A Child's "Mistake": How a 1964 Japan Supreme Court Ruling Redefined Negligence for Young Victims

Date of Judgment: June 24, 1964

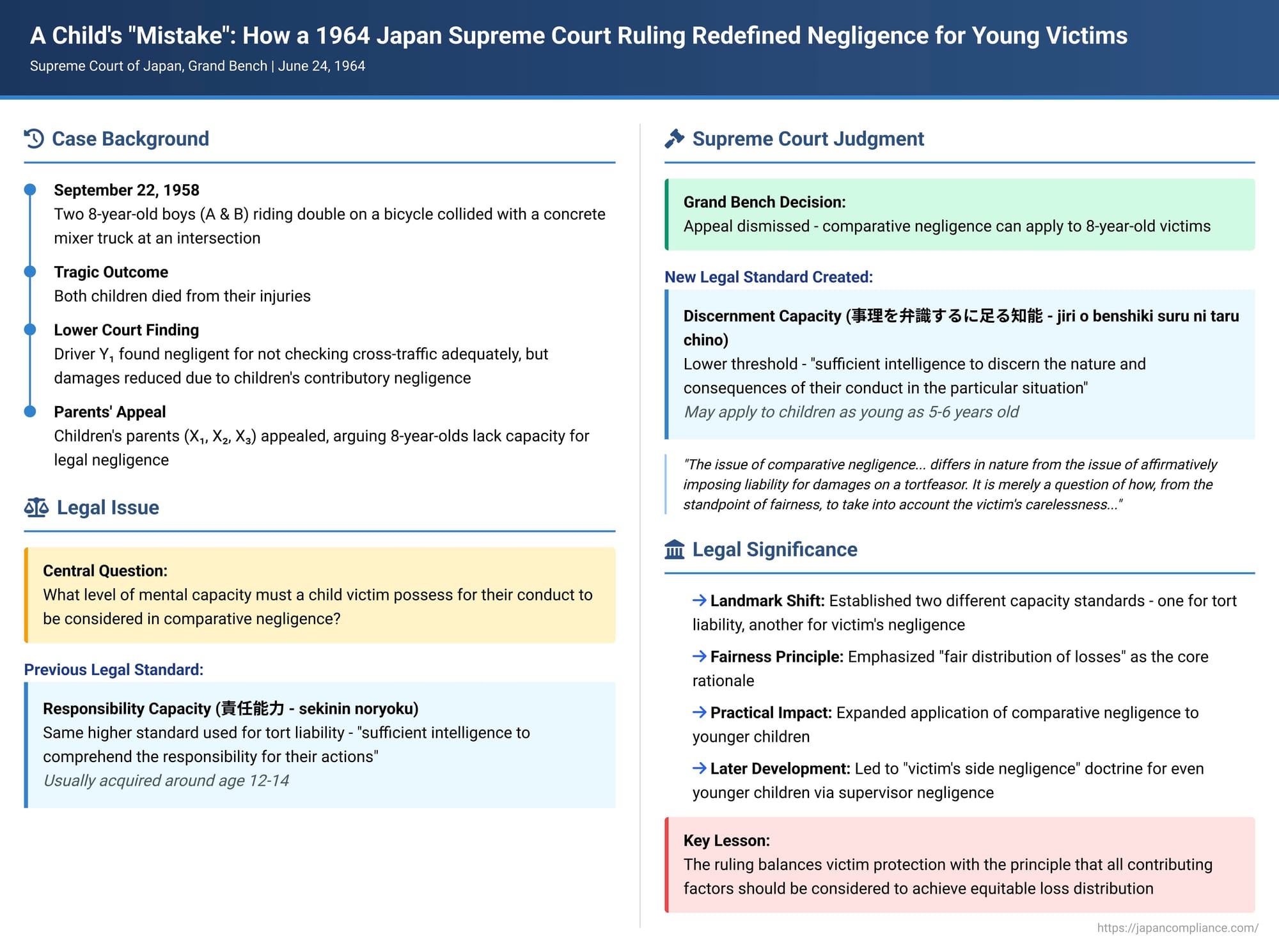

When an accident occurs, the concept of comparative negligence (or contributory negligence) plays a crucial role in determining how damages are allocated. This legal principle acknowledges that a victim's own actions might have contributed to their injuries, and if so, their compensation may be reduced accordingly. But what happens when the victim is a child? What level of understanding, maturity, or foresight must a child possess for their conduct to be considered "negligent" in the eyes of the law? This profound question was addressed by the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan in a landmark decision on June 24, 1964, a ruling that reshaped the understanding of a child victim's accountability for their own harm.

The Tragic Accident and the Legal Impasse

The case (Supreme Court, Grand Bench, Showa 36 (O) No. 412) stemmed from a devastating road accident that occurred around 4:00 PM on September 22, 1958. The incident took place at a crossroads with good visibility but considerable traffic. Y₁, an employee of Company Y₂ (a ready-mixed concrete business), was driving a concrete mixer truck. He entered the intersection, heading west at approximately 25 km/h.

At the same time, two young boys, A (8 years and 2 months old) and B (8 years and 1 month old), both second-grade elementary school students, were riding double on a children's bicycle, proceeding south into the same intersection. Their bicycle collided with the right rear side of Y₁'s truck, and tragically, both A and B died from their injuries.

In the ensuing lawsuit, the parents of A (X₁ and X₂) and the mother of B (X₃) sought damages from Y₁ and Company Y₂ (under employer liability principles). The claims included lost future earnings for the deceased children (which the parents inherited), funeral expenses, and solatium for their own grief.

The lower court found Y₁ negligent for failing to sufficiently check for cross-traffic and for maintaining his speed through the intersection. However, the court also determined that the children, A and B, were contributorily negligent. Their negligence consisted of not paying adequate attention to Y₁'s truck and attempting to cross the intersection while riding double on a single bicycle. Based on this finding of contributory negligence, the lower court significantly reduced the amount of damages awarded to the parents. For example, the court calculated the children's total lost earnings at over 2.47 million yen but reduced the final compensation attributed to these damages to 1 million yen after factoring in their negligence.

The parents appealed to the Supreme Court. Their primary argument was that the lower court had erred in applying the doctrine of comparative negligence to children as young as A and B. They contended that children of that age lack the requisite mental capacity for their actions to be legally deemed "negligent," and that this interpretation misconstrued Article 722, paragraph 2 of the Civil Code (which governs comparative negligence). They also pointed out that this contradicted a prior Supreme Court precedent (a 1956 judgment) that had denied the application of comparative negligence to an 8-year-and-10-month-old child.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision: A Shift in Perspective

The Grand Bench of the Supreme Court, in its ruling on June 24, 1964, dismissed the parents' appeal, thereby upholding the lower court's decision to apply comparative negligence. However, in doing so, the Court fundamentally altered the existing legal standard for assessing the negligence of child victims.

The Old Rule: "Responsibility Capacity" as the Benchmark

Prior to this 1964 decision, Japanese case law and prevailing legal theory held that for a victim's actions to be considered in comparative negligence, the victim needed to possess "responsibility capacity" (責任能力 - sekinin noryoku). This is the same level of mental capacity required under Article 712 of the Civil Code for a person to be held liable for harm they inflict on others through a tortious act. Essentially, it refers to the "sufficient intelligence to comprehend the responsibility for their actions" (その行為の責任を弁識するに足る知能 - sono koi no sekinin o benshiki suru ni taru chino). The rationale was that if a child lacked the capacity to be held responsible for causing harm, they should similarly be shielded from having their own compensation reduced due to their actions when they were the victim.

The New Standard: "Discernment Capacity" for Victim Negligence

The Grand Bench explicitly decided to change this established precedent. The Court drew a crucial distinction between the capacity needed to impose tort liability on someone and the capacity relevant to assessing a victim's contribution to their own harm for purposes of comparative negligence.

The Court reasoned:

"However, the issue of comparative negligence under Article 722, paragraph 2 of the Civil Code differs in nature from the issue of affirmatively imposing liability for damages on a tortfeasor. It is merely a question of how, from the standpoint of fairness, to take into account the victim's carelessness concerning the occurrence of the damage when determining the amount of damages for which the tortfeasor should be liable."

Based on this distinction, the Court established a new, less stringent standard for child victims:

"Therefore, when considering the negligence of a minor victim, it is sufficient if the minor possesses enough intelligence to discern the nature and consequences of their conduct in the particular situation (事理を弁識するに足る知能 - jiri o benshiki suru ni taru chino); it is not necessary, as in the case of imposing tort liability on a minor, that they possess the intelligence to comprehend the responsibility for their actions."

This "discernment capacity" (jiri o benshiki suru ni taru chino) refers to a more basic level of understanding – the ability to recognize that certain actions might lead to danger or harm, particularly to oneself, in a given context. It does not require an understanding of the broader legal or social implications of one's actions, which is part of "responsibility capacity."

Application to the 8-Year-Old Victims in the Case

Applying this new standard, the Supreme Court considered the facts related to A and B. They were over eight years old, described as ordinary healthy boys, and were already in their second year of elementary school. The Court noted the lower court's finding that they had been "sufficiently warned about traffic dangers at school and home, and had an understanding of traffic dangers". Based on these circumstances, the Supreme Court concluded that A and B possessed "sufficient intelligence to discern the nature and consequences of their conduct" (jiri o benshiki suru ni taru chino) in the situation that led to the accident.

Therefore, the lower court's decision to find them contributorily negligent for riding double and not paying sufficient attention, and consequently to reduce their damages, was deemed appropriate and upheld.

Unpacking "Discernment Capacity" vs. "Responsibility Capacity"

The distinction between these two levels of mental capacity is vital:

- Responsibility Capacity (for tort liability): This is the higher threshold, generally associated with the ability to understand the legal and social wrongfulness of one's actions if they cause harm to others. While not a fixed age, Japanese law typically considers children to acquire this around 12-14 years old, though it's assessed on a case-by-case basis.

- Discernment Capacity (for victim's comparative negligence, post-1964 ruling): This is a lower threshold. It pertains to a child's ability to understand the factual nature of their actions and the immediate risks of danger or harm those actions might pose, particularly to themselves. The 1964 ruling indicated that 8-year-olds could possess this capacity, and subsequent case law has suggested it might be found in children as young as 5 or 6 years old, depending on the specific circumstances and the child's individual development.

The Rationale: Fairness in Loss Allocation

The driving force behind this significant change in legal doctrine was the principle of "fairness" (公平の見地 - kohei no kenchi) in the allocation of loss. The Grand Bench felt that if a victim, even a child, possessed a basic understanding of the risks involved in their conduct and their actions contributed to the occurrence or severity of their own injuries, it was equitable to take this into account when determining the extent of the tortfeasor's liability. The focus shifted from a rigid application of the tort liability capacity standard to a more nuanced assessment aimed at achieving a just distribution of the financial burden arising from the accident.

Evolution of Legal Thought and Subsequent Developments

This 1964 Grand Bench decision was a product of evolving legal thought. During the 1950s and 1960s, a period marked by a rapid increase in traffic accidents in Japan, legal scholars began to advocate for a broader application of comparative negligence, often arguing for a relaxation of the capacity requirements for victims. The adoption of the "discernment capacity" standard by the Supreme Court was a significant step in this direction.

Further developments in Japanese law have continued this trend. Notably, the concept of "victim's side negligence" (被害者側の過失論 - higaisha-gawa no kashitsu ron) gained prominence. This allows courts to consider the negligence of a very young child's supervisors (such as parents or guardians) if the child victim themself lacks even discernment capacity. For example, if an infant, incapable of discerning danger, darts into the road due to a lapse in parental supervision, the supervisor's negligence can be factored into the comparative negligence calculation.

The practical effect of these combined developments (the lowered "discernment capacity" standard for the child victim and the "victim's side negligence" for those even younger or less capable) is that it has become more likely that some conduct attributable to the victim's sphere will be considered in the overall assessment of damages. This reflects a broader judicial inclination towards a comprehensive evaluation of all contributing factors to ensure a fair distribution of loss.

Ongoing Academic Discussion

The 1964 ruling, while settling the immediate legal standard, spurred further academic debate. Some legal scholars argue for eliminating any subjective capacity requirement for victim negligence altogether. They propose that a child's conduct should be assessed objectively: if the action was externally "careless" by general standards and causally contributed to the harm, it should be considered in comparative negligence, regardless of the child's individual understanding. This view often emphasizes that comparative negligence is primarily about the fair allocation of losses rather than about blaming the victim.

Conversely, other scholars actively defend the "discernment capacity" requirement. They maintain that for comparative negligence to be justly applied, the victim must have had at least a basic ability to recognize the risk and a corresponding expectation that they could have acted to avoid it. From this perspective, "discernment capacity" is a necessary minimum to ensure that the victim is not unduly penalized for conduct they could not reasonably have understood as dangerous. These discussions touch upon fundamental theories about the very nature and purpose of the comparative negligence doctrine – whether it is primarily fault-based or serves as a mechanism for equitable risk distribution. The differing views also have implications for how far the principle of comparative negligence should extend, for example, to cases involving a victim's pre-existing physical or mental vulnerabilities.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Fairness and Pragmatism

The Supreme Court's Grand Bench decision of June 24, 1964, stands as a pivotal moment in the evolution of Japanese tort law. By distinguishing the capacity needed for a child victim's actions to be considered in comparative negligence from the higher capacity required for tort liability, the Court instituted a more pragmatic and, in its view, fairer approach. The introduction of the "discernment capacity" standard lowered the threshold, allowing for a more nuanced consideration of a child's contribution to their own injury, provided they had a basic understanding of the situational risks.

This ruling underscored the judiciary's commitment to fairness in damage allocation, ensuring that while tortfeasors are held accountable, the shared responsibility for an incident, where it exists, is appropriately reflected in the final award. The "discernment capacity" standard continues to be a central element in how Japanese courts navigate the sensitive and complex issue of negligence involving minor victims, striving to balance protection with a realistic assessment of a child's developing ability to understand and react to the world around them.