A Child in Limbo: Japan's Supreme Court on Resident Records for Children with Unfiled Birth Notifications

A Second Petty Bench Ruling from April 17, 2009

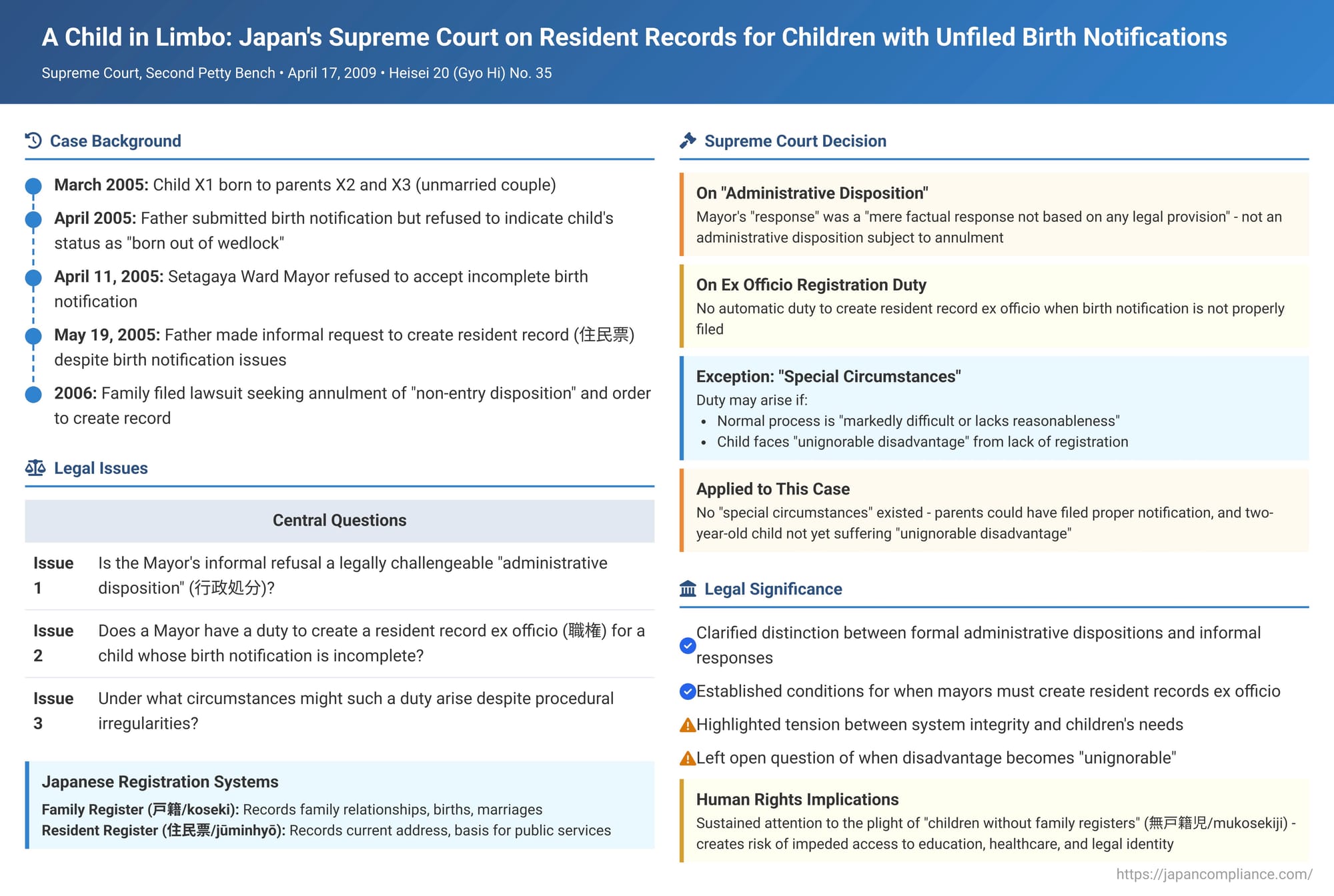

Official registration of birth and residency is fundamental to an individual's legal identity, serving as the gateway to a multitude of rights, benefits, and civic participation. In Japan, these records are managed through two primary interconnected systems: the family register (koseki) and the resident register (jūminhyō). A 2009 Supreme Court decision by its Second Petty Bench (Heisei 20 (Gyo Hi) No. 35) addressed a poignant situation where a child was left without a resident record due to a principled stand taken by the parents regarding the birth notification process. The case examined whether a municipal mayor's informal refusal to create a resident record under such circumstances could be legally challenged as an "administrative disposition," and it explored the conditions under which a mayor might have a positive duty to register a child ex officio.

The Facts: A Principled Standoff

The case involved X1, a child born in March 2005 to X2 (mother) and X3 (father). The parents were in a de facto marital relationship, meaning they lived together as a family but had not formally registered their marriage. This status had implications for the information required on X1's birth notification form (出生届 - shusshō todoke).

When X3, the father, went to submit the birth notification for X1 to the Setagaya Ward Mayor in Tokyo, he intentionally left blank the field on the form that required designating the child's relationship to the parents—specifically, whether the child was "legitimate" (嫡出子 - chakushutsushi) or a "child born out of wedlock" (嫡出でない子 - chakushutsu de nai ko). The parents considered the latter term discriminatory and objected to its use. The Ward Mayor requested X3 to complete this section as required by law, but X3 refused. The Mayor even proposed an internal administrative workaround, sometimes referred to as "post-it note processing" (付せん処理 - fusen shori), where the ward office would internally note the child's status based on other submitted documents while potentially leaving the contested field on the main form as presented by the parents. However, this compromise was also rejected by the parents. Consequently, on April 11, 2005, the Ward Mayor issued a formal decision not to accept (不受理処分 - fujuri shobun) the birth notification due to these deficiencies. The legality of this non-acceptance of the birth notification was later upheld by the Supreme Court in separate family court proceedings.

Following this, on May 19, 2005, X3 made an informal request (申出 - mōshide) to the Ward Mayor, invoking Article 8 of the Basic Resident Register Act (住民基本台帳法 - Jūmin Kihon Daichō Hō, hereinafter "the Act" or "BRRA"). He asked the Mayor to create a resident record (jūminhyō) for X1. The Mayor responded that a resident record would not be created for X1 because a valid birth notification had not been formally submitted and accepted. This specific refusal to act on the informal request is referred to as "the present response" (本件応答 - honken ōtō) in the judgment. Despite repeated similar requests from the parents, the Mayor's stance did not change.

The Legal Battle: Is a "Response" a Challengeable "Disposition"? Duty to Register?

Viewing the Mayor's ongoing refusal to create a resident record as a "disposition of non-entry," X1 (represented by his parents) and the parents themselves (X2 and X3) eventually filed a lawsuit in June 2006 against Setagaya Ward (Y, the defendant/appellee). This followed the exhaustion of available administrative appeal procedures. Their lawsuit sought:

- The annulment of the Mayor's "non-entry disposition" (i.e., the refusal to create the resident record).

- A court order compelling the Ward Mayor to create the resident record for X1 (a type of mandamus action not reliant on a prior formal application, known as a 非申請型義務付け訴訟 - hi-shinseigata gimuzuke soshō).

- State compensation for damages allegedly suffered due to the lack of a resident record.

The Tokyo District Court, as the court of first instance, recognized legal standing only for the child, X1. It found that the Mayor had a duty to create the resident record for X1, treated the Mayor's "response" as an administrative disposition subject to annulment, annulled it, and ordered the creation of the record. The claim for monetary damages was denied.

The Tokyo High Court, acting as the appellate court, overturned the District Court's ruling regarding the annulment and the order to create the record. It dismissed X1's annulment claim and quashed the order compelling the creation of the record, while upholding the denial of the compensation claim. The plaintiffs then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision of April 17, 2009

The Supreme Court's Second Petty Bench largely sided with Setagaya Ward, although its reasoning on some points differed from that of the High Court. Ultimately, it dismissed the plaintiffs' claims concerning the creation of the resident record.

1. The Mayor's "Response" Was Not an "Administrative Disposition":

The Court first addressed the legal nature of the Mayor's refusal to create a resident record following X3's informal request.

- It distinguished X3's informal request from a formal notification (like a birth notification) made under the Act, which would impose a legal duty on the Mayor to respond in a certain way (as indicated in Article 11 of the Basic Resident Register Act Enforcement Order).

- The Court characterized X3's request as merely an informal urging for the Mayor to exercise his discretionary power under Article 14, paragraph 2 of the Act. This provision allows a mayor to investigate and correct the resident register ex officio (職権 - shokken) if there appears to be an error or omission.

- Therefore, the Mayor's "response" – stating that a record would not be created at that point – was deemed a "mere factual response not based on any legal provision" (法令に根拠のない事実上の応答にすぎず - hōrei ni konkyo no nai jijitsujō no ōtō ni sugi zu).

- As such, this "response" did not directly create, alter, or confirm the legal rights, duties, or legal status of X1 or X3. Consequently, it did not qualify as an "administrative disposition" (行政処分 - gyōsei shobun) that could be the subject of an annulment action under the Administrative Case Litigation Act. On this basis, the Supreme Court concluded that X1's annulment claim was inadmissible from the outset and should be dismissed. The legal commentary notes that this finding, focusing on the nature of the citizen's request rather than solely on the impact of the administration's response, was a departure from the lower courts' approach.

2. No Automatic Duty for Ex Officio Resident Record Creation in This Specific Case:

The Court then considered whether, independently of the parents' flawed requests, the Mayor had a general legal duty to create a resident record for X1 ex officio.

- General Principle: The Court stated that when a birth notification for a child (who is intended to be entered into the father's or mother's family register, or koseki) is not submitted, and as a result, no resident record (jūminhyō) is created, the municipal mayor is not always obligated to create a resident record through their own ex officio investigation (職権調査 - shokken chōsa). The primary and principled approach, according to the Court, is for the mayor to urge the person(s) responsible for submitting the birth notification to do so correctly. Once the birth is duly recorded in the family register system, the resident register is then typically created or updated based on that information. The Act generally does not envision ex officio creation of a resident record as the primary method in such situations, reserving it for specific exceptions such as foundlings or individuals with no clear family register.

- Exceptional Circumstances Triggering an Ex Officio Duty: However, the Court acknowledged that this general rule is not absolute. An obligation for the mayor to create a resident record for a child through ex officio investigation may arise if using the ordinary method (i.e., urging and awaiting a proper birth notification) "is markedly difficult or lacks reasonableness in light of social common sense, or other special circumstances exist" (その方法によって住民票の記載をすることが社会通念に照らし著しく困難であり又は相当性を欠くなどの特段の事情がある - sono hōhō ni yotte jūminhyō no kisai o suru koto ga shakai tsūnen ni terashi ichijirushiku konnan de ari matawa sōtōsei o kaku nado no tokudan no jijō ga aru).

3. Application of the Exception to X1's Case:

The Supreme Court then examined whether such "special circumstances" existed in X1's situation:

- The Court noted that X1's fundamental identity details, including his relationship to his parents, were clear from other available information (e.g., the father had filed a fetal acknowledgment which had been accepted, and the birth certificate accompanying the initially submitted birth notification was presumably in order, apart from the contested field). It acknowledged that creating a resident record for X1 as a member of X2's (the mother's) household would not have contradicted the purpose of the Basic Resident Register Act and might even have simplified administrative processing for the Ward.

- However, the Court found that the primary reason the Mayor had not taken such ex officio action was the parents' ongoing failure to file a legally proper birth notification. The Court characterized this failure as stemming from their "adherence to their own beliefs" regarding the "child born out of wedlock" designation. It emphasized that there was no particular objective impediment preventing them from filing a corrected notification, especially since the Mayor had offered a procedural compromise (the "post-it note" method) and the non-acceptance of their initial flawed birth notification had been judicially confirmed as lawful. Therefore, the Court concluded that the parents' failure to file a proper birth notification lacked "unavoidable reasonable grounds," meaning the first type of "special circumstance" (insurmountable difficulty in filing) did not exist.

- The Court then considered the second type of special circumstance: whether the lack of a resident record was causing X1 "unignorable disadvantage" (看過し難い不利益 - kanka shi gatai furieki). If such severe disadvantage existed, the Mayor might be obligated to create the record ex officio, even if the parents' neglect to file was without compelling reason.

- The Court identified the "greatest disadvantage" of not having a resident record as the inability to be registered on the electoral roll. However, since X1 was only two years old at the time of the High Court hearing, this disadvantage had "not yet actualized".

- Regarding other administrative services (such as healthcare, education, etc.), Setagaya Ward had indicated that it generally provided these services even to residents not formally on the register, although the procedures might be "more cumbersome".

- The Supreme Court found no evidence in the record that X1 was currently suffering from unignorable disadvantage due to the lack of a resident record.

Conclusion on the Legality of the Mayor's Inaction:

Based on this analysis, the Supreme Court concluded that the Setagaya Ward Mayor's decision not to create a resident record for X1 ex officio, under the specific circumstances presented, was not a violation of the Basic Resident Register Act (specifically citing Articles 8 and Enforcement Order Article 12, paragraph 3). Consequently, the plaintiffs' claim for state compensation based on the alleged illegality of this inaction also failed.

Understanding Key Japanese Legal Concepts

This case touches upon several fundamental concepts in Japanese administrative law:

- Administrative Disposition (行政処分 - gyōsei shobun): This is a formal act by an administrative agency that directly affects the legal rights or duties of specific individuals or entities, making it subject to direct judicial challenge via an annulment lawsuit. The Supreme Court found that the Mayor's informal "response" to an informal request did not meet this definition.

- Ex Officio Powers (職権 - shokken): This refers to the authority of public officials or administrative bodies to take action on their own initiative, without a formal application from a citizen, often to ensure the accuracy of public records or to enforce legal compliance. The Basic Resident Register Act does grant mayors some ex officio powers to maintain the register.

- Family Register (koseki) and Resident Register (jūminhyō): Japan employs two main systems for official personal registration. The koseki is a family-based system that records vital events like births, deaths, marriages, and familial relationships, including parent-child lineage. The jūminhyō, on the other hand, is an individual-based resident registration system that records a person's current address and household composition. The jūminhyō serves as the foundational public record for a wide array of administrative services, including electoral registration, schooling, national health insurance, and pensions. Ordinarily, information from an accepted birth notification flows first into the koseki, and the jūminhyō is then created or updated based on the information from the koseki and other notifications (like moving notifications). This interconnected system is designed to ensure accuracy, prevent inconsistencies (like double registration or omissions), deter identity fraud, and simplify administrative procedures for residents. This case starkly illustrates the difficulties that arise when this standard procedural flow is disrupted at the initial birth notification stage.

The "Unignorable Disadvantage" Standard and Its Implications

The Supreme Court's articulation of "special circumstances" that could trigger an ex officio duty for a mayor to create a resident record—specifically, when awaiting a proper birth notification is "markedly difficult or lacks reasonableness," or when the child faces "unignorable disadvantage"—is a notable development.

- This standard acknowledges that the state has a residual responsibility towards children even when parental actions (or inactions) create administrative hurdles.

- However, applying the "unignorable disadvantage" test presents its own challenges. As legal commentary points out, determining at what precise point a potential future disadvantage (like the inability to vote for a two-year-old) becomes sufficiently "realized" or "unignorable" to trigger a present legal duty on the part of the administration can be difficult and may lead to ongoing uncertainty.

Critical Perspectives and Broader Human Rights Concerns

This judgment, while clarifying certain aspects of administrative procedure, has also drawn critical commentary, particularly concerning the welfare of "children without a family register" (mukosekiji).

- Nature of the "Response": Some legal scholars have argued that the Mayor's clear and repeated refusal to register X1, effectively stating that no resident record would be forthcoming until a "correct" birth notification was filed, should have been considered a de facto administrative disposition given its significant and definitive impact on X1's legal status and the parents' ability to secure his registration. The commentary suggests that such a response could be seen as an ultimatum carrying substantial psychological pressure, leading to tangible "factual disadvantages".

- Child's Rights vs. Parental Stance: The case highlights a difficult tension between respecting the deeply held beliefs of parents and ensuring a child's fundamental right to legal recognition, a name, and access to essential public services. Critics argue that the child's interests might have been insufficiently prioritized when balanced against the parents' continued refusal to comply with the formal requirements of the birth notification system, even after administrative compromises were offered and the initial non-acceptance was judicially upheld.

- Plight of Mukosekiji: The situation of children without a family register entry (and often, consequently, without a resident record) is a serious social issue in Japan, as it can impede access to education, healthcare, and other fundamental rights. The commentary points out that even prior to this ruling, administrative practice did not entirely forbid the ex officio registration of such children in all circumstances. The Supreme Court's criteria for when an ex officio duty arises are therefore important, but their application may continue to be debated, especially concerning what constitutes "unignorable disadvantage" for a young child who lacks even a legally registered name, a matter directly implicating personal dignity and human rights.

Significance of the Ruling

The 2009 Supreme Court decision in the Setagaya Ward resident register case provides important, albeit nuanced, guidance on several fronts:

- It clarified the generally non-reviewable nature of informal administrative responses as "administrative dispositions," directing challenges towards more formal and legally defined administrative acts.

- It established (or at least significantly elaborated upon) the specific conditions under which a municipal mayor might have a positive legal duty to exercise ex officio powers to create a resident record for a child whose birth notification has not been duly accepted by the authorities.

- The ruling underscored the intended procedural linkage between Japan's family registration system (initiated by birth notification) and its resident registration system, while also grappling with the consequences when this linkage breaks down due to parental actions based on personal conviction.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment in this case navigates a complex terrain involving parental choices, the integrity of official registration systems, and a child's fundamental need for legal recognition. While ultimately finding the Setagaya Ward Mayor's inaction lawful under the specific and rather unique circumstances of the parents' persistent refusal to file a formally compliant birth notification (despite offers of administrative accommodation), the Court did acknowledge that a duty to act ex officio could arise in exceptional situations involving extreme difficulty for parents or unignorable disadvantage to the child. The decision highlights the significant challenges faced by "children without a family register" and underscores the critical role of official registration systems in enabling individuals to fully participate in society and access their rights. It serves as a somber reminder of the profound impact that administrative procedures and parental decisions can have on a child's legal and social existence.