yet nuanced, mechanism of creditor-forced partner withdrawal. It confirms that while a stay of execution on the attachment itself won't stop the withdrawal notice, and providing "adequate security" requires the creditor's agreement, the most definitive way for a debtor partner to nullify such a notice is by satisfying the underlying debt. The Court's emphasis on the potential validity of a "payment deposit" as fulfilling this requirement underscores the importance of a thorough factual examination by lower courts. This decision continues to inform the understanding of creditor-partner dynamics within Japanese general partnerships, highlighting the balance the law attempts to strike between effective creditor remedies and the protection of a partner's ongoing interest in their company.