A Constitutional Backstop: Japan's Supreme Court on Direct Compensation Claims for "Special Sacrifices"

Date of Judgment: November 27, 1968

Case: Case Concerning Violation of the Rivers Vicinity Land Restriction Ordinance

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Grand Bench

Introduction: When Regulation Inflicts Extraordinary Loss

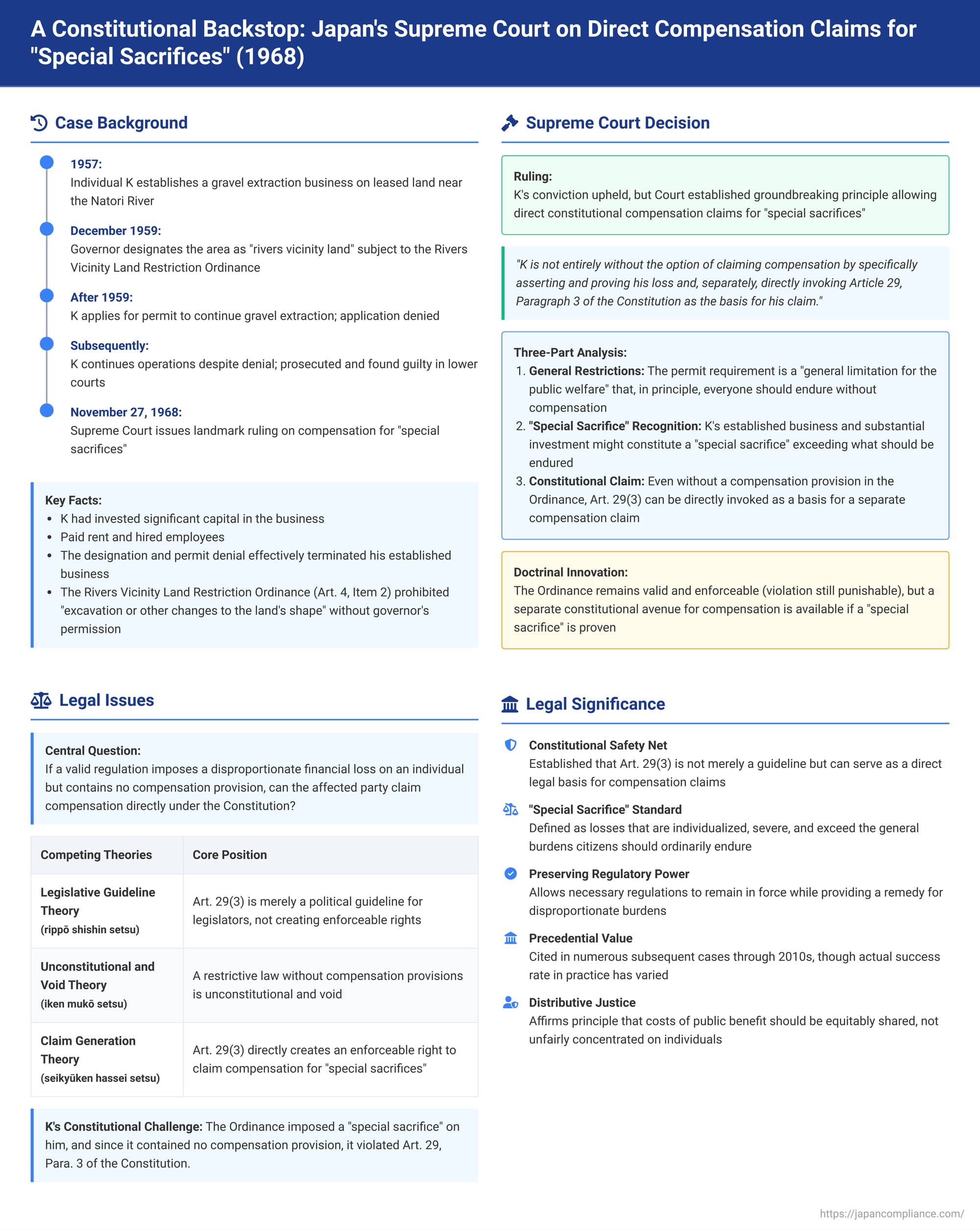

Governments routinely enact regulations for the public welfare—to manage resources, ensure safety, or protect the environment. Generally, citizens are expected to bear the incidental burdens these regulations may impose as part of their social obligations. But what happens when a perfectly lawful regulation, intended for the common good, inflicts a disproportionately severe financial loss on a specific individual or business, and the regulation itself offers no mechanism for compensation? Is the affected party left without a remedy? This critical question was at the heart of a landmark decision by the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan on November 27, 1968, a case that explored the possibility of directly invoking Article 29, Paragraph 3 of the Constitution (guaranteeing "just compensation" for private property taken for public use) to claim redress.

The Gravel Extractor's Predicament: K's Story

The case involved an individual, K, who, since 1957, had been operating a gravel extraction business. He leased privately-owned land situated outside the man-made embankments of the Natori River in Miyagi Prefecture and had invested considerable capital into his enterprise.

In December 1959, the Governor of Miyagi Prefecture designated this entire area, including the riverbed, as "rivers vicinity land" (kasen fukinchi). This designation brought K's activities under the purview of the Rivers Vicinity Land Restriction Ordinance (Kasen Fukinchi Seigenrei). Article 4, Item 2 of this Ordinance prohibited actions such as "excavation or other changes to the land's shape" within these designated areas without obtaining prior permission from the governor.

K duly applied for a permit to continue his gravel extraction, but his application was denied. Believing his livelihood was at stake, K continued his operations despite the denial. Consequently, he was prosecuted for violating Article 4, Item 2 of the Ordinance, under its penal provision, Article 10. He was found guilty in both the first instance court and on initial appeal.

K's Defense: An Unconstitutional "Special Sacrifice"

In his final appeal to the Supreme Court, K did not merely contest the facts or the interpretation of the Ordinance. He mounted a profound constitutional challenge. He argued that when a regulation like Article 4, Item 2 of the Ordinance is applied to land where individuals are already lawfully conducting business operations (as he was), it imposes a "special sacrifice" (tokubetsu no gisei) on those specific persons. Such a sacrifice, he contended, constitutionally necessitates compensation.

Since the Rivers Vicinity Land Restriction Ordinance, particularly the restrictive Article 4, Item 2, and its associated penal Article 10, contained no provision for compensating such losses, K argued that these provisions were in direct violation of Article 29, Paragraph 3 of the Constitution. He asserted that the relevant parts of the Ordinance were therefore unconstitutional and void, and as such, he should be acquitted of the criminal charges.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: A Nuanced Approach

The Supreme Court's Grand Bench ultimately dismissed K's appeal, meaning his conviction was upheld. However, the reasoning behind this decision was far from a simple affirmation of the lower courts' findings. It offered a nuanced interpretation of constitutional property rights and compensation, opening a new avenue for potential redress in similar situations. The Court's judgment can be understood in three key parts:

Part 1: General Restrictions are Permissible and Ordinarily Uncompensated

The Court first addressed the general nature of the restriction imposed by Article 4, Item 2 of the Ordinance. It stated that this provision, requiring a governor's permit for activities like excavation in designated river vicinity areas, is fundamentally aimed at preventing situations detrimental to river management. Such restrictions, the Court reasoned, are:

"a general limitation for the public welfare, which, in principle, everyone should endure."

As a general rule, such limitations do not inherently impose a "special sacrifice" on specific individuals. Therefore, the Court concluded that making compensation a prerequisite for imposing this type of general restriction is not constitutionally required. Consequently, the mere absence of a compensation provision in Article 4, Item 2 did not render that article (or its penal counterpart, Article 10) unconstitutional and void.

Part 2: Acknowledging the Possibility of "Special Sacrifice" in Specific Circumstances

Despite upholding the general validity of the Ordinance's restrictive clause, the Court then turned to K's particular circumstances. It acknowledged the evidence showing that K had:

- Paid rent for the land.

- Hired employees.

- Made substantial capital investments.

- Operated an established gravel extraction business.

The designation of the area as "rivers vicinity land" and the subsequent denial of his permit meant that K could no longer continue his established business, leading to potentially significant financial losses. The Supreme Court stated:

"If that is so, then his financial sacrifice, although resulting from a necessary restriction for public purposes, might exceed the scope of limitations that should generally be endured as a matter of course, and there is room to consider it a 'special sacrifice.'"

The Court found that the lower appellate court's suggestion that K would not be entitled to compensation even if he had suffered such a loss was "not appropriate." It pointed to the spirit of Article 29, Paragraph 3 of the Constitution and noted that other articles within the same Rivers Vicinity Land Restriction Ordinance (Articles 1-3 and 5) did, in fact, provide for compensation (under Article 7) for different types of restrictions. This internal statutory balance further suggested that K's loss might warrant compensation.

Part 3: The Groundbreaking Point – The Possibility of a Direct Constitutional Claim for Compensation

This was the most significant part of the judgment. The Supreme Court reasoned that even though Article 4, Item 2 of the Ordinance did not itself contain a compensation clause for situations like K's, this did not mean that the Ordinance intended to "deny all compensation in every case." Crucially, the Court declared:

"K is not entirely without the option of claiming compensation by specifically asserting and proving his loss and, separately, directly invoking Article 29, Paragraph 3 of the Constitution as the basis for his claim."

Because this avenue for seeking compensation directly under the Constitution might exist for K (in a separate civil proceeding), the Court held that the restrictive Article 4, Item 2, and the penal Article 10 of the Ordinance should not be "immediately deemed unconstitutional and void" for general application. Since the Ordinance itself was not void, K's act of extracting gravel without a permit remained a punishable offense. His conviction was therefore upheld, but the Court had explicitly opened a door for him to potentially seek compensation elsewhere.

The Doctrine of Direct Constitutional Compensation Claims

The 1968 Supreme Court ruling is a landmark because it was the first clear affirmation by Japan's highest court that Article 29, Paragraph 3 of the Constitution could serve as a direct legal basis for an individual to claim compensation for losses caused by state action, even when the specific law or regulation imposing the restriction lacks its own compensation provision.

This doctrine hinges on the concept of a "special sacrifice" (tokubetsu no gisei). Not every financial detriment caused by a public welfare regulation qualifies. A "special sacrifice" implies a loss that is:

- Individualized and particularly severe.

- Goes beyond the general, diffuse burdens that all citizens are expected to bear as part of living in an organized society.

- Imposed for the public good, but unfairly concentrates the cost of that public good on one or a few individuals.

This "special sacrifice" standard distinguishes such cases from those where restrictions are considered part of the inherent limitations on property rights for public safety (as seen, for example, in the 1963 Nara Reservoir Ordinance case, where prohibitions on dangerous uses of reservoir embankments were deemed uncompensable because they fell within the owner's "duty to endure").

Theories on the Effect of Lacking Compensation Provisions

Before this 1968 decision, there was significant academic and judicial debate in Japan about the legal effect when a law imposed a restriction that seemed to warrant compensation but provided no mechanism for it. Three main theories existed:

- Legislative Guideline Theory (rippō shishin setsu): This minority view held that Article 29(3) was merely a political or moral guideline for the legislature, urging it to provide compensation, but did not create a legally enforceable right for individuals if the legislature failed to do so.

- Unconstitutional and Void Theory (iken mukō setsu): This theory argued that if a law imposed a restriction requiring compensation but failed to include a compensation provision, the restrictive law itself was unconstitutional and therefore void. Compensation was seen as a necessary condition for the validity of the restriction.

- Claim Generation Theory (seikyūken hassei setsu): This theory proposed that Article 29(3) directly creates an enforceable right to claim compensation from the state if a "special sacrifice" occurs due to a public taking or restriction, even if the specific law is silent on compensation. The restrictive law itself would generally remain valid and effective, but the affected individual could sue for compensation directly under the Constitution.

The 1968 Supreme Court ruling decisively endorsed the Claim Generation Theory. This approach allows necessary public welfare regulations to remain in force, avoiding a "regulatory vacuum" that might occur if such laws were struck down entirely. At the same time, it provides a constitutional safety net for individuals who are made to bear an unfair and disproportionate burden for the public good. It should be noted that even under the Claim Generation Theory, if a law explicitly prohibits compensation in a situation where it is constitutionally due (i.e., for a special sacrifice that is not merely an inherent limitation of property rights), that specific prohibition, or potentially the entire law, might still be deemed unconstitutional.

The Legacy and Limits of the 1968 Ruling

The 1968 decision has been highly influential. It provided a theoretical basis for challenging uncompensated losses arising from various regulatory actions. Subsequent Supreme Court cases have referenced the possibility of direct constitutional claims, for example, in the context of denying the unconstitutionality of certain restrictive administrative actions simply because they lacked bespoke compensation clauses.

However, the practical application and success rate of direct constitutional claims for compensation have been subjects of ongoing discussion. In some instances, while acknowledging the possibility of such claims, the Supreme Court has found alternative statutory grounds for compensation or has determined that a "special sacrifice" was not present. For example:

- In a 1974 case involving the revocation of a permit to use public property, the Supreme Court, while aware of the 1968 precedent, opted to award compensation by "analogically applying" provisions from the National Property Act rather than directly relying on Article 29(3).

- In cases concerning vaccine-related injuries, an initial district court ruling in 1984 cited the 1968 precedent to open a path for compensation, but later Supreme Court decisions in that area became more hesitant about loss compensation as the primary remedy.

- A 2005 Supreme Court decision dealing with long-term city planning restrictions explicitly rejected a direct constitutional claim for compensation in its reasoning for that specific case, leading some commentators to suggest that the judiciary might primarily use the possibility of a direct claim as a tool to uphold the constitutionality of the restrictive laws themselves, rather than as a frequently successful path to actual compensation.

Despite these nuances, the principle established in 1968 remains significant. A 2010 Supreme Court ruling again referenced the 1968 case, affirming that where a financial sacrifice exceeds the bounds of general endurance and imposes a "special sacrifice," the possibility of a compensation claim directly under Article 29(3) of the Constitution remains. Judicial opinions, including supplementary opinions in later cases, have continued to emphasize that courts cannot sidestep the issue of compensation directly under the Constitution if a regulation imposes an unreasonable, uncompensated burden.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's November 27, 1968, ruling in the Rivers Vicinity Land Restriction Ordinance case represents a critical development in Japanese constitutional law. It established that Article 29, Paragraph 3, is more than just an instruction to the legislature; it can be a direct source of a right to claim compensation when an individual endures a "special sacrifice" due to a public welfare regulation that itself lacks specific compensation provisions.

While the bar for proving a "special sacrifice" may be high, and the practical success of such direct claims varied, the decision provides an important constitutional backstop. It ensures that individuals are not left entirely without recourse when they bear a disproportionate and unfair burden for the public good. The ruling allows necessary regulations to function while offering a potential avenue for justice to those who suffer extraordinary losses, affirming the principle that the costs of public benefit should be equitably shared, not unfairly concentrated.