A Child's Right to a Nationality: Japanese Supreme Court on "Parents Unknown" Rule

Date of Judgment: January 27, 1995

Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

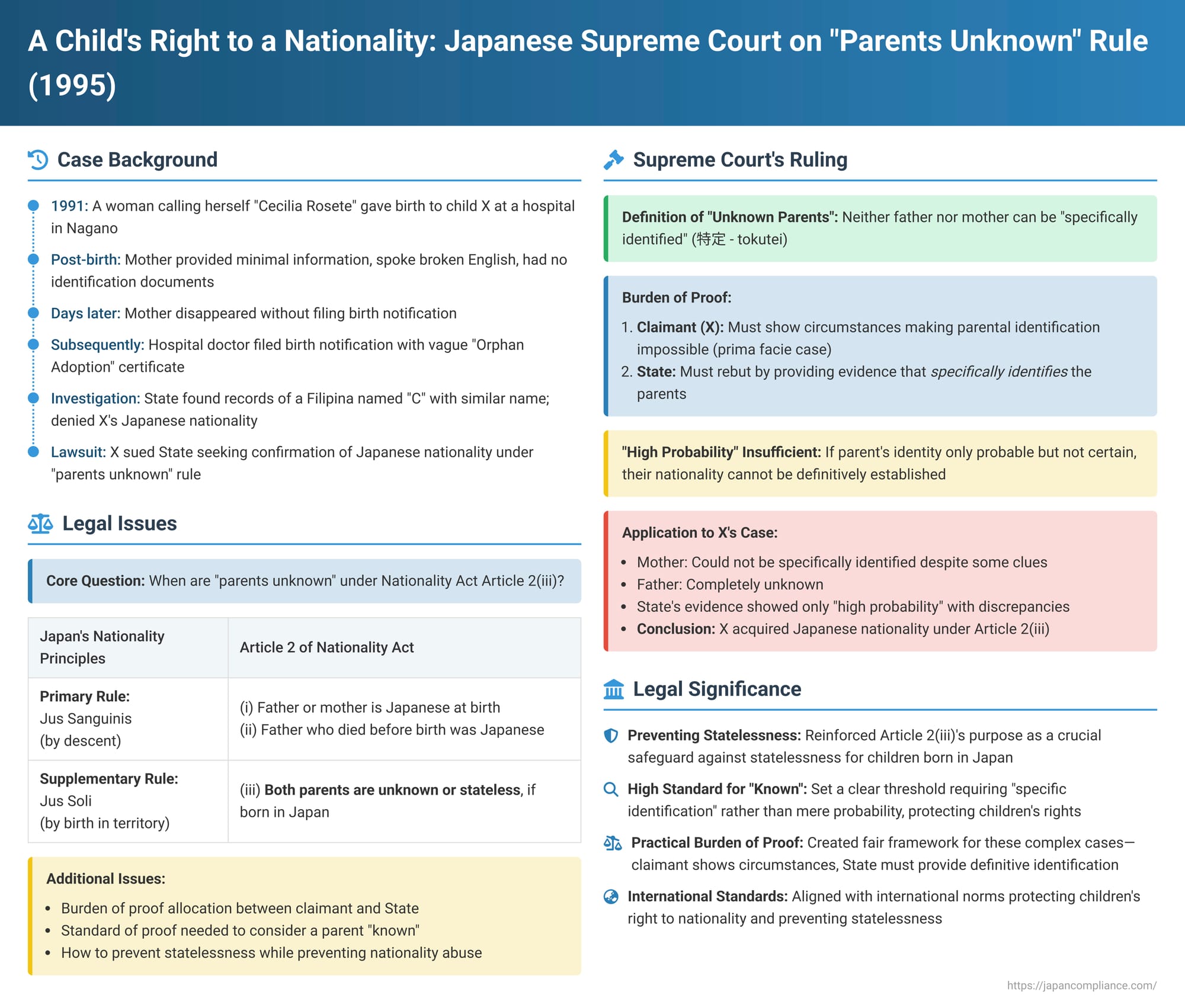

The acquisition of nationality is a fundamental aspect of an individual's legal identity, determining their rights and obligations within a state. Japan's Nationality Act, like that of many countries, primarily follows the principle of jus sanguinis (nationality by descent). However, to prevent statelessness, it also incorporates a supplementary rule of jus soli (nationality by birth in the territory) for children born in Japan under specific circumstances. A key Supreme Court decision on January 27, 1995, provided a crucial interpretation of one such circumstance: when a child is born in Japan and "both parents are unknown."

The Factual Background: A Child Left at a Hospital

The case involved a child, X, whose origins were shrouded in uncertainty:

- In 1991, a woman, who identified herself as "Cecilia Rosete," was admitted to A Hospital in Nagano Prefecture, Japan, and gave birth to X.

- The mother provided minimal verifiable information about herself, communicated primarily through broken English and gestures, and possessed no identification documents like a passport or health insurance card. Some hospital staff and X's eventual adoptive parents had an impression she might be Filipino.

- A few days after X's birth, the mother disappeared without filing a birth notification for X.

- The birth notification for X was subsequently submitted by a doctor from A Hospital. Attached to this notification was a document titled "Orphan Adoption and Immigration Transfer Certificate." This certificate, apparently ghostwritten by a friend who had accompanied the mother, stated that "Ma Cecilia ROSETE" was X's sole parent and that arrangements were being made for X to be adopted by an American pastor couple (who later did become X's adoptive parents).

- No information whatsoever was available regarding X's father.

- The State of Japan (Y) conducted an investigation. It found records of a Filipina national named C (Cecilia Mercado Rosete), who had a birth certificate in City B, Philippines (born to married Filipino parents), and who had entered Japan using a Philippine passport and an entry card. The State concluded that this individual (referred to as D, the person who entered Japan based on C's documents) was likely X's mother. Based on this assumption, the State denied X Japanese nationality.

- X, through legal representatives, filed a lawsuit against the State, seeking confirmation of Japanese nationality. X argued that the State could not definitively identify C (or D) as X's mother, and therefore, X's parents should be considered "both unknown," invoking Article 2, paragraph (iii) of the Nationality Act.

The Tokyo District Court (first instance) ruled in favor of X, finding that X's parents were indeed "unknown" under the Nationality Act. However, the Tokyo High Court reversed this decision. It reasoned that while X had presented circumstances suggesting the parents were unknown, the State had provided counter-evidence indicating a "high probability" that C was the mother. The High Court concluded that X had not met the burden of proving the mother was unknown. X appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Question: When Are Parents Considered "Unknown" for Nationality Purposes?

The central legal issue was the interpretation of the phrase "parents are unknown" as used in Article 2(iii) of the Nationality Act, and how the burden of proving this condition should be allocated between the individual claiming nationality and the State.

Article 2 of the Nationality Act stipulates:

"A child shall be a Japanese national in the following cases:

(i) When, at the time of his/her birth, his/her father or mother is a Japanese national;

(ii) When his/her father who died prior to the birth of the child was a Japanese national at the time of his/her death;

(iii) When both parents are unknown or have no nationality, in a case where the child is born in Japan."

The Supreme Court's Interpretation of "Parents Unknown"

The Supreme Court reversed the High Court's decision and ultimately affirmed X's Japanese nationality. Its reasoning focused on the purpose of Article 2(iii) and the standard of proof required:

1. Purpose of Nationality Act Article 2(iii): Preventing Statelessness

The Court began by emphasizing that the primary mode of acquiring Japanese nationality is by descent (jus sanguinis), as laid out in Article 2(i) and (ii). Article 2(iii) serves as a supplementary rule based on birth in the territory (jus soli) designed to prevent statelessness (無国籍者の発生防止 - mukokusekisha no hassei bōshi). If nationality depended solely on parents' nationality, children born in Japan whose parents were unknown or themselves stateless might be left without any nationality. The provision aims to grant Japanese nationality to such children born in Japan.

2. Meaning of "Parents are Unknown":

Flowing from this purpose, the Supreme Court interpreted "parents are unknown" to mean that neither the father nor the mother can be specifically identified (特定 - tokutei).

- Even if there is a "high probability" that a certain individual might be the parent, this is insufficient to consider that parent "known" for the purposes of Article 2(iii) if their identity cannot be definitively established.

- The rationale is straightforward: if a parent's identity (and crucially, their nationality) is only probable but not certain, it's impossible to determine the child's nationality based on that parent's status under the primary jus sanguinis rules. Only when a parent is specifically identified can their nationality be ascertained and applied to the child.

3. Burden and Standard of Proof:

The Supreme Court clarified the allocation and standard of proof:

- The person claiming Japanese nationality (X) bears the initial burden of proving the existence of facts that fall under the "parents are unknown" requirement. This can be met by demonstrating circumstances surrounding their birth which, according to common societal understanding, make it impossible to specifically identify who their father and mother are. Such evidence establishes a prima facie case that the parents are unknown.

- If the State (Y) contests this, it must then provide counter-evidence. However, merely presenting evidence that suggests a "high probability" that a certain person is a parent is not enough to overturn the prima facie finding if that counter-evidence still falls short of specifically and definitively identifying that person as the parent.

Application to X's Case:

- X's Mother: The woman who gave birth to X had used a name, but provided no verifiable identification and her stated birth year had a five-year discrepancy with the person (C) the State suspected her to be. She disappeared soon after X's birth. These circumstances clearly made it impossible to specifically identify her from X's perspective.

- The Father: There were no clues whatsoever regarding X's father.

- State's Counter-Evidence: The State's investigation pointed to a possibility that X's mother was a specific Filipina national (C), based on some similarities in name and birth month/day found in immigration records and Philippine documents. However, the Supreme Court noted significant discrepancies:

- The five-year difference in birth year.

- Different spellings of the name "Cecilia Rosete" across various documents.

- The fact that individual C had apparently entered Japan about three years before X's mother's hospitalization, yet X's mother communicated only with broken English and gestures (suggesting limited time or integration in Japan, or a different person altogether).

- Supreme Court's Conclusion on Facts: The High Court itself had only gone as far as to say there was a "high probability" that C was the mother, not a definitive identification. The Supreme Court found that the State's evidence, with its inconsistencies, was insufficient to specifically identify X's mother and thus failed to rebut the prima facie case that X's mother was "unknown."

- Final Determination: Since X was born in Japan, the father was entirely unknown, and the mother could not be specifically identified, X qualified under Article 2(iii) of the Nationality Act as a child whose parents were both unknown. Therefore, X was deemed to have acquired Japanese nationality at birth.

Significance and Commentary Insights

This 1995 Supreme Court decision has several important implications:

- Reinforcing the Goal of Preventing Statelessness: The ruling robustly upholds the primary purpose of Article 2(iii) of the Nationality Act, interpreting its conditions in a way that favors the granting of nationality to children born in Japan who might otherwise be stateless.

- Clarifying the "Unknown" Standard: By requiring "specific identification" of a parent for them to be considered "known," the Supreme Court set a relatively high bar for the State to overcome a prima facie case of unknown parentage. This means authorities cannot deny nationality under this provision based on mere speculation or inconclusive evidence regarding parental identity.

- Burden of Proof Allocation: The Court's approach to the burden of proof—requiring the claimant to establish initial circumstances pointing to unknown parentage, and then requiring the State to provide definitive identifying evidence in rebuttal—provides a practical and fair framework for these difficult cases. Professor Yamamoto's commentary notes that this reflects the interpretation of the substantive requirement ("unknown") onto the standard of proof itself.

- Focus on Ascertainable Nationality for Jus Sanguinis: The decision implicitly underscores that for the primary jus sanguinis rules to apply, the nationality of at least one parent must be ascertainable. If parental identity, and by extension their nationality, is unclear, the supplementary jus soli provision of Article 2(iii) comes into play to prevent statelessness.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1995 ruling in this nationality confirmation case is a significant interpretation of a crucial provision within Japan's Nationality Act. By emphasizing the need for "specific identification" before a parent can be considered "known" for the purposes of Article 2(iii), and by carefully allocating the burden of proof, the Court provided vital protection against statelessness for children born in Japan under circumstances of uncertain parentage. The decision reflects a humane approach, prioritizing the child's right to a nationality when their connection to a specific foreign nationality through their parents cannot be definitively established.